Articles/Essays – Volume 24, No. 4

They Did Go Forth

Tildy Elizabeth sat by the cradle, Book of Mormon open on her knee. One hand rocked absently while the other traced in painful concentration the small print, dim in the yellow lamplight. Some time ago the bugle had sounded for supper, “Do what is right, let the consequence follow,” and the sisters had gone to the dining room. She wanted to memorize the words so that she could think about them even after they got back. Longing to do this ever since the baby took sick, she hadn’t had a minute alone before.

Of course, taking turns sitting up, the sisters were only doing their duty and being kind, but she knew they’d disapprove—All right, what if Brother Brigham had exhorted against such things as speaking in tongues! Tildy Elizabeth knew there were spirits wandering the earth until the Second Coming. Many’s the time she had overheard the men whispering about the Gadianton Robbers told about in this same Book of Mormon, that brotherhood of murderers sprung up among the Nephites and the Lamanites in the century before Christ came. She’d heard talk about how they haunted a certain rocky gorge near the Nevada line; how the Dixie freighters, hauling early vegetables to the Nevada mining camps, had been scared out of their wits by huge boulders that missed them by inches, and by the very canyon walls closing up to squeeze them to death. Still, the Dixie freighters were going directly against counsel in trading of their substance with the gentiles, and she knew there were good spirits as well as bad! The sisters might think that in conjuring up the Three Nephites she was going against counsel, too—was even daring God. But it couldn’t be helped.

Mostly Tildy didn’t pay much mind to what anybody said, so long’s she felt all right inside. It was only that she had never felt so alone before. She couldn’t stand having folks against her now. It was only that she’d never felt so desperate before.

Over and over she had pondered the question: Where had they backslid? How had they displeased Him? She and Thomas had joined the gospel with their families, shipped via the Perpetual Emigration Fund from Liverpool in ’50, endured constant hunger, cold, and sickness all during the long and bitter voyage, and finally walked behind handcarts from May to September for fourteen hundred miles. They had watched parents and brothers and sisters die. Then, in 1864, just after their first child was born and Thomas was doing well on his Cottonwood farm, they answered Brother Brigham’s call a second time to go five hundred miles into the desert with the “Lead Mission.” Here, on the Muddy, near Las Vegas, they were asked right off by the settlers already there, “Which would you rather have, boards underfoot or overhead? Can’t have both!” But nothing would have mattered, neither the harassing Indians nor the external wind-fretted sand which mowed down sprouting corn like scythes; nothing would have mattered if they hadn’t lost their baby.

They stuck it out nearly ten years. Even then, when Brother Brigham finally saw that the lead they worked was just too brittle and flaky for bullets and ordered the Muddy Mission another three hundred miles up the river, through even more hair-prickling country, to colonize Long Valley—even then Thomas hadn’t grumbled. Even when their second child, Tommy, had gone. Seems like these wildernesses killed children off easier than you could kill flies.

Thomas did not complain. Although it wasn’t specific counsel to join, he turned everything he owned into the Order and worked long and hard to get the coal and fuller’s earth from the hillsides. Timber grew tall and close-fisted on the uplands, grasses were nutritious and deep on slope and ravine. The Order vegetable garden, orchard, and the farms produced unbelievably; she had her own shanty dwelling in the square of shanties; she had managed to carry a child full-term again, had even been delivered by Ann Rice, forewoman of the midwife department. Life in the fort began to be pleasant. Then the Authorities called Thomas on a mission back to England. They said he’d know how to make lots of converts among the miners there. But she wondered inside herself if converts were so important. . . .

Her baby was still nursing when he left; she could still feel the sharp tugging of its gums. It was summer, two years ago, and she had stood in the roadway, dust churning about her ankles, and watched Thomas spring up beside the driver on the high seat of the buckboard, turn and wave to her and the child while the mules clattered off between the soaring green flanks of the valley. Even in memory she felt an ache of pride at her heart. Herself, she had cleaned and carded and spun the wool for his jeans, gathered the kinnikinnic bark, and mixed the logwood for dyeing them black. She had knitted his gray socks, sulphur bleached and braided the straw for his side-brimmed Enoch hat that was like an official insignia of the Order. Only his carpetbag was not new; that, and the sawed-off shotgun he cradled across his knees. In the bed of the accompanying wagon, the Jolley boys lustily fiddled a parting serenade clear to the point of the mountain, but Tildy Elizabeth twisted her waist-apron of store calico she’d worn for the occasion and knew only bitterness.

Now, brooding over the child, obsessed with thought of the Three Nephites, she wondered if that bitterness was the reason for her present trouble: for the first time, trouble she had to bear without Thomas. No use even writing him. In his last letter he had said he was in “flesh and most excellent spirits,” and by the time he could get her bad news everything would be over, one way or the other.

Tildy Elizabeth lifted her head and listened. She heard the sound of wheels crunching the snow, the blowing of a horse. That would be Brother Allen with the milk wagon. From her pantry recess she lifted the quart wooden bucket made by Brother Cox in the Order’s own cooper shop, shrugged into her shawl, and went out into the zero twilight. Ladling full her bucket from one of the great stone crocks, Brother Allen tried to josh with her. His breath puffed out like smoke in the freezing air. But she hadn’t the heart to josh back. Before her the square stretched deep with drifted snow, except for the paths shoveled like wheel spokes from shanties to the dining room crouched impressively behind its flagpole. Now with the sociable goings on, the dining room bulged with gaiety, its windows dripping lamplight on the white ness outside. Tildy Elizabeth could hear an occasional burst of laughter, clear in the brittle air. About now the children would be sitting down at the second table. And then the dishes would be cleared, chairs and tables pushed back against the wall, and the Jolley boys would strike up their fiddles, Old Dan Tucker—Maybe another hour of grace. If the Nephites were going to come at all—!

Brother Allen clucked to his horses, drove on around the square. She stood on the icy planks of the sidewalk a moment longer, staring at the maple and boxelder trees etched blackly against the white fire of the stars, at the frozen tumult of the mountains. Even if a doctor better than Priddy Meeks were closer than Salt Lake, four hundred miles away, he’d be snowed out.

Inside once more, she warmed some of the milk, hoping against hope. But the child still lay in her stupor, motionless as death except for the almost imperceptible lifting of the bedclothes.

Tildy Elizabeth heaved another cotton wood log on the grate, and the coals rustled like the sound of leaves, as if memories of spring were stored up in the dried wood.

Once again she lifted her head to listen. Heart thumping, she flung open the door even before the knock came. But it was only one of the junior waitresses, red cheeks bunched in an excited grin. The little girl curtseyed as she’d been taught by Aunty Harmon, forewoman of all the waitresses, and held out a cloth-covered tray.

“Corn-meal mush and johnny cake and a whole firkin of butter!” babbled the youngster. “And Aunty says she don’t know who deserves a glass of honey more’n you, and there’s a small bottle of brandy in the commissary, if you want it!”

Tildy Elizabeth thanked the child, then shooed her out of the room. Chattering drove her frantic. Even the sight of food drove her frantic. She put the mush and the butter and the honey away, but hesitated with the johnny cake. The baby in the cradle loved fresh-baked johnny cake. Maybe the warm delicious smell might penetrate where sound or sight or touch could not. Quickly she wrapped the loaf in a napkin to keep it fresh, placed it on the bedside chair, and went back to her studying. She had the feeling that if she could just finish this last pas sage—

The knock this time was loud and authoritative. Sighing, she closed the book. That would be Priddy Meeks.

It had begun to snow again. The air outside was curdled with flakes. Dr. Meeks shut the door, stamped snow from his boots, shook it from his shoulders, and went directly to his patient.

It wasn’t that Tildy Elizabeth lacked faith in Dr. Meeks. Watching the light pick out his fringe of chin whiskers, his domed forehead, all the strong, kind lines of his face, she told herself again that he was the best doctor on the Thompsonian or botanical system of medicine in the whole territory. Traveling much, a body would be bound to pick up knowledge. And Priddy himself said his father had been “inclined to new countries.” As a child Priddy could remember moving from South Carolina to Kentucky; as a man he had emigrated from Indiana to Nauvoo, Illinois (where the Lord had appeared to him one day in the fields and counseled him to “quit a-plowing and go to doctring”), from Nauvoo to Great Salt Lake City, thence to the Iron Mission at Parowan, to the Cotton Mission at Harrisburg, and finally to the United Order Mission at Orderville. Undoubtedly he knew a lot. Folks said he had “eyes in his fingers.”

Tildy Elizabeth watched him complete his examination, then look up from the still child’s face to the hovering mother.

“You can’t never tell about the green sickness,” he muttered, shaking his head. “But ‘tany rate, it can’t last much longer.”

He got to his feet, still staring at the baby.

“When you can get it down, give her another good thorough emetic of lobelia. Keep up that poulticing with the charcoal, the hops, and vinegar. Keep the pores of her skin open with the yellow-dock-and dandelion rub, and remember what I told you about cayenne pepper—it’s the best stimulant known in the compass of medicine, ’twill increase the very life of the system—”

He lowered his voice and glanced significantly about the room.

“Have any strange old women been near her?”

Tildy shook her head.

“Well, there might be a witch about! Yesterday I attended a woman with foul spirits. You could see the prints of the witch’s teeth where it had bitten her on her belly and arms. A very good practice for you mothers is to hold out your children to make water in the fire when convenient, and a word to the wise is sufficient!”

He picked up Tildy’s Book of Mormon and slipped it under the child’s pillow.

“You can’t never tell what’ll scare a witch!”

After he was gone, Tildy retrieved the book. It would soon be curfew-time. She hadn’t much longer.

“And . . . He spake unto his disciples, one by one, saying unto them: What is it that ye desire of me, after that I am gone to the Father?” This was in South America when Jesus appeared to the Nephites there, after he had completed his career in Judea and had arisen from the Holy Sepulchre. Nine of the Twelve answered him: “We desire that after we have lived unto the age of man—that we may speedily come unto Thee in Thy kingdom.” But three were silent.

“And He turned Himself unto the three, and he said unto them, Behold, I know your thoughts—for ye have desired that ye might bring the souls of men unto me while the world shall stand,” and because of this, “Ye shall not have pain while ye shall dwell in the flesh, neither sorrow save it be for the sins of the world—”

And the Three Nephites “did go forth upon the face of the land—to behold all the doings of the Father unto the children of men.”

Reading aloud, Tildy Elizabeth did not hear the door open. Only when she sensed the presence of another person in the room, did she look up.

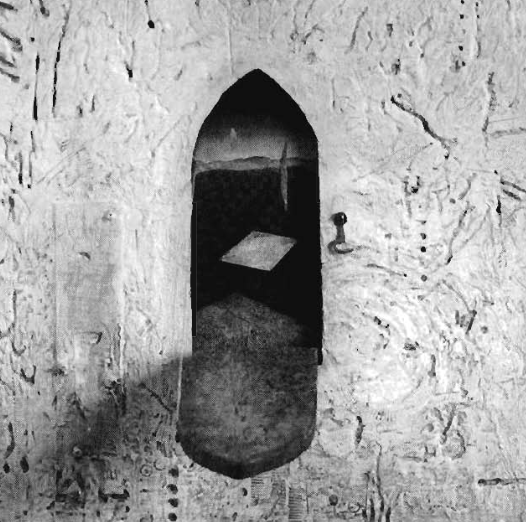

The man was old, with a long beard and snow-white hair. He did not speak but continued to gaze at her. His eyes had an intent brilliance about them, and the skin of his cheeks was as soft and fresh as a babe’s. At a glance Tildy knew that he was from far away. In place of the Order’s coarse, buckskin-laced cowhide boots, the stranger wore store-bought overshoes of heavy cloth; in place of a coyote-skin cap with tail down the back, he wore a store-bought black cap with fine fur about the ears; in place of a buckskin jumper, his black overcoat was long and well-fitting and fur-lined. Considering that he must be a traveler, Tildy couldn’t understand his immaculate appearance. Not even his overshoes were damp from the snow. And there was something vaguely familiar about that high-bridged nose. She had it! Although much older, of course, he looked like the Prophet Joseph.

“Sister Stalworthy?”

Tildy could only nod.

The old man’s voice was mellow and fluted as violin music. Then he smiled, and Tildy felt the ice about her heart melting, running out in inexplicable relief.

“You have a sick child, a very sick child.”

It was not put as a question. The stranger made a statement of fact in that soft sweet voice.

“‘Trust in God and not in an arm of the flesh.’ May I have your consecrated oil?”

Without further ado, he came up to the cradle.

Tildy shut her gaping mouth and scrambled to her feet. Her heart beat like a prisoned thing in her throat.

The old man was kneeling, anointing her baby with the oil, laying on his hands, praying. Never had a prayer seemed so beautiful. Tildy was speechless.

Her visitor lingered a moment longer, then got slowly to his feet. He smiled again.

“Your little girl will get well now.”

Tildy could only cradle the child with her eyes, fondling the inert hands in an ecstasy of hope. Even as she gazed, the baby stirred, looked at her mother, smiled, and said, “I’m hungry.”

Blind with tears, Tildy turned to find the johnny cake, to bless the old man. He was gone! The johnny cake was gone! In an agony of contrition, she realized that he must have been hungry and she too taken up with her own affairs to offer him even food. Thank heaven he’d taken the johnny cake, even if one of her best napkins had gone with it!

She rushed to the door. She must find him, thank him. But the white world outside was empty, silent except for the merriment still oozing from the dining room. Two ways he might have taken: out the sidewalk, on to the valley and outside, or across the square to the party. But although she snatched time from the child to grab the lamp, hurry into the night, and explore both routes, the freshly fallen snow remained unbroken, innocent of tracks. Mystified and chagrined, Tildy went slowly back into the house. And then suddenly she clapped a hand to her mouth. She knew!

***

At the same time, in England, Elder Thomas Stalworthy and his companion trudged along a black, foggy road. Behind them was the village where Thomas had searched out his relatives—cousins and uncles and aunts. He had brought them the gospel, and they had mocked him, stoned him, driven him out.

Both men were cold and very, very hungry. Suddenly Thomas could stand it no longer.

“We’re a-doin the Lord’s work, ain’t we?”

His companion grunted.

“Well, then, He’ll take care of us. ‘H’ask and ye shall receive’!”

Without another word, he flopped down in the mud and prayed aloud.

“H’l don’t mean to rebuke Thee,” said Thomas, “but mebee ye need remindin now and agin like other folks!”

Upon their feet again, the two men felt amazingly refreshed.

“‘E is all-powerful,” reasoned Thomas. ” ‘E wouldn’t ‘ave to necessarily feed us through the mouth!”

Suddenly he stumbled, kicked against something in the mud. He stooped, picked the object up. Incredulously he put it to his nose, sniffed. It was a loaf of fresh-baked johnny-cake, wrapped in a napkin!

***

There was even a drum added to the two fiddles. Tildy was sure not all the ‘igh and mighty boasted such music.

Her youngun dancing beside her, Tildy stood in the roadway, outside the fort, and watched the procession advance up the valley. “Hail the Conq’ring Hero Comes!” shrilled the fiddles, and all about her voices took up the refrain.

Then Thomas was there, in the flesh, waving, coming toward her, lifting them both in his big bear hug. Afterward in the shanty—Oh, long afterward!—when their talk had spurted, and spurted again, and then stopped for sheer inability to swallow the lump in the throat, Tildy collected her senses long enough to unpack his carpetbag. It was thus she found it. The napkin.

“Tom, ‘ow did you come by my napkin?”

She kept her voice carefully flat.

Thomas looked at her over the head of the child on his knee.

“Why Tildy,” he chided. “You must be mistaken. The Lord sent me a loaf of warm ‘ome-made johnny cake when I was hungry. That’s the Lord’s napkin.”

Tildy raised her chin.

“No it ain’t. It’s my napkin!”

For it unmistakably completed the set of hand-spun Irish linen her mother had cherished all the way from England, across the plains. The same original tatted edging—

Once again Tildy clapped a hand to her mouth. Of course. The Nephite—That was why he had taken the napkin-wrapped bread! Not to feed himself, but Thomas in England!

***

Sometimes Tildy’s daughter, even though she’s now an old, old woman herself, climbs up to the attic of her daughter’s house and rocks the squat wooden cradle made in the Order’s own cooper shop. She uses the cradle as a sort of chest, and sometimes she dreams over its treasures one by one. Most precious of all is a certain linen napkin, somewhat yellowed and frayed, perhaps, but still outlasting time—perhaps outlasting even those Three who “did go forth.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue