Articles/Essays – Volume 41, No. 3

Who Brought Forth This Christmas Demon

Tim’s wife left him with three dozen blue spruce still trussed up on the truck and better than fifty juniper, Scotch, red cedar, and Douglas on the lot. She left him when he was finishing up a sale with a stunning customer. He remembered this—and he had a photo of her foot on his phone to remind him. The thing was, this gorgeous woman, with flaxen-honey hair, green eyes, perfect cheeks, and a white-teeth smile that singed the needles of the junipers next to her, smelled like unholy hell: some foreign and eccentric perfume. She was no doubt a beautiful woman, but she smelled like a fancy toilet bowl tablet. His eyes were watering, and he was about to sneeze as the lady handed over a crisp fifty for the nine-foot Scotch that she said would fit nicely in the home’s great room.

That’s when his cell phone rang. It was Karri. His wife.

And Tim had asked Karri to hold on just a minute. And then he had asked this perfect, yet fetid, customer if she wouldn’t mind holding the phone. Just hold it for the moment it would take him to hoist the perfect tree into the immaculate bed of her big Dodge truck. And after he’d done that, the smelly goddess had handed the phone (along with the freshly snapped photo of her foot) back to him with a smile because he had given her a deal on the tree—not that she needed a deal. And off she went to the doubtless warmth and love of her home, her husband, two blessedly ideal daughters, and the spayed purebred chocolate Labrador. And then Karri from down deep inside the electronics and mystery of the little phone pressed against his ear said she didn’t love him anymore. Told him she was tired of his silly business ventures and waiting to have his children. She was leaving. Today. She had the cat and all she needed. And that was that. And there he was, dead phone, alone, and the chemical stench of that beautiful woman lingering in the still air of winter.

***

It wasn’t until early May that the city letters regarding the trees started to get ugly. Tim had an acquaintance—poker buddy—on the Payson City Council who had pulled strings with ordinances and covered up non-actions for as long as he could. But when it came right down to it, it was bare-naked obvious: Right there in the middle of town there were Christmas trees for sale—in May.

Tim had leased the old parking lot at the defunct Safeway from a businessman in Provo. The man was out of reach due to an extended vacation in Guatemala, and the city had no recourse but to go after the lessee. And in fairness, the city had taken its time about it. It had been a wet winter and spring, and all the merchandise in its fading cheer had weathered it fairly well up until the end of April when someone had reported a rat scurrying in and around the tired trees. And please, in such close proximity to the public library and the Flying Wheel pizzeria across the street. There was no other course of action. The trees had to be removed.

It was a Thursday. Tim got out of bed and poured himself a crystal tumbler of bourbon and water. It was bottom-shelf bourbon and it was early, nearly noon. He could do nothing about the hour; it was what it was. And the economical bourbon? Well, it was alcohol. His once comfortable savings were nearing closure, and of necessity he had to make concessions somewhere.

Tim ventured out to the mailbox in his “T” monogrammed robe, gathered his mail, and retreated back to the house. He read the final letter from the city, used the envelope as a coaster. The Payson city fathers had given him until the day after tomorrow to remove all the merchandise from the lot or they would do it and it wouldn’t come cheap.

In truth, the trees were not a priority for Tim. There was the high def TV. There was his belly, becoming quite illustrious and swollen. And there were his cigars.

By the end of February, he had burned through all the lovingly preserved premium hand-mades in his humidor—even the box of Cubans he’d smuggled up from Cancun. And as much as it had torn at his hubris lining, he had walked right into the nearest convenience store and bought up twelve packages of the biggest Swisher Sweets they carried. At home in the den he dumped them into the cedar-lined humidor Karri had given him two Valentine’s Days ago. He had checked the humidity, added some distilled water to the water pillow, and, praying for a Havana miracle, had closed the lid.

And so Tim lit one now, right there in the kitchen. Like he had lit one of the Cubans up on a Saturday last summer after lunch. Karri had taken the broom up at him then and swept him out onto the deck into the sunlight. It was funny. Then.

He took a long draw on the miserable cigar there at the table and flicked open his cell phone and scrolled to the photo of the woman’s foot. It was clad in a black Mary Jane shoe of sorts with a tiny buckle over the top. The parking lot pavement was slushy-gray and the buckle shone like a diamond. Tim looked at the photo of the woman’s foot ten, twenty times a day. He knew this snapshot captured the very minute everything fell apart for him. It was the proverbial foot put-down.

Tim licked all along the sweetened cheap cigar until the sugar was gone. And then he dunked the head into his bourbon and sucked on that. He smelled bad. His eyes hurt. His private areas were dank and musty from overuse and under-cleansing. He finished his cigar and took a shower.

He got out of the steaming water and quaffed back his tumbler of bourbon. Then he shaved. When he was done, he looked in the mirror and saw a stranger. He saw a man from six months before. A man who risked stability in pursuit of riches in ways he thought were calculated. He saw a man who did not realize then what that risk truly was.

He lifted his eyebrow to the clean visitor in the mirror, gave him a very inquisitive observation. This was not the person he’d come to know and scorn over the course of the last four months. This person might just pick up the phone and call his wife. He might take that risk. Tim was curious to know what the old stranger in the mirror would accomplish on this day.

What he accomplished was measured out in exactly 4,707 calories, 2.2 hours of web-surfing, 12 flat hours of television, and three hours of staring at the walls waiting for fate to smolder, lick the edges of his being, and combust.

Tim had last heard from Karri on March 7. She’d called him from her mother’s in St. George.

“What ya doin?” she’d asked him then, like the past three months of estrangement hadn’t even been a week, a day.

Tim took a deep breath on his end of the connection. He had read somewhere on the internet about confrontation and getting what you want. He had read all of Karri’s Oprah magazines that kept coming with their Dr. Phil advice. Tim had even renewed Karri’s subscription. He thought he was an expert on recognizing relationship foibles and summits and overcoming. He was prepared for this. Knew what he was going to say to convince Karri to come home, to work out this misunderstanding and make her know that he was a good man, a solid, faithful, loving man.

“Bitch,” is what he said.

And so that conversation hadn’t gone as well as Tim had planned.

After Karri had yelled and screamed and cried and finally, in a tired and quiet voice, let the word “divorce” creep out into their world, Tim hung up the phone, scratched his belly, and went into the pantry. He for aged the potato chips, the oatmeal bars, the gorp, and a marshmallow brownie mix he was certain that Karri had bought well back before Halloween. And Tim ate. He crunched and smacked his way through mountains of oily processed-wheat flour, peanuts, and whey. He had eaten steadily until the word she’d unleashed that day was choked beneath piles of protein, carbohydrates, and both saturated and unsaturated fats.

It was Friday. Tim rolled out of bed and had his bourbon and cigar for breakfast. He looked at the lady’s foot on the phone. Donned his robe. The divorce papers were waiting for him in the mailbox.

“Irreconcilable differences.”

He didn’t know what that meant.

Tim sat at the kitchen table and read through the decree trying to find an explanation. Finally, at the end of the document, he spilled bourbon on the line he was supposed to sign. He held a pen over the puckered smudge, thought he should let the paper dry before flourishing his “Tim Oberman” in the ostentatious hand he used, and got side-tracked by the city letter discarded there beside the divorce decree. Two different sheets of paper: one threatening action for not removing nuisance merchandise, one clearly stating the terms of removal from the union of holy matrimony.

So here it was, he thought. What better time to begin scratching his way out of the passive, suicidal spin he was in? His blood seemed to be pumping a little quicker. The day was brighter. And the ground bedrock.

Tim went into the den and scrounged through his deep and sometimes dubious business drawer and found the number of the six teen-year-old kid who had helped him on the Christmas tree lot all those months ago. The kid had helped unload the trees, set them on their stands, sell them with a smile, and tie them up on car roofs. He was a good solid worker. A first-rate employee until Tim hung out the hand-written “closed until further notice” sign. He remembered the boy was handsome in a Nordic way, all the long hair and the cleft in his downy chin. Tim remembered the hangdog look in the boy’s eyes when he told him to go home the day Karri dropped the bomb, told him he didn’t need him any more, told him pissin’ merry Christmas to you and yours.

Tim felt bad about that last and was going to apologize for it first thing, but the boy wasn’t home. He was at school where he belonged. The boy’s mother had suggested Tim call a fellow by the name of Brick.

“Brick?” he’d asked.

“Yes. Brick,” the handsome Nordic’s mother had said, and gave Tim his phone number.

So Tim called Brick.

Brick answered with a slow, humble, old-Mormon-prophet drawl, “Hello.”

“Hi, Brick? This is Tim Oberman. You were referenced to me as someone who might be looking for a little day work. Is that so?”

A pause, and then the sluggish, retiring enunciation. “Well, yes. I am a body looking for work, yes.”

“I’ve got something for you, if you’d like.”

Another pause. “What did you say your name was?”

“My name’s Tim Oberman. I got some old, ah, trees to clear out.”

“Oberman. Can’t say as I recognize the family,” said Brick. “You live in the ward?”

Tim adjusted the phone in his ear, took a swallow of bourbon. It stuck, and he choked it down, coughed. “I can tell you’re of a good Mormon family. I can hear it in your voice.”

“Yes,” answered Brick, “I am.”

“Me, uh, that is, my family fell away from the Church some years ago, might be why you don’t recognize us. I’m across town anyway. Would n’t be in your ward, but I’ve got these trees.”

“Trees?”

“Yes. Had myself an investment enterprise last winter. Christmas trees. Fell on hard times.”

“Hard times,” said Brick. “I understand, yes.”

“Are you available today? Need to get these trees moved ASAP.”

“You that one down on the highway by the old Safeway?”

Tim finished the finger of bourbon left in his tumbler, glanced around for the bottle. “Yes. That’s me.”

For the first time in months, Tim felt like a man. A man with underlings, and he pulled his BMW 3 Series into the hired man’s driveway. Tim leapt from the car and walked across the dull grass and vivid dandelions to the front door. The house was submissive, submissive and meek like all the other homes in this rundown district on the west side of Payson. He opened the screen door which fell loose from the clasp and rattled with no spring or closer. Tim knocked on the weathered front door. He pivoted there on the little porch and looked down the weary street. It was a neighborhood where mere continuation seemed to be the greatest pleasure of life. Tim realized he must have booze on his breath and slipped a mint in his mouth.

He heard a rustling behind the door. He turned to face a much younger man than he’d imagined standing there in a pair of moss green slacks and a begrimed, short-sleeved, button-down shirt that was open at the collar. He appeared close to Tim’s own age, possibly even younger. Handsome under it all.

“Brick?”

A long pause. Tim was about to say he was sorry, he had the wrong house.

“Yes.” Drawn out, a whole sentence in a word.

“Oh, good, good. I’m Tim Oberman. Nice to meet you.” He extended his hand, grateful to be making a business deal—modest as this one was.

Brick laid his moist hand into Tim’s.

“Are you ready to move some trees?”

A pause, a moment of slow movement, backing up. “Yes. Let me get my gloves.”

In the car, Brick insisted on a short prayer before traveling. He bowed his head, and Tim could hear mumbling and an exhaled amen.

“Thank you,” Brick said as he looked up and smiled at Tim.

“Sure thing. We all have our ways.”

Brick buckled himself into the black leather seat. “Say, this is a nice car.”

“Thank you. I like it.”

While Tim drove out of the old neighborhood, Brick dug at his left ear with the tip of his finger. He twisted his hand with quick jerking motions as though he were revving a motorcycle throttle. Then he started in on the right ear. His mouth opened as he did, and Tim saw he was missing a canine. The man had watery eyes.

“You lived here long?” asked Tim.

Brick worked his ear and then examined his finger. Gave it a good look. “Oh, not in this ward, but I’ve lived here in town most of my life, yes.”

“Are you married?”

Brick’s head twisted and he looked at Tim full on. Tim glanced over. The look on Brick’s face was one of fear and incredulity, a mite lost. Brick turned back to face the windshield.

Tim backtracked, “I mean, ah, if that’s too personal a question, I apologize.” He faked a cough.

Brick said, “You haven’t heard?”

“What’s that?”

After a sigh, “It’s all over town. The bishop . . . son-of-a—” Brick lifted his hands from his lap in fists, held them there in suspension over his crotch. He lowered them against his legs.

“I haven’t heard anything,” said Tim. “You having some trouble?”

“Well, yes,” said Brick, “but I’m not at ease talking to anyone other than my bishop about my worries. I thank you for your concern, though.”

Five minutes later they arrived at the Christmas tree lot. Brick lowered his chin and mumbled some more and unbuckled his seat belt.

The air in the lot was warm and dehydrated. A faint odor of musty pine permeated everything like dried-over forest sweat. Several trees lay on their sides, and there were old newspapers and grocery sacks wrapped around the trunks and tangled in the branches. The trees still held some green in their needles. But it was deceptive. The green was brittle, like old trout bone or diseased and desiccated heart sinew.

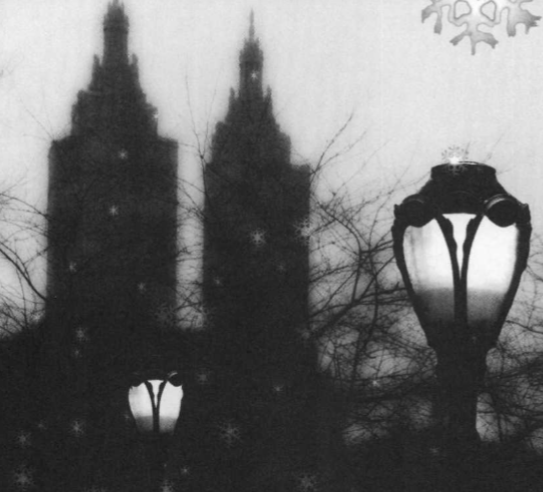

Tim and Brick stood beside the BMW and looked over the sad mess of it all. A long piece of red ribbon, burned almost white from sunshine and weather, fluttered in the top of a Douglas fir, one of the tall ones, a ten-footer. It was as though they were returning to some forgotten place, an abandoned carnival or festival. A May Day celebration gone wrong. The big GMC was there at the back of the lot next to the old Safeway. The truck’s side-paneled bed was filled with trees heaped up on themselves lying on their sides. Shadows hid, buried inside the branches, deep down in, ghosts of Christmas never was.

The two of them stood there and stared at the lot.

Tim said, “Well, I guess the first order is to see if that truck’ll start. We’ll get that load out first.”

He had brought the key from home, though he’d had to search for it. Finally he’d found it in a half empty can of peanuts next to the bed. Tim put the key in the door lock of the truck now. It wasn’t even locked. He opened the door and slid up into the cab behind the wheel, turned the key. The battery was dead.

“I was afraid of that,” Tim said. “How about you move these few trees over so I can get the car in there to jump it?”

Brick took his finger out of his ear and leapt to it. Needles showered off the trees leaving crunchy paths from where the trees had stood for five months to where Brick was putting them now, bunching them together like condemned refugees, each on its own X-ed pedestal. Tim idled the car in up next to the big truck.

While he was hooking up the jumper cables, he asked Brick about his name.

“Is it short for Brickowski or something like that?”

“No,” answered Brick.

“No?”

“It’s just my name. Last name’s Smith.”

“Brick Smith. Hmmm, that’s unusual.”

“Just my worldly name. Will have it only as long as I am tried here on this earth.”

Tim hooked up the cables and let the Beamer’s engine idle a while. He said, “I guess you’re wondering why the trees have sat here.”

“Couldn’t sell them?”

Tim sucked at his teeth, craved the Swisher Sweet in the baggie tucked in the Beamer’s glove box. He wished he had brought some bourbon. “I gave it up,” he said. “My wife, ah, she and I, ah, we had a separation during the holidays.”

Tim hadn’t spoken openly with anyone since Karri had left. He had suffered the division from his wife in isolation. His parents and siblings were not very close. A few kind words of encouragement were all he got from them. It was just as well for Tim. He preferred enduring the drinking and awful smells emanating up from his body in a self-imposed seclusion. A few friends dropped by for the first month, brought him Christmas gifts, tried to match Tim’s drinking while they were there, ultimately giving up or passing out on the couch. They cooed, told him it was going to be all right. Karri would come back. If she didn’t, there were a million other superior women out there who would jump at the chance. After all, he was youngish, established, respected, still had his hair and physique. Well-intentioned flattery, but his body was shot through and his hair was a mess. He was forty-two, and the city was breathing down his neck to clear out his Christmas trees, of all things, in May. Respected? That description was in some serious peril.

Brick was quiet, his finger poised a foot from his ear. He gazed at Tim. The car idled there beside them.

Finally Brick said, “I am sorry to hear that, Brother Oberman, I truly am.”

Tim was getting used to Brick’s slow Mormon cadence. He found it soothing in an odd way. It was as if Brick’s slow deliberate words held more mass, more value.

“Are you divorced then?” asked Brick.

Tim dropped his chin. He drew his hand over his disheveled hair. He looked up at the truck. He scratched his day’s growth of beard, listened to the idle of his car, blinked his eyes. “Got the papers this morning.”

“That is a tribulation. I am sorry.”

The car idled.

“I guess I could rev it.”

Tim got in behind the wheel and pressed the accelerator. The engine whooshed like a vortex, sucking in the air around it and pushing it through its works, converting stillness into energy. Brick slipped into the passenger seat beside Tim.

He said, “I am your kindred in troubles, Tim.”

Tim was the one to show incredulity now. “Your wife leave you?”

“I have had my trials.”

“Your trials?”

The pause.

“Brother Oberman, may I speak to you in openness?”

And then Brick told Tim a story. A story that astonished him. A story of unequaled perversion the likes of which Tim had only heard rumor of, full of all the bits and pieces of every dirty joke and every deep-buried thought of man. A story of love, hate, brawling, balling, propagation, alcohol and drugs, ruination, and, above all, abomination. And at the end of his story, Brick gazed over at Tim and said, “That’s why I pray now.”

“Yes,” said Tim.

“Yes,” said Brick.

“All this, ah, happened?”

“Yes.”

“To you?”

“I am in the process of forgiveness or of damnation,” said Brick. “I often wonder which path I am on.”

The car idled with the jumper cables snaking from under the hood to the truck’s battery in an umbilical connection. Tim and Brick looked out the windshield at the black hood.

“I suppose we should try to get our work done,” Brick said. He smiled, and Tim looked over at him. He could see some gleam in Brick’s eye, a mote lifting.

The truck started with a backfire and a tremble that shook the trees in the bed as blue smoke rose up from under the truck. Tim moved the car, and they got in the truck and drove west to the landfill. Pine needles rattled and blew out in the slipstream.

“Where are your kids?” asked Tim.

Brick fidgeted with his ear. “They are with their grandmother in Salt Lake City.”

“Do you ever see them?”

“I haven’t much, no.” Brick leaned up from the vinyl seat, made it squeak, and pulled his wallet from his hip pocket. He leafed through the scant billfold and pulled out a few photos that were cupped in the shape of the wallet. Brick fanned them out and looked them over. He smiled. “Here they are.” He stretched over the long bench seat and held the photos up for Tim to see.

There was a boy, about seven with white hair and crossed eyes; a girl a couple of years younger, missing a tooth like her dad; and an infant that looked to Tim like the very embodiment of peace. The baby was in a woman’s arms. The photo showed the woman’s lap, an elbow, part of her nose and chin and a spill of chestnut hair over her shoulder.

“That’s my wife holding Chelsie. They’re all a little older now.”

Tim thought about showing him the lady’s foot stored in his phone photo archive.

“Must be hard,” said Tim. “Is your wife still around?”

Brick settled back in his seat, put the photos in his wallet and put the wallet back in his hip pocket. He sighed. “I don’t know where she is. Bringing pleasure or pain—or both—somewhere I am sure.” He revved his ear with his finger.

The truck engine droned on. Pine needles glittered into the warm afternoon and settled onto the road.

“Ah,” Tim started after a long silence, “how do you, I mean, how does that happen? You know, I mean, I feel like I know what is going on around here. I mean I’m not a prude or anything. I’ve been around. I just never knew all that kind of stuff was going on. I mean, this is Utah.”

Brick watched the fences line out along the field road they were traveling down. He dropped his face and then looked up. “I don’t know. It’s what’s behind doors.” He lifted his hands over his thighs. “It’s fun, you know. I had a blast. I . . . ” He sat there with his mouth open. Words stuck. Then, resigned: “How does anyone know when Satan is at work on them?”

Dust billowed up around the cab as Tim stopped the truck at the landfill gate next to a tiny shack. A lean man who looked as if he were undergoing chemotherapy slipped out of the shack and stood with his legs apart and arms crossed and looked in at Tim. Tim rolled down the window and offered the man his driver’s license.

“Got a permit?”

“I’m a resident.” Tim pushed his license toward the man again.

“Don’t matter.”

“What do you mean?”

“Won’t take that much yard waste without a permit.” The man turned and went back into the shack and sat on a tall stool. He flipped open a dusty, ruffled Playboy magazine.

Tim shouted, “Where do I get a permit?”

“City.”

“Hmm,” Brick murmured. “Unhelpful little jerk there.”

At the city offices, Tim got the runaround. No one seemed to have heard of the need for a yard waste permit. It was a mystery. Finally, he told the snooty man with greasy hair at the front desk to go kiss the mayor. And then Brick added, “And the governor, too.”

“I’m sorry. I don’t understand why the man at the dump told you you needed a permit,” the man’s shrill voice raised to reach their backs as Tim and Brick wandered down the hall and out the door and down the steps into the fine afternoon.

“I need a drink,” said Tim.

Brick chuckled, “I don’t blame you.”

“Well, tell you what,” said Tim, “These trees be damned. I’m going home for a nice tall cold Manhattan. You want to join me?” Then he looked at Brick. “I don’t mean to tempt you. Your struggles and all.”

“Well. I’m coming with you, sure. As for the drink, I prefer straight Scotch.”

Tim looked at Brick. Brick was walking to the truck with his head up. He appeared to be grinning and his shoulders held a degree of straightness—even his green slacks had a jump in them that wasn’t there before.

“I’ve got Scotch,” said Tim.

“Single malt?”

“Blended. Cheap.”

They got in the cab and slammed the doors. Brick bowed his head and prayed.

“Praise our Heavenly Father, I’m ready for a drink,” Brick shouted after his amen, sounding more like a jubilant Baptist than an old Quorum-of-the-Twelve Mormon.

“You sure?”

“I feel the Spirit in this, Brother Oberman.”

They drank through the afternoon at Tim’s house on the back patio under the deck umbrella. The truck sat out front in the driveway full of Christmas trees. Brick told more stories of sin and debauchery, his suffering for redemption, and the need of forgiveness from his children. Tim opened up about his wife and their problems in the marriage. Brick gave advice and clucked his tongue and prayed and quoted scripture and prophets. They drank bourbon and Scotch and beer and smoked Swisher Sweets. They argued the finer points of the Word of Wisdom. They relieved themselves in the hollyhocks lining the patio in full view of Tim’s neighbors. Brick bore his testimony. Tim promised to go to church with Brick on Sunday. They got to know each other, agreed and disagreed, made pacts, and before long the sun found its way down in the west and the air gathered cold. They sat in the gloom and felt each other’s presence like a warm vapor circulating on currents of barely whispered breath. From out of this slow, calm broth, they determined what was to be done with the trees, talked it through, saw the plan, the first plan. They waited. At midnight they got to it, shook themselves, rising from the patio like stone men resurrected.

It was 2:00 A.M. when they finished. The quarter-waxing moon was long gone down in the west sky. Tim and Brick had piled all the trees in the center of the lot. Their arms were scratched and marked from branches and needles. They were tired, the adrenaline and Christmas songs exhausted from their systems.

“Our finest gifts we bring, pa rum pum pum pum,” Brick trailed off and was quiet. They sat in the back of the empty truck. “Shoot, I miss those kids,” he said under his breath.

Tim looked at the dark mass of trees in front of them. He pulled out the divorce papers he had stuffed in his pocket.

“You gonna do it?” asked Brick. The last of the Swishers dangled from his lip. The cigar was burning hot and dry. The red spot of coal seemed to breathe a few inches from his face.

Tim slipped off the truck. He walked up to the edge of the tree pile. He was sober. He lifted his torch cigar-lighter and flicked it. Butane mingled with the pine scent. Tim held the hissing flame near the divorce decree, read Karri’s name typed clearly there on the front page. Plaintiff. His name below.

He had no defense. But he could try.

He let the lighter go out, and he folded the decree and put it back in his pocket as he walked to the truck.

“Plan B, then?”

Tim sat down next to Brick. “Yeah,” he said, “I suppose.” He took out his cell phone and opened it to the lady’s foot. Looked at it and sighed, then: “u-u-A-A-Ah!” He lurched up and threw the phone into the pile of trees. The light from the phone was swallowed up by the branches and needles. “I’ll get a new one tomorrow.” Tim breathed out and settled back down into the bed of the truck. “I’ll call her. And the city, too.”

Brick took the cigar from his mouth and studied the hot tip of it. “Not gonna miss these,” he said. He leaned up and threw the cigar at the trees. It turned over and over in the air and disappeared in an explosion of sparks as it struck a Douglas mid-trunk.

“You feel like praying?” Brick asked. He stuck his finger in his ear, held it there frozen for just a moment and then took it out.

“I guess it wouldn’t hurt,” said Tim.

For a while there was nothing, just the cold silent air of a May night, both men reciting quiet appeals to their respective higher powers. Then the glow started from deep in the pile. And the crackling grew, some pagan deity coming to life. And the men who brought forth this Christmas demon fought the urge to run, to hide, and they leaned back on their elbows, humble and amazed under the tongue of fire that roared all their collective love and hate and fear in a strange and beautiful voice at the darkness above.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue