Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 4

Sister Dallon Gets Tattooed

Johnny take a walk

U2, “Mysterious Ways”

With your sister the moon

Let her pale light in

To fill up your room

You’ve been living underground

Eating from a can

You’ve been running away

from what you don’t understand

Sister Alice Dallon stopped just outside the safety-glass door, took a deep breath, and walked right in (as the sign suggested), dragging her companion, Sister Mary Kowalski, after her. The interior of the Subdermal Thermal, one of about fifty small tattoo parlors that had sprung up in the general vicinity of 17th Street and Atlantic Boulevard, Virginia Beach, was surprisingly clean. All those images of bead curtains and silver-studded leather, of peeling wallpaper and marijuana smoke were wrong, she guessed, and little wonder—the article that morning in the Times-Register had said that tattoos were becoming socially acceptable and that the fastest-growing element of the tattoo crowd was young career women.

Which wasn’t, however, the reason she and Sister Kowalski were there. No, Sister Dallon had seen a vision, had dreamed a dream; in short, she had no idea why a tattoo was necessary, she only knew it was.

The night before, safe in her down quilt and flannel nightgown, dreaming in a small corner of the basement of a split-level ranch just off Virginia Beach Boulevard near Hilltop, a distinctly female form had walked in on her recurring, only slightly sexy fantasy involving herself and Elder George A’Deau watching the sun come up over the Atlantic and a returning carrier battle group bound for Norfolk Naval Base.

The female form, more like a grandmother than a sex goddess, had been walking up the beach, carrying an open umbrella and tossing huge chunks of white bread to either side of her, a cloud of seagulls spinning around her, mostly obscuring her spacious body. As the form walked closer, Sister Dallon got distinctly uncomfortable about where George’s hands were and where they were going, and squirmed free, jumping to her feet right in the path of the female form and an unfortunate gull.

Feeling like Tippi Hedren in The Birds, except she wasn’t in a boat, Sister Dallon rubbed her head where the bird’s beak had grazed her and fell in behind the form marching down the beach, although just a little wary of the wheeling gulls. Whereupon the scene shifted and Sister Dal lon was sitting in front of a large black desk on a hard, straightbacked— she twisted around to check, yep, Chippendale—chair. The female form was sitting, lounging really, in a huge leather chair behind the desk, wearing a gaudy print dress, almost a muumuu, that, when she looked closely, Sister Dallon realized was covered with gray and white representations of the same seagulls on the beach, along with a few realistic-looking streaks of gull guano.

The form watched her disinterestedly for several minutes, in which time Sister Dallon began to wonder what was going on, and to wonder what the climate control system in the room was trying to do, it being freezing one second and steamy the next.

Finally the form leaned forward to speak, and when she spoke, she spoke with the quiet authority that (in the Mormon church at least) only priesthood leaders and Relief Society presidents could pull off on a regular, routine basis.

“Sister Dallon, I’ve been sent here to your dream—which, by the way, we don’t much approve of, on account of that Elder A’Deau being ug lier’n a fencepost—to give you a message. A real important message.”

Sister Dallon, who had by this time gotten herself thoroughly confused by asking herself whether this was an actual vision or if her subconscious was making it up to entertain her, suddenly remembered that there was a test for angels, D&C 129 or 130, couldn’t remember which, but it was there, nonetheless—ask her to shake hands.

“Uh, I see you know my name, what’s yours?” She stuck her hand out across the desk. The form’s eyes twinkled.

“Handshake test, eh? Well, why not? Might as well give you some sign that I’m on the level—though I might remind you that seeking signs is the mark of an adulterous generation. Put ‘er there, sport,” and she grabbed Sister Dallon’s hand with the kind of I-dare-you-to-cry grip that her district leaders and various lecherous men, both young and old, usually met her with when she was out knocking on doors. But that was the sign, and if Sister Dallon was remembering her scriptures correctly, that meant the form was a translated being, not just a spirit—a little higher than an angel, in fact. Pretty impressive, even if she hadn’t gotten her name yet.

“I hate to interrupt, ma’am, but I still don’t know your name.”

“Didn’t I do that part yet? I keep forgetting—that’s supposed to go first. My name is Sariah.”

Sister Dallon’s eyes went wide. “You mean . . .?”

“No, dear, not either of the Big Two, but a distant relative of the second one. Do you think either of them would have this assignment, child? I mean, Sarah the first has near half a billion real children populating the world she and Abraham made together, with well over a billion spirit kids just waiting to go. And Sariah, my namesake, well she’s got, shall we say, more important things to do? I’m it for you, honey. And to tell the truth, the sooner we get done with this, the better you’ll feel. Remember what happened to Joseph Smith the day after Moroni visited him the first time—fainted going over a fence, not a real pretty sight. We don’t mean to keep you that long tonight, though.”

Sariah paused significantly, and when she spoke again, it was apparent that these were not her words, and that the agent that carried them to Sister Dallon’s heart was higher up even than a translated being.

“Alice Dallon, I have been sent to call you to the position of flag bearer in the Sisterhood. This position holds the responsibility of gathering a spiritually powerful force of sisters together. It is not an enviable position, for you will have many serious challenges to your work. This is the first of many messages you will receive. Good luck, Sister.”

Sister Dallon dropped back in her chair, mouth open like a flounder. What was that all about?

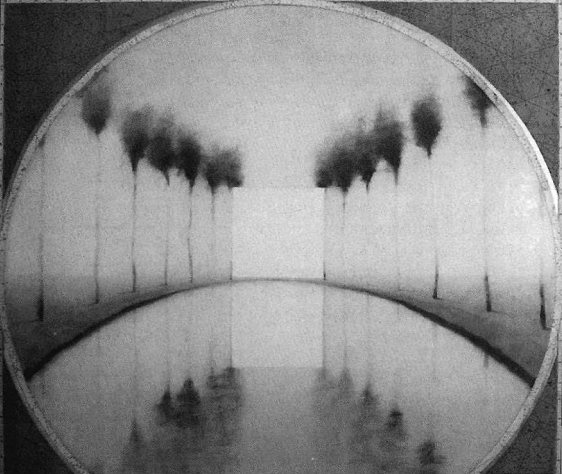

“Oh, and Alice? There’s one more thing. Tomorrow morning, first thing, you’re to go down to the beach, to a tattoo parlor, the Subdermal Thermal, taking your companion of course, and you both will get a tattoo on your right ankle like this,” raising her hand to reveal a white symbol on the black desktop in the form of an interlinked peace sign, feminist symbol, and ankh, thus:

[Editor’s Note: For image, see PDF below]

“This action, Alice, will signify both your acceptance of your call and your first recruiting success. You weren’t given Sister Kowalski for nothing, you know.”

Sister Dallon struggled to the surface of her thoughts and trying to show some semblance of religiosity began to say, “But I am but a lad, and all the people hate me” (Moses 6:31), at which point Sariah broke in with “First off, Sister Alice, you’re not a lad, you’re a full-blown woman, and second, hardly anyone we’ve found hates you—you’re a natural charismatic, that’s why we picked you. Now I’m going to put you back in your dream, okay?”

And the desk dissolved into a lapping ocean and a sliver of sun way back past the clouds and gulls. She looked up to find that she was not being held by Elder A’Deau, but by Jean-Claude Van Damme, hero of several action-adventure movies (all of which she’d seen), the worst of which, Cyborg, had dropped her deep into a crush she’d never really recovered from, and who was wearing only swimming trunks and a great tan.

From there the dream got infinitely more sexy than A’Deau had ever been, and then Sister Dallon woke with a crash to find her companion, Sister Kowalski—most of her 200-pound frame quivering—standing beside her bed with all of Dallon’s sheets and her quilt in one hand.

“What’s up?” Sister Dallon tried to nonchalantly extricate her left arm from under her back, where it was, for some reason, twisted, her left hand in a hard fist under her shoulder blade, which was itself in a fairly twisted state.

“You.” Sister Kowalski continued to quiver, looking at Dallon like she’d lost a limb, which it perhaps looked like from her point of view. “I came in to wake you up—it’s already seven—and I swear it looked like you were levitating. You must’ve been a foot above your bed. What’s going on?”

Sister Dallon, having by now freed her slightly numb arm, began to remember her dream, most of her recollection being however obscured by the almost billboard-sized immediacy of Jean-Claude’s lips, which she reluctantly shook out of her head to get at the kernel of her vision that seemed most important at the time, given Kowalski’s demands and her almost obscene quivering.

“Well, it’s like this . . .” She tried to assume an air of high seriousness, which was immediately hampered by her realization that she had, somehow, gotten her nightgown on backwards.

“I’ve had a vision, Sister Kowalski.”

“You have? Wow! That’s so neat!” Sister Kowalski looked hugely relieved, like she’d been looking for any plausible answer for levitation and visions that fit her expectations perfectly. However, it wasn’t so much that as confirmation that her own odd dream that night hadn’t been blasphemous and that Sister Dallon was, in actual fact, the prophet or, in biblical parlance, prophetess that she, Mary Kowalski, was to follow and assist.

Dallon, feeling acutely aware the whole time of her nightgown and also of a feeling that all this was a little too easy, told Kowalski about her dream, judiciously leaving out the first bit about Elder A’Deau but telling a few of the juicy details involved with Jean-Claude’s participation, which Sister Kowalski didn’t quite understand in the context of a sacred message, but which she stopped thinking about when it became clear that it was a subject too deep and too complicated to pursue.

She could, however, comprehend and even internally debate a little the request or call or command to get tattooed, which she finally determined was a call, convinced, as Sister Dallon was also, by the too-close to-be-a-coincidence coincidental publishing of a five-page pictorial feature in that morning’s Times-Register about tattoos, featuring a sidebar ranking the top ten Tidewater area tattoo parlors or, as they prefer to be called, body decoration boutiques, ranked in terms of cleanliness, artistic aplomb, and relative price, of which the Subdermal Thermal ranked first, with perfect “5”s in every category. It was settled—they had to go.

The next decision was not as easy, because it was, simply, what to wear to a tattooing, and neither Dallon nor Kowalski had any experience fashion-wise with this sort of thing. And to make things more difficult, each of them wanted to wear something different than her counterpart. Sister Dallon, by this time reflecting on the serious nature of her call, wanted to wear regular proselytizing clothes, maybe even her best floor length skirt and linen blouse, complete with the “I’m a Molly Mormon” oversized bow in her hair, while Sister Kowalski, a little embarrassed (to say the least) by the thought of appearing anywhere near a tattoo parlor with a nametag on announcing to the world in general that two representatives of the Mormon church were there and were on a mission to get tattooed, wanted to wear her new Preparation Day attire, which was a powder-blue velveteen sweatsuit with matching sweatband, earrings, and socks, instead.

They settled on a compromising agreement. They would wear their worst proselytizing attire, the old, ragged skirts long slated for Goodwill or, worse, the blouses they’d stained innumerable times at dinner appointments, mission and zone conferences, all-you-can-eat lunch specials at Pizza Hut, the flats they’d scuffed and repolished hundreds of times, scuffed going up irregular, crumbling concrete stairs, running from German shepherds, Dobermans, the odd man with the distinct asthma problem who’d followed Kowalski half a mile when she was in Welch, West Virginia, with Sister Manning, tracting shingle-covered pine shacks filled with dirty-faced naked children, fat women sheathed in thin cotton housedresses, old men half-dead with emphysema and black lung disease; wearing, that is, those clothes most filled with memories both good and worse, mostly worse, to a place both of them were getting increasingly wary of, to the Subdermal Thermal which was, they discovered, not really worth the anxiety they’d invested in it.

The door opened into a small but comfortable waiting area, soft neutral colors on the walls and floor, contrasting pastel colors in the furniture, which was Early Postmodern Functional, squared, cloth-covered foam-rubber and hardwood couches, teak minimalist coffee table covered with the requisite magazines, though the Subdermal Thermal’s taste in magazines was slightly more eclectic than the doctor’s office it resembles. On the long coffee table, arranged in fan-fashion, were: the last three swimsuit issues of Sports Illustrated, a worn copy (Dallon looked to check—latest issue, actually) of Thrasher, the last two weeks of the Chris tian Science Monitor, Time, Mother Jones, The Nation, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, Playboy, Arizona Highways, Easy Rider, Jack and Jill, Reader’s Digest, Backpacker, and, almost buried—Kowalski gasped when she recognized it—the Ensign.

They had sat down in front of the table because the receptionist’s window was empty and a hand-scrawled sign advised them to “Take a Load off—I’ll be Back in Five Minutes! Thanks!” Which they did, waiting almost twice the time suggested, the sign more than a little vague concerning when the five-minute break had begun, waiting exactly long enough, Dallon noticed, for Sister Kowalski to start her toe-tapping, which she usually practiced at breakfast on the linoleum floor of their kitchen, but which the carpet of the Subdermal Thermal muffled so much that she stretched over and tapped on the leg of the coffee table, waiting that is, for anything to stop Kowalski’s nervous habit, which the arrival of the receptionist did.

The receptionist was tall, female, what some might call well-proportioned and others sniff at as too much plastic surgery, black, wearing a starched white nurse’s uniform straight out of Marcus Welby, M.D., except in this case the nurse’s cap was not perched on six inches of round-as-a bowling-ball Afro, but on neck-length dreadlocks. She smiled faintly at the young women in the lobby, as she liked to call it, and asked what they were interested in.

“Tattoos, mainly,” Dallon said, wondering what kind of question was that?

“Have anything special in mind, or didja want to look at the books?” Gesturing towards a bookcase in front of her window/cubicle filled with black notebooks all labeled down the spine “tattoos.” The receptionist beamed her best smile, sensing somehow that these young women would be good customers and might even be interesting to talk to, the usual crowd being about sixteen years old mentally, whatever their physical age might have been. (The article in the Times-Register notwithstanding, most customers were, actually, lowlifes or drunk sailors or bikers looking to increase the amount of printed acreage on their bloated bodies.)

No, these two weren’t that type, though they looked a little like college students, they didn’t look like they belonged there—they weren’t exactly the type she ever thought would be sitting in the lobby of the Subdermal Thermal thumbing through Arizona Highways and Thrasher. Actually they looked like, an awful lot like, the young women who were always over at her neighbor’s townhouse, the receptionist living, as did half of Virginia Beach, in a townhouse hardly larger than the cubicle she worked in, one of millions of identical townhouses stuck together tightly with epoxy and roofing staples in multiples of ten or twelve, complexes stretching across hectares of old orchards, soybean fields, swamps in the dull shine of vinyl siding and quick-drying concrete, complexes too tightly packed, packed so tightly in fact that a good Molotov cocktail or even an incendiary flare might take out an entire zip code before the authorities knew what was happening.

The two women might just be those religious types her neighbor was always talking about, just couldn’t shut that woman up sometimes, especially since she looked down on tattoos and “them kinds of people.” Nurse Caddy, as the receptionist liked to be called—had it stitched in red right above her left pocket, above where she kept extra pens and a lozenge or two—decided to ask, make sure.

“You ladies know Helga Jackson? Lives over in Pointe Woods?”

Kowalski dropped her Arizona Highways and her jaw at the same time. “Uh, no. Why, should we?” Quickly covering her faux pas with a big fat lie.

“No reason. She’s just my neighbor, y’see, and I thought you two looked like some preacher ladies she’s been telling me about. Anyway, what type of tattoo you want? GeorgeTl be back in a few minutes, and he’s got a long afternoon ahead of him, three or four regular customers need touch-ups, expansions, y’know.”

Well, they didn’t know, but it was pretty easy to show her what they wanted. Dallon got up, walked over, took out a pen and drew, clumsily, from memory, the symbol Sariah had shown her in her dream.

“That all? You both want one of these?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Dallon’s eye caught on the red stitching above Nurse Caddy’s left pocket.

“Caddy? That’s a unique name.”

“Yep, it sure is. Guess you wanna know where it came from?”

“Sure.” Why not, anyway? They evidently had nothing better to do than sit around a tattoo parlor listening to the genealogy of this woman’s name.

“Well, you see, it all starts out with my Grandpa Jones. My full name’s Cadillac Euphoria Jones. I don’t know quite why my daddy stuck that Euphoria in there, thought it sounded nice, I guess, kept the rhythm up, anyhow. But Cadillac, now that comes from a joke Grandpa Jones heard some cracker sheriff’s deputy telling a barber one time—Grandpa Jones, y’see, never did have a good education and therefore no good job in his life, just went around odd-jobbing. Anyhow, this one time he was working as a shoeshine boy in this barbershop out in Hopewell, heard this joke. The way Grandpa told it, the sheriff’s deputy had just got a brand-spanking-new Pontiac patrol car, had it sitting out on the curb, and so he tells the barber this joke: Whaddya think Tontiac’ stands for?”

The sisters shrug.

“Stands for: Poor Ole Nigger Thinks It’s A Cadillac. And girl, I mean to tell you, Grandpa, he’d just keel over laughing at that every time he told it. Mainly it was because he never did see what all the fuss was about cars. He didn’t, I don’t think, ever need one except for the one time he moved from Hopewell out here to Virginia Beach. Said it was about time he spent his reclining years right and be near the ocean, ‘stead of up in Flatland there near Richmond. Yep, he walked everywhere he went, and he couldn’t understand why a man would knock himself out day after day just to buy a piece of metal said ‘Cadillac’ on it. Anyhow, that’s where my name comes from, just old Grandpa Jones’s idea of a joke, that’s all.”

“Thank you—that was such a good story!” Dallon beamed into Nurse Caddy’s face, wondering where is that George guy? Isn’t he supposed to be here by now?

Sister Kowalski muttered, “Depressing story if you ask me,” under her breath, turning another glossy page of Arizona Highways, an article on the aesthetic quality of old junked ’57 Chevy trucks, how every xeriscaped yard from Flagstaff to Yuma seemed to be sprouting rusty hulks lately.

Just then, as if on cue, George himself, all 350 pounds of him, most of that bulk (the exterior anyway) covered in exotic body decorations, including a miniature representation of an Uncle Sam recruitment poster on his left cheek, rumbled through the door and belched. He was, besides grossly overweight for his height (5’6″), wearing black plastic-framed glasses, U.S. serviceman’s issue, what the military (those with a sense of humor, anyway) calls “birth control glasses.” His hair was black, shoulder-length, greasy, curly at the bottom, almost permed. He wore the kind of clothes you might expect a tattooist to wear: black heavy metal T-shirt, too small (1978 KISS World Tour); XXL Lee jeans, the fabric a thick dark indigo stressed fantastically at the seams; leather Roman sandals without socks, his fat hairy toes poking out over the front edge; a string of ghost beads at the bottom of which dangled a large uncut crystal.

“These gals would each like a tat like this on their right ankles.” Nurse Caddy looked almost apologetic, like George might just be a volatile man, capable of swift but sure mood swings, which he wasn’t, really, but he always had and would look that way—can’t really ever be too sure about that kind of thing, she thought.

“Uh-huh.” George looked at the drawing, then at the missionaries. “Ain’t you Mormons?”

“Yes.”

“No.”

Dallon looked hard at Kowalski, who’d just lied for the second time. She was sure that being called to do something like this involved telling the truth, so she spoke up again.

“Sister Kowalski here is kinda shy. Yes, we’re Mormons all right. Does that surprise you?”

“Nu-uh. Fact, it kinda scares me. Yuh see, last night I had this real weird dream. Some crazy woman swoops down out of a dark red sky, tells me that at work tomorrow two Mormon women are gonna want tattoos. She tells me that’s why for the past six months I been getting that there Ensign magazine, couldn’t cancel it if I tried, and I did try, believe me. I’ve had more business leave cause of that magazine than even the Atlantic, for hell’s sake. Yeah, I know all about Mormons now, from reading it on my lunch break. What I want to know is what the devil are you getting a tattoo for? From what that magazine says, you folks are stricter’n Baptists. I know no Baptist would be getting a tat.”

“All I can tell you, George, is that the same woman was in our dream last night, and that we were told to come here. We wouldn’t have believed it ourselves if we hadn’t seen that article this morning in the Times Register. ”

“Yeah. That was pretty good, huh? Ol’ George Brimset hisself runs the best tat joint in all Tidewater. Cost me a lot of lunches with that lady reporter for her to say so, though. Hunh. Well, can we get to it? I’ve got a day ahead of me.”

George led them into the tattooing area, which followed the waiting area’s lead of resembling a doctor’s office. Small cubicles lined the walls, each cubicle possessing a doctor’s tissue-covered examining table, a small stool for the tattooist, and a complete set of inks and needles. An antiseptic mist lingered in the air, just enough to remind Dallon of the dentist’s office back home. Her teeth hurt.

Alice Dallon was feeling positively wicked now, like the one time in high school she’d sneaked out of the house and went with her new friend Cathi to a real party, one with boys and alcohol and loud music, one that she’d never forget, her first acquaintance with cheap beer ending with all she’d drank suddenly deciding to go back the way it came, taking her lunch of potato chips and M&Ms with it, splashing all over the black leather couch she’d collapsed on, her party etiquette not yet to the point where, when you recognized “the urge,” you found plant life immediately (shrubs, philodendrons, a self-invited nobody) and hopefully you had a good friend who would hold your hair back out of the way so it wouldn’t end up, as Alice’s did, matted and stinking of beer and vomit and the cheap cologne of the nameless, faceless jock who’d caught her from behind in the hall, mumbling drunkly in her ear, “Hey babe, let’s go back and get in on,” all the while groping at her breasts with his left hand while his right fumbled with the fly of her jeans—no, she’d never forget that, the only motivation she’d ever needed for being a good girl. She wasn’t, however, going to let that stop her now.

George motioned Dallon into a cubicle, then Kowalski into another. He followed Dallon in.

“Take off your shoe and sit right up there.” He puttered around with the equipment, donning rubber gloves, putting on a fresh, clean needle, filling up on ink.

“Okay, now. What you’re gonna feel won’t hurt no worse’n getting a paper cut. Just sit tight, try not to move the leg too much, and we’ll be done in a pinch. ‘Kay?” He winked at her.

Dallon nodded, and George bent over her outstretched leg. She felt a little dizzy. She made herself watch as George put the pen-like apparatus on her skin. He pulled the pen back, the pain shot up her leg, the room lost contact with gravity, whirled, and went dark.

She was lost in the blackness for a few seconds, groping for a light switch, until a faint yellow glow began to seep in, gradually filling in details, corners, edges, grains of sand, hotels lining the beach, the hot sun rising over a cold, still ocean, the tanned well-defined arm around her waist leading up behind her back to the tanned neck and All-American gap-toothed grin of Elder George A’Deau.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue