Articles/Essays – Volume 23, No. 2

Hearkening Unto Other Voices | Robert L. Millet, ed., “To Be Learned Is Good If…”

When I first picked up a copy of To Be Learned Is Good If . . . I assumed that the implied remainder of the title would be a continuation of Jacob’s famous statement about hearkening unto the voice of God. Having read the book, though, I now believe that some of the twelve authors would prefer to append the words . . . If They Hearken unto Our Way of Thinking.

This collection of essays addressing “controversial religious questions” bristles with intolerance of diverse views of scripture, faith, and history. We are told that Christians outside of Mormonism are “seal[ed] from any meaningful understanding [of] the scriptural records” (p. 116); that their theology is “false and absurd” (p. 68), “unscriptural, foreign to the spirit or content of the New Testament, and doctrinally untenable” (p. 70).

Under greater criticism, though, are the authors’ fellow Saints, the “self-proclaimed intellectuals” (p. 212), who are “grievous wolves among us” (Preface). If we are “hesitant to ‘read into’ the biblical record what we know from modern revelation” we are guilty of “naivete” and “irresponsible scholarship” (p. 61). If we have faith in a “religious phenomenon,” we must accept its “historicity” and believe it to be “an objective and discernible occasion” (p. 191). If we believe that Joseph Smith placed any of his own doctrinal understanding “into the mouths of Benjamin or Alma or Moroni,” we thereby charge the Prophet with “deceit” and “fabrication” (p. 67), strip the book’s “teachings and core message” of “their divine warrant as God’s revelation” (p. 220), and “threaten to decoy the . . . Saints from the saving substance of the gospel” (p. 221). “Revisionist” historical models are not only incorrect, they are dangerous (chs. 1 and 13), and their authors will “answer to God himself for their actions” (p. 6).

Even when the authors do not directly attack alternative views, they find no room for them: Our history must always promote faith. The JST is a pure restoration of lost truths, not inspired commentary. The doctrines of the Church have been taught in all ages exactly as we have them. There is no discrepancy between recitations of the First Vision. Biblical criticism, properly understood, contradicts none of the cherished traditional LDS interpretations. All scriptural stories are literal. The Bible is best understood not by its own internal evidence but by interpretations provided by modern Church leaders. With a few exceptions, these essays neither produce nor allow new insights or fresh perspectives.

An uncomfortable tension between the desire for academic respectability and the disdain for “temples of modern . . . learning” (p. 210) pervades the book. In the preface, editor Robert Millet lauds his authors as “men who have received aca demic training in some of the finest institutions of higher learning in the United States” while simultaneously decrying the “worldview of Babylon” and the “cynical secular world” (pp. ix-x). Continuing the self-contradiction in his first essay, “How Should Our Story Be Told?”, Millet writes, “The crying need in our day is for academically competent Latter-day Saint thinkers to make judgments by.. . the Lord’s standards” (p. 4, emphasis added). When did the Lord start requiring worldly training for writers of “sacred history” in the mode of the Book of Mormon, which he holds up as the “perfect pattern for the writing of our story” (p. 2)?

Both Millet (pp. 188-89) and Monte Nyman and Charles Tate (p. 78) praise modern criticism for what it can teach us about the Bible but then fail to cite any such enlightening discoveries and even lambast the conclusions reached by such methods. Michael Wilcox says that when we turn our analysis from historical or literary figures to the prophets we must leave behind “our leanings to the worldly definition of .. . scholarship” and use “the Lord’s emphasis” (p. 210). But Stephen Ricks and Daniel Peterson spend an entire essay (pp. 129-47) analyzing acts of prophets (such as Moses’ use of Aaron’s rod or Joseph Smith’s mystical means of finding lost items) by the standards of definitions of “magic” as used in modern religious studies scholarship.

Inter-essay conflict is also abundant (though usually not regarding the central themes of the essays, which are quite homogeneous in their conclusions). Millet, for example, in one place down plays the influence of the Gospels’ authors on those writings’ final form (p. 199) but in another tells modern historians how to write inspired sacred history in the scriptural model (pp. 1-8). He quotes Robert Matthews’s statement that the Bible “was massively, even cataclysmically, corrupted before it was distributed” (p. 192), while Nyman and Tate spend thirty-eight pages defending the proposition that “there is absolutely no reason not to believe in the truth of the Bible and its message” (p. 79). Louis Midgley says that the “Book of Mormon claims no immunity from historical criticism” (p. 223), while Wilcox asserts that worldly criticism of “light and truth revealed through the . . . prophets” puts us in the foolish position of “judging, commenting on, and counseling an infinite . . . Deity” (p. 210).

My last criticism of the book as a whole is a lack of specificity in its denunciations: “Some seek to suggest naturalistic explanations” (p. 3); “Some are enamored with the use of. . . theoretical models” (p. 3); “some self-serving historians grovel for ‘truth’ that would defame the dead” (p. 5); “Many enemies of the Church have accused … ” (p. 18); “a few Latter-day Saints are busy reinterpreting . . . the Mormon past” (p. 219; emphasis added to all quotations). Midgley caricatures the views of LDS historians without citing them a single time (pp. 225-26). Surely those “grievous wolves among us” (p. ix) should be clearly identified for Church members. “Note that man,” wrote Paul of the rebellious, “and have no company with him, that he may be ashamed” (2 Thes. 3:14). (Paul continues his letter with other advice that could well be heeded: “Yet count him not as an enemy, but admonish him as a brother.”)

Let me now comment on a few aspects of individual essays.

LaMar Garrard’s paper on the tradition of integrity in the Smith family and Bruce VanOrden’s on the compassion of Joseph Smith strike me as useful works, free of the offense and narrowness of some of the other chapters.

Ricks and Peterson present an interesting discussion of the appropriateness of the word “magic” for events in the Bible and in the life of Joseph Smith. They conclude that works performed by the true power of God should never be called “magic.” Of course, objectively determining what power was actually at work raises obvious difficulties, but this article is a worthwhile contribution to this ongoing discussion.

The essay by Louis Midgley is, for me, the most frustrating. He appears to make remarkable concessions: “Since the Book of Mormon . . . claims to be authentic history, it follows that faith is necessarily exposed, at certain points, to disconfirmation by the work of historians” (p. 223); and, “the Restoration message is true if—and only if—the Book of Mormon is an authentic ancient history. And clearly these questions can be tested, if not settled, by the methods of the historian” (p. 224).

But while Midgley seems to thus lay his faith on the altar of historical criticism (a move that would rightly be condemned by several of his fellow writers in this book), he in reality does no such thing. He removes some questions from historical scrutiny altogether when he says, “Some things about the past are simply true; otherwise our faith is in vain” (p. 223). And, despite his previous intimations, he never puts any particular point of history on the table to examine what historians have said of it. He thus displays no evidence, beyond simple assertion, of truly believing that important historical events and the faith that is founded on those events “might possibly be false” (p. 223).

Midgley also says we should “welcome” challenges to the authenticity of the Book of Mormon and to the Joseph Smith story (p. 224). But he never seriously discusses the validity of any such challenges and refers to those who raise them as “savants,” “cultural Mormons,” “marginal members who . . . can neither spit nor swallow when it comes to the gospel,” “not sound guides,” and “the rebellious” (p. 225-26).

Midgley shows himself to be incapable of mythological thinking or of seeing as genuinely faithful any scriptural hermeneutic other than the strictly literal. The Book of Mormon is either historically true or it is “fiction.” “The question of the historical authenticity of the Book of Mormon is necessarily the initial question. .. . A negative . . . decision about the initial question closes the door to a faithful response” (pp. 223-24). He is obviously aware that there are Church members who are not restricted to such a dichotomy, but he gives them no fair hearing. His unyielding demand for absolute historicity reminds me of Northrup Frye’s comments:

Someone recently asked me, after seeing a television program about the discovery of a large boat-shaped structure on Mount Ararat with animal cages in it, if I did not think that this alleged discovery “sounded the death knell of liberal theology.” . . . This attitude says, for example, that the story of Jonah must describe a real sojourn inside a real whale, otherwise we are making God, as the ultimate source of the story, into a liar.

It might be said that a God who would deliberately fake so unlikely a series of events in order to vindicate the “literal truth” of his story would be a much more dangerous liar, and such a God could never have become incarnate in Jesus, because he would be too stupid to understand what a parable was. (The Great Code: The Bible and Literature [New York: Harcourt Brace Jovonovich, 1981], pp. 44-45)

I began this review by suggesting an alternative ending to the title To Be Learned Is Good If. . . . Perhaps it would be better to replace the title entirely, as the book ultimately conveys no belief in the goodness of learning, or, for that matter, of faith, when either of these leads the seeker outside the narrow con fines of the authors’ definition of “truth.”

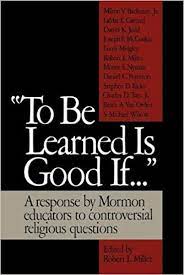

To Be Learned Is Good If . . . edited by Robert L. Millet (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 242 pp., $11.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue