Articles/Essays – Volume 19, No. 2

Service Under Stress: Two Years as a Relief Society President

3 September 1984

Today my youngest child went to school all day for the first time. Every mother approaches this milestone with both anticipation and dread. I reached this point once before, six years ago, before the adoption of our third baby swept me suddenly back to square one. If it was a setback, it was the happiest one imaginable. Now, however, poised between treatment for a serious illness and hope for a plunge into a new phase of life, I would like to use the gift of uninterrupted time, a scarce commodity for fourteen years, for some written reflections.

I spent two of those years as Relief Society president in our ward in the Washington, D.C. Stake, from June 1976 to July 1978. I had never con templated having this experience, certainly not while in my thirties with such small children. We had lived in the ward only nine months, and I had never served in a Relief Society presidency. I had never been president of anything except a group of college girls who wore purple dresses on Wednesdays. As an adult, I had never really lived in a typical ward, having gone from student wards to seven years in the mission fields of Asia. I did not fit my own image of a Relief Society president at all. My first thought was, “But I don’t even bake bread!”

I was taken by surprise. I didn’t know what to expect. Two years later, I was still surprised.

***

Every ward is unique; consequently the challenges of one Relief Society president are different from those of another. Several factors made our ward different; each has challenged me and other ward leaders, including my husband, who now serves as bishop of the same ward.

Any large city attracts people from their original homes and extended families—many for professional or educational reasons, some because they are trying to “find themselves” in a new and more varied environment, and still others because they want simply to escape. Church members are scattered over a large area. Washington also attracts many visitors—tourists, people dealing with the federal government, patients in the city’s three large government and military hospitals, all located within our ward boundaries.

Such a location causes a great deal of coming and going and constantly shifting ward membership. Reorganization is endless, and it is often difficult just to know who is here, not to mention making ward members feel welcome and meeting their personal needs. Loneliness is a problem for some, especially those who are living alone or who have recently left home. In spite of our efforts to provide activities and opportunities for Church members to meet socially, some still feel isolated and alone. Members in large cities are more likely to turn to the Church for help in times of illness or trouble than to dis tant families and neighbors. Transportation needs to be provided for women who do not drive and are either incapacitated or lack confidence to use public transportation. Hospital patients, even though not members of our ward, need visitors and concerned friends, and their families often need transportation, housing, and encouragement. Other visitors sometimes call upon local Church members for housing, transportation, sight-seeing guidance, babysitting, and other services.

Young, single people entering the city without definite goals or attempting to escape from problems often find themselves emotionally lost and discover that their problems have somehow moved with them. They change apartments often, have frequent crises in their personal relationships, get into financial straits, and sometimes become physically and mentally ill. They tend to seek out father and mother substitutes among the older members of the ward and request frequent counseling and practical help.

Since the years of my tenure, our stake has created both a singles ward and a Spanish-speaking branch, drawing those members away from our ward into specialized congregations. I have mixed feelings about this. While administratively sensible, such moves deprive members of the diversity of acquaintance which the Church can offer in an urban area. I remember the young single women who were then part of our ward as a source of both some of the sweetest friendships and some of the most painful problems I had as Relief Society president.

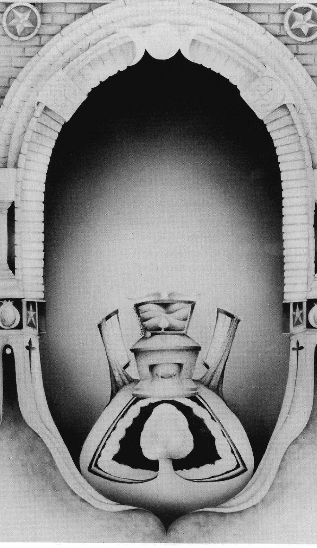

A rarer distinction of our ward is the location within its boundaries of a temple, until recently the only one east of the Mississippi. The Washington Temple has been maligned architecturally by some (and perhaps there is a certain resemblance to a Disneyland castle); but for the people who live and work in its shadow and watch the seasons and the various lights of day and night set off its whiteness on a wooded Maryland hillside, it is a source of in spiration. Speakers in our ward often refer to the temple as a blessing, and they are right. Ward leaders know that it is also a source of challenges.

Besides attracting many visitors and generating a good deal of missionary work, the temple needs temple workers. During my years of Relief Society service, the ward experienced a tremendous growth in membership as the Church purchased or rented large numbers of apartments within our boundaries to house these men and women. When I first became Relief Society president, there were three visiting teachers for all of the temple workers living in our ward. By the time of my release two years later, there were thirty. This time preceded the consolidated Sunday meeting schedule, and extra sessions of Relief Society were held on Sundays for the growing number of women who could not attend on a weekday morning. Because of their employment, most of the temple workers, of course, attended Sunday morning Relief Society. When I began, our Sunday session was so small that we had been meeting jointly with another ward. Two years later, meeting alone, our Sunday group included almost a hundred women and overflowed into the hall.

These were distinctive women. As I faced them on Sunday morning, I would try not to think about how many former ward and stake Relief Society presidents, stake and general board members were looking back at me. Most were older than my mother; but without exception I felt only love, support, and cooperation from them, never criticism or condescension. Many of them taught me what beauty is at seventy—the reflection of a lifetime, still continuing, of worthwhile service and activity.

Most of the temple workers lived near one another, and they watched over each other in a self-sufficient community. They presented few extra problems for me. Still, their age alone predicted that some would become ill, and some would be hospitalized. During my two years, twenty-one women in our ward were hospitalized for reasons other than childbirth, and five from other places were hospitalized here for substantial periods of time. Nine other women had husbands or children in the hospital. Hospital visiting was difficult for me because visiting hours were always in the afternoon and early evening when my children, who were not permitted in the hospitals, were at home and my husband was not. Still, I wanted to visit these women personally, I sensed that most of them wanted or expected a visit, and I usually managed. Some of my most rewarding experiences were with seriously ill women.

The temple workers also shared the feeling of being uprooted, of missing friends and familiar people left behind, of living among people who did not know or appreciate their talents and experiences. They had practical difficulties getting around and attending to daily needs in a large new city. As their numbers grew, I sometimes had the feeling that they forgot the ward had other members with needs and problems calling for the attention of the leaders, or they supposed that they alone were outsiders in a ward which in fact included very few long-time residents. All ward leaders were constantly searching for ways to help new members feel welcome and appreciated. But it seemed imposible to satisfy everyone. I soon realized that I did not have the time to pay personal visits to all the sisters who came to work in the temple. Those I knew best were ones with serious illnesses or other special problems and those whom I asked to help me as visiting teachers or in other ways.

A few of the temple workers made a real effort to be involved with the activities and the families of our ward, and some became beloved surrogate grandparents to children whose own extended families were far away. These, however, were in the minority. Most of the temple workers channeled their time and energy into their demanding temple work. Yet the time came when they virtually filled our chapel, and families, arriving with children in tow, had trouble finding seats. Soon after my term as Relief Society president ended, our stake presidency created a ward for temple workers, regardless of their place of residence.

A few of the temple workers were young and single women, and I soon learned that this could also signal trouble. The temple is a lovely place, an ideal to many young Mormons—but most of them do not want to spend all their time there. I found that at least some of these very young employees were there, perhaps unconsciously, because they had failed to cope with the outside world. They were sweet girls, but without a firm sense of direction. They were waiting to marry, hoping (sometimes on the basis of promises in blessings) that working in the temple would be a means to that end. In the meantime, they were extremely insecure and susceptible to suggestions from anyone they considered to have spiritual authority—the bishop, a fellow temple worker, a counselor at Church Social Services, a boyfriend holding the priesthood—or, to my surprise—me. In some cases, these girls had deep emotional troubles. Becoming involved in their personal problems was both the most interesting and the most emotionally draining part of my work. I was startled to realize that some of them regarded me as a sort of female bishop who should be in spired to tell them how to solve their problems. I became close to several and wanted very much to help them. It was hard to admit to myself and to them that I could listen, sympathize, and perhaps help them to see things in a different perspective, but I could not make their decisions or live their lives for them. Good counsel from a local LDS psychiatrist helped me, but even experience did not make the situations easier.

***

Aside from these special problems, my two years were full of things familiar to any Relief Society president anywhere, though unexpected or only dimly foreseen when I began.

I shopped for and delivered groceries to needy families, itemized each purchase, and submitted the bills to the ward clerk. I became the object of good natured ribbing for coming in for my monthly paycheck. I learned that Relief Society nurseries are notorious sources of potential friction, and I studied diplomacy helping my education counselor pacify mothers who wanted their babies’ diapers changed and mothers who did not, mothers whose children were allergic to the morning’s snack, mothers who wanted their children to have milk or juice during the morning and nursery volunteers who had to clean up the milk or juice, volunteers who were angry with the Primary for getting into the Relief Society toy box, mothers and volunteers who disagreed about how to handle a child who hit, bit, or cried continually, women who did not want to help in the nursery, and mothers who were willing to take their turn but were not happy about the way things were done.

I solicited contributions to the Nauvoo Women’s Monument fund but avoided telling my sisters how they should feel about the Equal Rights Amendment. (Subsequent use of LDS women for political purposes in neighboring Virginia made me extremely grateful that the ERA had won early approval from the Maryland legislature.) I called and interviewed visiting teachers, which was time-consuming but the very best means of getting to know the women. I worked with the bishop to keep Relief Society staff positions filled, oriented new board members, and tried to encourage these women when I was fully sharing their insecurities.

I reported our doings to the editor of the ward newspaper and arranged for displays in the trophy case. I attended meetings, organized meetings, presided over meetings, and held meetings to plan meetings. I dealt with last minute crises before meetings, crises which often began with a phone call at 8:00 on a Tuesday morning. Our Relief Society produced four major ward socials during the two years and three others for women only; we catered food for six wedding receptions.

I visited sick women, new mothers, newcomers, families with financial and personal problems, and people whose help I needed. I visited homes, hospitals, and a nursing home where one of our members lived. I rented and delivered three wheelchairs and one commode. I stood helplessly by as a rescue squad arrived at the apartment of a woman who had suffered a stroke, and my hus band made what was for him the ultimate sacrifice by allowing the children and me to care for her little white dog for three days. I received calls for advice on husbands who had not come home when expected and babies with severe diaper rash.

I recruited volunteers for a great variety of activities—temple assignments, compassionate service, food and help for socials, dinners for visiting Church dignitaries, and ward fund-raising projects, including experimental studies at the National Institutes of Health for which Church members often volunteered as subjects. I became an exchange and referral center for housing, used furniture and clothing, employment, telephone information, transportation, baby sitting, house sitting, and care of the elderly. I wrote well-deserved thank-you notes to the many people who helped me, and ordered and distributed Relief Society manuals in Spanish and English. One cold December night, I delivered six large turkeys to the six women who would be roasting them for the ward Christmas dinner.

Several times our home became headquarters for newcomers, the temporarily homeless, and passers-through. These ranged from a woman whose husband had been seriously injured in an automobile accident in Germany and sent to Walter Reed hospital to a poor little soul who claimed to have been left stranded at a Washington airport by a boyfriend who had promised to marry her. (The first woman rented an apartment and stayed to become an active member of our ward during her husband’s long recuperation. The second, after regaling me with more and more fantastic stories of her life and making many long-distance telephone calls from our kitchen, finally boarded a bus for California. Her story turned out to be a fabrication, and our last news of her was a postcard from somewhere in Oklahoma.)

I met and talked with counselors at LDS Social Services about our mutual efforts to help women with serious emotional problems. I kept an ear open to the needs of some twenty new mothers during one year and helped when two ward members died. I sang in the stake Relief Society chorus and organized Christmas carolers and small singing groups for socials. I attended baptisms of new converts and tried to ease them into a new way of life and a new circle of friends. I coordinated schedules with the Relief Society of the ward which shared our building.

I made announcements concerning coming events, bulk food orders, craft fairs, classes, tickets, lost and found items. I helped two new Relief Society secretaries struggling to take attendance discreetly in sacrament meeting, where there were always new and unfamiliar faces, and in four separate weekly sessions of Relief Society—Tuesday morning, Sunday morning, Young Adults, and Spanish speakers.

***

This catalogue is extremely full of “Fs,” and that is not as it should be. I have tried to show the great variety of things with which a Relief Society president may become involved, but I do not mean to suggest that I did all these things single-handedly. I used to sit in the chapel during sacrament meeting, looking from one woman to the next, realizing that I felt a great gratitude to almost every one for help willingly given. I am not an administrator by inclination; I would rather do twice as much work myself than ask someone else for help. This calling was good for me because I could not possibly do everything myself. I found that most people were very willing to help; but it was still painful to ask, and the most beautiful words in the world became, “I’d be glad to.” It is a tribute to the women of our ward that I heard those words far more often than “I’m afraid I can’t.”

I had devoted counselors whom I came to love, even though we did not start out as a naturally compatible group. Their interests and abilities lay in areas such as homemaking activities where my own were weak. We had excellent teachers, an experienced and beloved secretary, a dedicated visiting teacher supervisor, and many women who gave time, talent, and service.

I offer this long list only to understand better why this calling so dominated my life for two years. At times when I felt overwhelmed, I was advised to dele gate responsibility. I tried, but I learned that delegation both reduced my load and added something back to it. Each time I asked someone to help, it also became my duty to follow through—to explain responsibilities, show interest, and lend necessary support.

***

If anyone asked me, “What were the hardest things about your job?”, I would answer without hesitation, “The telephone and Sundays.” Perhaps this is because these two aspects most affected my family, and I worried and felt guilty over having to divide my time and attention among so many people in addition to them.

When I was called to my position, the bishop assured me that I was to put my family first. I tried hard to do this, but I found it more easily said than done. My husband was very supportive and soon realized, if he had not before, that I had a full-time job. Busy with a demanding profession of his own, he helped me in many ways, washing more dishes in those two years than in all the thirty-six that preceded them. I felt the children could not be expected to be so understanding or flexible. Perhaps at first I overcompensated by involving them too often in my activities. I was deeply hurt by one or two remarks indicating that women in our ward were not accustomed to a Relief Society president with small children in tow. (My predecessor had had grown and teenaged children and had served for six years.) I was bewildered by this seeming intolerance from other women; after all, motherhood was supposed to be our most important calling. But this problem soon faded, perhaps be cause I had been overly sensitive and the problem had been more perceived than real.

The children shared some valuable experiences with me. My daughter’s love of little children and natural sympathy for afflicted people made her a good companion for home visits to new mothers, elderly women, and injured people. Both children still remember the three of us guiding my son’s young Primary teacher to a doctor’s office after she had temporarily blinded herself with a sunlamp. They also remember a Christmas Eve visit to a little cancer patient in Walter Reed Hospital who had lost his hair but who later came to church in a bushy brown wig and went home to Colorado with good prospects for recovery.

Actually, my children’s attitude was very good. Usually I was able to give them the time and attention they needed because I was determined to do it, and I felt that there were compensations in the awareness my work gave them. I was glad to have them know that people beyond our family circle needed our help and our concern. Sometimes they could be involved directly in extending that help. Nevertheless, my little boy spent a good deal of time playing alone while I responded to phone calls. I sympathized fully when their response to my release was, “Yay! Now you won’t have to be on the telephone so much!”

I had never spent much time on the telephone, and we had lived quite happily for five years in the Philippines without one. Now, although I seldom got a bishop’s middle-of-the-night calls, I found that the box on the kitchen wall could be a tyrant. Calls often began before 8:00 in the morning and continued until 11:00 at night, many the inevitable fruit of delegated responsibility. I remember only one day in the two years when there were no Relief Society-related phone calls. Perhaps something was wrong with our phone that day.

In addition to in-coming calls, I always had a substantial list of calls to make, and many had to be put off until evening because so many women were at the temple or otherwise away from home. My husband arrived home from work at seven at the earliest. The time after dinner, although it was often interrupted by the telephone, was important time with the children. I would often return to the kitchen after 9:30 at night to face the dinner dishes and more phone calls before hoping to snatch a weary hour with my husband and something to read before going to bed.

Sometimes I was philosophical about the telephone, but at other times I became really paranoid. I soon found that to preserve my own balance and my family life, I had to adopt a principle I later heard articulated in a play: “A telephone doesn’t have a constitutional right to be answered.” Sometimes personal and family needs took precedence and I simply let it ring. So far as I know, there were never any dire consequences. My children wondered if that was quite honest, but I preferred that to their concluding that whoever was calling was more important to me than they were.

The best calls were like the ones from my Guatemalan education counselor in Sunday Relief Society: “Here is our need or problem. Here is what I plan to do about it. Is it all right with you?” The worst began, “I’m sorry to call you on Monday night, but —” or, “I just thought you ought to know that—” or, “I think that somebody ought to—.”

It was also hard to know how to handle the calls from a few lonely women who just wanted to talk. I knew their need was as real and valid as sickness or financial trouble. Yet I had only three hours a day when both my children were in school, and I always had more to do in those hours than was possible. When one of these women called, I had to either settle down for twenty or thirty minutes of listening or call back in the afternoon at the expense of time with the children.

And Sundays! I have heard many busy Church members concede that Sunday is a day of rest for them only in the sense that they exchange their weekday labors for ecclesiastical ones. For me, Sundays of those two years were characterized by an intensification of the same kind of labor which dominated the other six days of the week.

I began a typical Sunday by joining in the last half hour of the Priesthood Executive Committee meeting to discuss welfare matters and share other needs of women with the bishopric or priesthood quorums. This essential meeting began early in the morning. I am a night person, but I would not have minded getting up early and going to church by myself. Unfortunately, the whole family needed to be up, dressed, fed, and at the church by that hour. The second year, the early meeting began at 7:30, and I had to arouse the children in the winter dark an hour earlier than on school days. My husband’s priest hood meeting began at 8:00 and we have one car, so leaving the children with him would have been no solution. Friends offered to care for the children until Sunday School, but the early rising would still be necessary, and they preferred to come with us. They were six and four years old when I began, and I felt both guilt and concern about their behavior during the two hours at church every Sunday morning before there was any activity meant for them.

Sunday session and Young Adult Relief Society met from 8:00 to 9:00, and I always attended one of them, even though I had excellent counselors to conduct and plan those sessions. If I had not been there, I would have had little acquaintance with over half the women in the ward. Usually we had no nursery during Sunday Relief Society because I was the only woman there with young children. My daughter was too old for a toys-and-baby-sitter nursery anyway, so she was left mainly to her own devices during Relief Society. Our son, who is less restless and better able to entertain himself quietly, preferred an additional adult meeting with us to a babysitter, so he became probably the youngest high priest in the history of the Church, sitting under the piano in the chapel while his daddy played the hymns. Both children also did some wandering in and out of Relief Society meetings, and most people were kind enough not to be too judgmental about a certain amount of running and paper airplanes in unoccupied areas of the building.

Sunday Relief Society was followed immediately by Sunday School, then by testimony meeting if it was Fast Sunday. If not, we went home for lunch, then returned for Sacrament meeting. Before, after, and often during each of these meetings, I was besieged by people needing to talk. A Relief Society president does not have an office, so these conversations took place in crowded foyers and hallways, in little nooks not occupied by classes, in the Relief Society room or the chapel after meetings, often with the children pulling at me for attention. We were always among the last to leave the building.

I always went to church armed with the latest in a series of little notebooks in which I tried to list things I needed to do. Three categories were outlined for a Sunday: “Bishop” (things to be taken up with him or with the Priest hood Executive Committee) ; “Announcements” (to be made in Relief Society); and “See and Do” (people I needed and hoped to contact sometime during the day). I was seldom able to complete the list. On one Sunday in September of the first year, for example, I had scheduled myself to talk to the bishop about a sister who had had a heart attack and was in the hospital; one whose son in Utah hoped we could bring her back into Church activity; one who had injured herself at work, needed surgery, and was without income while she could not work; one who had just had her eighth baby; and one who was elderly and quite eccentric but had needleworked a nice-looking picture of the temple which she wanted to display in the meetinghouse. I also needed to ask the priesthood quorums for help in setting up tables for our approaching fall social and to remind the bishop that I had not yet been released from teaching a Sunday School class. There were announcements to make in Relief Society about the woman in the hospital, the social, and the seating of families with small children in the chapel so they could leave quietly when expedient. I was to have a visiting teaching meeting with one sister whose family situation made a home visit difficult. I needed to let the church custodian know what equipment to set up for the social. In addition, there were eleven people on the “See and Do” list—women whom I wanted to meet and welcome to the ward, or to whom I needed to speak about visiting teaching assignments, the coming social, Relief Society lessons they would be teaching, the nursery, and personal problems.

Just as I always brought a list with me on Sunday, I always took one home. It would include things I had not been able to do that day, as well as other matters for the coming week. Following this same Sunday, for instance, I needed to talk to the ward executive secretary about a system for keeping track of new temple workers; to ask my education counselor to find out which of our teachers had not taken the Teacher Development Course; to meet and help arrange for the fellowshipping of two young families, recent move-ins not yet involved; to arrange some help for a young woman, recently baptized, who worked on Sundays and had no family in the area; to try to make contact with a divorcee who had once been active but who no longer welcomed home teachers; and to contact a nineteen-year-old single girl baptized two weeks earlier and pregnant with her second child.

I almost always went home on Sunday evening exhausted and overwhelmed. It was difficult to absorb the spirit of a meeting instead of looking for the people I must see afterwards and planning my attack. Our Sunday dinners became what could be set on the table in the shortest time possible. (I tried to have a special dinner on another night of the week instead.) I learned to force myself not to think about Relief Society business on Sunday night unless it was urgent. On Monday morning, I could make my new list, set priorities for the week ahead, and call for help. Things would look more manageable then.

At times the job was manageable, although I had to learn, with my bishop’s good advice, that I could not possibly do all that I might like. The second year, in general, was easier than the first, as I gained confidence, experience, and knowledge of whom to call upon for help. But there was never a let-up for long, and several times I felt that something in me would give under the strain. My husband, who is used to seeing me take on too much, let me cry and rage, and then encouraged me to buck up and finish the job. I did, but in looking back through my little notebooks, I can easily understand why the pressure sometimes exceeded my tolerance point.

There is something about December. The Christmas season brings both a surge of social activity and increased depression and anxiety for people with problems. During both Decembers of my term as president, I was sure that nothing would happen at our house on Christmas morning because I was too busy with other demands. My children were beginning to be skeptical about Santa Claus, but my faith in him was confirmed when, somehow, Christmas tree, stockings, and presents did materialize after all.

The first December we had just completed organizing and staffing our Relief Society; we held a luncheon and meeting for the thirty-five officers and teachers, a fall dinner social for the ward, and a wedding reception for a young Korean girl whose Asian concept of the proper amount of food for her wedding guests far exceeded her family’s resources. Now we were engaged in organizing an elaborate turkey dinner for the ward Christmas social. I was deeply in volved with a lonely elderly woman who was struggling with depression while recuperating from a heart attack; with the pregnant nineteen-year-old, and with a woman for whom I had arranged housing with a lovely Guatemalan family in the ward and who now appeared seriously mentally disturbed. The mother of the Korean bride was ill, and her daughter-in-law, who lived with her, was about to have a baby and needed baby clothes and a bed. A woman who had been injured at work needed transportation to church, and her faithful visiting teacher was away. The food chairman for the Christmas dinner had left town to attend the birth of a grandchild. Christmas gifts needed to be delivered to needy and elderly members of the ward. My telephone never seemed to stop ringing. A Relief Society group was going Christmas caroling, and I had agreed to play a piano duet with my husband at a Christmas pro gram and to accompany a friend who would be singing in church on Christ mas Day. I was also to give a talk in ward conference in January.

At this point, my family—parents, sister and brother, and their spouses and children—arrived for a long anticipated visit. My family’s feelings toward the Church range from enthusiasm through ambivalence to antipathy, and I was trying hard to relax and not let the hubbub around me be too obvious. On the first day of their visit, I took a little niece and nephew to Relief Society along with my son while their parents went sightseeing. That evening, just as we were sitting down after dinner to make plans to visit a museum the next day, the telephone rang again. A young mother of five had hit her head while ice skating and was going to have to stay in bed for an unknown length of time. The next day I was telephoning from the museum, trying to find people to do the injured mother’s laundry and care for her children. I visited her in the afternoon, found she had no help for the evening, and prepared supper for her family before returning home at 5:30 to start my own dinner for twelve. I would rather forget that evening. Though everything I was involved with was either good or unavoidable, it was obviously too much all at once.

***

Several impressions and concerns stand out from my experience of those two years.

I am a reasonably social person, and I enjoy and appreciate my friends; but I also need and enjoy a considerable amount of solitude. One of the greatest values of my Relief Society job was that I developed relationships with many fine people whom I would otherwise have known only slightly. But I often thought of a story about Senator Edward Kennedy who, surrounded by a crush of people at a political rally, would sometimes mutter to an aide, “T.M.B.S.!”— too many blue suits. It was his signal that he needed to escape and be alone for a while. I knew that feeling very well. I was determined to do all I could for the women in the ward and not to let my family suffer. Most of the time I think I succeeded, but I paid a price. Being overly organized and self-controlled put a real strain on me, and I had to sacrifice almost all of my time to write, read, or pursue other solitary interests. Most of my little notebooks have poems in them, scribbled among all the Relief Society notes at odd moments. I often stayed up too late reading because I felt starved without it. It was difficult to satisfy the needs of people who were lonely or had too little to do when I myself felt almost desperate at times for less activity, less social contact, more time to myself.

I did learn, as time went on, that everyone would benefit if I were occasionally a little more selfish with my time. My visiting teacher, a good friend and neighbor, gave me a valuable gift by driving my children to Primary each week. Sometimes there were pressing matters which could best be handled while the children were away, and sometimes I simply took the phone off the hook and went to bed for a while. But I was able to write a story or two and catch my breath occasionally before plunging in again.

In the last of the little notebooks, I have copied a quotation from Anne Morrow Lindbergh: “When I see an island, I think of our constant urge back to nature. You can have an island on land, too. Each man has his island, a quiet place away from the hubbub. To some it is the Isle of Happiness, a practically inaccessible vision. This is a repeated theme in literature and reality.”

I was able to sacrifice my time more willingly at some times than others. I am not inspired by grocery shopping, but during a six-month period when I was doing it regularly for another family as well as my own, I found I did not resent it. I was very fond of the young mother of the other family, sympathetic to her situation, and aware that she had had to set aside a good deal of pride to accept this needed help. It was important to me to help her feel comfortable by minimizing any inconvenience to me. Her attitude made it a genuine pleasure to help her. On the other hand, I grew tense and resentful when I had to spend large amounts of time and energy planning social activities or arbitrating petty quarrels at the expense of more important things.

I discovered reserves and sources of strength upon which I could call. Our family was healthy throughout two winters of record cold. The children were ill only once, with chicken pox, and I did not expect the Lord to spare us that after we had just housed a family of infected little cousins. In looking back, a sort of “loaves and fishes” miracle must have occurred in my behalf, giving me more time than there was in a day and more capacity than normal to do things.

But my weaknesses also became more obvious. I was disappointed when I was not able to speak with necessary frankness for fear of being thought unkind or unhelpful, when I overreacted to criticism, when I showed my weariness and impatience at the end of a busy day to the children or to someone who had innocently made the phone ring once too often, when I let myself get too busy to exercise and pray thoughtfully, and when I reacted to a new problem in the ward with tension and dread as well as sympathy. I was relieved to hear, our bishop, released just after I was following seven years of service, say that he now found it good to hear of problems with concern but without feeling direct, personal responsibility.

Working closely with priesthood leaders and learning about the operation of a ward was an education by itself. To see a group of men who are also fathers and full-time breadwinners willingly assume responsibility for the temporal, social, and spiritual welfare of some 500 people is remarkable, and not to be found, so far as I know, outside the LDS Church. I began to understand the responsibilities which a bishop and his counselors carry and gained an enduring respect for the men who take them on. Working with the leaders of our ward was almost entirely a positive experience. I had known our bishop for many years as a former Congressman from Utah, a friend, and erstwhile political opponent (successful) of my father. He took a fatherly interest in me and was extremely kind and encouraging. Several times the thought of the large load he had been carrying for six years prevented me from adding to it by telling him I wasn’t sure I could continue.

Only occasionally did I feel disadvantaged operating in the priesthood dominated councils of the ward or sense a bit of kindly condescension, but I did become more keenly aware of the limited role women play in Church policy making. Except for the hour-long monthly ward correlation meetings, which all auxiliary presidents attended, I was the only woman present at the ward executive meetings, and I was invited to those only to discuss welfare matters. At the time, this was an interesting new experience, but in retrospect I wonder why over 50 percent of the Church membership should be so underrepresented. I saw situations where needs could have been better met if more women had been actively involved in planning and decision-making. I also felt sometimes that a woman’s (and a man’s) own desires and interests should be considered before ward callings were made, and that the secrecy surround ing those callings and releases was probably unnecessary. I did not become a crusader for the priesthood for women. I had more than enough to do already. But I came to feel that women could and should participate more directly and in greater numbers in making plans and decisions which have such a great effect upon their lives and their families.

I regret I was not able to find time for closer involvement with inactive ward members. I understand now, as I did then, that my own ambivalence toward inactivity as well as lack of time contributed to this situation. Several members of my immediate family are estranged from the Church. Some of them receive home teachers, attend church occasionally, and have a cordial relationship with Church leaders. Others want to be left entirely alone. These are people I love and, I think, understand. I do not share their feelings, but I respect them and know that preaching and prodding would be the very least helpful and effective thing I could do. On the other hand, I have heard many inspiring stories and expressions of gratitude for the home or visiting teacher whose persistent interest and friendliness has led an inactive member back to a way of life which he or she is grateful to have found again. I did have, and maintain, a good relationship with one inactive member as her visiting teacher. I made some cautious contacts with some of the women in our ward who had declined in the past to have visiting teachers or any involvement with the Church, but to say that I was not aggressive would be an understatement.

It was also difficult to make time for neighbors, friends outside the Church, and even friends in other wards, though we had many house guests and managed some social life of our own. I’m sure I was not the first to notice a certain incompatibility between the Church’s growing emphasis on “friendship ping” and missionary work and the burgeoning number of meetings and activities which consume our time.

It was easy to explain to other Mormons what I was doing with my time. The words “Relief Society president” communicated immediately and quite accurately. But to most non-Mormon friends and acquaintances, the job meant nothing at all. Many of my neighbors are working mothers whose children are in school. My husband works in an office of professional people, most of whom also have professional spouses. As I met these people and was asked inevitably, “Do you work?”, there was always a deep breath and a pause on my part. I could not bear to say “no,” as I had never worked harder in my life. I could say, “I stay at home with my children,” but that would hardly have given an accurate picture. Also, many times my friends knew that my children were in school part of the day, and that I had a graduate degree and had been a teacher. What was I doing now? Usually I would explain that I was heavily engaged in volunteer church work, and leave it at that. If there was opportunity for more than a brief conversation and the other person seemed interested, I would try to explain what I was really doing. Most people expressed only polite interest, but one woman, the youngest in a Catholic family of fifteen, endeared herself by exclaiming, “I think that’s marvelous. I understand exactly how it must be. It sounds just like my family!”

One friend of my husband’s, upon hearing from him a rather realistic account of my current activities, asked, “Why does she do it?” That made me think. Why was I doing it? Because I had been called by the Lord to do it? Did I really believe that? Because my bishop, my husband, or my Church community expected me to do it? Because it was an honor to be thought capable, and I expected it of myself?

All of these were factors. But what really made it worthwhile?

When the bishop first called me to this position, I felt physically shocked—cold-shower shocked. After I began to collect my thoughts again, I felt I did not know what the job would involve and I certainly was not very experienced, but I knew I would enjoy working with other women. That intuition proved correct. The women themselves were the main reason why I did it and why I am glad now that I did. My intense involvement with many women made me aware of many aspects of their lives and personalities—not only their problems, but their hopes, fears, sacrifices, strengths and weaknesses, and the many kind things they did, unasked and unsung, for each other.

There are many with whom I shared significant experiences. Two young mothers from Latin America struggled, with their husbands, to hold their families together through persistent unemployment; three young women suffered from mental illnesses serious enough to require hospitalization; a convert kept her faith strong in spite of serious family problems, financial struggles, and the weaknesses of Church members she had admired. A mother of three small children willingly shared her time and concern for others in spite of her family’s constant financial insecurity; a mother discovered that her second little son was suffering from the same degenerative disease which had taken the life of her first child, and might also affect her third little son and the baby she was carrying; a single lady with no children of her own took an intense interest in all the children of the ward and gave invaluable help to our nursery and to young mothers with many children and busy husbands.

I knew several women who, with much love, tact, and personal sacrifice maintained a delicate balance between their own Church service and the needs and wishes of nonmember husbands. A young wife helped her husband find his way from excommunication at his own request back to Church activity, a temple marriage, and an application to adopt a long-awaited baby. I will always admire our former Relief Society president, still a very busy lady, who began visiting a long-inactive woman who had struggled with alcoholism and loneliness, became her friend, and brought her often to church. A beautiful woman in her sixties, the survivor of an automobile accident which had taken the life of her husband and half-blinded her, deeply moved all of us with her Relief Society lessons. Several women faithfully visited and carried on one-way conversations with a mother of three who lay unresponsive for several months in a hospital bed after surgery for a brain tumor and finally spoke to her husband on Christmas Eve. A lovely temple worker wrote music and poetry, loved children and had none, and underwent surgery for cancer with grace and strength. A white-haired Englishwoman’s beautiful speaking voice added poetry to many of our lessons. Good-natured young women struggled valiantly with overweight, financial problems, conflicts with roommates, and the elusive ness of marriage. A young woman taught and loved my son, worked hard to keep our Young Adult programs afloat, and later faced the realization that her husband’s conversion to the Church had been less genuine than her own.

Widowed and divorced women raised teenaged children alone and experienced heartaches that the presence of a caring father might have prevented. An elderly Swedish lady often went to church and concerts with us and engaged in running conversations with unseen people, but loved music, plays, and dances, had made a violin, and succeeded in going to the temple as well as on a Young Adult overnight ca.mp-out. A recent convert recruited Relief Society refreshments for a reception following her third marriage. The reception, as it turned out, was held in a room behind the bar at a local VFW hall, and the liquid refreshment had obviously not been furnished by the Relief Society, but the new husband later joined the Church. There was a young woman who fought for her life in Bethesda Naval Hospital after having been attacked and repeatedly run over with a car outside a military base in Cuba; a Guatemalan mother, a recent immigrant with a temporary visa, who was raising a superb family of young adults and teenagers in a small apartment; and the wealthy and prominent couple who lovingly accepted this woman’s daughter as their daughter-in-law. I will not forget one young convert, a twenty-year-old unmarried mother of a loveable mulatto baby boy. It was from her, appropriately, that I first heard the news that the priesthood was to be extended to black members. It was also from her that I learned how very, very hard it is to compensate for years of emotional deprivation.

All of these years became part of my life. Many others earned my deepest appreciation by working closely with me. I miss the close involvement with such people now. All of them were important to me. But two women merit particular attention.

***

In the first of my little notebooks, I wrote after a conversation with the bishop: “Cleeretta Smiley. Let sisters know she will be working toward full integration into ward activities. Contact her.”

Cleeretta Smiley is a striking, vibrant black woman, a former teacher of home economics in a Washington high school who inspired many young black girls to pursue careers in fashion design and became administrator of home economics programs for the District of Columbia public schools. When I met her, Cleeretta had been a member of the Church for about two years and was coming into our ward from the original Washington Ward, which was being dissolved. She was one of the two black members in a ward which now has over thirty. Our bishop was to be her home teacher and was very anxious that the women accept her fully. I met Sister Smiley, was attracted to her enthusiasm for life, and decided to make myself her visiting teacher. So began a per sonal association which I have thoroughly enjoyed and which, fortunately, was not terminated by my release.

My visits with Cleeretta were always uplifting, even though her circumstances were hardly ideal. During those years, she was divorced and experienced the normal problems of raising teenaged children; but her conversations were always full of her current plans and activities, her love for her work and her students, and her appreciation for the new insights continually coming to her through an understanding of the gospel. She was full of missionary enthusiasm and was particularly anxious, as she put it, to “improve the complexion of our congregation.”

A year after I met Cleeretta, our Sunday Relief Society needed a new teacher to give lessons on home management and economy. This was Cleeretta’s bailiwick, the bishop was enthusiastic about the idea, and a recent change in our ward schedule had made it possible for her to attend Relief Society for the first time. She accepted the call with her usual enthusiasm and was an excel lent teacher. Just as delightful to me was the attitude of the other women. Most of our Sunday Relief Society members were older women; many of them were temple workers from the southern states. Yet I never heard or saw one of them show anything but acceptance and support of Cleeretta. During her first lesson or two, the class’s eagerness to help her succeed was almost tangible. I do not believe this would have been entirely the case fifteen years earlier in the more “liberal” ward in a northern city where we were then living.

Things had changed, and I believe that change made possible the announcement of 9 June 1978, which most of us had despaired of ever hearing in our lifetime. I also believe people like Cleeretta Smiley helped make that change possible.

When I heard and had absorbed the news that the priesthood was to be extended to “all worthy male members,” I telephoned Cleeretta. We laughed and cried together. Almost exactly two years after the first note I wrote: “Find out for Cleeretta: Can she wear a blouse and skirt in the temple? Can she make her own clothing?” At the end of July, I went with Cleeretta to the temple, as did several of the temple workers who had been her students that year. She was thoroughly happy. I was happy, too, but not in the excited way I expected. Instead, it seemed the most natural thing in the world for us to be there together, and I could only think as I looked at her, “Now, what was all the fuss about?”

In 1981, three years after my release, Cleeretta Smiley began two years of excellent service as education counselor in our ward Relief Society presidency.

***

The other unforgettable experience began with a phone call informing me that Alice Macaulay had been hospitalized with a heart attack. I had been Relief Society president for only three months, but I knew Sister Macaulay was a widow from New Jersey who had been working at the temple but living across the Potomac River in Virginia until just before her illness. She had moved into an apartment in our ward, but there were no other temple workers near her.

I went to the hospital, met Sister Macaulay, and learned that she lived alone. She and her husband had converted to the Church, and her three sons, who lived in neighboring states, were not members. A few days later, Sister Macaulay called to tell me that she had come home. There was no one there to help her. “I told the doctor I was sure someone could help me,” she said. “I believe the Lord will take care of me.” My throat tightened. The Lord and who else? I thought.

I did not handle Sister Macaulay’s situation very well at first. I was inexperienced and genuinely frightened. Here was a woman who had been seriously ill, whose doctor probably would not have released her without her assurance that someone would be with her. Apparently it was up to me to provide that someone. I talked with the bishop and with several women in our ward who were nurses or physician’s assistants. All offered some help, but no one could provide it full time. I asked Sister Macaulay if any of her family were planning to come. No, she said, they had their jobs, their families.

Her living quarters suggested that she could afford to hire a nurse, but she insisted it was not necessary—just someone to help out a little. For several days, women in the ward who lived near stopped in to help and even spent the night, but all had jobs or families of their own, and this amount of help could not be asked of anyone very long.

As Sister Macaulay’s physical condition stabilized, help began to taper off. Faced with long days and nights of recuperation alone in her apartment, she became depressed and telephoned me and others at all hours asking for some one to be with her, complaining that no one cared about her. Soon two of the women who had been helping agreed to take turns going to Sister Macaulay’s apartment every evening, as long as necessary. One had a full time job, the other was a college student, and they knew they were making a commitment that might continue for weeks or months.

These two went faithfully every evening for about three months, and I visited at least once a week. Sister Macaulay’s regular visiting teacher helped often during the day. Several of us took turns driving her to her doctor’s office. Sister Macaulay was both appreciative and demanding, and I still received occasional irate calls from temple workers not in our ward, whom she had tele phoned during a low period to say that no one cared about her.

Feeling that I had reached the end of my resources one evening, I tele phoned Sister Macaulay’s oldest son in New Jersey. That phone call explained many things. We had all been amazed that her children had shown so little interest in her predicament and had wondered if they had disapproved of her joining the Church and working in the temple. I told Mr. Macaulay about his mother’s depression, what her needs seemed to be, and what our limitations were. His immediate response was, “Then she’ll have to go to a nursing home.” Sister Macaulay was proud and intelligent, and even in her illness it was obvious that she was used to looking attractive, having some luxuries, and being deferred to. I thought she would probably rather die than be placed in a nursing home. I told her son that I did not think her physical limitations were great enough to require that. She just seemed lonely. “Look,” he replied, “I told Granny that if she went down there by herself and got sick, that would be her problem. If she’s making a nuisance of herself, we’ll put her in a nursing home.”

I told him she was not making a nuisance of herself, said good night, and hung up. This woman’s heart was aching with something much harder to bear than coronary pain. We would do the best we could, realizing from now on that it was not really we by whom she felt neglected.

Sister Macaulay slowly improved. She came to our home on Thanksgiving, stayed overnight and helped our daughter read a whole book by herself for the first time. A brother and a niece came from South America and spent some time with her. One son finally drove to Washington and took her home for a short visit. She grew stronger, began to go out, then to drive, and finally resumed part-time work at the temple. She was cordial when she came to church. I sensed, however, that in some way Sister Macaulay had alienated many of the other temple workers. Not many of these usually helpful women had offered help during her illness, and they did not associate much with her now. Perhaps her isolation from the others in more expensive quarters indicated a tendency to withhold herself from others and gave an impression of condescension. I wondered if similar problems affected her family relationships.

After a year of less contact, Sister Macaulay’s home teacher called to tell me that she was in the hospital again. Mentally I began gearing up for problems, but this time was different. She returned home quickly and insisted that she could manage without help. One of the women who had helped her so much before began visiting again and kept me informed.

One night she reported that Sister Macaulay seemed very ill—she had not even put in her dentures for the home teacher’s visit. I smiled but agreed that this was significant. The next morning I telephoned and she asked if I would go with her to the hospital. I left right away but saw an ambulance leaving her apartment house just as I drove up. I followed, and after some time in the hospital emergency waiting room, was allowed to see her. She was attached to many tubes and looked very ill, but she knew me.

“This is the third time,” she whispered. “I guess it’s the last.”

“That’s only if you’re drowning,” I teased.

Four of us were allowed to visit her in the hospital’s progressive care unit—the faithful friend and neighbor, the home teacher and his wife, and I. For about two weeks we visited her often, and she always recognized us and scolded us if we had missed a visit. One weekend, her three sons came. We were told later that she had released at them all the bitterness their neglect had built inside her. Her mind seemed clear about everything else, but she would not acknowledge that they had ever been there. The night they left, she had another heart attack. For the first time, I acknowledged that Sister Macaulay might not get better.

On a June morning a few days later, I sat by her bed and held her hand. “When will I be going home?” she whispered. “Soon, I think,” I said softly, realizing that I was not thinking of the Grosvenor Apartments.

The news which came to me that evening from the faithful friend and the home teacher did not surprise me. They had been with her at the end.

The next morning, I held her hand again, but it was cold and heavy. There were three of us—my predecessor, who had always told me she would help if this task became necessary, the home teacher’s wife, who was responsible for clothing at the temple, and I. Sister Macaulay was not there, even though I hope she was looking on with approval as we dressed her body in her temple clothing. I had wondered whether I would ever have this experience and how I would react. My actual feelings were very different from those I had anticipated. I felt curiosity but no dread. I felt that I wanted to do this last thing for her, and I would have been disappointed if her family had not agreed.

I am very grateful for that experience. Perhaps many believing people have wondered, as I had, whether their faith in eternal life would withstand the test of the reality of death. When we entered that bare room and I looked for the first time at the still body and waxen face on the table, the thought came with great force—”How could anyone suppose that this is all there is?” She was not there, not the friend we had known. And she was surely happier now. We completed our work quietly, without tears. That evening, we veiled her face and said goodbye.

***

Sister Smiley and Sister Macaulay, then, both gave me the gift of new faith—faith in the reality of revelation in response to righteousness and faith in the reality of the immortality of the soul.

Sister Macaulay’s death was also the end of a chapter for me. A month later, I was released. There were no speeches, no trumpets, no tremblings of the earth. There was a brief show of hands in a perfunctory “vote of thanks”; a few people stopped to say a word to me after the meeting, and it was over. I remembered my younger brother’s words when I had first been sustained: “They call it the Relief Society because it’s such a relief when it’s over.” It was a relief, and it felt right. We left on a family vacation, and it was fine to be able to enjoy completely these dear people who had seen it through with me, free of list-making and stock-taking. It was good to know that friendships made would not be lost as the mantle passed to someone else. There would be many good memories, many good stories to tell, and many to keep to myself. Now it was time to get on to something else. I got the children off to school and took out the typewriter.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue