Articles/Essays – Volume 20, No. 4

Reflections from Within: A Conversation with Linda King Newell and L. Jackson Newell

After serving five and a half years, Linda and Jack Newell step down as editors of DIALOGUE as this issue goes to press, turning the editorship over to Kay and Ross Peterson of Logan, Utah. Following is an interview with them conducted by Lavina Fielding Anderson, associate editor.

Lavina: What has been your history with DIALOGUE? When did you first encounter it and what were your ties with the journal before 1982?

Linda: We read about the founding of DIALOGUE in Time magazine in 1966 and spirited a check off just in time to get Volume 1, No. 1. We haven’t missed an issue since. With the exception of Jack’s essay in Winter 1980, how ever, neither of us had written for DIALOGUE or otherwise served the journal until we assumed the editorship.

Lavina: Did you apply for the position?

Linda: Oh, no! Dick and Julie Cummings invited us over for dinner in the fall of 1981 and asked if we would like to be nominated. We were honored but declined. We didn’t feel qualified to succeed Mary Bradford, and we didn’t know where we’d find the time to edit a major publication anyway. We enjoyed the Cummings and their hospitality but didn’t give their suggestion serious thought.

Lavina: Then what?

Linda: Fred Esplin and Randy Mackey, co-chairs of the editor search committee, came by one Sunday afternoon early in 1982 and told us we had been chosen! We were stunned. But by then Valeen Avery and I thought we were only a few months from finishing our book, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith, and Jack had just received word of his promotion to full professor. On the crest of these events, we were foolish enough to try anything. We have always worked quite well together and thought we would enjoy serving together as editors. After a week of reflecting, we said “yes,” on the condition that you serve with us, Lavina.

Lavina: What were your initial objectives?

Jack: To assure DIALOGUE’S continuing editorial independence, to publish on time, to double the readership, to build a one-year reserve fund, and to do it all with a touch of class. We wanted everyone associated with DIALOGUE to be proud of it. It was clear from the outset that these goals were highly interdependent.

Lavina: How did you start?

Linda: With good fortune. Those who chose to serve with us are remarkably talented and diverse people. The entire Executive Committee -— and most everyone else who started with us—has stayed together for five and a half years through this final issue under our editorship. And many other able people, like Kevin Jones and Linda Thatcher, have joined us along the way. I doubt that we will ever enjoy such esprit with a group again.

Lavina: How do you account for this camaraderie?

Linda: Editing DIALOGUE requires more knowledge and skill than any one or two people possess. We learned quickly to delegate and trust each other’s judgment within the staff. And on the crucial editorial and policy decisions, we all learned to express ourselves forcefully and listen to each other carefully. Ten or twelve people participated in the biweekly staff meetings held in our living room on Tuesday evenings. We often debated furiously, but strong differences can bring people closer if genuine good will prevails. The members of our editorial group have profound respect for one another. Jack and I have often disagreed, too—I tend to be more intuitive, and Jack is more analytical. It became increasingly evident to us as we went along that these two perspectives complement each other, particularly when it comes to tough editorial decisions.

Lavina: Were the early months your hardest?

Linda: Moving the journal from Washington, D.C., and a snafu with our first typesetter meant that we were almost a year behind. Mary’s last issue, Spring 1982, came out in the summer. We didn’t get the summer and fall issues out until January 1983, but by then we were rolling. In the next twelve months we published five more issues. This year we reached our goal of mailing each issue on the first day of the quarter: the winter issue goes into the mail on 1 December. You are as responsible for that as anyone, Lavina. Our business manager, Fred Esplin, says, “You’ve got to have somebody who’s a stickler for deadlines,” and that’s been you.

Lavina: I accept the compliment. But I think we need to give credit where it’s due: to our group of volunteer editors, proofreaders, and typists. Their work is all-important, but it never shows when it’s done right. Proofreading in particular has to be the ultimate invisible task. We proof everything five times in manuscript, galleys, and page proofs, and errors still slip through. When they do, we feel embarrassed and try to do better next time. Jerilyn Wake field, who teaches school in Tooele and who won one of our writing prizes for her essay about adopting her son as an unmarried woman, has been with us from the start—proofreading after J. L. is asleep at night, and occasionally adding “Grief!” in the margins of particularly outrageous sections.

Don Henriksen, our typesetter, is a phenomenon. He’s a ballroom dancer six nights a week, divorced, in his fifties, with a dashing moustache. He started in the typesetting business as a boy when it was all hot lead. Today he still sets hot lead in a workshop in his basement. He’s worked nights and weekends to inch us up on the schedule a few days at each issue. He says he can hear by the rhythm of the matrices of type falling whether he’s hit the wrong key or not. He’s amazingly accurate.

Susette Fletcher Green is another of the treasures who has been with us from the beginning. She responded to our questionnaire and said she’d like to volunteer. She’d spent the last thirteen years raising her four children—she added a fifth during the DIALOGUE years—and teaching in volunteer pro grams at school. She turned out to be a natural-born editor and has been co-associate editor for the last couple of years. She’ll stay on the new team, and I feel immense confidence in turning the copy editing over to her.

Linda: Others have played a key role, too. Daniel Maryon, our assistant editor and office manager, makes sure everyone gets everything they are supposed to, including our subscribers—he sees that they get their issues and their renewal statements. Incidently, Dan is one of many Maryons who have worked for DIALOGUE over the past five years. He came to work in 1983, first as a part-time office person then full time when his sister Annie Maryon Brewer left DIALOGUE to begin a career as a social worker. His mother, Pat, two more of his sisters, and his wife, Dorothy, have all worked in the office from time to time. His father, Ed Maryon, provided the art for our Spring 1984 issue.

Lavina: Jack, how do you see DIALOGUE as a part of the larger stream of Mormon culture?

Jack: Since converting to the LDS church from Methodism twenty-five years ago, I have been both exhilarated and perplexed by my “chosen” religion. I have been exhilarated by the sense of community it engenders, the sense of purpose and hope it conveys to its adherents, and by the boldness of its claims and practices. It is a young religion, still energetic and sometimes brash. To me this is appealing. On the other hand, these same qualities have their negative sides. What members experience as community sometimes comes across as cliquishness to outsiders. Energetic and brash can read powerful and arrogant if you’re not part of it. And our bold claims sometimes look silly to others. Some of our cultural practices are silly. It is easy for Mormons to see ourselves in the images we and our church promulgate. But it’s particularly difficult for us to see ourselves as others do, because of our strong cohesiveness and, in Utah, our numerical dominance. One of DIALOGUE’S greatest contributions over the last two decades has been to bring a measure of objectivity to our perceptions of ourselves and our world. This, of course, is the stuff of serious scholarship everywhere.

Lavina: How objective do you think DIALOGUE has been under your editorship?

Jack: True objectivity is probably never realized in this world. It involves listening carefully to divergent views, seeking verifiable information, and treat ing alternative explanations of events, actions, and motivations seriously. It also means treating those who hold differing views with respect. This involves listening to them, weighing their evidence without bias, and responding to what they have actually said or actually believe rather than ascribing motives (always a risky and flawed endeavor) or exaggerating their position to make our response more credible. As editors of DIALOGUE, we may not always have been objective, but we have tried to put this philosophy into action—to be as objective as we can make ourselves.

Lavina: You and Linda have been criticized by some for failing to devote comparable space to more traditional interpretations of history and doctrine. Are these criticisms justified?

Jack: Some believe DIALOGUE is not true to its name unless the whole dialogue takes place within DIALOGUE. I don’t see it that way. This journal makes dialogue possible by providing a forum for scholarship and responsible essays that could not be brought to the attention of serious-thinking Mormons through any other publication. Let me give an example. We recently published Harris Lenowitz’s article “The Binding of Isaac: A View of Jewish Exegesis” (Summer 1987). This piece was originally presented to the B. H. Roberts Society in the spring of 1986. The other two speakers that night, BYU professors Kent Brown and Kent Jackson, defended a rather traditional Mormon view of scripture. Their papers were well-conceived and well-crafted, but in our judgment they presented material with which DIALOGUE readers and other well informed Latter-day Saints are already familiar. Put differently, other publica tions and other occasions have provided and will offer Latter-day Saints access to Brown’s and Jackson’s perspectives. Thus, DIALOGUE made dialogue possible for our readers by providing a forum for another view—the Jewish view—of scripture. If I thoughtlessly laid my Bible on the floor in the past, I haven’t done so since encountering Lenowitz’s sobering description of his visit to the LDS Institute. His article also precipitated a number of conversations with friends about what we regard as appropriate respect for a sacred book. That’s DIALOGUE making dialogue possible. It doesn’t all have to happen within our pages, but it should happen because of what we publish.

Lavina: What has been your editorial philosophy? What values have governed your editorial decisions?

Jack: DIALOGUE should publish the finest scholarship and literature available in and around Mormonism today. Throughout history and across cultures, “official” literature and art are rarely distinguished. Great artists and great writers struggle to help us confront reality, to become aware of our facile assumptions and to see the paradoxes in our comfortable conformity .. . or the irony in our self-righteous rebelliousness. It’s like wearing a hair shirt, but every culture and every institution needs to look itself squarely in the eye and deal with uncomfortable questions from time to time. It’s the only way we can stay healthy. If we lose the capacity to do this for ourselves, then only outsiders will be left to do it. But we never hear them well; we’re too defensive. It’s human nature.

Lavina: Do you see DIALOGUE, then, as an expression of the loyal opposition?

Jack: That’s not a concept Mormons have entertained, but there is some merit in it. I like the notion because it implies no position on the ideological spectrum from liberal to conservative. It simply assumes the airing of other perspectives. DIALOGUE does have a liberal bias, however, if that means a preference for free and responsible thought. But we must remember that free and responsible thought sometimes finds in favor of traditional interpretations of history and even the wisdom of official proclamations.

Lavina: Then why does DIALOGUE seem to be feared by some LDS church leaders?

Jack: Among the leaders of the Church there are those who believe that free expression will breed error. There are other leaders, however, who see free expression as an essential creative influence or as a powerful corrective for the occasional inhumane implementation of a well-intended policy. That’s fine. My views happen to correspond with the latter, but as long as both kinds of leaders are present—and their conflicting perspectives are aired in official circles—we have no reason for alarm. In any event, DIALOGUE does not exist to please officials. It does not exist to please anyone. It is here to be considered, not to be loved. Paradoxically, that’s why some of us have loved it for twenty years!

Lavina: How do you blend the intellectual independence you love with the kind of institutional loyalty that is necessary to make the Church work?

Jack: I don’t. Intellectual independence and institutional loyalty are contradictory terms. Our ultimate loyalties should be to principles, not to institutions or individuals. In the case of the Church, our loyalty must be to the principles of our religion. I’m talking about truthfulness, forgiveness, repentance, unconditional love, and mercy for those who hunger, or grieve, or bear heavy bur dens. The Church is done a disservice (and is sometimes even done in) by those who substitute loyalty to the organization or to individuals within it for loyalty to its principles. So again we come to one of these paradoxes: intellectual independence does serve the institutional church by asking whether its means, its policies, and its practices are consistent with its highest ideals.

Lavina: How did you come to hold these views, Jack? Did you bring them into the Church with you as a convert, did they develop somewhere along the way, or have they emerged from your association with DIALOGUE?

Jack: I have a fairly optimistic view of human nature. I believe that, if trusted and respected, the vast majority of people will do the right thing on their own. Despite forty-eight years of knocks and bumps, I still believe this. I simply don’t accept the old adage that an idle mind is the devil’s workshop. This idea suggests that people are inherently devious and will do wrong unless we can find some way to stop them. Prison wardens may be excused for this assumption, but it is unbecoming to others, especially those in religious organizations. My beliefs about the interplay of individuals and institutions, and the relation ship between church and religion, have their roots both in my home and in my education. As a graduate student, I was steeped in the history of the European Enlightenment and the American Revolution before I joined the Church. I was naturally attracted, therefore, by the Mormon doctrine of free agency. I believed then and I believe now that the purpose of religion is to hallow enduring, even redeeming, ideas and principles. Churches are created to teach these doctrines for the good of the individuals who embrace them and ultimately, we hope, for the benefit of society. Force and pressure and guilt have no place in religion. When the Church lapses into these tactics, it makes a mockery of our doctrines and of free agency. I suppose I have spoken and written more about this problem since we have edited DIALOGUE, but the concern goes way back in my history. Words are only words, however. The persistent task is to live by the principles we espouse.

Lavina: How has DIALOGUE affected your lives?

Linda: It has caused us to reflect deeply on what we believe, and it has certainly educated us in a lot of important ways. It has also kept us active in the Church. Since our marriage twenty-four years ago, we have been Southerners, Yankees, Midwesterners, and Westerners, having resided in five states other than Utah. In three of those places we lived in small branches, one in Appalachia with a membership so poor that some members came from homes with dirt floors and children came to church with no shoes. In every place we lived before moving to Utah in 1974, we watched people with diverse economic and educational backgrounds and from across the political spectrum work together in the Church. Everyone was needed, and differences were left outside the chapel door—allowing us all to serve in a single effort. That’s not to say that everything went smoothly or that everyone always got along, but it was un thinkable that someone’s religious commitment could be suspect because his or her political views were liberal or conservative.

But from Salt Lake came rumblings in the form of conference talks, statements from Church leaders, and rumors that implied that “good” members of the Church couldn’t be Democrats, or believe in evolution or women’s rights, or be curious about their history—never mind that they drove forty or a hundred miles round trip to Church twice a week and held down three or five callings. Without DIALOGUE it would have been easy to conclude that we were simply oddballs who didn’t have a place in the Church. But the articles in the journal kept reminding us that we weren’t alone and we weren’t even that odd, and that commitment to the principles that hold the religion together has little to do with one’s political philosophy or scientific knowledge. Having edited DIALOGUE for these years, we’re all the more convinced of the beneficial part the journal plays in the lives of thousands of other members.

Lavina: But isn’t DIALOGUE detrimental to some?

Jack: Perhaps a few, but under ordinary circumstances, we should not shield people from new knowledge. After all, part of maturing as a person and as a Christian is learning to reconcile ourselves with imperfect institutions and an imperfect human race. Members who understand our tortured past may be much more understanding of our imperfect present. Perhaps this is the mean ing of the phrase “we cannot be saved in ignorance.” And DIALOGUE isn’t designed to appeal to everyone. Those who think the journal might be harm ful to their religious faith should not read it.

Linda: People choose to leave the Church for a variety of reasons. In the years we have edited the journal, we have had only one person write and say they were leaving the Church because of DIALOGUE. On the other hand, we get many letters from people who believe DIALOGUE has a positive effect on their religious life. Our reader’s survey (Spring 1987) bears this out. Of course, we also hear from people who have become disillusioned because of a Church policy, the official or private pronouncements of Church leaders, or the behavior of a local leader.

Some readers questioned our wisdom in publishing Michael Quinn’s article, “LDS Church Authority and New Plural Marriages, 1890-1904,” on post-Manifesto polygamy (Spring 1985), because of the sensitive topic. Al though no one responded to the article through a letter to the editor, the subject often came up in conversations. Many who are descendants of post Manifesto polygamous marriages are immensely grateful to DIALOGUE for putting the issue in historical context. Others were relieved that their progenitors had acted in good faith within a non-public policy, rather than through apostasy. Some found the article helpful in writing family histories and in understanding the context of post-Manifesto marriages. A few felt that, although they had been personally enlightened by the piece, we should not have published it, either because “the brethren” would be inflamed or because it might shake someone else’s faith (but, interestingly, not their own).

Lavina: Why is editorial independence an issue?

Jack: Independence is always an issue when scholarship, literature, and art are your purpose. Authentic scholarship can’t exist without it. But editorial independence was an issue for us for two additional reasons. First, the journal was coming to Salt Lake City for the first time, and some feared that the Church would try to apply pressure here that it would not try elsewhere. Second, the journal’s financial base was in the black but still tenuous. We didn’t want it to be vulnerable to the influence of potential donors. By active fund-raising efforts and by increasing circulation, we hoped to build up the journal and insure its editorial integrity.

Lavina: Have your objectives in fund-raising and circulation been realized?

Linda: We now print 5,300 copies of each issue, an increase of 2,000 since 1982. The chief satisfaction here is not financial, although it has helped to balance the books. The real satisfaction, of course, is that more people are reading the journal and therefore considering the ideas of our authors and artists. Writing is the hardest work I know—so the greatest compliment authors enjoy is to have others consider the fruits of their labors.

Lavina: And the fund-raising?

Linda: We now have a modest reserve fund that protects us from the seasonal highs and lows of contributions and subscription renewals. But we are far from paying adequate wages to the three or four salaried staff members. The journal has a stronger circle of contributors—both major and minor—on whom it can depend; but dollars in the bank are never insurance for any journal or any individual. DIALOGUE’S best insurance for the future is to continue to merit the support of its writers, readers, and contributors. Publishing on time, issue in and issue out, has been one of the achievements of this editorial team in which we take great satisfaction.

Lavina: Were the concerns about pressures from the Church warranted?

Linda: That depends on how you look at it. No Church official ever contacted us personally or tried directly to influence our editorial decisions. But there has been at least one indirect attempt. In 1983, about a year into our editorship, several General Authorities launched an effort to intimidate a few of our writers as well as some who wrote for Sunstone.

Dawn Tracy, a reporter for the Salt Lake Tribune, eventually interviewed fourteen writers in four states who had been called in and questioned by their stake presidents at the request of a General Authority. Neither Jack nor I was questioned, but the director of correlation at that time, Roy Doxey, did try to contact our bishop, who happened to be out of town. He talked instead with the first counselor. (Jack, by the way, was serving as the other counselor at the time which may be why they didn’t feel a need to check on him.) I was in the Relief Society presidency, and the Sunday after he received the telephone call, the counselor sauntered up to me in the ward foyer with a huge grin. “All right, Linda, I want to know,” he said.

“Want to know what?” I queried.

“I want to know which general board you are being called to?”

I laughed, “What in the world makes you think I’m being called to some general board?”

“Well,” he said, “I got a call this week from church correlation, and he asked if the Linda Newell in my ward was the Linda Newell who was connected with DIALOGUE. I told him you sure were. He asked someone in the room for the file on you, then questioned me about your standing in the Church, and asked if you held a temple recommend. I gave him a good report.”

My initial distress over such a telephone call immediately melted into appreciation for my ward and the people in it. We have lived in that ward for ten years and, for me, it was enough to know of the confidence that counselor had in me and to feel the support and love from those who knew me best: my own ward members. This was something that I would experience in future difficult times.

Lavina: Are you referring to the action taken by Church leaders which prohibited you and Val Avery from speaking in church about your book, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith; and do you feel that that action had anything to do with your being co-editor of DIALOGUE?

Linda: Yes, to the first of your questions. I once more felt the quiet re assurance and supportive love from my neighbors and ward members during that period. As to the other question, I don’t believe the ban (which was lifted ten months later) had anything to do with DIALOGUE, although I have been asked that question many times. But because it occurred during our editor ship, it was natural that many subscribers sent words of encouragement and love during a time they knew was difficult for us.

Lavina: Returning to the previous question, what did you do when the writers were being called in?

Jack: We raised our voices in protest privately and publicly, as did Peggy Fletcher at Sunstone and a number of others—including many who were interviewed. I don’t know for sure why the campaign ceased, although attempts to limit free expression in our society always backfire when they are exposed. More recently, the Church has tried to prohibit its employees from writing for independent Mormon publications.

Lavina: Does this prohibition affecting Church employees bother you?

Linda: Absolutely. For one thing it’s difficult for DIALOGUE to achieve its desired balanced perspective when we don’t receive manuscripts from these people. For another, it bespeaks distrust of open discussion which is unbecoming of any organization that professes to seek and love the truth.

Lavina: Have you noticed any changes over the last few years in official Church attitudes toward independent publications and meetings that deal with scholar ship about the Mormon experience?

Jack: In the mid-1980s LDS leaders tried to silence some scholars—by inter viewing writers and banning speakers. Their efforts had little effect except to splatter bad publicity all over the newspapers. Switching strategies, the Church has since cut researchers off from key sources by severely restricting access to the archives. They are also making it difficult for Church educators to participate in independent scholarly gatherings, like the Mormon History Association’s annual convention or the Sunstone Symposium, by requiring the use of personal leave time and personal funds to do so. When BYU was up for re accreditation a year or two ago, an internal study reported that no administrators could write for DIALOGUE or read a paper at the Sunstone Theological Symposium. Given the number of administrators there, that limits the academic freedom of a lot of scholars. Seminaries and institutes are no longer supposed to subscribe to independent publications, and their faculty members are counseled to keep personal copies where students can’t see them. Also, no Church periodical can cite any article or quote any passage from unofficial Mormon scholarly publications. These are just examples, but you get the picture. As with the official nonrecognition that Leonard Arrington ever served as Church Historian, authorities would like to create the impression that certain things never happened or don’t exist. This is what I call “malignant neglect.”

Lavina: Why do you think church actions like the ones you have just mentioned occur?

Linda: I think that it results primarily from a misunderstanding of DIALOGUE’S purpose and the reasons why people write for DIALOGUE. AS the Church continues to expand its world-wide membership, Church leaders become increasingly burdened with problems ranging from the trivial to the monumental. More responsibility has to be delegated. As a result, middle-level bureaucracy has expanded to the point where Church leaders are more and more isolated. Being spared many duties and problems is certainly an advantage: but at the same time, the top leaders are deprived of the ideas, insights, concerns, scholar ship, and inspiration of some of the best minds in the Church.

Many of our writers feel that DIALOGUE is a vehicle for expression that can reach some of the members and perhaps even the leaders—”surely,” they say, “someone up there must read DIALOGUE.” My hope is that somewhere among those someones, there are a few who recognize the creativity in the ideas, the genius in the insights, the sorrow in the concerns, the faith in the scholarship, the love in the feedback, the hurt in the anger, and the God-given right to the inspiration.

General Authorities, whose time is extremely limited, sometimes assign someone else to peruse various books and periodicals for them. One such per son was employed in the Church Historical library throughout the seventies and into the eighties (but is no longer there). He often spoke of being on “special assignment” to do reading “for several of the brethren” and glibly showed off his work, which consisted of underlining controversial passages in DIALOGUE and other periodicals and books. I remember the sick turn of my stomach the time he showed me his marked pages. Clearly he was not focused on understanding concepts or information but on “exposing” scholars and writers, particularly historians. Passages of their work would then be read out of context by apostles, removing any real possibility for understanding.

Jack: We certainly have. We’ve received manuscripts for which different individuals or groups have campaigned very hard. At both ends of the spectrum, from apologists to apostates, there are a few who would use DIALOGUE for diatribe or character assassination. Fortunately, the people coming from these extremes nearly balance each other out. They all seem to think we should publish their ideas because they believe so strongly in their positions. What matters to us, however, is the thoroughness of authors’ research and the rigor of their logic—not how passionately they are committed to their point of view. Passion has its merits, but it doesn’t make up for shoddy scholarship or poor writing.

Lavina: Is space a problem? How many publishable manuscripts have you turned down simply because there wasn’t room to include them?

Jack: At the beginning of our tenure as editors, we budgeted for 128-page issues, but so many pieces worthy of publication came in that we continually published more pages than we had planned. As you know, there are about a hundred manuscripts on our logs at any given time. We are able to publish only 10 to 20 percent of these; some that we reject have real potential, so we understand why writers sometimes react in anger or frustration. But we expected this kind of heat. You simply try to develop a thick skin without letting it become an insensitive hide. This is one of the reasons the editorship should change hands every five years.

Lavina: What are some of your experiences in working with authors, Linda?

Linda: They really come in the good, the bad, and the ugly. Some authors, despite the numerous pleas to make all their changes before their work is type set, still try to rewrite at the galley stage, causing costly delays. On the other hand, one author in Canada drove his galleys down to be sure we’d get them on time. Then there is Mike Quinn—he just won’t quit. He kept refining his post-Manifesto polygamy article, not only at the editing stage and the galley stage but beyond. When we refused to make one last change, by jingo, he drove out to Don Henriksen’s and paid him $100 to change the final type!

Jack: Few people know of or appreciate the thoughtful consideration and earnest debate devoted to each article they read in DIALOGUE. For example, David Buerger’s two essays on the temple (the first was in the Spring 1983 issue and the second is in this issue) focus close to the core of the Mormon religious experience; consequently we felt an immense responsibility to assure a balanced tone and impeccable content. We were determined to be completely faithful to the documentary evidence, while avoiding unnecessary assaults on the sensitivities of temple-going Latter-day Saints. David has the ability to be reflective about his own work. He was cooperative, helpful, and resourceful throughout the long process of revising and editing. One of the hard decisions we made was to remove a passage-by-passage comparison of certain Masonic ceremonies with the published versions of the Mormon temple endowment. Our scholarly and intellectual training told us an author shouldn’t claim parallels without demonstrating them, but our own commitments and respect for both Mormons and Masons—after all, their ceremony is private and sacred, too—meant that we couldn’t leave some of the material in. This ethical dilemma precipitated earnest discussions among the staff that went on for months. In the end, we and David agreed to go with the documents as far as we could without violating the privacy rights of the two groups whose liturgy the article compares.

Linda: Oddly enough, the greatest number of reader complaints has been about Levi Peterson’s prize-winning spoof, “The Third Nephite” (Winter 1986). Members of the editorial board and staff all loved the gentle fun it poked at the folklore and occasional foolishness that have grown up around the story of the three Nephites. Well, it gravely offended a few readers, who felt it was nothing short of blasphemy.

Lavina: What has been your greatest frustration during these last five years?

Jack: Incessant rumors and speculation about the Church, its leaders, its programs, and its people. Editing DIALOGUE means you are constantly hearing stories, sometimes from anonymous sources, tipping you off about one thing or another. Most of these rumors concern fatuous trivia, some of them are mean spirited or even ridiculous. We’ll be glad to put some distance between us and this sort of thing. On the other hand, we’ll miss what came to be the cere monial conclusion to our regular staff meetings—Allen Roberts’s gripping accounts of the unfolding Mark Hofmann investigation.

Lavina: Have you experienced unexpected rewards?

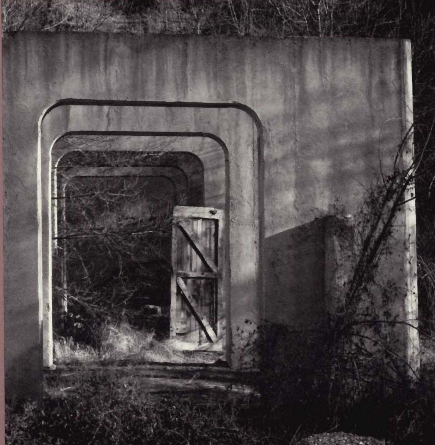

Linda: One of the most pleasing has been the flowering of serious art on our covers and in our pages. This has been a particular interest of mine since I was an art major at Utah State University. Having DIALOGUE in Salt Lake City has enabled us, with the expert help of our art director, Frank McEntire, to build ties with many painters, potters, photographers, and sculptors who have allowed us to feature their creations. Another satisfaction has been the occasional burst of high humor in the fiction we have published. We all need more of this in our lives. Even so, the greatest reward has been the opportunity to work day in and day out with gifted writers and committed people of all kinds. We began with the haunting nightmare that we would always be short of good manuscripts and dependable volunteers. We soon found these to be the least of our worries.

Lavina: As you leave, do you have any lingering wishes or unfulfilled dreams for DIALOGUE?

Jack: Those are probably implicit in what we have already said. DIALOGUE’S writers have much to say to us all. We find their work insightful, inspiring, and stimulating. We wish the journal were read and discussed much more widely than it is.

Linda: Any way you look at it, DIALOGUE has made quite a mark in its first twenty years. Who knows what the next twenty will bring? We are confident that Kay and Ross Peterson will take the journal its next lap with style and courage. We wish them luck!

Lavina: Leaving DIALOGUE may be quite an adjustment for the two of you. What is next?

Linda: It will be an adjustment because we’ve loved this experience. But five years is long enough. I’m going to take a month off to relax, get my files organized, and set up my computer and writing hide-away at home. I’ve just about completed the research for my next book. It is the story of Muriel Hoopes Tu, an American Quaker woman who went to China in 1920 and lived there for sixty-seven years. She died last spring. I’ll also continue as editor for the new Mormon Studies series of the University of Utah Press.

Jack: One thing leads to the next. I’ll be continuing my professional career at the University of Utah, and I’m the new editor of the Review of Higher Education, the journal of my professional association. A colleague said to me the other day: “You are stepping down from the Dialogue editorship to take a bigger one.” That’s ridiculous. No professional journal publishes anything like the range of material that Dialogue does—scholarship, poetry, art, fiction—nor do they deal with issues and ideas that touch the very center of their readers’ personal lives. Nor must their editors raise their entire budgets. No, Dialogue is a professional journal—and much, much more!

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue