Articles/Essays – Volume 39, No. 1

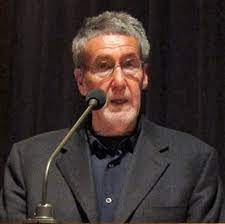

An Interview with Darrell Spencer

In addition to many stories in quarterlies, Darrell Spencer has published four collections of stories, Bring Your Legs with You, Caution: Men in Trees, Our Secret’s Out, A Woman Packing a Pistol, and a novel, One Mile Past Dangerous Curve. Darrell’s honors include the Drue Heinz Literature Prize and the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, easily two of the most distinguished prizes for the short story offered in America. For Darrell, his “life is about writing and what it means”-inventing a world, rather than mirroring one—and he hopes “to write stories that will break your heart.”

Douglas: What got you started writing, the original impulse? Did you always think of yourself as a writer or was it adult-onset?

Darrell: Reading. That’s the answer. Reading. Which I came to late. I didn’t really start until I went to college. You don’t count Fielder from Nowhere, Hard Court Press—the kind of books I read growing up. You hear about writers reading Moby-Dick when they were five years old, part of their journey through the local library, book by book, end to end, top to bottom. They discovered Kafka at age seven. Wrote novels before they were ten. Makes me feel stupid. I was collecting baseball cards and trying to figure out how to avoid getting spiked when some kid slid into third.

No, I did not think of myself as a writer. Me, a writer?—the thought never occurred to me. What I wanted was to be trickier than Bob Cousy and play for the Boston Celtics, but I learned early and profoundly and without question that I didn’t have the talent.

So I got to college, was thinking about law school, and then I read Faulkner. As I Lay Dying, first. That was a class assignment. Next, Light in August on my own. I bought all his books. Absalom, Absaloml He reset me, turned my world sideways. I read Fielding—what a swarm of words—and tried to imitate him. Used sagacity and negotiant and victuals in the opening paragraph of a seven-hundred-page novel I was going to write, but of course never did. I was twenty-one at the time. Even then it didn’t occur to me that I could be a writer. For people like me, that wasn’t in the cards. What I needed was a job and a paycheck. Bread on the table. Tom Jones led me to what was then a contemporary novel, John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor. Great fun is that book. I discovered the writers who were alive and writing and began reading them.

The impulse to tell stories must have been in me because I can recall only one assignment from high school. Mr. Butterfield asked us to write a short story. I was never a good student, not in high school, not in college, not until graduate school. But I worked hard on my short story. In the end, it was terrible. Shameful. Particularly when you think about what someone like Truman Capote was producing when he was a teenager. Lee Smith talks about one of her early college-day attempts to write fiction; in the final scene, a house has burned to the ground, and a family has died—I think it’s Christmas Eve—and the only sound is a music box playing “Silent Night.” She cites the story as an example of her early failures, as a story driven by its own melodrama, but I imagine it as better than mine. The short story I wrote for Mr. Butterfield was about a sixteen-year-old who has saved up and bought his first car. He’s going on his first solo date. We follow him on his drive during which he passes images of his younger self. I chose three images. Had to be three. There’s significance in three, right? Three wishes. Three visitations. Three strikes and you’re out. There’s heft and every possibility of truth in three. At one point, he has to brake to avoid hitting a kid dribbling a basketball. He reaches his girl’s house, rings the bell, and then glances down at his shoes. There is one spot of mud on the toe. Symbolism. Profundity. What I knew back then about writing stories I had learned from literature classes, classes that teach us how to read texts and the world in sophisticated ways, but that are not the best training ground for a writer. As I said, the story was terrible. I got a C- on it. But my point is that it mattered to me; it’s the one thing in high school I cared about. I wanted to write a story that knocked Mr. Butterfield’s socks off.

I have to mention John Berryman. There are incidents that take us on a 360 turnabout. You go in a door and out the same door, but you’re different. My wife, Kate, and I were living in Las Vegas. I had given up on school. I was painting signs for a living, fourteen-by-forty-eight-foot billboards, doing show changes for Elvis, Wayne Newton, Buddy Hackett, putting highlights on the nose of the clown for the Circus Circus, doing pictorials of the Coppertone dog. Kate and I went to the mall one night. She was checking on a book she had ordered, and I wandered over to the poetry section. No reason for it, but I picked up Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs. I had never heard of him, and I had never read anything like his poems, which were colloquial and rude and ill-bred, yet tight and rigorous in structure. Voices jigsawed together. Celebratory and mean-spirited. Retaliatory, yet full of love and joy. I am still, thirty years later, memorizing his poetry. Right now I’m working on his Eleven Addresses to the Lord. Berryman—eventually I would learn what a highly respected scholar he was—had no truck with decorum. The book was a carnival. Was like a mob. His poems are part of me.

The first serious thing I wrote—I was in graduate school by now, University of Nevada, Las Vegas—was an imitation of Berryman’s Homage to Mistress Bradstreet. I was homaging Virginia Woolf. Not her fiction. I was reading her letters.

So the one-word answer to your question is reading.

I fell hard for words. Even how they sit on the page, which has to do with sign painting, I suppose. You eyeball lettering. It’s an art. Fit and fix together. You have to know that “O’s” dip below the bottom line and “A’s” intrude upon and adjust in odd ways to the surrounding letters.

Do your remember diagramming sentences in grade school? I couldn’t admit it to my basketball-playing pals, but I thoroughly enjoyed diagramming sentences. Miss Leach, sixth grade, John S. Park Elementary in Las Vegas. One sentence on the blackboard laid out like an overhead photograph of the city of itself. That, too, has something to do with my desire to write fiction.

Douglas: How would you characterize your style? Some have called you a minimalist, or said that, in some ways, you’re like one. Are you? If so, why? What are the advantages?

Darrell: A minimalist? No. Maybe the stories in my first book, A Woman Packing a Pistol, are somewhat minimalist. I’ll confess to that, though I don’t think of them in that way. I was reading Ivy Goodman, Mary Robison, and what people call early Raymond Carver.

Cheryll Glotelty, who teaches at the University of Nevada at Reno, contacted me because she wanted to include a story of mine in a Nevada literature anthology. I think it’s titled Home Means Nevada: Literature of the Silver State. She sent me the headnote for my story. It began, “By writing experimental fiction, Darrell Spencer … ” I phoned. Said, “Experimental?” All this in a friendly way. We talked and then she wrote back. I need to mention that what she was including in the anthology was a short-short titled “My Home State of Nevada.” She suggested “avant-garde,” “postmodern.” No. No. She sent me her brainstorming, talked about fiction that skirts the edges of realism, fiction that displaces reality and refuses to be taken literally.

I kept thinking, They’re stories; that’s all. There is nothing avant-garde or experimental or postmodern about them. They’re told in a straightforward and direct way. They’re stories about folk walking about on the planet and trying to figure out how to live in particular ways.

I can’t remember what we decided on. It’ll be interesting to see what the headnote says when the book comes out.

I designed and taught a course in minimalism here at Ohio University. We read Amy Hempel, Ann Beattie, some Marc Richard, and Janet Kaufman. We read Carver and Mary Robison’s Why Did I Ever, a novel that gathers on you like a breakdown.

Kim Herzinger edited an issue of the Mississippi Review that is devoted to minimalist fiction, a give and take, a few writers lamenting minimalist fiction’s presence in the world and other writers celebrating its being here.

What you end up talking about in a class is contracted language that is blunt, clean, spare, sparse, exacting. Sometimes my language is contracted. I hope it’s exacting. You talk about elliptical structure and form. Sometimes my work is elliptical. You talk about dislocation. You talk about silent surfaces. One class period I brought in an Ann Beattie story, a recent one, a nonminimalist piece. I had cut all the exposition from it—paragraph by paragraph, line by line. I asked the students to account for the action—to see if their exposition (why is the husband being rude to his wife?) matched the exposition in the original story. We also did a line-by-line comparison of Raymond Carver’s “The Bath” and “A Small, Good Thing.” What you learn is that what is not there on the page is present in the white space.

I admire minimalist fiction, but, no, my work is not minimalist. If we were to run through a list of styles, I would say to each one, Yes, and no. I don’t mean to sound wishy-washy, but I don’t know how to describe my style. Maximalist? Nah.

Douglas: What do you strive for in your fiction? How do you want it to affect your readers? What should delight and please them, entertain them, in your work? Do you have a special audience in mind?

Darrell: Barry Hannah says the brain got to sing. I can’t sing. Not a lick. Or dance. Wouldn’t you love to ballroom dance like the pros? Get dressed to the nines. All that footwork, the choreography of passion. Or hoof it. Tap dance. Foxtrot in shining shoes.

I can’t sing and I can’t dance, so I write. And what I strive for is that my work will sing and dance. I think of my fiction, each piece, whether it is a short story or a novel, as a repository of language. When I talk to friends about this, I find myself making a kind of bracketing shape with my hands, fingers curved as if I’m holding a small pot as an offering, or as if I’m stretching open a gunny sack. I hold my hands out in front me, like I’m struggling to contain something that doesn’t want to be contained, and I say, I want to drop you in this bag, pocket, bucket, this pot—this repository. Jump in. Enjoy.

I like slang. Argot. Jargon. The colloquial. Vernacular. The demotic. I try to entice readers into an experience with a particular brand of language, such as, in a specific sense, the jargon of sign painting or roofing, or, in a broader sense, the language of loss or grief or joy. Each piece contains, I hope, at least ten cats in a bag.

Almost every story I have written has begun with a line or phrase that I overheard or one that popped into my head. I’m writing one right now called “Can I Help Who’s Next?” Nothing startling about that question, and, having eaten a lot of Subway sandwiches, I’m sure I’ve heard it dozens of times. Then one day I finally really heard the sandwich-maker say it. So I started a story. It seems to me that that question is a repository of language, that it contains all I need to know. It is as if once I write the words down, they gather to themselves all the other words I’ll need to tell a story.

I’m also interested in story telling. I want to tell stories that break your heart. But my fiction is character driven. I don’t see much plot in it. Plot doesn’t interest me.

My work is, I hope, baggy. Off-shot. Disjointed. Unwieldy. I hope my stories, like John Berryman’s poetry, won’t hold still. Years ago I read an article about an architect named Gehry. The author said that Gehry did not accept the biblical idea that a house divided against itself cannot stand. Instead, Gehry believed that a house divided against itself would—I’m pretty sure this is the word the author used—flourish. Such a house will astonish us. I want my work to be divided against itself.

I hope each sentence I write sticks to the page and delights a reader, not so you stop and take note or underline anything. There is a certain kind of delight we experience on the move. Are we back to dancing? Prob ably. But also I’m talking about the delight you feel when you strike a nail exactly as a nail ought to be struck. I hope my stories have some humor in them. I hope they don’t come across as clever. That would make me very sad. I hope the characters entertain readers. And count. I hope the events and characters matter. Flannery O’Connor tells us that she loaned a few of her stories to a country woman who lived nearby. When the woman returned them, she said, “Well, them stories just gone and shown you how some folks would do.” O’Connor adds that that is where you have to start, with “showing how some specific folks will do, will do in spite of every thing.” That knowledge drives my own work.

Douglas: What are your themes, the things you are trying to say in your work? Or are you trying to say anything? Are there values you keep punching?

Darrell: I’m a member of Chekhov’s tribe as far as theme is concerned. I’m trying to take what Chekhov calls an intelligent attitude to ward what I write about, but I’m not trying to convey a theme. I have no points to make or argue. No scores to settle. No axes to grind. Okay, one or two axes. Chekhov tells us that a fiction writer is not under obligation to solve a problem; an artist’s only obligation is to state the problem correctly. Obligation is Chekhov’s word.

We need something in this world that isn’t trying to teach us lessons or get us to buy a product, that isn’t self-helping us to death. All writing, fiction included, is, of course, loaded with bias and it certainly signifies—it distorts and deforms and jerry-builds—but fiction can draw us into a simulacrum of experience itself. We need that. We need work that isn’t trying to tell us how to act.

William Gass says of his fiction that he wants to plant an object in the world. I think I’m close in quoting him: “I want to add something to the world which the world can ponder the same way it ponders the world.” He makes it clear that he wants the object to be a beautiful object and that beauty is not to be subservient to truth.

There you have it. Beauty and truth: two cans of worms you don’t want to open. Try talking intelligently about that pair, and you’ll end up tripping over your own tongue. You’ll end up deconstructing yourself word by word, talking and walking backwards, erasing yourself as you speak. Rewinding.

What I say to my students about beauty, about measuring one piece of writing against some standard, is that I’m going to ask Mikhail Baryshnikov to dance across the front of the classroom. Then I’ll dance. And they’ll notice a difference. Sure that comparison fails—culture is at the root of all judgment—but isn’t that the pleasure of analogical thought: that it fails: that it celebrates, in the end, difference.

Gass and Chekhov both agree that part of the issue has to do with the way fiction works. Combine art and sermon? Chekhov asks. Would be pleasant, he says, but not possible because of what I believe he calls matters of technique. Fiction speaks the voice of what—character, event, circumstance, situation—it depicts. Gass wants us to turn the moral issues and problems over to the rigors of philosophical and scientific thinking. He doesn’t trust fiction. Fiction, for him, must not assert. I hear people say that fiction lies to tell the truth. I don’t buy that. Fiction lies, and it distorts in order to depict and wonder. It wonders. The fictive experience can be—is?—as real as any other experience—as if there is any other kind.

I’m in these two camps, and Gass and Chekhov have said eloquently what I feel, so I thought I’d pass their words along. Nothing originates with me. Their views inform my sensibilities as a writer.

I want to add one more thought. I’m trying to explain what it is I’m after in my work. We know that all the stories we tell are texts that refer to other texts—story (small “s”) refers to Story (big “S”). Call Story with the big “S” myth or collective unconscious or master narrative or arche or form. Call it whatever you want. What I’m saying relates (maybe only in my head) to what Vladimir Propp discovered when he analyzed folktales: that they’re made up of functions. The second function of a folktale is what Propp calls the interdiction. Someone is warned not to do something. Don’t go into the woods. You can hear some zealots: Don’t go into the words. Don’t go downstairs. Don’t go to the far kingdom. When I was a kid, it was, Don’t cross Oakey Boulevard. But, of course, the interdiction is violated so that the tale begins. Interdiction and violation, two members of Story, the one with the big S. Or we can talk about Story with the big S in other terms: Greenhorn comes to town. Hero goes on quest. Someone is expelled from somewhere.

What I’m trying to say here is that I’m aware of all this as a writer, and there’s one thought that drives me when I write: Traduttore, tradittore. To translate is to be a traitor. To translate is to traduce. Recently I taught a class in form and theory here at Ohio University. It was guided by a phrase from Derrida’s The Retrait of Metaphor: “(a ‘good’ translation must always abuse).” When I say that the small-s story refers to the big-S story, I mean that it translates the master narrative, the myth, but does so, when it is well done, in an idiosyncratic way. I want my work to be a traitor to that big-S Story; I want it to traduce that big-S Story. Abuse it in some exacting and idiosyncratic way. John Caputo says to do so is to commit scandal, is to tell the story in a treacherous way.

If I have a theme, that’s it.

I’m not saying I think about any of this when I write. I don’t. You can’t will any of this into being.

Douglas: You’ve won both the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and the Drue Heinz Literature Prize. How has winning those prestigious short-story competitions affected you? Any other prizes or awards you plan to go for?

Darrell: I feel lucky to have won the awards, and I’m grateful to the people who chose the books. The awards have affected me because they mean that two more of my books are now in print, are out there for people to read.

Douglas: Virtually all of your success has been in the short story, but you recently published a novel with the University of Michigan Press. Why the switch and what’s the difference for you between writing stories and a novel? Do you see yourself leaving the short story to write novels? What advantage does the novel hold for you over the short story, if any?

Darrell: The novel is titled One Mile Past Dangerous Curve. I haven’t actually switched from short stories to novels, although the publication history makes it look as if there has been a changeover. All the time that I was writing stories I was writing novels. Failed novels. Bad novels. I wrote two that I threw away. I have been revising a novel titled Welcome to Wisdom, Utah for almost ten years. Right now, I’m finishing up a book titled So You Got Next to the Hammer. It contains two novellas and five stories. The novellas are novels I cut and cut and cut. A few weeks ago I started a novel I’m calling The Department of Big Thoughts. It’s about—is told by—one of the characters in my book Bring Your Legs with You. He’s a roofer and a thinker. What he is is one more big-time talker on the planet. So I’m writing that novel, but at the same time I am writing short stories.

I write novels and stories in the same fashion. One Mile Past Dangerous Curve began with a sentence I overheard, a sentence that disappeared from the book a long time ago, a sentence that is no longer in play. The working title was The Devil, You Say. I plumbed those words for all I could get out of them. Stories require weeks of revision; the novel took years. But I think that’s an obvious thing to say. I wish I could say something smart about the difference between the two forms. This is true for me: Language and character can carry a story. I tried to let character drive the novel, but 1 found that for each major revision I wrote I was restructuring in order to satisfy my desire and itch for plot. Maybe a better word is event. I was into a third or fourth draft when I realized that I was spending the first fifty or sixty pages caught up in a riff triggered by the opening paragraph. It hit me that I could move one of the key events up and that in doing so I would be upsetting the ground situation.

I don’t think one form has an advantage over the other form. I acknowledge the major differences, but it’s all writing and trying to create the immediacy that is essential to fiction. In practical terms, I like the short story because I can pretty much keep the whole piece in mind as I write. I can tweak the story at one point, knowing exactly what changes that will require three, six, nine pages later. I can make a change near the end and I know where I have to go earlier in the story to make adjustments. It’s difficult to keep an entire novel in mind. When I’m finished with a story, I hold an image of it in my mind. One story was held together by a picture of a woman sitting in a chair in her front yard. I wasn’t able to do that with the novel. It’s driven by an image, I think: bafflement. If that’s an image. It can be. The sound of the word. But, again in practical terms, it was difficult to keep all of the characters and conflicts and situations in mind. For example, late in the publication process—I think we were in galleys—I was rereading a section where I had done some revision, and I discovered that a character was both in the house and still sitting outside the house on a redwood table. An egregious error, but there it was.

A novel, a story—each is written one sentence at a time. You write a sentence, and you listen, and the next sentence responds to it. They bump against each other. You like how they join each other, so you write the next one.

Douglas: What are the major literary influences in your life as a writer and why? Which writers do you value most?

Darrell: I’m going to start by side-stepping your questions somewhat. The major influence on my work is actually my wife’s painting. I want to write fiction that is like her art. One of her paintings is the cover on One Mile Past Dangerous Curve. The people at Michigan were kicking around ideas for the cover, and I told them about the painting. I wish I could write the way she paints. Her work is referential, is representational, but the color, the texture, the shapes, the brush strokes—all of the elements of her art resist lending themselves to picture. There is a remarkable give-and-take going on. I will badly recount this story, but Ernest Gombrich, in one of his books on art, tells us about a famous art critic de scribing an experience he had with a painting by Velazquez. The man kept walking up to the painting and then back away. Up and back. Up and back. He wanted to experience the moment when the paint and brush strokes transformed into a boat. The story goes something like that. Kate’s work exploits that kind of tension, and I want to write stories that do so with language. Our friend, Wayne Dodd, bought one of Kate’s paintings. I was talking to him about it one day, and he said, “Her work talks back to you.” Yes. He was dead-on right. I want my fiction to talk back to you.

Now the literary influences. I’ve already mentioned Faulkner, who wasn’t an influence as much as he was an impetus. I studied the canon in school, and I hope I learned from writers like Flannery O’Connor, Melville, Hawthorne, Gertrude Stein, Kate Chopin, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison—the tradition, the masters. You know all the names. What I was doing was catching up and learning what art is. No one, at that time, was teaching Saul Bellow, but I found my way to him. The Adventures of Augie March-difficult to describe my response to that novel, what it meant to a young man trying to find his way into writing. No one was teaching Thomas Pynchon either, but I read him. Eudora Welty, Capote’s In Cold Blood, F. Scott Fitzgerald. Well, the list seems endless, so I’ll stop.

The writers whose work made me feel as if it was okay for me to write are contemporary writers. I’ll name some names, but first have to say that Francois Camoin was the writer whose presence and work influenced my own writing more than anyone else did. I once tried to figure out a way to describe Francois’s fiction. When I think about his work I always think the sentences, the sentences, the sentences. They are precise. Exact. Hard-cut. I told him I imagine him as Kurtz in The Heart of Darkness, only Francois is truly smart, and not mad, although his work can be scary. He has sounded the human heart. I see him making sentences in an unlit place, one small circle of light on the words he fiddles with. He shuffles them about. He rolls them like dice. Tosses them into the air. You see his hands—busy, busy, busy. Berryman begins the first of his Eleven Addresses to the Lord thus: “Master of beauty, craftsman of the snowflake.” In that spirit, I think of Francois’s sentences, his stories, his books. Isn’t there a tale or myth about an artisan who forged a sword so brilliant and sharp it could cut air? It had to be put away by the gods, kept from the hand of human kind. The universe was at risk. Francois’s sentences—there you go.

And you, Doug—your fiction, which was important for me to read, also taught me to pay attention to sentences. Not one word wasted. Another good friend at BYU, Bruce Jorgensen, once wrote a quote from Chekhov for me. It still sits on my desk. Chekhov was writing to a friend of his; the two of them were discussing fiction writing, and Chekhov wrote back: “Your laziness stands out between the lines of every story. You don’t work on your sentences. You must, you know. That’s what makes it art.” My wife says Bruce’s own writing is full of heart. It is. Truly. And there is not one lazy sentence in it.

It’s inevitable that I will forget some influences if I try to name names, but I would rather be accused of forgetting than risk not paying tribute. These are the writers whose work makes me want to write; I can’t read anything they’ve written but that I want get up, go to my desk, and write. Stanley Elkin, Grace Paley, Harold Brodkey, Barry Hannah, Amy Hempel, Mary Robison, Frederick Bathelme, Lee K. Abbott, Kate Haake, Debra Monroe. There are dozens whose work taught me (William Gass, John Barth, Alice Munro) and whose work I greatly admire, whose work is the good news, if only people would read it.

Douglas: Earning a doctorate seems to damage some fiction writers, distracts them from what they want most to do. But that didn’t happen to you. What was your University of Utah doctorate like? Do you think of it as making you a better writer, or not? Was it a good experience?

Darrell: Good things happened to me at the University of Utah. It was a terrific program then, and it still is. I met working writers. Leonard Michaels came in for a residency. I drove William Gass around in a snowstorm, which led to a story I wrote called “I Could of Killed Bill Gass.” I tossed that one away a long time ago. It was important for me to meet writers. Not because of what they said to me about my work, but because their being what they were made writing fiction seem a possibility. Legitimatized it for me.

The scholarly work at the University of Utah was as important to me as the fiction-writing workshops. In fact, in certain ways it was what I really needed. I became interested in narrative theory, and I read what I could get my hands on—Gerard Genette, Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, Seymour Chatman. The list is long. Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida. I wasn’t reading theory in order to learn how to write. I was intrigued. Think how it might affect a writer to have running through his veins Heidegger’s idea that truth is untruth, that the work of the work of art is to enact the eternal strife between concealing and unconcealing, that when the artist lights up a space, that lighting itself darkens the edges. Here’s one that I will never forget: “The truth of things lies in the event of their thinging” Ha. Don’t you hope your own writing things?

All this has to do with writing fiction, but I am not in any way suggesting that I think about any of it when I am writing a story. You can’t impose strife on your work; you can’t will thinging into a piece about a kid growing up in Pahrump, Nevada.

But the concepts bounce about in your mind and they can’t help but influence your work. You asked about style earlier. I don’t know what my style is, but I do know that it is what it is—not directly, but because the idea sits on my heart—partly because of my understanding that the life of a metaphor lies in the fact that it practices (Derrida’s notion) difference not in similarity.

The University of Utah also placed me within a community of writers. There may have been competition there, but I didn’t feel it. Or it worked in beneficial ways. I made friends, writers who have gone on to great success, who have kept in touch, whose work I turn to when I need to be reminded that what we do can matter.

Certainly a degree in writing, whether it’s a Ph.D. or an MFA, is not what everyone needs. I can see how a degree might slow a writer down. But you’re learning. How can learning hurt a writer? I hear people say that writing programs produce a sameness in the fiction. That’s hooey. I would bet that you could list a bunch of fine, fine writers, and ask those critics—assuming they don’t know beforehand—who had MFAs, Ph.D.’s and who didn’t, and the critics wouldn’t be able to guess based only on the work. The only danger might be that a young writer isn’t ready to accept workshop criticism that is helpful and ignore workshop criticism that isn’t.

Douglas: What were your BYU years like? You were known as a brilliant writer and teacher, yet you left. Can you say something about that?

Darrell: Here’s what I’ll remember most about BYU: pals and a horde of young writers whose work was impressive and who have gone on to have great successes. There was a period of about five years when every graduate workshop I taught had two or three writers whose work was the kind that makes you sit back and say, “Here’s the real thing.” You simply try to get out of their way. These remarkable young writers kept coming year after year. Several of them went on to the University of Utah. Here I really don’t want to mention names because I’ll forget someone, and I don’t want to do that. But they’re writing and publishing novels; they’re writing movies.

At BYU, Bruce Jorgensen and I found one excuse or another to walk to the bookstore three or four times a week. I miss those days, our talks. Bruce is wise and kind and generous and funny—and he is one smart man. He introduced me to writers I needed to read. He was good company, and we all need that. He, as they say on the playground, schooled me. I’m grateful to him for his friendship.

So many brilliant teachers at BYU. That was nice of you to say I was known as one of them, but I wasn’t a brilliant teacher. I cared about what I was doing, but “cared” is one of those words like “sincere.” Sincere folk can be frightening and destructive in five or six different ways.

I chose to leave BYU. I needed to leave because I was uncomfortable teaching there. Felt that I was living a lie. By leaving I was trying to act with some integrity.

Douglas: What kind of writing schedule do you have? Do you work at writing every day? Are you a morning person? What kind of distractions can’t you tolerate? What does it take to get you started?

Darrell: What I’ll describe here is only an ideal, is what happens when all is going well, when the corn is as high as an elephant’s eye. I’m not a morning person, but that’s when I write. Teaching—the reading, the preparation, the responding to manuscripts, the classroom discussions, and workshops—fills up a day, usually seven days a week. When I was younger I often worked at teaching until one in the morning.

So, the ideal: During the afternoon and evening, I complete all the preparation for teaching so that, when the morning comes, I’m ready to write. I try to leave my desk clean. I often put my manuscript in the center of it. I get up, write for a couple of hours, go for a run (thinking about what I’m writing), return and do some more writing. At night, after I’ve finished preparing for classes, I read over what I wrote in the morning, scribbling on the manuscript. That means that when I wake up I’ve al ready begun the writing process: I need to type in the revisions I’ve made, so I’m already at work. The writing has already begun. There is momentum.

When the world is right, I work on short stories during the week and the novels on the weekend. Of course, that means I’ll be thinking about the novel all week long, making notes, writing down possible changes, asking questions.

The one lesson I have learned again and again and again: Get yourself to the place where you write. Put some words down. Don’t let anyone sit on your shoulder and say, “That’s bad. That’s not working. That’s dumb.” Write. Write poorly. Write well. Write. Something will come of your putting the words together. Italo Calvino calls it combinatorial play.

The only distraction I could not deal with was our dog Willie. No dog has ever barked like Willie. It was a matter of his timing. I would be working, and he would ask to go out, so I would open the door to the backyard. About the time I started to think it was going to be okay, about the time I was writing well, he’d bark. Once. Twice. At nothing. He might be staring at the fence. He might be studying the sky. He had his own rhythm, which was really no rhythm. Three barks. Sometimes, one. And I waited. Surely the one will be followed by more. No? Start to work. Then a seven-bark riff.

Douglas: What does the future hold for you in terms of writing? What are you working on now, and what future projects do you have in mind?

Darrell: I mentioned earlier that I’m polishing up a story collection titled So You Got Next to the Hammer and a novel titled Welcome to Wisdom, Utah. The collection opens with a novella, the title work, and closes with a novella I’m calling They Had Their Man for Breakfast. Sort of bookend novellas. The second one is a cut-down version of a novel I wrote about Las Vegas. It has to do with growing up there in the 1960s. The book will contain four or five short stories and three short shorts. There’s a certain kind of symmetry to it, but not to any purpose I can think of.

I’m excited about the novel I recently started, The Department of Big Thoughts. I mentioned that it is told by one of the characters in Bring Your Legs with You. The narrator of the novel is also the narrator of a story, “How Are You Going to Play This?” His name is Mac, but the other roofers have nicknamed him Spinoza. He talks big talk now and then. The book begins the day his girlfriend leaves him. He’s in his late forties, and she’s younger, probably in her thirties. The novel is set in Las Vegas.

Should take three or four years to finish. I probably ought to focus only on it, but I can’t stop writing stories.

Douglas: Las Vegas appears repeatedly in your writing. Why? What meaning does Las Vegas have for you, and the American West in general? Do you view yourself as a Western writer, and if so why? How important is it to live, write, and teach in the West?

Darrell: I wasn’t born in Las Vegas, but I grew up there. I was a baby when my family moved there. So it’s my context. Las Vegas frames the world for me. I’m not talking about Las Vegas as it now exists. Growing up I didn’t think Las Vegas was unusual. It defined reality for me. A Salt Lake City magazine asked me to write a piece about night, so I wrote about the showgirls coming to the grocery store where I worked when I was a kid. They came in full costume, complete with boas. I thought that was normal. Once I was talking to Francois Camoin about eating breakfast at Circus, Circus, while the aerialists above were swinging from trapeze to trapeze, doing their stunts. He said, “No wonder you write the way you do.”

A Western writer? No. Not really. I’m not trying to say something about living in the West. That assumes a sense for the big picture, which I don’t have.

I’ve been in Ohio for seven years now. I don’t live here the way I lived in the West. That’s a fact. After I was hired, I came to Athens to look for a house. I was on the porch of the one I eventually bought, and I said to the realtor, “I guess we’ll need to put in a sprinkling system.” She led me over to a spot out front and said, “You have drains in the lawn here.” I asked her where our property ended and the neighbor’s began. She said, “Your yard is where you mow to.” Winter came, and the sun retired. Next to the walkway to our place, there was a lamp that was light sensitive; it turned on at night and off when sunlight hit it. It stayed on for three weeks straight, day and night. The local newspaper advised us, after our first winter here, to walk slowly around the house and inspect for damage.

It’s a different world. We experienced our first ice storm. It knocked out the power. There was a fireplace in the dining room, so we put our bed in there. No heat, no light for three days. I learned how to build a fire. You need kindling, Kate told me. I thought, Kindling? I’d heard the word, but didn’t know what kindling was. A colleague loaned us firewood. In Ohio, I saw fireflies for the first time.

When we lived out West, we didn’t let the bed coverings touch the floor. Scorpions might climb up. As if you could stop them. You saw them high up on the ceilings.

Athens, Ohio, is built on clay. It shifts. The walls of your house crack. You adjust. You live in a certain way.

I don’t know if all of this comes through in stories. Where I live in Ohio is truly beautiful. Trees. Rivers. Those colorful small towns you see in black-white movies starring Spencer Tracy. I found a narrative point of view for One Mile Past Dangerous Curve that allowed the novel to both appreciate and wonder at the world here. The minute I found that voice the book took off.

But I’m not answering the question. Las Vegas—the wide hot streets I grew up on (we did actually fry eggs on them. We counted the number of steps it took to scoot across them in our bare feet), the desert I wandered in, the unreal round moons that sat on the city, Fremont Street (to this day I’m cursing the man who covered Fremont Street and turned it into The Fremont Experience or whatever it is they call it; he should be tarred, feathered, and ridden out of town).

I rode my bicycle all over the city. No fear. It was a safe place. Wide open. I think there were about 200,000 residents when I was in high school. There were The Strip people and townies. My friends’ dads ran casinos. They comped us tickets. I got to see the Rat Pack. My sister’s friend dragged her out to a motel on The Strip, knocked on the door, and Elvis answered. This was his first try at Las Vegas. They sat and talked.

There’s a frankness about Las Vegas. It’s tacky, and it knows it’s tacky. I recently wrote a review of a book written by Marc Cooper. Its title is The Last Honest Place in America: Paradise and Perdition in the New Las Vegas. What Cooper argues is that the city is honest about the fact that it wants your money. It’s upfront about what it is all about. I’ll go back to that word frankness. I want to capture that in my fiction.

You don’t want to get me started on how important it is for me to live, write, and teach in the West. I’ll end up begging for someone out there to hire me. I enjoy my job here at Ohio University. My colleagues are smart and funny and cultured. I’ve worked with students whose work dazzles me. Made pals.

But I do need the West. I miss the sky. I miss the way the day whitens in Nevada. I desperately miss driving through the desert.

Douglas: Any advice for the young fiction writer on how to get started, what to avoid and what to seek? How helpful is an MFA for the beginning writer? Does it serve an essential purpose if one doesn’t want to teach?

Darrell: My advice is cliched: read and write.

Don’t write in a void. Find the fiction that cares about itself and read it. There are writers who will make you want to write. Find them.

MFA programs, Ph.D. programs—essential purpose? Essential. What if, instead of sitting in your house writing, you’re sitting in a work’ shop and some writer says exactly what you need to hear? Sure, a program can help. But essential? I can’t answer that question.

For me, yes. I needed the University of Utah’s program. I was otherwise too ignorant. If nothing else, the program saved me ten years.

Douglas: You’ve never viewed yourself as a Mormon writer, but does your Mormonism signify in your writing in some ways?

Darrell: I was born into a Mormon family. There was a time when my father entered wholeheartedly into the religion. So I grew up as a Mor mon. It has to inform my writing, but I don’t think about it when I’m writing. Our growing up is present in whatever we write.

I don’t really write about Mormons, though there are Mormons in some of my stories. I don’t think about Mormon themes. I’m not interested in the religion as a subject.

John Bennion wrote an article about a few writers whose work in some way deals with Mormonism, the reference to which I unfortunately no longer remember. He spent some time talking about one of my stories—”The Glue That Binds Us”—from Our Secret’s Out, my second collection. The story is about a man who has married a Mormon woman. They’ve returned to Salt Lake City for a short visit. John compares the story to what he calls conventional Mormon texts, and he points out that what the story resists is any kind of easy connection between signified and signifier. John argues well—I’m a reader here, not the writer—and soundly that the story doesn’t so much undermine Mormon thought and culture as it simply won’t settle into the kind of thinking or worldview that Mor mons and most Mormon fiction easily accept. It doesn’t attack Mormonism, but it won’t let Mormonism capture the narrative. John is kind to point out that my work does not make judgments or pronouncements. I like to think that Mormons are present in the story the way they are present in the world.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue