Articles/Essays – Volume 31, No. 4

If I Hate My Mother, Can I Love the Heavenly Mother?

Mothers & daughters . . .

something sharp

catches in my throat

as I watch my mother

nervous before flight,

do needlepoint—

blue irises & yellow daffodils

against a stippled woolen sky.She pushes the needle

in & out

as she once pushed me:

sharp needle to the canvas of her life—

embroidering her faults

in prose & poetry,

writing the fiction

of my bitterness,

the poems of my need.“You hate me,” she accuses,

needle poised,

“why not admit it?”

I shake my head.The air is thick

with love gone bad,

the odor of old blood.If I were small enough

Erica Jong, from “Dear Marys, Dear Mother, Dear Daughter”

I would suck your breast . . .

but I say nothing,

big mouth,

filled with poems.

. . . . . . .

Mother, what I feel for you

is more

&less

than love.

When I have mentioned the title of my essay—”If I Hate My Mother, Can I Love the Heavenly Mother?”—to different women, they have usually answered with a startled, “Do you really hate your mother?” Their response has surprised me a little because I thought of my title as rhetorical not confessional. However, I think their question is still appropriate because feminism always sees theological questions arising out of personal experience. In this essay I mix personal narrative with theological analysis not only because I see this as effective methodology but also because my thesis assumes that all of our theological constructs are based on personal and cultural preference.

Although my essay explores my relationship with my own mother, I felt defensive when women asked me if I hated my mother because their question seemed to imply that, if I do, I may not be the good person they thought me to be. So perhaps I should begin by assuring you that I do not hate my mother. With Erica Jong, I think I can say that what I feel for her is “more and less than love.” I am not close to her, but I feel deeply rooted to her. I seldom talk to her, but I think about her often. I sometimes feel angry at her passivity and denial, but I am also deeply sympathetic to her pain and struggles. There are many things I admire about her, but I am also afraid of becoming like her. At times when I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, when I have not thought to pose, I can see her in my face. And I shudder. While ambivalence is closer to what I feel about my mother than hate, in this essay I want to focus more on my negative images of the mother figure. In describing a painful encounter, I hope to show a process for healing. The importance of understanding my dark feelings became clear to me because of a dream I had several years ago.

In the dream I am sitting in an outdoor cafe with a group of women from the Mormon Women’s Forum. We are worried about what the church is going to do to us. Some of the women keep saying that there is a man who is coming to destroy us and that we must be careful. I am sitting quietly, not knowing whether to believe this or not. As we sit there, we see a huge, imposing, and frightening figure approaching us. “Here he comes,” scream the women. But as the figure comes nearer, I can see that it is not a man but a very large woman, at least three times the size of a normal person. She is dressed in black, like a witch out of a fairy tale, even down to the broom she is carrying. As she rushes toward us, the other women all begin to point at me and shout, “She’s the one to blame. It’s not us you want. Get her.” The witch whirls around toward me and begins to beat me ferociously with her broom. It is excruciatingly painful. I try to protect myself against her blows with my hands, but it does no good. As I cower beneath her, I look up at her hooded face. To my great surprise, I see my mother’s face.

When I awoke from this dream, I was sweating and shaking, too frightened to go back to sleep. It was like a childhood nightmare. In the days following the dream, I thought about it often. Since then it has become one of those archetypal dreams that can be mined for years for the richness of its symbols. I will not mention all of the possibilities here. (Some of them are a little embarrassing to confess—for example, my fear of rejection from other women.) What seemed the most significant about the dream, though, was the witch figure who was my mother. It absolutely astonished me. What could it mean? My own mother was never cruel. She was the absent mother, not the devouring one. Why did she appear like this in my dream? Why was she so violent?

As I meditated on the dream, I realized I had never dealt with my anger at my mother for the ways I had felt abandoned by her. I had always tried to understand her and excuse her. I had even taken over the mothering role. I could be strong, even if she was not. Because I did not feel mothered, protected, or nurtured by her, I gave up all desire for a mother. I wanted to nurture others, but I was uncomfortable with anyone nurturing me. I realized that even in my search for a female God, I was put off by the mother image. I wanted a Goddess—a strong female God—but not a Mother God. The dream made me realize that one reason I could not accept a mother figure, human or divine, was because I had not allowed myself to fully feel or admit all of my negative feelings about my own mother or the Heavenly Mother, who also appeared to have abandoned me and left me alone and unprotected. Like my real mother, she seemed to have withdrawn into the bedroom to sleep. She seemed invisible and powerless like her daughters.

A series of questions began to occur to me: If I hate my mother, can I love the Heavenly Mother? If I hate my mother, can I love myself? If I hate God, can I love myself? If I hate myself, can I love my mother or the Heavenly Mother? I wanted to put these questions in the sharpest terms possible—love/hate. There was no room for ambivalence at this point. I had to let myself feel my strongest and darkest feelings, about my mother, about myself, and about God.

I began to see the various ways all of these relationships are intertwined. Of course, making these connections is not a new idea. Ever since the advent of depth psychology, it has been commonplace to see our relationships with our parents as crucial for working out our self-identity. We may completely disagree with Freud’s theories about child-parent relationships, Oedipal and otherwise, but I think most of us would agree with his basic assumption that the parent-child relationship is fundamental both to personal development and self-understanding. We may dislike Jung’s ideas about archetypes (certainly they are not very popular in current scholarship); but we may still find ourselves being controlled on some level by our unconscious mother and father images. Freud (and Jung too) also stressed the way our god figures are projections both of parental/father (and mother[1]) figures and of our own desires for the transcendent. Jewish scholar Howard Eilberg-Schwartz has noted: “[I]f we agree with nothing else from Freud, he was certainly right about the ways in which divine and parental images are entangled. And the possibility of connecting to divine images, whether male or female, clearly is related to the relationships we have to our mothers and fathers.”[2]

Since depth psychology has also been used to undercut belief in God by treating religion as merely a projection of and wish for an ideal, I find it intriguing that some contemporary theorists are taking god-images more seriously. They are not simply seeing belief as the product of naive minds but as a way people have of working through their notions of the ideal and the good in the process of constructing a self and a society.[3] The truth may be that we cannot escape the notion of God. The philosopher Nietzsche, famous for his God-Is-Dead slogan, hinted at this when he expressed his fear that “we are not getting rid of God because we still believe in grammar.”[4] Grammar, like God, sets up an ideal and expectations for norms and conformity of behavior. But can we ever escape grammar as long as we use language? Even if we acknowledge that grammar should be more of a description than a prescription, language functions on the basis of the patterns generally used by the majority of the speakers of any given language. Without patterns, generalizations, and abstractions, communication would be impossible. French theorist and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan argues that individual identity and subjectivity begins with a person’s entrance into language. The entrance of a person into culture and language happens with a loss because no one feels that any representation, image, or description in language can fully express who she is. Therefore, we rely on transcendental signifiers or universalizing symbols to cover this sense of lack by opening up fields of speech or subjectivity. (I am attempting here to give the core of a very complex theory.[5]) The thesis of this essay is that we need such transcendental signifiers in order to construct a self, and therefore self-understanding cannot come without an examination of our god-images, which we all have whether we consider ourselves believers or not. For the non-believer, such an examination forces the acknowledgment that disbelief, as well as belief, is formed as much by personal preference and metaphor as by evidence. For the believer, it forces the acknowledgment that even if God is real, this does not eliminate the possibility that projection and cultural metaphors are involved in creating our perceptions about God. And whether we believe or not, our feelings about God tell us something about our relationships with our parents and about ourselves—what we desire and what we fear. Whether God exists or not, “God” is intertwined with our concept of self.[6]

I happen to be a believer. I have tried very hard not to be, but I can not help it. At several crucial points in my life, I have felt overwhelmed by the love of God. I am also drawn emotionally to the idea of Christian salvation. A God who puts aside his glory to take upon himself the sins of the world is a very powerful idea to me. It has been the only way out of some existential black holes I have found myself in. I have faith that God is real on some level. But even if I am right about this (and of course I have doubts), I still know that my pictures of God are incomplete and colored by my own desires, fears, and cultural baggage. Knowing God, like knowing ourselves, is a lifetime process, and more. Joseph Smith’s statement has always fascinated me: “If men do not comprehend the character of God, they do not comprehend themselves.”[7] And I think the opposite is true too: Knowing ourselves is the first step toward knowing God.

Do we want a personal God? Or do we want a God without a personality one who is simply a loving, creative force, or power for good? Do we want a male God, a female God, or both? Or maybe we want an androgynous God. Do we want one God, two Gods, three, a pantheon? Do we reject the idea of God altogether because it feels like a foolish, unscientific projection? Or maybe we reject God because the last thing we want is another authority figure. Whatever seems superior to us, whatever belief or non-belief appeals to us, reveals something about what we perceive as the ideal. It shows us what our sense of “good” is. It shows us something about our deepest longings and perhaps our deepest conflicts. For example, one of the problems I have is deciding what kind of God I really want; I like all of the possibilities I have just listed. I want God to be both personal and impersonal as it suits my needs. I am not arguing that God can be anything we want him to be. More orthodox Mormons would argue that God is simply what he is in our canonized writings and that we need to accept that. My point is that those writings are incomplete and overlaid with human interpretations. Therefore, we cannot fully see what God is until we strip away our own prejudices and unveil our own desires. This is the thesis of C. S. Lewis’s wonderful book Till We Have Faces: we cannot see the face of God until we have faces of our own, or in other words develop our own identity and character. Perhaps God withdraws from us in this life to give us the independence that makes that possible.

I love the following passage from Jane Smiley’s satirical novel Moo because it deals subtly and humorously with the way our experiences shape our pictures of God and goodness. I also like the way Smiley plays against the Western preference for a personal God. The character Marly, who belongs to an evangelical Christian group and is a cafeteria worker at the local university, has decided to leave town and her fiancee, even though he is a wealthy and powerful man at the university and in her church community.

She had changed because she was tired of Jesus, the way He came to you and sat with you, the way He had to be a man in order to be human. Every body in her church was always talking about how happy it made them that Jesus was right there, at your elbow, helping you along and keeping you on the right path. What could be better than a personal savior? But Marly resented the way Jesus counted on you needing Him like that. He never stepped back. He always wanted something from you. You always had to do something to please Him.

She came to the top of the hill. The road beside her continued up, over the bridge. The snowy drift at her feet spread away like a giant apron past the highway below and into the dark filigree of the woods beyond. The pat tern of it was rather grand—the rounded shapes of the hills and the horizon carved by the precise parallels of the highway, the quiet blazing azure, white, and black of the natural world animated by the hurtling bright colors of cars and trucks, and Marly herself the only visible human. The grandeur of it was peaceful and soothing. She felt invited into the picture, perhaps noticed, but not focused on. Jesus, she thought, was back in town, nosing into every body’s concerns but God was here, large and beautiful and satisfyingly impersonal.[8]

As I have thought about the ways our experiences are intertwined with our pictures of God, I have realized that dealing with my negative images of the mother figure, human or divine, was important for me if I was going to understand some of the things I don’t like about myself. It was important for me if I was going to figure out some of my own ambivalent feelings about being both a daughter and a mother. And it was crucial if I was going to understand the ways in which I have a hard time relating to God.

I have argued on many occasions that the Mother/Female God is crucial for the healing and empowerment of women. Jewish, Christian, and even secular women have said the same thing many times.[9] We all recall the much-used phrase “when God is man, man is god.” I still believe that a concept of a female God (or goddesses) is essential for the equality of women. However, I have also come to believe that a female God creates problems for women too. Like any good thing, there is always a shadow side. It is a mistake to oversimplify symbols or relationships, or to see them only in one way. The symbolic and relational systems of every culture are always complex and full of contradictions and gaps, leading to unexpected results and ambiguities.[10] And it is in those contradictions where we often find the creative space necessary for rethinking and restructuring old patterns of thought and behavior. The gaps are like a door into a new world.

Last year I discovered a book called God’s Phallus and Other Problems for Men and Monotheism, written by Howard Eilberg-Schwartz. In this book Eilberg-Schwartz says that he has been influenced by feminist theologians and agrees with them that “a male image of God validates male experience at the expense of women.”[11] He says that for a time this made him reject a father god figure altogether until he began to sense his own need for a loving father God. In his search he also realized that a father God creates problems for male identity as well as validates male power. As he puts it: “images of male deities may authorize male domination while rendering masculinity an unstable representation.”[12] He cites the following problems:

1. The male God provides an ideal of manhood, which human males will always fall short of. Eilberg-Schwartz says: “A masculine god, I suggest, is a kind of male beauty image, an image of male perfection against which men measure themselves and in terms of which they fall short.”[13]

2. The Jewish male God also causes problems with masculine sexuality. Men are supposed to want to be like God, but God appears sexless. If he has a phallus, it is hidden. Men are supposed to have sex with their wives and procreate with their phalluses, but how are they supposed to feel about them if God, the perfect male, doesn’t have one? And if God is simply beyond sex or gender, why is he represented in male terms in the Bible and other sacred writings?

3. God is also supposed to be the object of male desire. Jewish men are supposed to love God above all else, even their wives. But men loving a male God so intensely creates unspoken tensions about sexual identity and orientation. Homoeroticism is condemned, and heterosexual marriage is the cultural norm in Judaism. And yet God is pictured in scripture as lover as well as father. This encourages men to want to be the object of God’s desire, since the lover image implies a sexed and desiring God.

4. A male God also becomes a competitor with human males. Just as human fathers and sons find themselves in competition, human males can find themselves in competition for the father God’s power, love, and goodness. And God as heterosexual lover also becomes a competitor for the affection of women.[14]

Although Eilberg-Schwartz feels that feminist theology needs to reflect more on how our relationships with both our parents influence our god images, he does not ramify the ways in which a female God can problematize womanhood in the same way a male God problematizes manhood. But I want to point out the parallels, and in doing so suggest some directions for developing a Mormon theology of God the Mother.[15]

1. A female God provides an ideal which women will always fall short of. This is more complicated for women than men because women do not have as many scriptural examples of what and who the female God is.[16] This is certainly as true in Mormonism as it is in the rest of the Judeo-Christian tradition. In fact, it may be worse in Mormonism because we take literally the gender of God. And, in addition, we believe that women can become goddesses, like their Heavenly Mother. The fact that we know so little about her can therefore causes both an identity crisis and the fear of failing to meet some undefined goal. And of course if any of us express a desire to know more about her, we are punished by the church for our presumption.

2. Is the Heavenly Mother sexless? And is motherhood the only attribute of a female God and therefore our only ideal? Certainly in Catholicism the image of the Virgin Mary as the ideal woman and queen of heaven has made it very difficult for women to feel positive about their sexuality. They are supposed to be mothers without liking sex. In Mormonism we do much the same thing; we insist that God has an eternal body, but we are afraid of talking about it as a sexual body, either male or female. Is eroticism a part of divine perfection? Is procreation the only reason for having a sexed body? Is an eternal body an eternal, fixed destiny? And are women condemned to endless eternal procreation, like queen bees without an escape?

3. Is the female God to be thought of as lover as well as mother, like the Father God? Should she be the object of our desire? And should we want to be the object of her desire?[17] Does this validate female-female relationships? And what does it say about men’s relationship to a female God?[18] And of course there is the problem of how God can be mother, lover, and friend all at the same time. Even if these are taken strictly as metaphors, they can create tensions on a psychological level.

4. Does a Mother God create mother-daughter rivalry and tensions? While it is empowering for women to see themselves reflected in a Mother God, women can also feel some negative emotions. Does this mean we are limited to being what she is and nothing else? What if we don’t like the mothering role? What if we would rather be talking with the men? Are we always to be under her control and shaped by her image?

The problems I have listed are very real on a human, parent-child level; they may seem a little trivial when extended to a divine level. This is perhaps one reason many people opt for the ideal of an impersonal God. Ever since the advent of Greek philosophy, the transcendent, disembodied God has been seen as superior to the anthropomorphic God in Western thought. But why? An impersonal God does not solve all of our troubles with deity. It simply creates a different set of problems, the chief one being this: how do we value our human bodies and personhood if a personless, disembodied God is the ideal?[19] And of course women have rarely benefitted from the idea of the transcendent, disembodied God since they have been seen historically as “guardians of the flesh.”[20] I think that one of the greatest contributions of Mormonism to Western theology is the way it puts the material realm on an equal footing with the spiritual realm. Unfortunately, this concept has been as neglected in practice as has the Mormon concept of a Mother in Heaven.

The fact that a Mother God can create some of the same identity conflicts we have with our human mothers may be one of the reasons some of us have had a problem feeling any connection to her or even wanting her to exist. I think this is one of those unspoken tensions in Mormon feminism and elsewhere too. Because the Mother God often has been held up as a theological solution to all of our problems as women, some women have found it difficult to admit that they never really wanted another mother.[21] One is quite enough, thank you.

To admit you don’t like the Heavenly Mother seems to be tantamount to rejecting female gender or womanhood. And if not that, it seems to be a confession that you don’t like your own mother or being a mother or a woman. And if we don’t like our mothers, how can we expect our daughters to like us, unless we are perfect in every way like Mary Poppins? And saying you don’t like Mary Poppins is like saying you don’t like the Mother God. But not liking our mothers may not be the main reason women reject the Heavenly Mother. What if it is a more complex matter than that? Perhaps the problem centers more on the ways motherhood and the Heavenly Mother are represented. Perhaps it is because our images of the Heavenly Mother are too flat, sentimental, and confined. In our attempt to find a positive female deity, we may have participated with men in creating a Heavenly Mother who is no more than a Hallmark card cliche.

We may not recognize that glowing, overly positive statements about the Mother God can indicate an attempt to escape all of the problems we have with our earthly mothers by creating a static, one-dimensional ideal where we do not have to deal with the complexity or paradoxes of real relationships and real life. The Heavenly Mother can represent a kind of fantasyland where everything is nurturing and whole and good. But why do we want God to be this kind of one-dimensional escape from the world? Will it really bring happiness? As Job asks, “Can we expect good from God and not evil?” Can we always tell the difference?

Just try to create a fictional version of a perfect person, and you will quickly discover how hard it is to imagine goodness without creating a character who is dull, vacuous, and self-righteous.[22] Utopian literature reveals the difficulty of imagining an ideal world that is not either totalitarian or uninteresting. I find some of the matriarchal Utopias described in feminist literature, such as the Chalice and the Blade, to be no better than their male counterparts.[23] Quite frankly, the kind of world they portray appears to me to be boring and oppressive at the same time: boring because everything is flat and non-paradoxical; oppressive because every thing has to be up-beat, nurturing, and co-operative. Feminine power is seen only as positive. Witch figures are seen only as the creation of an evil patriarchy which fears female power. Evil mothers and evil women do not really exist. But we all know they do, don’t we?

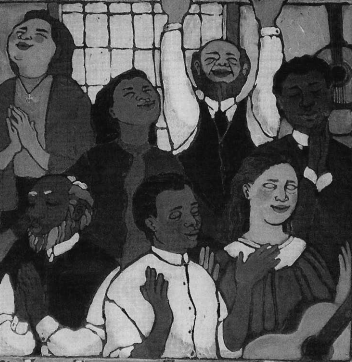

Aren’t nurturing, all-positive mother figures just the same old sentimentalized Victorian ideal of womanhood and motherhood that we have always complained about? Is it really in our interest to see all feminine images as positive? If so, why do we complain about them so much? Why do some of us have such negative reactions to Mother’s Day? I think it is more than the fact that we women are reduced to the mothering role; and it is not simply the fact that motherhood is idealized and raised up as a standard from which we all fall short and about which we all feel guilty. It is also because motherhood is presented in such a narrow way that it appears that there is only one way to be a good mother. Motherhood is represented as the sacrifice of self. Good mothers are always kind, loving, and giving. Being a good mother is seen as the absence of passion or having negative feelings. And to criticize the ideal as a false representation of perfection or even reality is nearly impossible. Adrienne Rich puts it this way:

When we think of motherhood, we are supposed to think of Renoir’s blooming women with rosy children at their knees, Raphael’s ecstatic madonnas, some Jewish mother lighting the candles in a scrubbed kitchen on Shabbos, her braided loaf lying beneath a freshly ironed napkin. We are not supposed to think of a woman lying in a Brooklyn hospital with ice packs on her ach ing breasts because she has been convinced she could not nurse her child; of a woman in Africa equally convinced by the producers of U.S. commercial infant formula that her ample breast-milk is inadequate nourishment; of a girl in her teens, pregnant by her father; of a Vietnamese mother gang-raped while working in the fields with her baby at her side;… We are not supposed to think of a woman trying to conceal her pregnancy so she can go on working as long as possible, because when her condition is discovered she will be fired without disability insurance; … We are not supposed to think of what infanticide feels like, or fantasies of infanticide, or day after wintry day spent alone in the house with ailing children, or of months spent in sweatshop, prison, or someone else’s kitchen, in anxiety for children left at home with an older child, or alone.[24]

I don’t like my mother if I am thinking of some ideal role from which she has fallen short. I do like her when I am thinking about her history and her struggles. I like her when I am not thinking about her as my mother and the pain I feel in my relationship with her. I like her when I realize I don’t have to feel guilty because I have some negative feelings about her.

In most of the pictures of my mother, she has a very serious expression. It is because she is self-conscious about her smile, which is slightly crooked since half of her face is paralyzed and has been since her wedding day. She woke up that morning with a numb face and a red eye because her eyelid had not been doing its involuntary shutting during the night. My mother went ahead with the wedding but missed out on her honeymoon to Mexico. Everyone advised against it; and who were my parents to go against the advice of their families? In her wedding picture my mother is not smiling and she looks a little sad. But even before her paralysis, my mother’s pictures were mostly serious. There is a picture of her as a toddler where she is looking into the camera intently, with some pain. I have always wondered what a child so young is thinking about. What disappointment is she feeling?

If I had to use one word to describe my mother’s life, I would say “thwarted.” Lenna Petersen was the oldest of ten children and grew up in a small farming community in Emery County, Utah, in a town called Ferron. Her mother was sick a lot, so she had to take a lot of responsibility around the house, including the mothering of the younger children. But Lenna had a lot of happiness in her childhood too. She liked her close-knit, large family and community. Her father was the bishop for a number of years, so general authorities frequently stayed in their home. My mother tells how she would sit silently in an inconspicuous spot so that she could listen to the conversations of the men unobserved. She loved to hear them talk about the scriptures and the gospel, and she learned faith at a very early age. She was also a good student and liked school. In high school she even won a scholarship to go to college. However, because she was a girl the principal thought he ought to ask her father before giving it to her. Her father told the principal that they should give the scholarship to someone else because Lenna would not be able to go. And they did.

But my mother went anyway. She attended BYU for a year and a half where she worked one job to pay for her room and board and another to pay for her art and piano lessons. In her second year, Lenna’s parents asked her to quit school so she could help support the family. It was the Great Depression, and everyone was having a hard time paying their bills. Mama reluctantly but dutifully left Provo and moved to Salt Lake City where she got a job as a maid for the wealthy Collins family, who were the Collins in the Tracy-Collins Bank. Lenna was treated like a servant and was made to feel the inferiority of her social standing. Even now she is still very sensitive to anything that feels like condescension. Her family lost the farm anyway and were forced to leave their land. The Petersens (with an e—my grandfather’s family was converted to Mormonism in Denmark) decided to move to Mesa, Arizona. There is an old family photo with the large family and all their possessions piled up on their old black Ford. They look like the Joad family, dispossessed of their land and ready to start a new life.

Mama was twenty-nine when she married Daddy. She had not been able to return to college, but had had a series of jobs, usually working as a cook or a secretary. She had her first baby at age thirty, and then seven more, making a total of eight in eleven years. I think she was truly happy to have all of these children, even if she was not satisfied with being stuck in the house. She was a good mother of young children, and she’s still very good with her young grandchildren because she’s patient and understanding of their needs. But she has always been very depressed. My strongest image of my mother is of her lying in her bed, too tired and sick to do anything. By the time I entered school, I began to sense on some level that I could not ask my mother for help. I had to take care of myself and my younger brothers and sister too. The house was always very messy, so I needed to help with that as well. In fact, the house was the family shame. It became a symbol of my mother’s failure and of the family’s inability to be what we were supposed to be.

I do not want to give you just a negative picture of my family, because that would not be true to life. I think all of my siblings would agree that we had a happy childhood. Our home was chaotic and messy, but there was incredible creativity and freedom as well. It was not a judgmental place, and we were loved, as a group at least. I have to admit that I never felt seen as an individual, but that might have been because I was a third child. Reading was encouraged, and there were always lots of family discussions on various topics. All of us children were smart, did well in school, and have become effective and productive adults. So there was obviously a lot of good things that happened in our home. It was full of freedom and grace.

My father was a quiet, gentle man, who was very responsible and hard-working. He was not particularly successful and usually worked two jobs to support the family. But, like most men of his generation, he never helped my mother with the house. It was her failure (which we girls also shared). The unspoken dynamic in our home was that my mother was the source of a lot of problems, and my father was the reliable one. My mother was embarrassing; my father was someone to be proud of.

I told you that I have always been very sympathetic to my mother’s pain. From a very early age I tried to understand her. I saw the way her mother treated her. My mother’s mother lived only a couple of blocks away from us. Unlike my mother, my grandmother was a meticulous housekeeper and very energetic. She was always busy with some project: doing genealogy, making drapes, recovering furniture, writing poetry and family histories. And she always had something she needed my mother to do: take her here, get this for her, and so forth. Yet she gave little thanks to my mother for her help, and always seemed to have some criticism of her, especially of her house. According to my mother, this had pretty much been the pattern of her life. A lot was demanded of her. And then instead of receiving praise or thanks, she was criticized for not doing the job right. The boys in the family, on the other hand, were encouraged and praised a lot.

No wonder my mother had such an inferiority complex. No wonder she seemed so overwhelmed all the time. No wonder she had a hard time finishing a task. I remember that by the time I was in high school, Mama would periodically sign up for some type of project. Sometimes it was a class at the local community college, sometimes it was a correspondence course of some type or a sales program. Initially she would be excited about the possibility of doing something creative or of accomplishing something she could be proud of. But usually after a couple of weeks of classes, she would quit and withdraw to her bed. She got no support from my father in these endeavors. In fact, he was always relieved when she quit because it meant less stress for him.

As I look at my mother’s life now from a feminist perspective, I see how much she was a victim of a patriarchal culture which makes it difficult for women to feel valued or find a way to feel successful. She desperately needed something outside of the home where she could be acknowledged as worthwhile. She never found it and was never encouraged to find it. She was never encouraged to find her desire. Growing up in a generation where depression was not acknowledged as an authentic illness, she was always seen as weak and lazy. Her real gifts were ignored and overlooked because they were not the ones she was expected to have as a Mormon homemaker. This was especially true at church. She never fit into Relief Society and has had few female friends. Although she is a woman with strong spirituality, this has always been overlooked because it is not the quality valued in women. Women in the church are only valued if they can do Relief Society service. And my mother could not.

Although I have always felt deep compassion for my mother, I have not been close to her. It is partly because of her and partly because of me. Because of her own lack of self-worth, she has a hard time validating any one else. She is always very focused on herself and her own problems. She is not a complainer, but she is self-absorbed. She is always so worried about being perceived positively and being acceptable that she will often strike a pose that is not true to what she feels and is. I have a hard time dealing with this, and I have a difficult time talking to her because it is such a struggle to get her into a real conversation.

I also have a hard time being close to her because I have terrible fears of falling into her patterns. I too have fought depression all my life and have a lot of anxiety over my performance. I have fears about being overwhelmed with daily tasks and not fulfilling my duties. I worry both about being invisible and also about being too self-centered. Unlike my mother, my depression has driven me toward accomplishment. But I have noticed that none of my accomplishments seems to make me feel worthwhile or that I have really done a good enough job. I have a tendency to feel like a failure no matter how much I do. I have struggled a lot with self-hatred, which does not mean that I do not also have self-love and self-esteem. Our relationships with ourselves are no more simple than any other relationship.

The search that this essay represents is a search to reclaim the value of the feminine—my feminine.[25] The process has taught me that I cannot fully love myself until I have dealt with all the anger I have toward my mother, mostly an unacknowledged anger at her for giving me a heritage of defeat. Before my dream I did not think I was angry because I had worked hard to understand and forgive. The dream showed me I had merely repressed the anger and transferred it to myself. To reclaim myself, I must also reclaim my mother and my Heavenly Mother. According to Marion Woodman, a Jungian psychologist, “Release from repression . . . is less a slaying of the evil witch than a transformation of her negative energy through creative assimilation.”[26] As part of this process, it may be necessary to express hatred, which does not exclude love.[27]

My question (if I hate my mother, can I love the Heavenly Mother?) plays on the scriptural question: “If a man say I love God, and hateth his brother, he is a liar: for he that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen?” (1 John 4:20). If I hate myself for being feminine, weak, and defeated, can I love the Female God?

I have often contemplated God’s command that we should love him. How can you command love? Either you feel it or you don’t. You cannot force yourself to feel it, can you? Commanding people who want to obey all of the commandments to love only seems to encourage lies and self deception. People will say they love God because they think they are supposed to. But will they really? How can we possibly love God whom we have not seen? I see irony in God’s command to love him. The command should make us think about its contradictions and difficulties. It should make us ask, “How can I love God whom I haven’t seen?” and “How can I love God without knowing him?” I see God’s command to love him as an invitation to know him and find his love. And this is both the love God has for us as well as the love we want to have for God. God’s command to love is an expression of his, and I think of her, ardent desire for us to enter into a relationship with them. It is their way of extending their love to us without force.

I do not think we can love either of our Heavenly Parents without also dealing with our anger against them. If you have not been angry at God, then you have never taken him or her seriously; you have not really entered into a relationship. Love always involves a broad range of emotions, which is why it seems easier to love in the abstract. It seems more like our ideal of love if it is not tainted with a complexity of emotions and a history of disappointments. But intense relationships have negative as well as positive interactions. We all hurt each other, even when we do not intend to. Even God, our Heavenly Parents, who are perfect, cannot help but cause us pain because they have put us in an imperfect world.[28] I do not think we women can love the Mother God unless we have also been angry with her. Angry at her absence. Angry at all of our handicaps. Angry at all of our losses. Angry at all the injustices. Angry at our feelings of helplessness.

One of my strongest desires is not to leave my daughters helpless. I do not want to give them a heritage of defeat. But avoiding defeat is not the same as avoiding pain. My own suffering has taught me that growth does not come without conflict. I want to quote another section from Erica Jong’s poem about mothers and daughters because it acknowledges the fact that daughters construct their self-image not only by identifying with their mothers but by opposing them too.

My poems will have daughters

everywhere,

but my own daughter

will have to grow

into her energy.I will not call her Mary

or Erica.

She will shape

a wholly separate name.& if her finger falters

From “Dear Marys, Dear Mother, Dear Daughter”

on the needle,

& if she ever needs to say

she hates me,

& if she loathes poetry

& loves to whistle,

& if she never

calls me Mother,

She will always be my daughter—

And in some ways our daughters will always be our mothers and sisters too. Much of our anger against our mothers comes when we feel they will only allow us to relate to them as daughters, that they will only accept us if we mirror them and fulfill their desires and wishes.[29] This is the other side of the negative mother image; this is the devouring mother who gives life to you only so that you will give it back to her. Motherhood is often seen in this way as the impossible demand, as unsatisfied female desire. It is the lack that can never be filled—the gaping hole of womanhood.

But the devouring mother and the absent mother are really two sides of the same coin.[30] The absent mother is the self-sacrificing woman who has no identity and is only there to give her life to the next generation. The devouring mother sacrifices her children to keep herself alive. But in the process she too loses her identity and becomes the witch stereotype, who in turn is sacrificed in the name of the Father to keep patriarchy alive. Both of these mothers have been used to subordinate and control women.

It is these twin mother images that many of us react against with such violence and fear. They are the two extremes in the spectrum of motherhood. All of us have some of them in us, which may be one reason these images are so fearful. I believe we must redeem them by assimilating and transforming them.[31] We cannot like the idea of motherhood, we cannot like our own mothers, and we cannot like being mothers until we reclaim and redefine what being a mother is. French feminist Luce Irigaray defines motherhood as the process of creation.

… we are always mothers once we are women. We bring something other than children into the world, we engender something other than children: love, desire, language, art, the social, the political, the religious, for example. But this creation has been forbidden us for centuries, and we must reappropriate this maternal dimension that belongs to us as women.

If it is not to become traumatizing or pathological, the question of whether or not to have children must be asked against the background of another generating, of a creation of images and symbols. Women and their children would be infinitely better off as a result.

We have to be careful about one other thing: we must not once more kill the mother who was sacrificed to the origins of our culture. We must give her new life, new life to that mother, to our mother within us and between us. We must refuse to let her desire be annihilated by the law of the father. We must give her the right to pleasure, to jouissance, to passion, restore her right to speech, and sometimes to cries and anger.[32]

While not allowing women to be reduced to the mothering role, Irigaray at the same time asserts the absolute importance of mothering for women. She does this by expanding the meaning of being a mother and by emphasizing the importance of symbols and language in the creation of women’s subjectivity and selfhood. Irigaray’s writings support my view that god-images are crucial for believer and non-believer alike. For her, the idea of God is an essential part of the creation of meaning and personhood.[33] As she puts it:

“God is the mirror of man” (Feuerbach, p. 63). Woman has no mirror where with to become woman. Having a God and becoming one’s gender go hand in hand. God is the other that we absolutely cannot be without. In order to become, we need some shadowy perception of achievement; not a fixed objective . . . but rather a cohesion and a horizon that assures us the passage between past and future. . . .[34]

Women need a female God to insure a coalescence of self in the “path of becoming,”[35] according to Irigaray. Although that female deity must be more than mother, she must also be the Mother God who bequeaths to her daughters their own genealogy, history, citizenship, and the ownership of their own property, bodies, and symbols. This is the mythic Mother who was killed to create patriarchal culture.

“We must not once more kill the mother who was sacrificed to the origins of our culture,” says Irigaray. How do we kill her? We kill God the Mother by confining her to sentimental stereotypes. We kill her by seeing her as less than the Father God. We kill her by not allowing her to speak. We kill her by simply projecting onto her our fantasies of fulfillment without loss. We kill her by not allowing her to have pleasure, passion, and anger. The violent witch in my dream represents not just my need to acknowledge my own anger; it also represents my need to allow my mother and the Heavenly Mother their anger.[36] And what is this anger? What does it represent? For me right now, it symbolizes the parts of myself I hate; it symbolizes what I dislike about the Mother figure and why I am afraid of becoming like her.

“It is a fearful thing to come into the hands of a living God,” says Job. It is frightening to let God be more than a flat picture of a lifeless ideal. It is frightening because it may mean I have to expand my view of goodness and experience things I wanted to avoid. It may mean I have to accept a God who is more than I ever imagined. The angry mother-witch god makes me re-examine all my notions about good and evil; she breaks open my categories. Her violent beating warns me not to kill the mother in me. It warns me against making hasty judgments about myself or about the Mother God. It makes me realize that we kill God (and the god in us) not simply by disbelieving. We also kill God by setting up barriers about what God can and can’t be based on our unexamined fears and desires. And yet we cannot be everything we can be until we let God be everything she can be. In myth the Goddess often appears first in a hideous and terrible form. Only when she is accepted in all her ugliness does she then transform into a beautiful, gracious, woman-like deity. Paradoxically, we may not be able to get beyond the dualistic thinking involved in the good mother/bad mother image until we accept the idea that “the Mother Goddess simultaneously includes both good and evil, beauty and ugliness, nurture and destructiveness.”[37] It is my prayer that we can accept ourselves and the Goddess in all our forms. Let us give life to the Mother and live.[38]

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] It is Jung, not Freud, who dealt with divine female images. For Freud’s theories, see, among others, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (New York: Basic Books, 1963), Totem and Taboo (New York: Norton, 1952), and Moses and Monotheism (New York: Vintage Books, 1957). For Jung, see his Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Pantheon Books, 1973).

[2] Howard Eilberg-Schwartz, God’s Phallus and Other Problems for Men and Monotheism (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 239.

[3] Eilberg-Schwartz, listed above; and Sallie McFague, in her Models of God (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987) and Metaphorical Theology ((Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982), are examples of this. As I argue below, Luce Irigaray is also important.

[4] Quoted in A. S. Byatt, Possession (New York: Random House, 1996), xi.

[5] See, for example, Jacques Lacan, Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981) and Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (New York: Norton, 1978).

[6] Perhaps I should say “selves.” It can be argued that monotheism has contributed to the Western notion that the self is unitary. Some scholars are now arguing that this concept has problems. See “Polytheistic Selves,” chapter 5 in Kathryn Allen Rabuzzi’s Motherself: A Mythic Analysis of Motherhood (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 43-47.

[7] Joseph Fielding Smith, ed., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1971), 344.

[8] Jane Smiley, Moo (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 362.

[9] I could list a hundred books. Standing Again at Sinai, by Judith Plaskow (New York: Harper and Row, 1990), and She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse, by Elizabeth A. Johnson (New York: Crossroad, 1992), both give a good overview of the issues and the sources.

[10] For a good discussion on the “polysemic” quality of religious symbols, see Gender and Religion: On the Complexity of Symbols, ed. Caroline Walker Bynum, Stevan Harrell, and Paula Richman (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986).

[11] Eilberg-Schwartz, 238.

[12] Ibid., 16.

[13] Ibid., 17.

[14] This certainly was true in Medieval Christianity where women often preferred to become the brides of Christ rather than the wives of earthly husbands.

[15] It should be obvious by this point that I think such a theology should see the Heavenly Mother in metaphors that do not restrict her to the mothering role.

[16] I do not want to say there are no examples because this would eliminate the few di vine images and figures we have in the scriptures. For a further discussion of this, see Johnson; or Virginia Mollenkott, The Divine Feminine (New York: Crossroad, 1986); or my essay “Put on Your Strength,” in Women and Authority: Re-emerging Mormon Feminism, ed. Maxine Hanks (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1992), 411-37.

[17] Mariolatry in the Middle Ages became an important way men connected to God as lover. Men like Bernard of Clairvaux pictured Mary as the Lady in a courtly love romance.

[18] In this essay I focus on mother-daughter relationships, but the questions I raise should obviously apply to father-daughter relationships as well, and to men’s relationships with their earthly and heavenly fathers and mothers. Most men would admit that their self identity comes at least in part from their relationships with both their parents, so why isn’t this also the case with their heavenly parents? Why is the Heavenly Mother seen as only a women’s issue? Where are all the men when we talk about her? I have sometimes felt that women have at least one advantage over men: we learn to speak two languages—the language of the dominant male culture and the language women speak among themselves. Women are bilingual; most men only speak one language. We women who are religious learn to relate to a male God; we learn to model ourselves after him, identify with him, and love him; we learn to see the complexity of gender and how easily it can be bent and crossed. This may be harder for men.

[19] Eilberg-Schwartz has an excellent discussion on this issue. He challenges the assumptions that monotheism is an advanced theological concept and that anthropomorphism is primitive. This is not to say that he believes in God literally. But, as he says, “There is no idea that is not embodied in metaphors…” (7). To dismiss the idea of God’s body is a mistake in his opinion because “all sorts of questions fail to be imagined because a whole avenue of research has been closed off by thinking that the Jews did not imagine their God in human form” (22).

[20] This is Luce Irigaray’s phrase (The Irigaray Reader, ed. Margaret Whitford [Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1991], 43). She argues eloquently for the importance of sexual difference while refusing to allow women to be reduced to their bodies. See also Rosemary Radford Ruether in Sexism and God Talk (Boston: Beacon Press, 1983). She agrees with Irigaray that the transcendent God hurts women, but disagrees with the importance of sexual difference.

[21] The same holds true for men. And both men and women may have problems with accepting a Father God. And then there is the conflict people may feel about their split loyalty and unequal love toward the two parents. They may dislike one and identify with the other.

[22] Literary critics have long noted that John Milton’s Satan is a much more interesting and sympathetic character than God in Paradise Lost. Why is “goodness” so hard to create?

[23] See chapters 11 and 12 in Elaine Hoffman Baruch’s Women, Love, and Power: Literary and Psychoanalytic Perspectives (New York: New York University Press, 1991) for an interesting discussion of the contrast between men’s and women’s Utopian literature.

[24] Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, 10th Anniversary Edition (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1986), 275-76.

[25] I am trying not to use the term “feminine” in some reified way. The feminine is always defined in a context, here the context of my personal experience. The fact that goddess images can convey generalized information about people’s views of the feminine does not mean that these images are not also part of a context.

[26] Marion Woodman, “Mother as Patriarch: Redeeming the Parents as the Healing of Oneself,” Fathers and Mothers, ed. Patricia Berry, 2d rev. ed. (Dallas: Spring Publications, Inc., 1990), 81.

[27] For information on hatred of mother toward child, see Elasa First’s “Mothering, Hate, and Winnicott,” in Representations of Motherhood, ed. Donna Bassin, Margaret Honey, and Meryle Mahrer Kaplan (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994), 147-61. For daughters hating mothers, see Linda Schierse Leonard, Meeting the Madwoman: An Inner Challenge for Feminine Spirit (New York: Bantam Books, 1993), and Woodman, “Mother as Patriarch.”

[28] I realize that this raises some questions about God and sin which are beyond the scope of this essay. For a further discussion of my views on this, see Strangers in Paradox by Margaret and Paul Toscano (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990), 107-15.

[29] This describes a major conflict between my mother and her mother. To get the last word in an argument they were having when my mother was in her sixties and my grandmother was in her eighties, my grandmother said, “Lenna, you are sealed to me as my daughter. That means that you will always have to obey me throughout the eternities.” Her statement certainly adds a dark side to the concept of eternal families and sealings. I want to note here too that while I have represented my grandmother as somewhat of a Dragon Lady in this essay, she too has a history of being wounded that makes me sympathetic to her. At age ten, she was sent to work as a live-in helper for a rich woman in town because her family was too poor to keep her. But this is another story for another time.

[30] Of course these types can be described in other ways too. For example, Linda Schierse Leonard calls both of these mothers the Mad Mother, which she then further classifies as the Ice Queen, the Dragon Lady, the Sick Mother (who is also the Caged Bird), and the Saint Mother (the Martyr).

[31] I am purposely using an eating metaphor here. It is sacramental. We take the God or Goddess into us, and in the process both of us are transformed and expanded.

[32] In The Irigaray Reader, 43.

[33] For Irigaray, religion is all about creating meaning in the process of the development of self and culture. She relies on Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1957) in formulating her views about the function of religion: “To have a goal is essentially a religious move (according to Feuerbach’s analysis). Only the religious, within and without us, is fundamental enough to allow us to discover, affirm, achieve certain ends (without being locked up in the prison of effect—or effects)” (Sexes and Genealogies, trans. Gillian C. Gill [New York: Columbia University Press, 1993], 67).

[34] Sexes and Genealogies, 67. She also says: “Man is able to exist because God helps him to define his gender (genre), helps him orient his finiteness by reference to infinity.”

[35] Ibid.

[36] In speaking of the negative mother image, Marion Woodman says: “It is thus her mother’s rage she [the daughter] must redeem by recognizing that rage in herself” (in “Mother as Patriarch,” Fathers and Mothers, 80).

[37] Rabuzzi, 184.

[38] For additional reading, see Kathie Carlson, In Her Image: The Unhealed Daughter’s Search for Her Mother (Boston: Shambala Publications, Inc., 1989); Elaine K. McEwan, My Mother, My Daughter: Women Speak about Relating across the Generations (Wheaton, IL: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1992); Janneke van Mens-Verhulst, Karlein Schreurs, and Liesbeth Woert man, eds., Daughtering and Mothering: Female Subjectivity Reanalysed (London: Routledge, 1993); Rozsika Parker, Mother Love/Mother Hate: The Power of Maternal Ambivalence (New York: Basic Books, 1995); and Ann and Barry Ulanov, The Witch and the Clown: Two Archetypes of Hu man Sexuality (Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications, 1987).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue