Articles/Essays – Volume 22, No. 1

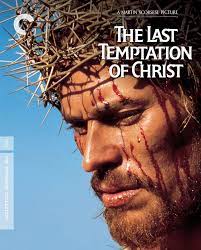

Humanity or Divinity? | Martin Scorsese, dir., The Last Temptation of Christ

Outside the San Francisco theater where we saw The Last Temptation of Christ, Christians paraded with guitars, bullhorns, sandwich boards, and placards (some in Cantonese) protesting the blasphemous portrayal of their Lord and Savior. Anti-semitic signs accused Lew Wasser man, the Jewish chairman of MCA (parent company of Universal Studios), of persecuting Jesus. One Baptist minister labeled the film as filthy and ugly, predicting that it would bring God’s fiery judgment down upon America. Among those defending the filmmaker and the First Amendment rights of theaters and viewers to choose what movies to see, were men dressed as nuns identified as the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, marching with signs that read “Thou shalt not censor.”

Inside the theater, the tone was more subdued. Having our bags checked by police at the door somehow gave us a sense of having entered an important place. At least there was a quiet anticipation that seemed reverential. We were curious to see what had upset so many people (though we realized that many of the protesters had not even seen the film).

The film began with a disclaimer that it was based upon the fictional writing of Nikos Kazantzakis and not upon the Gospels, themselves written many years after the events they describe.

When Jesus, played by Willem Dafoe, comes on the screen, he is unsure of his identity. As a carpenter, he builds crosses for the Romans on which his fellow countrymen are crucified. His friend Judas Iscariot criticizes Jesus’ acceptance of the Roman occupation. Jesus answers that he is angry at the injustices but that when he begins to speak words of anger, he inexplicably ends up speaking words of love. Jesus is also troubled by voices. His mother suggests that he have them exorcised if they are of the devil, and he replies that they may be exorcised if they are of the devil. But, what if they are from God? Can one exorcise God?

In the Kazantzakis novel, these voices resulted in a seizure, and caused Jesus to break his betrothal to Mary Magdalene (played by Barbara Hershey in the film), shaming her in such a public way that she became a prostitute. Though the situation is not clearly drawn, the film picks up this story as Jesus visits a house of prostitution, wishing to speak to Mary Magdalene and ask her forgiveness. This is one of the scenes that had offended the fundamentalist critics outside the theater as we and Jesus watch Mary in the brothel. Jesus is waiting to be alone with her and apologize, an apology she rejects.

The movie is good at showing Christ’s uncertainty and anguish, but it fails to show him as a charismatic leader and teacher. Since the story is not taken directly from the Gospels, the film portrays Jesus as a man of his times, not someone who would attract a devoted following, not someone sure of his mission.

What really seems to test the forbearance of the crowd outside the theater is the dreamlike temptation Jesus experiences while on the cross. Christ’s last temptation is an enticement to live a normal life. While dying on the cross he alone sees a small girl who invites him off the cross and explains that he no longer has to go through the extraordinary agony, suffering for the accumulated sins of the world. He is free. She leads him from the executions on Golgotha toward a wooded area. A wed ding party appears and Jesus asks, “Who’s getting married?” The young companion replies, “You are, Jesus.” We see Mary Magdalene, beautiful in white. Jesus embraces her; we see her pregnant with Jesus’ child. However, she dies in childbirth, and Jesus takes Mary and Martha to wife. As the young female guide tells him, all women are one, only different faces.

Jesus ages before us, fulfilled, with a happy family of children. Then, as he lies dying, he meets Saul of Tarsus who tells him that he is not the real Jesus. The real Jesus died on the cross and gave justification to Paul’s Christian evangelism. At this point, Jesus recognizes his greater role and, in an act of free will, chooses crucifixion. As he returns to the cross, we learn that the young guide is really Satan presenting one last spellbinding temptation for Jesus to overcome. Since Jesus does not succumb, we may understand that Jesus is “one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet [is] without sin” (Heb. 4:15).

It is this temptation of sensual love, marriage, and children that causes us to see the truly human side of Jesus. And it seems to be this demonstration of humanity that offends the protestors. Perhaps we are more comfortable thinking of Jesus as divine, above temptation. It was this instinct that led to the third century heresy, called Docetism, which held that Jesus was not really human, but only appeared to be. The orthodox Christian doctrine of incarnation, eventually set down in the fifth century at the Council of Chalcedon, de fined Jesus as having both humanity and divinity within his nature.

If there was an anticipation of lust and scandal at the beginning of the film, the end left us with reverential understanding. Martin Scorsese seems a very religious man who has presented the human side of Christ with the uncertainty and anguish that is part of being human. This is a Christ humans can relate to, one who understands mortality.

The Last Temptation of Christ, a film by Martin Scorsese, produced by Universal Studios, 1988, and based on a novel of the same name by Nikos Kazantzakis (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue