Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 2

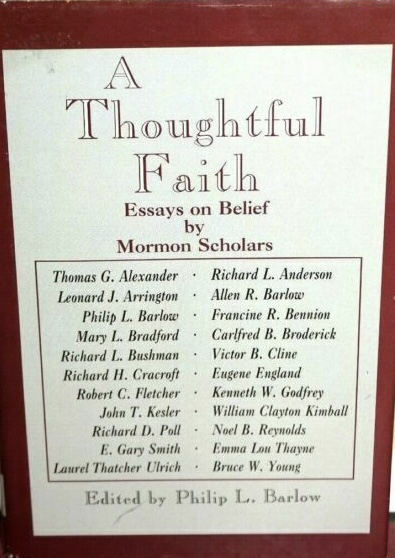

Seasoned Saints | Philip L. Barlow, ed., A Thoughtful Faith: Essays on Belief by Mormon Scholars

I discovered early in my scholastic career why a Mormon would never produce great literature. (A good Mormon, that is.) The reason was simple, expounded with eloquence and authority by my BYU “Intro duction to Poetry” teacher. He, along with W. B. Yeats, believed personality and char acter to be mutually exclusive modes of being: You could not be possessed of both at once.

Character in its most potent manifestation was an LDS businessman turned General Authority, all suited up in the armor of God and narrow-lapeled worsted wool. True personality, on the other hand, was represented by that moral sloven Dylan Thomas, from whose pen flowed high poetry and praise of God not despite, but because of his eccentricity, flawed char acter, and heavy drinking. A series of such examples convinced me that the ways of God spell ruin for the aspiring artist or intellectual. In striving to obey God’s laws, his or her individuality would be lopped off little by little that she or he might conform to more universal standards of godliness. Thus, the closer the faithful came to living a godly life, the more alike they would become. Losing your life to gain it meant trading individuality for eternity in the company of your duplicates.

Some years later, upon lowering my aspirations from poetry to godhood, I dis covered the fallibility of poetry teachers. Phil Barlow’s collected statements of faith by Mormon scholars would have saved me considerable mental fumbling as well. There is nothing depersonalized or’ duplicate about these twenty-two seasoned saints or their essays. They are, in fact, startling in their differences.

Philip Barlow completed his master’s in theological studies at the Harvard Divinity School and is currently working toward a doctorate degree from Harvard in Ameri can religion and culture. His own essay expounds “fifteen thoughts,” clearly articles of belief, which interweave and build into a “spiritual framework” and profoundly moving final profession of faith in the Church.

Poet Emma Lou Thayne plots her evolving relationship to the Church around a metaphor, childhood memories of the big swing at their mountain cabin, in prose which is, as Barlow observes, half-poetry.

In contrast, Eugene England reasons with his readers, carefully guiding them along a course “From Hope to Knowledge to Skepticism to Faith” with enough conversational first and second person plurals to have me checking my room for other members of the congregation.

Allen R. Barlow, an electronics engineer and physicist, writes a short story. Carlfred Broderick, noted marital and family therapist, charts his spiritual odyssey with wry humor and wonderful candor. He begins, “Many a night as I grew up I lay awake listening to my mother and step father argue in their bedroom, which was separated from mine only by a thin wall. As I remember, two topics were the major themes of their sometimes heated discussions. One was me” (p. 86).

In ideas, as in style, form, and tone, these essays differ markedly. In fact, some clearly contradict each other in their assumptions and major premises. For instance, historian Richard Bushman records his continuing quest for the “specific, empirical, historical” evidences and arguments which would justify belief (p. 23). “That was why I liked Nibley: because he put his readers over a barrel. I wanted something no one could deny” (p. 25). Hearing the Grand Inquisitor passage in The Brothers Karamazov read at a young adult discussion group redirected his thinking.

The sentences that stuck with me that time through were the ones having to do with looking for reasons to believe that would convince the whole world and compel everyone to believe. That was the wish of the Inquisitor, a wish implicitly repudiated by Christ. The obvious fact that there is no convincing everyone that a religious idea is true came home strongly at that moment. It is impossible and arrogant, and yet that was exactly what I was attempting. When I sought to justify my belief, I was looking for answers that would persuade all reasonable men. .. . In that moment in Cambridge, I realized the futility of the quest (pp. 24-25).

Francine Bennion, on the other hand, describes an opposite progress toward deeper faith. From a point in her life when she felt “indifferent to matters of intellect” and what seemed “academic game-playing” (p. 104) she moves to the vantage point from which she asks, “Who can say that faith and reason are separate categories?” and asserts our profound need to establish “a large and reasonable context for looking at what scripture is, what humans are, who God is, what life is for, and . . . for understanding not only answers, but also the questions” (p. 114).

Overall, these stimulating essays substantiate C. S. Lewis’s admonition in Mere Christianity. “If you are thinking of becoming a Christian, I warn you you are embarking on something which is going to take the whole of you, brains and all. . . . God is no fonder of intellectual slackers than of any other slackers” (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1943, p. 75).

The contributors, though heavily weighted with historians, also include poets, literary critics, professors, writers, attorneys, psychologists, philosophers, theologians, and a scientist or two: Richard D. Poll, Richard L. Bushman, John T. Kesler, Kenneth W. Godfrey, Thomas G. Alexander, Eugene England, Carlfred B. Broderick, Francine Bennion, E. Gary Smith, Robert C. Fletcher, Emma Lou Thayne, Victor B. Cline, Allen R. Barlow, Mary L. Bradford, William Clayton Kimball, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Noel B. Reynolds, Leonard J. Arrington, Philip L. Barlow, Bruce W. Young, Richard L. Anderson, and Richard H. Cracroft. Most of these essays are the length of a modest sacrament meeting talk.

In response to the editor’s invitation “to publicly articulate the reasons for their steadfast belief in Joseph Smith’s prophetic role and in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ” (p. xii), some offered essays dating from, as early as 1966, reprinted from Sunstone or DIALOGUE articles, a BYU devotional address, and even, in the case of Richard Poll’s now classic essay distinguishing between Liahona and Iron Rod saints, a sacrament meeting talk. Others,

in the spirit of the New Testament injunction to “be ready always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in you with meekness and fear” (1 Pet. 3:15), wrote expressly for this collection spiritual autobiographies of such honesty, intimacy, humor, and per sonal wisdom that they would never pass Correlation.

Actually these essays provide a wonderful antidote for those of us who have over dosed on abstract speculative theology and the indignation industry which sometimes flourishes in submissions to DIALOGUE and Sunstone. They are illuminating, affirmative essays, the best testimony meeting you are ever likely to attend.

A Thoughtful Faith: Essays on Belief by Mormon Scholars compiled and edited by Philip L. Barlow (Centerville, Utah: Canon Press, 1986) xiii, 310 pp., indexed, $14.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue