Articles/Essays – Volume 38, No. 1

Reed Smoot and the Twentieth-Century Transformation of Mormonism | Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle

On June 23, 2004, LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor that the United States can bestow, at a White House ceremony presided over by the president of the United States, who described Hinckley as a “wise and patriotic man.”[1]

The Hinckley honor came just one hundred years after a very different appearance of the LDS Church president in Washington, D.C. On March 2, 1904, President Joseph F. Smith, in response to a subpoena, began a week of testimony before the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections on the issue of whether Mormon Apostle Reed Smoot should be seated as a member of the Senate from Utah. Smith was questioned by hostile senators about whether a member of the Church leadership or even a member of the Church could truthfully swear allegiance to the United States and truthfully take the oath to serve as a member of the Senate.

If the Smoot controversy had been resolved differently, Hinckley may not have been honored at the White House and the Church over which he presides likely would be a far different institution than it is today. In many regards, the Smoot controversy was the most critical event in the transformation of the LDS Church during the twentieth century.

In a nutshell, the Mormon accommodation with the U.S. government worked out at the end of the nineteenth century was this: The Church was to give up polygamy, which was ostensibly the purpose of the 1890 Manifesto issued by then-Church President Wilford Woodruff; the Mormon political party was dissolved and Church members were divided between the Democratic and Republican parties in 1893; and in return, Utah was admitted to full statehood in 1896.

By the time Apostle Reed Smoot was elected to represent Utah in the U.S. Senate in 1902, serious questions were being raised in Washington about whether the LDS Church was keeping its part of the bargain. A decade and a half after the Manifesto, at least four members of the Quorum of the Twelve were still advocating and performing polygamous marriages. Protestant evangelizers in Utah were convinced that the Church had not, in fact, abandoned polygamy.

B. H. Roberts had been elected Utah’s representative in Congress in 1898. He was a practicing polygamist who had served time in prison for violating federal anti-polygamy statutes, and he was a member of the Church’s First Council of the Seventy. After extensive hearings and debate, the U.S. House of Representatives refused to seat Roberts. Four years later, Smoot was elected to the Senate. He held an even higher position in the Church hierarchy, though he did not practice polygamy. His election provoked a coalition of mainstream Protestant groups to launch a massive national campaign which generated millions of signatures on petitions demanding that Smoot not be seated.

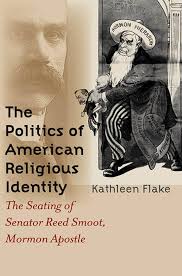

The best and most comprehensive study of the nearly four years of hearings and debate on the seating of Smoot is Kathleen Flake’s recently published The Politics of American Religious Identity. Most studies of the Smoot affair have viewed it in the narrower LDS context as the culmination of the Mormon effort to be accepted into the American political and social mainstream. Flake places the Smoot controversy in its broader social, political, and religious context—both in the wider national context and in the context of the internal Mormon transformation taking place at that time.

For Latter-day Saints, Flake provides significant insights into the internal response of the Church to the Smoot hearings as they proceeded. While Joseph F. Smith was intent on having Smoot in the U.S. Senate, he initially was reluctant to take the steps essential to assure his seating. The first response was a statement without real action. Just three weeks after returning from testifying before the Senate Committee in Washington, D.C., Smith issued the declaration known as the “Second Manifesto” at the April 1904 general conference. He affirmed that post-Manifesto marriages were prohibited and stated that the violation of that prohibition by members or officers of the Church would result in discipline, up to and including excommunication.

Yet the Second Manifesto was followed by an unwillingness to act decisively. Smith apparently hoped that public statements would be adequate and that pressure for real change would dissipate. He was unwilling to press the Quorum of the Twelve to require the removal of John W Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley, two members of the Quorum involved in post-Manifesto polygamy. Furthermore, these two apostles refused to honor subpoenas to appear before the Senate Committee. Smith’s strategy did not work. Pressure in Washington did not subside. Legislation gravely damaging to the Church was seriously being considered and it appeared that Smoot would be denied his Senate seat.

The disarray within the hierarchy was publicly evident. Smoot, sitting on the stand in the Tabernacle during October 1905 general conference, publicly refused to sustain his own quorum because of its refusal to take action against Tay lor and Cowley. Finally in April 1906, three new members of the quorum were sustained, replacing Taylor and Cowley, who had been dropped from the quorum, and the deceased Marriner W. Merrill, who also was involved in post-Manifesto polygamy. All three new apostles were monogamous.[2]

One of Flake’s most interesting chapters focuses on how Church leaders faced the problems of Church members trying to cope with the changes required to resolve the Smoot controversy. For half a century, the Church had largely defined itself in terms of conflict with the U.S. government over plural marriage. In the midst of the Smoot hearings, the centennial of Joseph Smith’s birth provided the opportunity to refocus key beliefs and values in the new post-polygamy Church by emphasizing the early visions of Joseph Smith. Flake’s discussion of this religious redefinition is particularly significant.

Another important contribution is Flake’s analysis of the broader American political, social, and religious background to the conflict. She discusses the social and religious changes taking place in American Protestantism at the turn of the twentieth century which provided the opportunity for resolving Mormon-American relationships. She also provides an interesting political and economic perspective on how political leaders in the Progressive Era may have seen Mormon ism and monopolies in a similar light and found them subject to similar types of “regulation.” She also gives an excellent review of the national political context to the Smoot issue.

The inclusion of photographs and political cartoons from the era give the book a delightful flavor of the time. In providing sources for many of the newspaper clippings and cartoons, however, the book makes consistent but incorrect reference to the “Howard” B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University. Other than that error, the sources and citations are carefully done.

Ironically, the success of the transformation of Mormonism that followed the resolution of the Smoot affair came full circle in the abrupt end of Smoot’s political career in 1932. In 1903, the Washington establishment was particularly concerned that the Church leadership apparently enjoyed the unquestioned loyalty of Mor mons in nonreligious as well as religious matters. In 1932 Smoot, still a senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve, ran for reelection as he had ever’ six years since 1902. There could be no stronger statement of the Church leaderships support for Smoot’s candidacy than the fact that he was seeking reelection again. He lost, even though Mormons made up the majority of Utah’s voters.[3] The Church had become a mainstream religious organization, and the spiritual convictions and political loyalties of its members were separate.

There is another ironic indication of the success of the Church’s transformation during the last century. The Smoot controversy focused on Mormon marriage practices as being radically outside the mainstream of American social values. A century ago during the Smoot hearings, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was a leading voice calling for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to give Congress authority to regulate marriage and define marriage as only the union between one man and one woman, in order to outlaw the Mormon practice of polygamy.[4] Today, a century later, an effort to amend the U.S. Constitution led by President George W. Bush seeks a Constitutional amendment similarly to define marriage as only the union of one man and one woman. In the Roosevelt era, the effort was directed against the LDS Church. Today the effort is directed against same-sex marriage, and the LDS Church is one of the staunchest allies in supporting the most conservative social values.

Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 238 pp.

[1] “President Bush Presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom,” June 23, 2004, White House webpage, http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/re leases/2004/06/20040623-8.html.

[2] One of the three was David O. McKay who later served as Church president (1951-70). The need to find monogamous leaders was probably important in his selection at this point. His family was not part of the Church leadership and thus had not been pressed to participate in plural marriage.

[3] Smoot, the Republican candidate, was defeated by Elbert D. Thomas, a Democrat and faithful member of the Church who was a political science professor at the University of Utah.

[4] In his 1906 State of the Union Address to Congress, President Roosevelt expressed strong support for a Constitutional amendment on marriage: “I am well aware of how difficult it is to pass a constitutional amendment. Nevertheless in my judgment the whole question of marriage and divorce should be relegated to the authority of the National Congress…. In particular it would be good because it would confer on the Congress the power at once to deal radically and efficiently with polygamy. .. . It is neither safe nor proper to leave the question of polygamy to be dealt with by the several States. Power to deal with it should be conferred on the National Government” Theodore Roosevelt, “Sixth Annual Message to Congress,” December 3, 1906. Retrieved in October 2004 from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showdoc.php?id=749&type=lckpresidenf=26.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue