Articles/Essays – Volume 40, No. 1

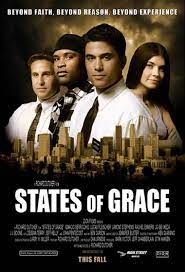

Choices, Consequences, and Grace | Richard Dutcher, dir., God’s Army 2: States of Grace

Richard Dutcher, the founding father of Mormon cinema, has much to be proud of in his third film, God’s Army 2: States of Grace. His first effort, God’s Army, was a missionary bildungsroman with a heavy emphasis on priesthood ordinances. Brigham City, his second, was a murder mystery exploring the limits of a rural theocracy and the contingencies of moral stewardship. Stares of Grace is both more ambitious and more nuanced than these prior efforts.

A sequel primarily in name, States of Grace follows several story lines intersecting with the protagonist, Elder Lozano, a former Latino gang member on a proselytizing mission in Santa Monica. (Warning: The discussion that follows may spoil the film for those who prefer to be surprised by the plot) He serves with a rigidly pious junior companion (Elder Farrell) and meets a sexually distressed aspiring actress (Holly), an alcoholic street preacher (Louis), and an African American gang member (Carl). Loiano affects and is affected by each of them in complex, unpredictable ways.

Though States of Grace is superficially a story of gangland salvation and alternative visions of God’s grace, it is also an exploration of choices and their consequences. This problem was framed for me by a freshman-year misinterpretation of Harold Bloom’s trademark Hie Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1973). Where Bloom intended a poet’s fear of being derivative, negotiating an awkward relationship with creative forebears, I understood my own great fear of influencing others. As a missionary, as a friend, as a counselor in the bishopric of a student ward in the East, as a lover, a child, a sibling, now as a parent, I have worried often about the implications of influence, the ripples in die spiritual fabric that occur with each decision I make.

I am in good company in this anxiety. From Paul’s obsession about sharing meat with pagans to the Mormon aversion to wine in the Lord’s supper, to Book of Mormon preaching on human agency, to our near-compulsive record-keeping, we as a people worry about the influence and implication of our decisions. Dutiful Arminians, we exercise our wills, recording successes and dreading failures. Within our proselytising, we take special pride in marking our converts and their future generations in a recursive calculus of salvation. How great indeed is our joy in bringing our carefully recorded kindred to God; what better emblem is there of our will rightly exercised?

Dutcher’s Lozano is just such a convert, a former gang member brought to the Church on the eve of his first murder who then chose to bring the gospel light to others. Unfortunately, he has violated his covenant. By his own admission “a better convert than a missionary,” instead of expanding the gospel influence of the elders who converted him, he has been counting the days until his release.

The film’s narrative begins during a protracted game of basketball. Lozano witnesses a drive-by shooting and helps to staunch bleeding from gunshot wounds that threaten Carl’s life. In that Samaritan moment, Lozano is transformed.

In the aftermath of this chance encounter, a spark of good, old-fashioned enthusiasm is kindled in Losano’s soul, and he begins to open his heart in a progressive way, drawing in Louis, the (poorly acted) preacher, while he simultaneously Teaches out to the isolated Holly and actively proselytizes Cail. In the process Carl is baptized, Louis’s soul is presumably saved, Holly deflowers and devastates El der Farrell (who flees his guilt by slashing his wrists), and Carl’s barely pubescent brother is murdered.

In the end, we hope that Carl’s soul was saved when he interred his weapons in his grandmother’s garden, buried in conscious imitation of the Ammonite pacifists. We hope desperately because we have seen the price paid for this one convert, and it is exorbitant.

But we are not entirely sure that Carl’s soul has been saved after all. Enraged by his brother’s murder, the newly baptized Carl seeks vengeance on the killer, a callow but sinister Latino gangster. Carl, exhumed revolver in hand, turns dramatically to Christ when his intended victim prays for mercy, and he holsters his weapon at the last moment. But his repentance comes too late. As Carl steps away, his own gang friends execute the praying boy.

Is Carl saved after all that Lozano has caused to be sacrificed on his behalf? Legally we know that Carl is now accessory to second-degree murder, and morally we sense that it was Carl’s blind rage that set in motion the events leading to the murder. The answer isn’t at all clear; grace for Carl is buried in the mud that once enclosed his weapons. In an over-stylized but apt juxtaposition of human circles—elders confirming Carl and gangsters circling his brother’s fresh corpse like self-conscious vultures—Dutcher further argues that Carl’s conversion is connected to his brother’s death. Carl’s brother took vengeance into his own hands explicitly because Carl had buried his weapons and chosen peace; had Carl waited to reform, his young brother might not have died. Aftershocks again, unpleasant ones, of Lozano’s Samaritanism.

The film closes with a distractingly stylized paean to the Christ child, as the major characters are left to confront the complex ripples in the substance of their humanity initiated by Lozano’s decisions. Dutcher reminds us that salvation is worked out in interconnected communities as well as in the personal encounter with the Christ. The only absence from the final assemblage is Elder Farrell’s father, whose statement of conditional love (in rough paraphrase) “I’d rather have you come home dead than dishonored”), Dutcher places at the fountainhead of the blood flowing from his son’s slit wrists.

The jumble of consequences and tenuous salvation strikes deep at the Arminianism of contemporary Mormon praxis. Lozano’s response to the spirit of compassion met with disastrous outcomes; Farrell’s kindness to Holly led to his devastating transgression; Brother Farrell’s pious rigidity is implicated in his son’s attempted suicide. In this closing devotion to the Christ Child, Dutcher claims a grace-emphatic Atonement. The outcomes of our exercised wills may be hard to guess at or predict; in the end, we can only seek to be true to the presence of Christ.

It is the mark of a great theoretical divide that Dutcher’s organizing vision, however clearly portrayed, is open to various interpretations. An earnest Arminian could easily exclaim that all of the tragedy in the film was the result of wickedness, that Lozano’s transgressing of mission rules invalidated any Christian sentiments he may have experienced. The complexity of Carl’s near-salvation is simply the wages of sin. In this view, the Atonement validates the careful, steadfast, and predictable control of the will. A more grace-focused viewer might see the film as a witness to the difficult-to-regulate complexity of human experience. In this vision, the rule that we must follow is the individual experience of the Atonement and the recognition that we are all interdependent in surprising ways. God, Dutcher suggests, may be willing to pay ridiculous prices for healing his children. His troubled children will remain able to do little more than guess at the shape of their lives, confident only in his unconditional love and its expression in divine grace.

Richard Dutcher, writer/director. God’s Army 2: States of Grace, 2005. Movie, rated PG-13; two hours, eight minutes

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue