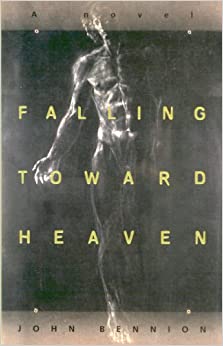

Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 4

from Falling Toward Heaven

The next morning Allison dropped Howard at the Mormon church in Rockwood, which, except for the thin spire, was shaped like a large, sub urban house. Though he had asked, she refused to go inside with him. For all she knew, he might stand and confess his sin; the women in town might sew a red ‘A” onto the front of his white shirt.

Main Street was wide for such a small town. She could see only three businesses—a feed store, a gas station, and a grocery. Houses along the side streets were mostly wooden, painted white or green. The newer houses were red brick; the very oldest were Victorian in style, with walls made from manila colored brick. Some lawns were bright green, others had been burned yellow-brown. Two dry years in a row and the town would blow away.

When she came to the main highway, she turned westward. Up out of the valley, the ground was even drier—tumbleweeds, gray brush, sparse yellow grass, wire fences with gray posts, dusty air. A giant black raven sat on the crossbar of a power pole, waiting for a car to hit a jackrabbit. Allison drove a few miles and suddenly received a gift from heaven—a bar, Willy’s Wet One. Neon beer signs, unlit, were in each window.

Inside were five dusty men, wearing work boots or tennis shoes. The room had half a dozen round tables, grease stains on the top, and a bar along one wall, with red, padded stools. The men turned their faces toward her, frowning, and every beer disappeared.

“Hello,” she said. She felt like a character in a movie—Sigourney Weaver as Clint Eastwood. “Can I have a whiskey?” What else could she say? Four of the men were middle-aged; one looked to be Howard’s age. She didn’t know how to read them: Were they desert bums, drinking away their Sunday, or profitable ranchers stopping off for a nip before a hard day at it?

They continued to stare. “No whiskey here,” the man behind the bar said. “We only sell beer. And we don’t sell that on Sunday.” Every man had his hands under his table. “You have to wait until tomorrow and drive to the state liquor store in Hamblin to get whiskey.”

“I should have just stopped at the grocery store,” she said.

“No whiskey there. No beer anywhere in the state on Sunday.” He looked out the window at her car. “This is Utah.”

“No atmosphere in the grocery,” said one of the men; he wore suspenders, a white shirt, and had a pot belly.

“Vern,” said the young man. “We’d need some music before you could call this atmosphere.” He stood and walked toward a jukebox, a quarter extended in his fingers.

“No!” said all the other men. “None of that stuff.” The young man shrugged his shoulders and returned to his seat.

“You lost?” another man said—levis, cowboy boots, and a toothpick. He grinned at her, an old flirty guy. “Or just passing through?”

“Passing through to where?” she said. Their laughter came sudden and loud as if the joke had been told before. “I’m visiting Howard Rock wood. He went to church, but my nose led me here.” She sniffed and looked under Cowboy’s table. “Well what do you know, a beer in Utah on Sunday.”

He lifted his bottle, taking a swig and grinning. “Walter’s Howard?”

“Are there two Howards in this town?” she asked.

“I thought he was on a mission.”

“He just finished,” she said. “I gave him a ride back.”

“I thought he had to come home and get released before he went anywhere with a woman,” said the man wearing the white shirt.

“You’re one to talk, Vern, about obeying the finer points of the law,” said a man in overalls. “That isn’t a bottle of milk you have clutched between your knees.” Everybody laughed again.

The door opened and Walter walked in. He started when he saw Allison but recovered and sat on the stool next to her. The bartender put a coffee in front of him. “Thanks, Willy,” said Walter. He turned to Allison. “Mormons don’t drink coffee. So Emily won’t let me have it in the house. I have to come out here to get a cup.”

“Howard better not try something like that on me,” she said.

Willy took a beer from under the counter and put it in front of her. “We just left Utah,” he said. The other men put their beers back on the tables.

“Unless the mission president released him before he left,” said Vern.

“That’s Vernon Todd,” said Willy. “He’s got only one train of thought, and that one’s generally late.” Everyone laughed except Walter and Vern.

“So how’s life at home?” said Cowboy. He grinned at Walter.

“Don’t ask. It’s like my wife has become a different woman.”

“She woke up to herself,” said Allison.

“That’s right,” said Walter. “I’m just having trouble getting used to it.”

“Howard was in Texas, wasn’t he?” said Vern. “He was writing steady to my niece, Belinda. According to her, they was about ready to send out wedding announcements.”

This town is so small it’s nearly incestuous, Allison thought. “Texas is where I met him.”

“You’re a Texan,” said Vern. “You met Howard down there?”

“You’re a curious man,” she said.

“Howard’s a good kid,” said Willy; he was watching Walter, who slowly drank his coffee. “You’re lucky to have met him.”

“Yes, I am.” She took a drink. “I’m on my way to Alaska.”

Willy looked from her to Walter.

“She’s got Howard thinking he wants to go with her,” said Walter.

“And the sons of Israel wanted to take away Benjamin,” said Willy, “the light of Israel’s eye.”

“I’m not forcing him,” said Allison softly.

“Not hardly,” said Walter. “It isn’t your will or words that’s constraining him.”

“Willy’s a frustrated preacher,” said Overalls. “He came here twenty years ago to save all us Mormon heathens. Couldn’t find any takers, so he opened up a bar. Been thriving ever since.”

“This is thriving?” said Willy.

“Wet Willy’s Desert Chapel,” said Cowboy. “Last chance at salvation.”

“I was in Alaska one summer,” said the young man. “Beautiful country.”

“You’re going to have to offer Howard a higher salary,” said Willy to Walter. “Give him an incentive to stay and help you run your place.”

“Can’t even pay myself what I’m worth,” said Walter.

“And that’s only two bits a year.” There was more laughter.

“Offer them the honeymoon cottage,” said Cowboy. “Let them move into Max’s old cabin. How can she refuse an offer like that?”

“I have a job in Anchorage,” said Allison. “Writing software.”

“Writing software,” said Willy. “I need to buy a computer to track my finances.”

“Willy, you don’t need a damn computer,” said Overalls. “You could figure your finances on the toes of a one-legged man.”

“Can I get a computer that flashes a red light above the door when a deadbeat comes in?”

“That red light would be flashing all the time,” said Cowboy. “People would think you’ve turned this place into a bawdy house.”

“So two bits and the honeymoon cottage won’t cut it?” Willy asked her.

“Does this cottage open onto the beach?” she asked. “Does it have cable TV?”

“Mice and an outhouse,” said Cowboy. “A bucket for drinking water. But it has a beach. Down the valley is a murky hot springs with dead Goshutes floating in it.”

“Just Howard’s style,” she said.

The young man lifted his can. “To your success.”

“Whose success?” said Walter.

“Her success, and Howard’s. He was in my graduating class. May you have a damn good time together in Anchorage.”

“When’s the wedding?” asked Vernon.

Walter looked at his coffee cup.

“No wedding,” said Allison.

“But—”

“Vernon Todd,” said Willy, “put a fist in it.”

“Your train was just derailed,” said Overalls.

“To pleasure, prosperity, and long life,” said Cowboy, lifting a can.

“Some of my sons are scoundrels,” said Walter, staring at his coffee cup. “But Howard has a pure heart.”

Allison raised her beer. “To Howard, the pure of heart. May it always lead him to someone who will care for him.”

Walter lifted his cup high. “To Howard.” Then he turned his stool to ward the men sitting at the table. Allison drank another beer, listening to their talk about the drought, the Hunsaker woman whose husband had left her a month before she bore him twin boys, the threat that the Forest Service might raise range fees, and the fact that Gerald L. Hansen should never have been called as bishop because his kids were too wild, not proper examples.

Howard walked alone into the crowded chapel and saw Belinda across the room. He was surprised by the rush of affection for her. In some other universe, he was sitting next to her, planning their wedding in a couple of weeks. A hundred years earlier, he could have married both women. But he couldn’t imagine Allison and Belinda lasting five minutes in one house: What is the definition of critical mass?

His last time inside the church, he had given his farewell talk. His eyes brimming with tears, he had gripped the pulpit and looked down into the faces of the ward members, people who had been as constant as trees to him: old farmers in suits, their wives in dresses, his friends, including Belinda, who had come to wish him well.

“All things are possible to them who believe,” that younger self had said. “If I have enough faith, I can baptize hundreds, like Paul or Wilford Woodruff.” He had left town swathed in glory, a soldier in God’s army. Then as now, he smelled the varnish on the oak floor and benches, trailed his fingers across the white plaster walls.

Brother Harker waved. “Howard,” he called. “I mean, Elder Rock wood. It’s still Elder Rockwood.” People surrounded Howard: Sister Stukey, Brother Anderson, the Petersons. “Good to have you back. You look great. Nothing like seeing a strong returning missionary to give my own testimony a boost. I missed you.” He felt odd that his life had transformed and they couldn’t see it in his face. How would their smiles fade when the word had time to spread?

Belinda sat across the room between her parents. She turned when he entered but jerked her head forward again. The day before when she had first seen him and Allison together, she had swung her car around, nearly running him down.

Brother and Sister Jenkins, his parents’ neighbors to the north, entered from the foyer. They scanned the congregation and hurried to greet him. Brother Jenkins gripped his shoulder. “It’s good to have you home. Talk to you later.” Howard walked to the stand and sat next to Brian Samuelson, who had returned from his mission as Howard was leaving. Sister Jenkins, who had taught him Sunday School when he was in high school, took his hand in both of hers. “I can hardly wait to hear all about it,” she said. He still felt her touch on his hand as she sat next to him on the bench. Allison thought he had come to church out of a desire for self flagellation. She was partly right, but he realized that one motive was rebellion—the desire to shock the pious. He supposed he should pray for a spirit of contrition, but that would require him to leave Allison, because she wouldn’t marry him. The thought of leaving her was terrifying.

Howard’s mother moved through those who stood waiting for the meeting to begin; she saw him, nodded, and turned away again. Women walked across the chapel to talk with her. She laid her hands on their arms, smiling. She glanced at him again, frowning. Then her face became animated, laughing at something one of the women said.

Bishop Hansen rushed in and stood behind the pulpit. “I’m pleased to welcome you to sacrament meeting.” He pointed toward the back. ‘As you can see Howard Rockwood has returned from his mission.” The people in the congregation turned again and looked at Howard and Sis ter Jenkins sitting together. The bishop smiled at him then read the announcements.

Under his breath Howard said, “He’s going to ask me to come up and talk. I can’t do it.”

“You’ll do fine,” Sister Jenkins whispered. “All that practice in the mission field.”

The bishop turned the time over to the chorister, who led the congregation in singing “Zion Stands with Hills Surrounded.” Barney Thompson stood to say the invocation. While Barney prayed, Howard watched Belinda from partly closed eyes. She didn’t bow her head; she bit her lip, seeming—what?—frightened, angry, hurt? As he had driven to Allison’s apartment, he hadn’t thought once about Belinda. He wished he had been smart enough to avoid hurting her or anyone else but immediately realized the impossibility of such a pure and insular sin.

After the prayer came the sacrament song, “Behold the Great Redeemer Die.” The deacons, one of them Belinda’s little brother, moved down the rows with trays of broken bread, emblem of Christ’s broken body. The room was quiet except for a few fussing babies. He told himself that a person ate damnation when he took the sacrament unworthily, but the thought came from outside, as if from God or the town. He felt inflexible, even ironic about his own grasping for guilt, as if shame could make up for what he had done.

A deacon stood in front of him, the tray of bread extended. He passed it on to Sister Jenkins, who stared at him before taking a small piece. He knew Christ could take his sin away if he repented and gave up Allison. He knew he wasn’t ready for repentance. The second priest flipped his hair back out of his eyes and said the blessing on the sacramental water. After the prayer, before the tray of cups could come to Howard, he left his seat, aware that everyone was watching, and went into the hallway. He paced back and forth. One kind of damnation, he thought, was being unable to feel the horror of his own sin.

He leaned against the door jamb, just out of sight, until the sacrament was over and the bishop stood again behind the podium. Having been a missionary and having received the Melchizedek Priesthood, he would be excommunicated for his fornication with a woman who might leave him at any time. Around the edge of the door, he saw his mother frown and look back at the bench where Sister Jenkins sat alone. He could walk out through the foyer and across the lawn, never have to face anyone in Rockwood again.

Why had he coupled himself to Allison? The answer, unlike his futile efforts to feel shame, was clear. She rose two-handed before the net and caught the soccer ball. She undressed him in the motel room, quiet hands moving across his skin. She sat on the couch in her apartment, face in tent, body inclined forward. She boiled the air with her profanity. She was as sudden as lightning, as crisp as a crack of thunder. Still, when he walked back to his seat and the members of the ward turned their faces toward him, white coals burned in his chest.

Bishop Hansen was still talking. An excommunication court is a court of love, they used to say. Now they called it disciplinary action, but the function of both was to flush sin into the open. Perhaps that repudiation would allow him to reconnect to his former self, a self he wasn’t sure he wanted. If he refused to go with Allison to Alaska, if he stayed to help his father, she would leave. He would confess his sin to the stake high council.

In 1930 Solomon Rockwood, James Darren’s son, had been excommunicated from the church for taking a fourth wife, a woman twenty years his junior. By then members of the church had adopted the nation’s revulsion against polygamy; he could keep his three legitimate wives, but taking a new one had been an act of apostasy. Kids who went to the cemetery for a thrill said they could still hear him moaning. He was warning others against his mistake, they said. Once Howard had read part of Solomon’s diary. “August 15, 1934. It has been over three years since anyone in Rockwood has spoken to me in friendship.” Death was not the ultimate isolation.

At the pulpit, the bishop finally finished his testimony. “We’re going to hear from Elder Rockwood later, I know.” Howard’s mother shook her head slightly. “But I thought you’d like to hear briefly from him now.”

I spent two years serving God, thought Howard. He stood and without moving to the front, prepared to speak from his seat, as people often did when bearing their testimonies. One of the counselors, a man Howard didn’t know, was whispering something in the bishop’s ear. The bishop shook his head vigorously.

“In Navasota, Texas,” Howard said, gripping the bench, “lives a widow and her children, three of them, the Valdez family. We had passed her apartment many times on our bicycles; the kids were always dirty and running wild. We knew later from talking to her neighbors that she saw men in the evening for money.” He looked across the ward. Sister Sorenson, Brothers Jenkins, Hurst, and Wilkins, Belinda, her parents, Sister Jenkins—all the people he had wanted to see again. Not even the babies were making noise. “One day we passed her house and had the feeling we should knock. No one seemed to be home. Then a small child answered.” He took a deep breath and went on. “She was sitting inside on the couch with her boy, bathing his forehead with a damp rag because he had a high fever. We told her who we were, and she didn’t want to talk to us. ‘Go away,’ she said. ‘Can’t you see I have a trouble today?’ I told her about the power the priesthood has for healing the sick. Then she let us lay our hands on her child’s head. When we passed again the next day, she was waiting in the street. ‘My son is well,’ she said.” Howard looked over the people, remembering the weeks they had taught Sister Valdez. Her eyes had grown brighter and clearer as she learned the truths of the gospel. “She began surprising us. When we came to teach, she would give us the gifts of her sacrifices. ‘I told the men to stay away. They are no longer welcome here,’ she said one night. ‘Today I took my wine and poured it out in the garden. I smashed the bottle.’ One day she said nothing, but her place had been scrubbed, the children bathed.” One by one she had packaged the sins of her life and laid them aside, an arduous labor. Watching from the outside, he knew her steps were firm, steady, as she moved toward her own salvation. She had been a simple and sure woman, believing everything they said. Still gripping the back of the bench, Howard let her clear spirit fill him and he spoke to the people of Rockwood from that feeling. “Jesus took her sins away. He can take away my sins and all of yours. Jesus takes away our sins.” As soon as he sat down, the clarity left.

Sister Jenkins reached to touch his arm. “Very nice,” she said. “Exactly right.”

He breathed the smell of wood varnish. Out the open back window the cottonwood leaves rustled. All his life he had been taught that the universe was simple and unitary; now he knew it was not. Opposites were true, paradoxes were as commonplace as stars. As an act of faith, he chose the church and Allison both, both light and desire, and finally, impossible sweetness, he felt true before God.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue