Articles/Essays – Volume 36, No. 3

My Short Happy Life with Exponent II

Sometimes an occurrence turns out to be more than all involved ever expected it to be. The stone drops into the water and the widening rings reach all the way to the lake’s edge. A little thing that happens in someone’s living room gets discussed at the far edge of the continent. The things done on the side of much more important things turn out to be the most important after all. Small creative enterprises grow and develop lives of their own.

Such were the results of the work of a few LDS wives and single students back in the 1970s. Under their own auspices, they gathered to do a few little Relief Society-type projects, the sort of thing they were quite experienced in doing, that they had been doing for years with little particular attention. They didn’t think that that much was really happening, but they did work together as they had previously, and what is interesting, they began a run of activity which continues to this day, more than a quarter of a century later.

Exponent II was born in one of those times when the world turned upside down. Having been through a pretty significant civil rights revolution, the nation was ignited by other discontents. A serious anti-war movement was under way and along with it, a feminist revolution. The war in Viet Nam, and other social tensions, had aroused opposition from many student groups. Women, who had been the silent majority, the obedient secondary partners, the statues on pedestals who descended to rock the wailing infants and scrub the floors, began to test their ability to do more.

My husband and I experienced first hand several of these incidents. In 1968, Richard received the Bancroft Prize for writing a history book published the year before. This meant that we traveled from Utah to New York City to attend the awards ceremony at Columbia University.The prize was awarded at a dinner for three or four hundred people, a black tie-long gown affair with a receiving line. My hair was done up. Men kissed my hand. Everyone seemed cultivated and charming. The winners gave erudite and witty speeches. The elite, Ivy League event was as close to Versailles as I have ever come, and was certainly a long way from Provo.

By the time we arrived back in Utah, Low Library, the elegant building in which the prize ceremony had been held, was occupied by insurgents. Students made demands. The administration fell. The police were called. Columbia entered a dark period from which it only emerged many years later. We arrived in Boston that fall of 1968, just in time for the occupations at Harvard. The world had turned upside down.

We were moving to Arlington, Massachusetts, for a fellowship and a year-long sabbatical. We had lived in Boston before. Richard had studied at Harvard College and also served a mission there. I’d gone to Wellesley College and met him on a visit to Cambridge while he was still on his mission. When he returned as a student again, we began to keep company and were married after his graduation and my junior year. We stayed on as he became a graduate student and I became a housewife and mother, leaving a few years later to live in Provo where he taught at BYU. Now in 1968, we had come back for yet another New England tour.

However, Richard’s Bancroft Prize suddenly made him a hot commodity, and he was heavily recruited, particularly to accept an appointment at Boston University to establish the new American Studies graduate program. He wrestled with this decision, finally agreeing to take the job. As for me, I was in favor of the move from the beginning. I’d been happy enough in Provo, but I saw more opportunity in Boston. After marriage, I had completed my A.B. degree in English literature. Although my family would have been quite happy if I had dropped out of school, I liked to finish things up. I graduated in maternity clothes, and our first child was born that fall. I planned to be the Mormon mother I had been socialized to be. But by the time my daughter was just a few months old, I was hungry to get back to school. I took a few night school courses, and when we moved to Provo, I applied to a master’s program to study American literature. I started the program with two small children and finished up with three. This MA later made it possible for me to teach freshman composition at Rhode Island College during one of our stays back east. While I taught there, our fourth child was born, and I continued to teach the course at BYU when we returned. But when I told the chairman of the department that I was expecting number five, he ruled that I could no longer teach freshman English.

What to do? I needed something to think about when I scrubbed floors, but there was no doctoral program in English. I explored working toward a teaching credential, but that entailed taking all my courses over again with more attention to pedagogy, which I was unwilling to do. I was, as I have been many times in my life, just stymied. I began to take random courses again, but I wished I could be in some program where I could feel myself moving forward, no matter how slowly, toward a worthwhile goal.

But what could I have been thinking? What did school mean to me, a Californian who had always been more interested in fashion and the future than in the past filed in dusty old books in libraries. Why did I feel driven to do this? I cannot remember why I was so sure that I needed to work for a Ph.D. Part of it was doubtless the respect paid to the life of the mind in that New England neighborhood. Part of it was that I couldn’t just get some job that would compete with caring for all my little children. Richard and I felt very strongly about leaving our children then. Baby sitters and day-care were unthinkable choices. But I did feel that I had to do something. I remember a beautiful autumn Saturday in Cambridge in Harvard’s Memorial Hall. I had come to take the Graduate Record Exam, spending a full day at critical reading and multiple choice. It was the day of the Harvard-Yale game, and as I left the hall to walk to my bus stop, I encountered throngs of happy fans. For years I had attended home games, but here I was, choosing to take a miserable examination instead. What was wrong with me?

Richard’s new connection to Boston University brought reduced tuition for me and also an easy admittance to the doctoral program in English, even though part-time students, of which I was one, were seriously discouraged, and the chairman was openly scornful. He was constantly disgusted with me, the little housewife. Doctoral work was to be difficult, conducted in the time-honored way in which the faculty themselves had suffered through their studies. He had a right to be tough with his students. An English doctorate required four languages. I had French and Old English from my MA studies, and I began to study Latin with plans to do German later on, amused by the idea that I moved from cooking meals and sewing buttons to learning tenses and vocabulary.

I should also say that one of my motivations was to escape the competitions that Mormon housewives engaged in. We were all locked into being the best mother and wife with the most impressive children, in the cleanest house, serving the most beautiful and nutritious meals, etc. etc. I was willing enough to do those things, but rebelled at the effort required to be the best. I rebelled against the miserable old belief that any job worth doing was worth doing well and that these exercises, which must be repeated constantly, must be accorded such dedication. I wanted to be so busy with other things that I could not make a life’s work out of household chores, even though I enjoyed many of them.

Still, Latin! And putting up with the sanctimonious English chair. Was it worth it? One day Richard came home from a meeting of the American Studies committee. He described the discussion of the language requirement. The group had decided that they could see no reason to require any more than a single foreign language. Lightbulb! His off hand conversation changed my life. I saw a little distance open ahead. I withdrew from the England department and enrolled in the American Studies program before it was even up and running—as the first student. Admittance was no problem under the circumstances.

All this is prelude to the important events that followed, as is another event in Cambridge which had preceded our arrival. Back in the old days, LDS congregations were expected to contribute and raise money to build and maintain their chapels. The church contributed forty and later eighty percent of the cost, but large amounts of money had to be raised locally, and this came on top of tithing, fast offerings, welfare, missionary fund, and a number of other obligations. The Cambridge Ward had a very nice building, erected through the sacrifice of many poor members and the contributions of many former members. But more money was always needed, and this was a congregation of promising but still cash-starved students and other members equally hard up, who were always looking for money-raising schemes. One evening at a dinner-party, the bishop, Bert van Uitert, suggested some possible money raising projects. One promising idea was a guidebook to Boston and its environs. He saw a market for this book and the possibility of significant income. The Harvard Business School students in the group considered the idea, but decided it would be just too much work. Bonnie Home, speaking for the women, said that the Relief Society would take it on.

That is how A Beginner’s Boston came to be written. “A friendly hub handbook containing information helpful to tourists, new settlers, students, bird watchers, bargain hunters, music lovers, walkers. . .” was a Relief Society project written in the sprightly prose of “chairman” Laurel Ulrich with the fabulous illustrations of Carolyn Peters (now Carolyn Person). The book relied on the experience and research of lots and lots of sisters—and a few husbands—to turn out what the Boston Globe called “A thorough, wonderfully readable & practical guide to just about everything in and around Boston.” The book went through several editions from 1966 onward and made thousands of dollars for church activities. The sisters worked together toward commercial success, transcending the boundaries of the ward and church.

As I hope is clear, this was a time of turbulence, even for LDS student housewives generally considered a group caught in the time warp of conservative living. Even they were aware of the movement of the times. In 1970 Laurel suggested that we should get together and talk about our lives as Mormon women, and she invited a dozen or so women over to her house for a discussion. I don’t remember whether she called it a consciousness raising group, which is what such regularly-meeting cells of women were called in those days. As I recall, we gathered and talked for a couple of morning hours, had some refreshments, and quit before lunch. These were unstructured meetings, no officers, no minutes, no official plan. At the end of each meeting, we would schedule another. The meetings took place every few weeks, moving from one house to another. I can’t remember how long this went on.

There were no real ground rules, and the discussion moved freely. As I recall, the major topics of conversation dealt with housework and its unending toll, with childbirth—was there a limit to how many children we should have? Should birth control—then somewhat forbidden-be used? And were we obligated to take on any and all church jobs we were requested to take? This sounds like a pretty tame feminist agenda, but these issues concerned us. Our two single students Judi Rasmussen (later Dushku) and Cheryll Lynn (later May) introduced some feminist books and ideas. And people were reading Kate Millett and other noted writers. We did not agree on many topics. No holds were barred in the discussions and considerable heat, light, rage, and pain emerged. I considered myself a voice of moderation and wisdom at the meetings, but I would go home and give my husband the strongest possible arguments for change. We were all exploring the ways in which we thought about women’s roles, and we moved from one extreme of reaction to the other in our discussions. We came head to head on some issues. During the healthy give and take we confessed, discussed, and argued our views, and sometimes went home with headaches.

Out of this exchange emerged Dialogue’s “pink issue,” published in the summer of 1971. I have heard people postulate why this group was called on to do a women’s issue of the journal, that it was because of A Be ginner’s Boston or because we had some organization or so much under employed brain power. But the truth is that we asked. Gene England, then Dialogue’s editor and a longtime friend, was visiting us. One evening as we walked through Harvard Yard, I suggested that there should be a women’s issue and that we should edit it. I told him about our group, and he hesitated not at all. We were empowered to turn out an issue.

None of us had any experience in this kind of thing. We were totally in the dark. But we solicited manuscripts individually and with an ad in the journal and began to gather materials. We wanted to feature our local people, but did not want to dominate the issue. Our discussions at meetings moved to a discussion of the things to include in the issue and encouragement for some of our people to write them. There was a great deal of individual support and encouragement. We looked at a lot of stuff and agreed to take some very strange things. It was a tremendous amount of work, but we finally completed our issue. We referred to it from time to time as “Ladies’ Home Dialogue.”

By the time we submitted our materials, Gene England was no longer the editor of Dialogue. Robert Rees was in charge. He was less than enchanted with this legacy issue; he did not approve of the con tents. He really did not want to publish them, but he did. Eventually the “pink” issue of Dialogue came out and became something of a sensation. People seemed to be amazed that there was something to say about the female aspect of humanity and that we had done it.

The pink issue included contributions from twenty-five women and three men. Another eight women were credited for significant help. The introduction included this description of the group: “The original dozen or so are women in their thirties, college-educated with some graduate degrees, mostly city-bred, the wives of professional men and the mothers of several children.” (A footnote lists the average number of children at three and two thirds each. “Of the four children born to group members this year, one increased the family’s children to five, one to six and one to eight.”) “While this group remains, we have added another dozen or so, including several young professional wives without children and some singles.” The issue made an early appeal for the acceptance of diversity within our own ranks and asked, “Does it undercut the celestial dream to admit that there are occasional Japanese beetles in the roses covering our cottages?”

Rees, in his objections to the material, thought that we had not dealt with the real issues of Mormon women. I remember my husband saying that he thought Rees was presumptuous to tell us what the issues for Mormon women were. But if they weren’t church service or birth control or housecleaning, what were they? Bob’s answer was priesthood and polygamy, historical LDS issues. I was stung by this revelation. Those were not our issues; we occasionally discussed modern feminism, but we didn’t have much to say about pioneer women. Could we have completely missed the point? Had we failed to comprehend our own lives as LDS women?

Rees’s critique, however, soon bore fruit. About this time Susan Kohler discovered the Woman’s Exponent, the Utah periodical published from 1872-1914, stored in bound volumes at the Widener Library. This was amazing to us. We were all life-long Mormons, but not a one of us had ever heard of this journal. Though not an official publication, the magazine included Relief Society news along with suffrage news, information about women the world over, and charming local stuff. Harvard University had a complete run of this fascinating periodical, and I remember spending an afternoon at Widener, copying out humorous news and poems to make up the program for one of our ward Relief Society birthday parties. The discovery of the Woman’s Exponent opened a new life to us LDS women with college degrees. The journal, along with Robert Rees’s comment, launched us into a study of our past. With the Exponent as our easy entree, our discussions became historical and comparative. We got books out of the library. We talked about our ancestors and discovered the strongly feminist past of LDS women.

While we were moving into the past, someone suggested that we should hold an annual dinner. Some of our women such as Bonnie Home and Mimu Sloan were more than gifted at organizing food for large numbers of people. We could, we thought, show off this other aspect of women’s work by inviting in people sympathetic to our interests and willing to pay for dinner. We would also feature an important female speaker, thus allowing us to honor her and to get to know her. Maureen Ursenbach Beecher was our first speaker. She was followed in subsequent years by Juanita Brooks, Lela Coons, Emma Lou Thane, and other women we considered to be role models in various ways. This Exponent Day dinner was another of the ways that the group made something out of nothing. Our unpaid labor created value.

At this first dinner, Jill Mulvay (Derr), then a public school teacher, approached Maureen, a researcher and writer in the church’s Historical Department, and asked how a person could get a job like that. Maureen invited her to the office when she was next in Salt Lake, and Jill became part of what eventually became the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for LDS Church History now located at BYU. She has, in fact, been the director for some months now.

This kind of interaction shows how the church was operating back in those heady days. Maureen worked for Leonard Arrington, the first and only professional historian to run the church history operation. Leonard was a powerful bridge builder and motivator. Under his encouragement and direction, hundreds of people began and completed church history projects. He had organized the Mormon History Association, which brought about a rapprochement between historians of the LDS and RLDS churches, and he supervised a network of everything being done. When my husband returned home from an MHA meeting one time, he told me that he had had a long talk with Leonard about things I was doing at graduate school and with the women in Boston. I was amazed that someone of such importance could be interested in me or our small enterprises. But the next week I received a long letter from Leonard, following up the conversation, telling me what other people were doing, suggesting sources, and offering help of various kinds, from copying documents to providing modest funds to help with research. All too amazing. Thus, we were drawn into the great LDS history network.

Our historical discussions led to our next big project, a weekly class for the local LDS Institute. Judy Gilliland, one of our sisters, was married to Steve Gilliland, the institute leader. She suggested that we could probably do an institute class, and Steve did invite us to do one. The members of our stable but ever-shifting group signed up to research and prepare papers for presentation. Each chose a topic, some individual people, some historical events, some ideas, and then began to work. The women eagerly began trekking to Widener Library in Harvard Yard and the Boston Public Library to research such subjects as Mormon women in politics, in medicine, in literature, in polygamous relationships, and so on. There were some serious topic-shifts along the way. I began to look for conversion stories, for instance, but not finding what I wanted there, I moved to miraculous cures. That topic seemed to include too much folklore, so I moved on to the way women administered healing powers over the years. Others made similar migrations. Still, we managed to come up with a varied and complementary list of topics which we advertised and presented as “Roots and Fruits of Mormon Women,” a title I much prefer to the more sentimental and common designations of “roots and wings.” The class was very successful, presenting new information to all of us and to an audience of fifty or so each week. We decided to get the presentations into shape as papers for publication.

I must say at this point—and could easily say at many points—how heady an experience this all was. We were just little housewives, but we became very arrogant little housewives. Although smart enough and able enough to do many things, we defined our husbands’ work as of the truest family importance. Yet here we all were, working together, engaged in frontline enterprises, researching, thinking and writing for ourselves. We were publishing to an audience interested in reading what we had to say. We were making public presentations to people who came to hear us. This was more empowering than any successful women today will ever be able to imagine. We felt invincible.

I spent a lot of time working on the essays for the Roots and Fruits book, editing, checking footnotes, retyping, choosing pictures, working on a time-line and suggested reading lists. I had never done this work before, so I was surprised at how hard it was and how much of it there was to do. Some essays fell through, and to fill out the contents, Leonard suggested that we add essays from people working for the Historical Department: one from Maureen on Eliza R. Snow, one from Jill on school teachers, and one from Christine Rigby Arrington on early doctors. Working on this book along with my doctoral work, not to even mention keeping my household running and my family dressed and fed, was a fair amount of work. But a press had asked for the Mormon book, and I wanted to get that done and submitted. Meanwhile at the meetings, we were looking for new challenges. What else could we do?

At one meeting, in response to this concern, I said that my husband thought we might begin a newspaper, something like the Woman’s Exponent, perhaps. This idea was greeted with enthusiasm. Yes, of course, it was what we were born to do. The notion had some practical promise, too, because we had a journalist in our group, Stephanie Smith Goodson. She had actually been paid to be a reporter in the past. None of the rest of us had even been on our high school or college newspaper or yearbook staffs. We would be total neophytes at such work. Stephanie was willing to do it, but she was overworked with a new baby and a calling as president of the ward Relief Society. She decided to ask for a release from the latter heavy-duty assignment so that she could do the newspaper. However, despite tears and entreaties, the bishop refused such a release. She concluded she could not take the job.

So Carrel Sheldon, who despite having several small and demanding children to care for, was a major mover and shaker in all our operations, told me that I would just have to be editor. I was willing enough, but already more than a little busy with other jobs. Couldn’t we just wait until the book manuscript was completed and submitted? No, said Carrel. We have to begin right now. And so we did.

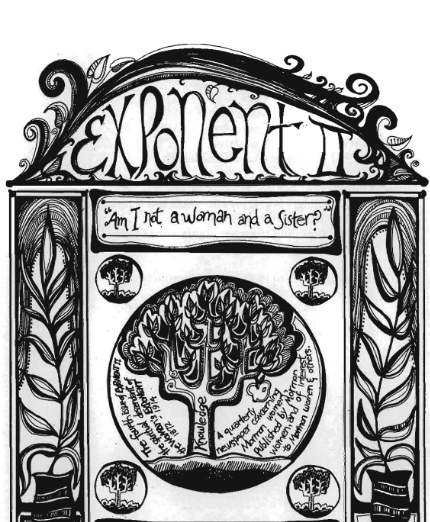

To start a newspaper that, in its own way, picked up where the Woman’s Exponent had left off seemed the thing to do. It also seemed appropriate to indicate that heritage in the new title. So the name Exponent II was chosen to symbolize the historical link, and the first issue, which came out in July of 1974, proclaimed the newspaper to be “the spiritual descendant of the Woman’s Exponent.”

We aimed for some diffidence, calling it a “modest but sincere news paper.” Maybe more notable, we set out to bridge the gap between the church’s paradigms and our actual lives as women. “Exponent II, posed on the dual platforms of Mormonism and Feminism, has two aims: to strengthen the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and to encourage and develop the talents of Mormon women. That these aims are consistent we intend to show by our pages and our lives.” That old editorial still has a ring.

Once we had managed to get the first issue’s content somewhat complete, it went to Susan Kohler, our compositor. Of course this was prior to the days of computers. What Susan had was her husband’s office IBM Selectric typewriter with its ball of type and its automatic return. This was state-of-the-art, and Susan could use it after the office was closed for the day. There was no neat way to correct errors, so when errors occurred, she would just begin the line over again and type it correctly. This meant that she brought in piles of text shredded like spaghetti which had to be arranged properly and pasted together.

Carrel Sheldon set up the financial accounting, helped create and mail out advertising flyers, and managed the subscription database, which at that time had to be typed on keypunch cards at MIT. Paste-up took place in Carrel’s living room, Diane McKinney’s kitchen, and Grethe Petersen’s attic, among other places. On those long and busy evenings, the pages were composed on a light board that Carrel’s husband Garret had constructed for that purpose. Almost everyone had children, and many of them were present, wandering around carrying blankets and bottles. Anyone who wanted to could paste up a page, which included some design work. Strips of typewritten paper were literally pasted onto large sheets of blue-lined graph paper.

A succession of art editors—Carolyn Person, Joyce Campbell, Sharon Miller, Renee Tietjen, Linda Hoffman, to name a few of the early ones—would sketch an initial layout, letterpress titles, and then insert photographs or artwork that they had created themselves or solicited from other artists. After completing a page, a staff member signed off on it, and it was then hung on the wall to be proofread by editors Claudia Bushman, Nancy Dredge, and Susan Howe (later editors were Sue Booth Forbes and Jenny Atkinson). I was usually around to proofread, but the pages looked so good I couldn’t find mistakes even when they were there. I once let through a story of Bruce Jorgenson’s in which the sections had been pasted up in the wrong order. The story line was wrong, but it was such a lyrical, lofty piece that it still sounded good. I didn’t even see the problem until I received an anguished letter from Bruce.

When the paste-up was completed and the whole had been sort of proof-read, Carrel took it to the printer, and we had a few days reprieve before we had to get together again to mail it out. The first printing was managed with money Leonard Arrington had sent us for research purposes. I think it was $250. But because we were all so thrifty, we had just absorbed most of our own costs. Here was this nice little knot of seed money. We printed and sent out the first edition for free to everyone we could think of, soliciting subscriptions for future issues. We sent multiple copies to our best connections to give out to potential subscribers. By the end of the first year we had a subscription base of 4,000 readers.

I had worried that if we used everything we had for our first edition, we wouldn’t have anything left for the next one. But happily I discovered the law that new material is generated by using up what you have. Since that early experience I now clear the decks for every project, knowing that there will always be plenty more ahead.

Seeing our labors come back in print, an actual, tangible product, was the most exciting moment of all. The group would then hold a huge mailing party where the papers were sorted by zip code, labels were attached, and bundles were bound according to the post office’s regulations for third class mail. The mailing, which Susan Kohler supervised in the early days, was a huge job. Besides the work, unfriendly post office officials would say cross things.

By the fourth issue, which was fronted by Carolyn’s provocative tree of knowledge, from which hung a large and luscious apple, things were settling down somewhat with people taking on specific jobs. While some did more work than others, everybody still did everything. Stephanie Goodson was doing some editorial work; Laurel Ulrich was doing book reviews; Heather Cannon was selecting features for “Cottage Industry”; Patricia Butler was writing the “Frugal Housewife”; Sue Booth-Forbes was doing sports; and Judi Dushku had begun her popular long-time feature, “The Sisters Speak,” where women wrote in to answer the question of the issue. Business people also had editorial assignments. So it was that Susan Kohler, assisted by Vicki Clarke, tended the mailbox, recorded subscriptions, and corresponded about business matters as well as scouring the old Woman’s Exponent for choice bits to reprint. Carrel Sheldon, assisted by Saundy Buys, was typing the whole newspaper by then—generally with a baby on her lap—also writing articles and housing the operation in her big house. Joyce Campbell, then art chair man with the help of Carolyn Person, also made decisions about the poetry. Connie Cannon, historian and secretary, also commissioned and wrote profiles. Bonnie Home supervised the layout after choosing the Letters to the Editor.

Somewhere along in here, we decided we needed to have a picture taken of the core group of women involved, which then included Joyce Campbell, Connie Cannon, Heather Cannon, Judi Dushku, Stephanie Goodson, Bonnie Home, Susan Kohler, Maryann MacMurray, Grethe Peterson, Carrel Sheldon, Mimmu Sloan, and me. I think Heather Cannon’s sister, a good photographer, was available to take the photograph. Once again we went to Harvard Yard, this time to the bronze John Harvard himself, all wearing long skirts—except Carrel who had not gotten the message. We disported ourselves around him, posing for several photos there and on the steps of Widener Library. Some student passing by wondered who we were. His friend responded that we “looked like a bunch of Mormons,” no doubt meant as a slight. And I suppose that compared to other feminists of the time, we did seem to be a pretty bland, wholesome crew.

There was yet another significant innovation by the Boston sisters, the Retreat. I was against the name from the beginning. It was true that we would “retreat” from our responsibilities for a day or two, but the term was not part of our tradition. What I thought the event should be called was the Revival. That term was as true as the other and basic to our history. But I lost that argument. We organized and headed off for weekend Retreats from the very early days on, and Exponent II still Re treats annually to this day.

When the “Roots and Fruits of Mormon Women” manuscript was finally completed, I sent it off to the publisher. The book’s name had by then been changed to “Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah.” Lots of people thought the former name was too flip. The manuscript had scarcely gone out, when it was returned. The publisher did not like it. Many years later I discovered that he had sent it to another LDS female author for comment, and she had found it wanting. This was quite a blow, since we had grown quite used to success. We did not receive any suggestions or criticism, just a refusal. We offered it to other publishers, who also turned it down. One said that it “was too hot to handle.” He wouldn’t touch it “with a ten-foot pole.” I put the manuscript away, a painful reminder of many wasted hours, and continued with other chores.

At this point, Carrel Sheldon rallied and decided that the book really had to be published. And that because no one else would publish it, we should publish it ourselves. This required that we set up our own publishing company, which we did and called Emmeline Press, as a tribute to longtime Woman’s Exponent editor Emmeline B. Wells. We were once again moving into uncharted waters. Jim Cannon, the husband of Connie Cannon, one of our members, practiced law in Boston. He willingly undertook our legal work on a pro bono basis. Under his direction we got a waiver of any involvement in our manuscript by the first publisher. We set up a corporation as Mormon Sisters Inc., although later the church insisted that we change the name, and we became Exponent II, Inc.

All this meant that we needed money. Carrel found us a printer. We showed him the manuscript and set the specifications, opting for large type, lots of pictures, and a good looking product. When the printer gave us a bid, Carrel went to the bank and negotiated a loan. Twelve of us became limited partners for the loan, each responsible for just her own share. Carrel borrowed the cost of doing the book plus the interest on the loan. As we signed the papers, I was overcome with gloom. Would this mean disaster? Although the amounts look minuscule now, going into debt for my own selfish purposes seemed frivolous, against all my instincts. Maybe this time we really were biting off too much. But others seemed confident enough, so we moved forward.

Nancy Dredge went to work for the publisher, typing up the manuscript with all the codes that had to be entered for the typesetter. Carrel ordered 5,000 paperback books and 1,000 hardcover. But, again showing how well all of our enterprises worked together, we had the newspaper subscription list, a very choice mailing list of people likely to be interested in our book. The book went to press in the fall of 1976. The paperback book cost just $4.95, and we advertised it as a Christmas gift, selling multiple copies to our friends. Before the books were even delivered to us for transshipment, we had the money to repay the loan. We dedicated the book to our true friend Leonard J. Arrington, saying, “He takes us seriously.” Another blazing success. As of 2003, the book is in print and available from its third publisher, Utah State University Press.

We felt we had discovered valuable information about the history of LDS women that all would welcome and benefit from. Who knew that Utah women had begun to vote in 1870, fifty years before U.S. women got the franchise? Who knew about the promising LDS female doctors who brought medicine to the West and taught Utah women to care for themselves? And yes, weren’t those early Mormon women strong and impressive? We felt like missionaries sharing the good news. If our newspaper was a descendant of the Woman’s Exponent, our book dealt with women from whom we were spiritually and sometimes physically descended. We felt in some ways that getting this book together, polished, edited, financed, and finally published had been a trial equivalent to crossing the plains. “The authors feel that they have made history by making history,” said the introduction. Critics would discount this “self-congratulatory” statement.

The newspaper continued to move along well. One of the things we did was to address and send copies of an issue to the church office building, addressed to all the wives of general authorities in care of their husbands. This was done with the best will in the world. We were sure that they would want to know about the paper. We certainly did not expect our little periodical to offend anyone. Yet to our consternation, we were sternly informed by some that our paper was not welcome and that we were never to send it again. This was one of several negative reactions. Sometimes we were written up in other secular newspapers and came off sounding a little shrill. These articles were sent to Salt Lake City and got some negative attention. When we invited local women in greater Boston to join us, many did not wish to. And some of these women who did not want to join us were offended by the paper’s very existence. Several anonymous letters complaining about our elitism and questionable activities made their way to Salt Lake City from our own wards and were then forwarded back to us. Alas, all very painful.

At this time my husband was serving as stake president in Boston, and we frequently had visitors from Salt Lake City, who came out to address our stake conferences. Many of these visitors had been our friends at one place or another, and they often stayed with us in our shabby old Victorian mansion. One such visitor warned me that Exponent II would come to no good end and that it must be discontinued. I remember responding in great surprise that the church had nothing to fear from me. He said specifically that being involved with the paper would “damage us in the eyes of the church.” He was also concerned that the stake president’s wife was involved in such an enterprise. His concerns about the paper were not about what it was, but about what it could and would become. He said he felt very bad about having to tell us these things. I thought about his counsel for the coming week and decided, finally, that I would have to go along with his advice.

The next weekend we had a retreat at Grethe Petersen’s beach house. At the meeting in the evening when we were sitting around talking, I told everyone about my experience and how I feared that we were getting deep into trouble and had better quit. This news was greeted with disbelief and sorrow. I said I was unrepentant, but I was obedient. In the long discussion that followed, many alternatives were suggested. The conclusion was that all involved should write letters to that authority explaining the benefits of the paper and of all our other activities, telling how they had led to increased sisterhood, how our testimonies had grown, how broken-hearted we would be to part with the paper and so on. I had already committed myself to withdrawing from the enterprise and so did not write a letter.

When the letters were delivered in Salt Lake City, the authority who had visited us talked to L. Tom Perry, who had been our stake president and knew us all. The first man said that he thought that the letters deserve a response and asked Perry if he would go to Boston and talk to us, which he did. He spent the flight from Salt Lake City reading all the issues published so far, and he admitted that he found nothing objectionable in them. But again, there was the fear of what the paper would become. He said that it was not suitable for the wife of the stake president to be involved in activity with this kind of negative potential.

However hypothetical his concern, this was something approaching a direct order. I was the wife of a stake president, committed to supporting him and his calling, and so my life with Exponent II ended. Nancy Dredge became the new editor and served for many years, as well as signing on for another tour of duty recently. The paper celebrates its thirty-year anniversary in 2004, continuing to provide a friendly place for publication for many women. Hundreds of them have worked on the paper over its long life, illustrating the diversity of roles we long ago called for. Editor Dredge notes that there is no agreement on any particular cause and no group point of view beyond recognizing the value of each woman’s voice. Exponent II has taken on hard topics, publishing anguished, angry, and triumphant words. Laurel once said that it was like a long letter from a dear friend, and many readers see it in that light, reading it cover to cover as soon as it arrives.

As for me, I still had plenty to do. I took up yoga which preserved my sanity and brought me peace of mind. In the summer of 1977, we left Boston/Cambridge. My husband, having taken a job at the University of Delaware, was released as stake president, and we moved south, starting yet another life. I have occasionally since been involved in Exponent II activities, watching the continued dedication and excitement of the creators with admiration and pride. I am very glad that the paper is still alive, that women still write about their experiences for the benefit of their sisters, and that they gather at the Retreat.

So this is my Exponent II story. I hope that others will get down their remembrances. This was a magic time when women cooperated and accomplished things. And all this happened in less than twelve years. Do others remember that long ago time differently? I hope they will write their own stories.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue