Articles/Essays – Volume 18, No. 4

Hozhoogoo Nanina Doo

Max Hansen dipped his brush into the can and reached to the ceiling, spreading paint thickly and smoothly across the plyboard surface. He paused a moment, listening to a faint tapping sound. Rain? No. A loose strip of metal or maybe a tumbleweed blowing against a window. With his free hand, Max wiped the sweat from his forehead and squinted at his paint freckled watch. Eight-thirty. He still had to finish the west end of the ceiling where the rollers hadn’t reached. Another four or five hours, at least. But it was his last night on the reservation (his very last, this time), and he was determined to finish. Even if it took all night. He would finish.

Max dipped the brush again and spread more paint. He hated painting. And this part was the worst, the touching up. Dip and spread, dip and spread. It took him forever to cover the bare spots and just as long to drag the ladder around. Slow slow slow.

He had been at it nonstop since dawn. A thousand things had been going through his mind, but at the moment—dipping again, spreading again—he remembered the day he punched the medicine man in the mouth. Poor Ben Notah, the old shicheii. The only tooth he had left and I had to go and knock it out. That was a bad one, Father. Even under the circumstances. I knew better. Or should have. It was . . . circumstances. That was the turning point. If I’d controlled it, if I’d stopped it then and there . . . things would be different now, I think. I’d be different.

Weary, woozy, Max stroked the brush directly overhead. Bits of white paint speckled his face, one or two catching him in the eye. Blinking his eye clear, he looked down at the gym floor — row upon row of old linoleum tiles, chipped, cracked, faded to a bleak beige, perpetually coated with dust, some missing, leaving black tar marks and the overall impression of an unfinished puzzle. Cheap, like the rest of the building, a full-sized churchhouse with a chapel, steeple, classrooms, and a “cultural hall.” But cheap. Plyboard and cinderblock.

Once again, Max began counting the beams in the ceiling. Counting helped pass the time. How many brush strokes to paint one panel, how many to cover ten feet of trim? Thirty-six beams ribbed the A-framed ceiling. He had barely started beam number thirty-five. Working fast, he could paint one every two to two-and-a-half hours. Faster if I wasn’t so damn finicky. I don’t know why. This far off the ground who’s going to notice? Max looked down at the deteriorating floor, then up again. Except me. And You. Thee. Sorry. The damn, too.

Calculating the hours he had spent just this week alone, Max felt overwhelmed. The gym had never seemed very big to him until he had started painting it. Then it had taken on cathedral proportions. He’d be here forever: six, seven, maybe eight more hours. It was Saturday night, but if he had to work on into the Sabbath, well . . . It’s for the kingdom, right?

Slipping his free hand under his t-shirt, Max gave his sweat-drenched garments a tug. They tore from his skin like adhesive tape. He ran his hand across his forehead. Painting was bad enough, but monsoon season made it torture. Sticky, sweaty jungle heat. No air-conditioning, no swamp cooler. Not even cross-ventilation. All the window cranks had been broken off — by vandals, mischievous kids, overzealous basketball players. Max had refused to have them replaced until more members — meaning more Navajo members — pitched in with the branch budget. Now in mid-August he was paying for his principles. During the past week, the sweathouse effect had cost him so much in body fluids that his skin seemed to have shrunk to the bone. He no longer looked skinny but skeletal, as if he’d been on a hunger strike. His face, usually summer tan, looked pale, almost gray, and whittled to the bone. His blue eyes looked neutral. Washed out.

Max dipped his brush and slapped it against the ceiling. Five hours, he reassured himself. Five. Then he would lock up the church for the last time and walk back to his Bureau of Indian Affairs trailer, which he would also lock up for the last time the next morning, and then drive south to Tucson. Away from that thankless, endless classroom in the school that was in no better shape than the chapel. Monday morning he and Melissa would board the 747 to Hawaii for a long-awaited and well-deserved second honeymoon. Without kids, without Indians. Even if we can’t afford it. After ten years . . . Alma and the sons of Mosiah invested twice that in the Lamanites, but compare the dividends. When I first came in ’73 we had five coming out to priesthood meeting. Now we’ve got four, all different. They come and they go. Commit and poop out, then commit again.

Ten years. In that time he had seen dozens of Navajo families join the church; none had remained active. Hundreds of Navajo kids had been baptized and bussed off on Placement; hundreds more had been bussed back home. Some graduated, then fell away. A few went on to BYU, and fewer still managed a temple marriage. Of these, a handful had forsaken the reservation. The others had returned and, in time, had sought out the peyote meetings, the squaw dances, the bootleggers . . . . Two steps back for every one forward. Leaning haphazardly against the trading post, red-eyed, smiling his yellow smile, Natoni Nez once summed it up perfectly: “Brother Max, out here the possible is impossible!” True pearls of wisdom from a drunken Indian. I don’t know. I must be crazy, perched up here on a ladder twenty-five feet off the ground. The heat’s getting to me. Or I’m getting old. Thirty-five and what have I got to show for it?

Thirty-five. Ten years. No active converts. Except for Sherman Tsosie. Max’s first and last counselor, his only active Melchizedek Priesthood holder. Portly and pot-bellied, his prickly black hair glistening with oil, he would strut into the chapel every Sunday in a blue leisure suit, sunglasses, and cowboy boots, greeting Max cheerfully, “Ya-tay-ho! Ya-tay-ho!”

The chief. Heart and soul of the branch. Pounding the pulpit in Navajo. Five years ago Max had baptized him and a year later Sherman had taken his family through the Mesa Temple. If anyone was ever ready. . . . Then, just before Christmas last year, he left home. Just took off. Went a-whoring. Like the others. I thought I knew him better. I thought I. .. .

Max wiped his forehead again — dip, spread, wipe — and added a few more strokes until that section of the beam was thickly and evenly coated. He climbed down the rickety ladder, careful to compensate for the two missing rungs, and moved it a yard or so further along the drop-cloth. Uncapping the lid on the five-gallon bucket, he propped it on his thigh and carefully tilted the mouth. Why am I doing this? And why alone? Because no one else would . . . because the project had been dragging on for five years now . . . because it was his last night on the Rez. . . . Fresh paint plopped into the can. Then he heard something else — a vague rumbling outside, then a small explosion, followed moments later by another, like delayed artillery fire. He ignored it and re-capped the bucket.

The work had started with a bang, anglos and Navajos working side by side every Wednesday night and all day Saturday, like the Nephite society. But enthusiasm soon fizzled and the churchhouse sat four years half-finished. Half-assed. Like everything else around here. And it wasn’t even my project. Jeff Peterson’s. The CPA from Salt Lake. Married to sour-faced Marie, who sat in the back pew scowling every Sunday. Big. Huge. Permanently pregnant. They couldn’t wait to get out of here. Peterson the big-plan man. He started the whole thing, called it a vision. Then moved back to Utah and left me holding the bag. Me and Melissa and Steve Adams. And Sherman. He was there too. We all stuck it out. Peterson’s vision became our nightmare. The other anglos said they were burned out and wouldn’t lift another finger until more Lamanites helped out, while the Navajos said they had more urgent business, like hauling wood and water, going to rodeos, or to yeibicheii dances . . . or they just didn’t show.

Max and his faithful crew of three had managed to complete the exterior and half the interior before abandoning the project halfway through its second year, just before Max was called as branch president. I never officially said, “No more!” One Saturday was cancelled for a district basketball tournament, and the next for Tsidii’s funeral, then we never started up again. I guess I wanted more Navajos too. And I pooped out, just didn’t care anymore — about anything. And there was Tsidii, you know.

So for the next three years the churchhouse had remained a half-painted eccentricity. Then, one hot afternoon last June, Max went to the trading post and checked the mail — a bill from Navajo Communications, a J . C. Penney summer catalog, and a letter from Tucson Public Schools offering him a teaching position. He was stunned. Melissa kissed the letter. Ten years we’d been trying to get out of here and when our ticket out finally arrived I was scared to death. Not of the job but ten years. . . .

The following Sunday when Max stood to conduct sacrament meeting, he announced solemnly: “We are going to finish painting the church by August 10th. All who wish to help beautify the Lord’s house may come on Wednesday nights and Saturday mornings. . . .”

But it was summer. Steven Adams, the seminary teacher, was gone, and Sherman Tsosie was AWOL. So Max and Melissa alone had worked like dogs five, sometimes six nights a week, right up until they had loaded the U-Haul and headed south. For good, they thought. But the painting was not finished. The ceiling. The lousy beams. Thirty-six of them. And a week later, eight days before their flight to Hawaii, fifteen days before his new teaching contract began, Max drove north again to clear up some “paperwork,” though the real reason, the one he couldn’t explain even to himself, let alone to her . . . Forgive the deception, Lord. Does the end ever justify the means?

He had arrived a week ago Sunday. Early Monday morning he attacked the ceiling, confident he could paint six beams a day for six days. Six times six and he could be home by Sunday evening as he had promised. But the work dragged, and twelve-hour days stretched to fourteen and fifteen hours. On Friday he ran out of paint and had to drive a hundred miles into Gallup to buy more. The trip cost him half a day, three beams. Saturday morning when he stepped inside the gym, the south windows tinged with dawn light, a rose quartz reflection, he found himself staring up at nine unpainted beams. Nine times two equals eighteen hours, or times two-and-a-half equals twenty-four hours, or times. . . .

Max glanced at his watch. 9:35. At this rate I’ll be here till Monday. Or New Year’s. Father, couldn’t you maybe help speed things up a bit? I know, I know: faith precedes the miracle. And if I’m so fired up to finish, why am I standing here staring at a ceiling I have no business painting in the first place? He had already moved his family and his furniture, turned in his class room keys to the principal. He had even given his farewell address at church. That was the toughest. All alone up there, hung out to dry.

He had often wondered how it would feel to stand at the pulpit for the last time, looking down at the familiar faces. But that morning he faced a congregation of strangers, missionary contacts, one-timers. A helpless, pointless finale. My talk was way over their heads—way over: “After living two years in solitude in a humble, home-made cabin on Walden Pond, Henry David Thoreau abandoned his life of spartan simplicity. When asked why, he explained that he left not because he found that life-style disagreeable but because he had other lives to live. I believe I’m leaving the reservation for the same reason. . . .”

He rambled on toward his real, final message, a scathing condemnation for their promiscuity, drunkenness, irresponsibility, slothfulness, wife and child abuse, deceit, jealousy, neglect, lack of commitment—the whole gauntlet of social and moral crimes. But as he looked out over the audience, the men in blue jeans and cowboy hats, the women in drooping skirts and shawls, many of them smelling like campfires, they took on an aura of innocence, became children in his eyes.

“I just want you all to know that I . . . I love each and every one of you. . . .” The great cliche. The cop-out. As if you can sincerely love someone you don’t know from Adam, Eve, or Jake the Silversmith. But I did. At that moment I truly did.

Afterwards, moving through the crowd of shy strangers, he felt a warm hand touch the back of his arm. The touch was distinct, apart from the random rubbing of the crowd.

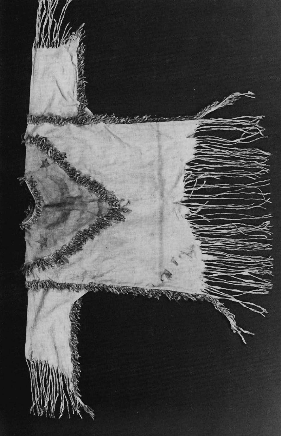

Turning, he saw an old woman, a saani in a shiny velveteen blouse and pleated satin skirt, blood-red, with a squash blossom necklace as big as a harness bearing down on her sagging breasts. Her face, ridged with wrinkles, was long, flat, caramel-colored. Her silver hair was knotted in back with fresh white yarn. She looked at Max, her eyes inscrutable as a Chinese matriarch, stern but sad. I hadn’t noticed her during my talk. It was like she’d come from nowhere. But I knew I’d seen her before.

She greeted him with a hand touch and called him shiyaazh, my son. She spoke in Navajo as if he could understand every word. Before he could place her face, someone called his name and he glanced away, only for a moment. When he looked back, she was gone. Vanished. Like a ghost. If I hadn’t actually shaken her hand. . . .

Max could recall only a fragment of what she had said—hozhoogoo nanina doo. Even with his limited understanding he could decipher it, more or less, but had asked Dennis at the boarding school for verification. “May you go in beauty, harmony, and happiness.” Unusual, Dennis said. Not your typi cal farewell. It echoed the closing lines of the Blessingway ceremony. The words didn’t throw me, but why did she say them to me, a bilagaana, a stranger, whispering as if she were passing on a secret?

With his fist, Max hammered the lid snugly back on the five-gallon bucket. Brush and can in hand, he climbed back up the ladder, this time planting both feet on the rung above the scarred red decal that read: CAUTION: DO NOT STAND ON OR ABOVE THIS POINT. As he painted farther from the wall and nearer to where the twin beams met, he had to climb one or two rungs higher until, painting directly under the apex, he was standing on the very top rung. If I fall and get killed, I’ll catch hell from Melissa. In this life or the next, one way or another, I’ll catch it from her.

Stretching his arm as far as he could, Max spread more paint. At each ladder setting he could cover about seven feet, stretching three-and-a-half feet either way. It took four settings to reach the apex and another three to the opposite wall. Seven settings, wall to wall. Seven times two minus two settings already . . . twelve more times up and down the ladder. Four hours, twelve settings, three settings per hour, seven settings per beam, seventy-two settings per day, 365 days per year times seventy-two times ten years. . . . Max’s eyes traveled hopelessly across the ribbed ceiling, down the plywood walls, across the dusty floor. Ten years, and what have I done? Endured to the end, and that’s about it.

The end. Bittersweet, like the pre-rain fragrance outside. All week, big dark thunderheads had migrated like giant herds from west to east across the sky, blotting out the stark blue. And every afternoon, as if in anticipation, the sun-scalded earth released that same premonitory smell, bittersweet, sexual. But the rain had never come. All week Max had listened hopefully to the distant rumbling of thunder. Stepping outside the hothouse gym, he had watched the rain like a vast gray veil hanging from the dirty clouds, every so often ignited by a streak of lightning. But somehow the rain had evaded the little valley, as if this area alone, for some reason, were being denied. I know it’s a wicked and an adulterous generation that asks for a sign, but something, Lord. . . .

Max stretched to touch up around one of the eight ceiling lights. Three years now and only four burning. What does it take to replace a light bulb? What doesn’t it take? Laziness. Incompetence. Apathy. Passwords out here. It wears on you. It wears. Melissa endured like a spartan, but once she was through, she was through: “You’re not going back up there, Max. It’s not our chapel anymore. Let the Indians paint it — if they care.” It gets everyone eventually. Some sooner than others.

Elder and Sister Crawford from Wyoming. As broad as he was tall, Elder Crawford always looked as if he’d just come in from the fields and had thrown on a suit without showering. Winter or summer, sweat stippled his crew-cut hair and oozed from his brick-red bulldog jowls. His belly curled like a giant lip over his thick leather belt. Max first met him on a Sunday morning as he nervously paced the floor of the tiny trailer where the Sliding Rock Branch met for one hour each week. He was chewing a toothpick, fretting, stewing, his blue eyes darting between the clock and the lone family that had straggled in, quiet, unconcerned, just before noon for a meeting scheduled to begin at ten.

Later, in the Crawfords’ cramped one-bedroom trailer with a bathroom no bigger than a coat closet, Max asked cheerfully, to make conversation, “So how long have you been out?”

“Two months,” Crawford answered grimly. “And nine-and-a-half to go!”

Max chuckled. “You’re already counting the days.”

Crawford fired back humorlessly: “You’d better believe it!”

He caught me totally off guard. Most couple missionaries shoulder it in silence or try to laugh it off. Some even find their niche. Elder Robertson must have fixed half the pick-ups on the Rez. Driving to work on snowy mornings, I’d see him out chopping wood for old Sister Tsinajinnie. But Crawford was something else.

“In the M.T.C. they told us these people were crying to hear the gospel—just crying to hear it! We was all set to come out here and set the mission on fire! But I’ll tell you . . . .” Crawford shook his head despairingly, snorted, worked some phlegm around in his mouth.

“I’m surprised they said that,” Max said, glancing over at Sister Crawford, quietly knitting in the corner. Compared to her husband, she looked frail and timid, a dwarf in below-the-knee skirts as drab as her poodle-cut hair. But of the two she was the rock.

Max tried to give Elder Crawford some encouragement. “I’ve only been out here a couple of years, so I’m no expert. But if I’ve learned one thing, it’s don’t try to change them overnight. You’ll just get frustrated. It was fifteen years before these people would use a can opener, let alone accept the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

Elder Crawford’s fat red finger jabbed like a dagger. Max flinched. “That’s right!” he growled, his face growing redder by the second. “They’re too old fashioned! Stupid is what they are! I seen some yesterday trying to shear sheep with them rusty old hand shears. Don’t they know how to use electric shears?”

“Where do they live?”

“Up to the mesa.”

“Maybe they don’t have electricity.”

Elder Crawford’s fat lower lip curled indignantly. His wife looked up from her knitting, then down.

Max continued, “From their perspective, what do we really have to offer them? They don’t need temporal help. Food, clothing, medical care — Uncle Sam takes care of that with no strings attached. No mopping up the church house or washing baptismal clothes in return.”

Elder Crawford nodded and his vulcanized face simmered.

“When they join the church,” Max continued matter-of-factly, “they have to forsake squaw dances and ceremonies and Sunday rodeos and picnics and good old Garden de Luxe. All the things that make life enjoyable. And for what? The promise of eternal life? Sorry. It’s now or never in their minds. They don’t even have a future tense. Not like ours. We even lose out spiritually. The peyote church offers them automatic visions. We can’t guarantee that.”

Forgive the blasphemy, Father. I was telling it like I’ve seen it, not to stir up dissension but to offer some consolation maybe. And he missed the irony. Baring his crooked yellow teeth, his face flushed and swollen, ready to explode: “That’s exactly what I been telling these people! I told this one lady the other day: ‘What do you think this church is all about? You expect the church to give you everything without you making no sacrifice! What kind of church don’t make you make no sacrifice? You expect us to come out here and wipe your little behinds?'”

Max winced. He knew the type: they drove up at all hours of the night in battered one-eyed pickups or fresh-off-the-line models, the cowboy-hatted husband slouching in the cab, aloof, while his wife in blue jeans and a windbreaker knocked on the door, usually with a sandpainting or a rug or jewelry to pawn or sell. And even if she didn’t, if she was just begging a buck to go over the hill and have a good time. . . . He broke the rules, Rez protocol.

“You didn’t really say that, did you?” Max asked, straining to maintain a smile.

“I sure did!” Elder Crawford cocked his head proudly, as if he’d just borne his testimony alongside Abinadi. Sister Crawford continued knitting.

I wondered then why You sent people like Crawford out here. Maybe to open those slit eyes of his. Back home in a good solid Mormon ward on good solid Mormon soil, where values and ideals are mutually accepted and love and compassion cut and dry, we get to thinking we’re pretty good Latter-day Saints. Then welcome to the Rez! A brand new ballgame with a whole new set of rules.

Elder Crawford continued: “I could say no to my bishop, but I couldn’t say no to the Lord!” Then, musing on his home town: “That’s paradise up there. Just paradise. But this here . . . . ” Mormon purgatory? I promised myself I’d leave before I ever turned into a Crawford. Did I hang on seven years too long?

Max climbed down the ladder, moved it another few feet, and climbed back up. Just the thought of Crawford’s burning red cheeks made Max feel ten degrees hotter. He wiped his sweaty forehead. Faint drops sounded for a moment like rain, but then Max realized they were drops of sweat or paint or both splashing on the canvas below. He thought of Christ in Gethsemane, the blood oozing from every pore, then felt a sense of shame at the trivia of his ordeal. And what have I learned in ten years — ten times longer than Elder Crawford?

In ten years, he had entered the shacks and hogans countless times, at all hours and in all furies of weather, to bless the sick or cast out evil spirits or nullify witchings. Every year he had exhausted his annual leave with the BIA to conduct funerals for the old and weddings for pregnant brides and their reluctant boyfriends. He had visited the elderly, the widowed, the sad, the disfigured, the handicapped, members or not. And he had performed miracles.

No. A miracle had been performed through him. He remembered that rainy night. A late lyiock on his door. Sister Watchman, short, squat, a Pendleton blanket over her shoulders and a scarf over her head, dripping wet, smelling of body odor, wet wool, mutton stew. Her daughter, Coreen, fourteen, dripping beside her. “My mother wants a blessing,” she said.

Usually she wanted a couple of bucks to go visit Curly Floyd, the boot legger. Usually she would have unclasped the turquoise bracelet from her wrist, her only valuable, and silently offered it to him for pawn.

“Come in,” he said. “Woshdee.”

They did, but stopped on the small linoleum square just inside the door.

Their Fed-Mart sneakers were caked with mud.

“What’s the problem?” Max asked.

Mother and daughter whispered to one another in Navajo. Then the daughter, to Max: “Cancer.” Motioning shyly to her left breast. “Here. They’re going to operate here.” She made a slicing movement with her hand. Rain pelleted the trailer. Setting a chair in the middle of the living room, Max instructed the daughter to have her mother sit down. He laid his hands on the woman’s head and blessed her in the name of Jesus Christ — blessed her to receive the best and wisest medical attention; blessed her with the strength and courage and faith to cope and carry on; blessed her family, her friends, the doctors. . . .

After he finished, Sister Watchman stood up, neither smiling nor frowning, and whispered to Coreen.

“My mother says thank you. She says she’ll be well now.”

Silently Max watched mother and daughter step out into the rain, too stunned to call them back to clarify the blessing, the stipulations, the no guarantee clauses. She ignored the fine print, the “if it be Thy will,” “according to thy faithfulness.” She was expecting a miracle, for crying out loud! A miracle! You don’t just—well, of course, you can, but. . . well. . . .

“Hagoshi,” was all she said. It is well.

Sister Watchman returned to her loom and her livestock, and the next time Max saw her, she was alive and well and double-breasted, shooing her sheep along the wash.

He had almost finished another section when a nagging itch developed in his lower back. Irritated and unable to reach it, he threw his brush into the can, descended the ladder, and walked out into the hot, sticky night.

The full moon gazed down milky yellow, like a sick idol, while a handful of stars boiled around it, the remainder blotted out by the congregating thunderheads. On the horizons lights puffed up and faded out, over and over, like a chain reaction of flashbulbs. A muffled rumbling followed, more artillery fire. Watching and listening Max felt anticipation and apprehension, some thing longed for yet at the same time threatening.

Max stared at the churchhouse. From the foot of the butte, it looked solid and stately, the silver steeple reaching into the heavens. The long A-frame roof, like a transplant from a Swiss chalet, rose boldly out of the horizontal desert and carved a sharp wedge into the night. But he knew its imperfections too well, the gaping fractures climbing the cinderblock walls, the peeling paint, the weeds prying apart the concrete walks, the scabby grass out front. In daylight, naked, the south wing looked more like an Anasazi ruin than a Mormon house of worship. It all seemed so futile. A year after it had been slapped on, the brown trim outside was already flaking off. The Rez had no deference for the holy priesthood, let alone Sears’ Weatherbeater.

He looked across the road at a bonfire outside the Benally hogan. It was big, gold, fluttering like a shredded flag or a maverick sun. A couple of stray dogs were nosing into a tipped trash can. Up on the hill by the water tank, he could hear voices, soft, giggling. A pair of headlights flickered down the road like scavenger eyes. Soaked with sweat, his throat parched as if coated with sawdust, Max closed his eyes and inhaled deeply. A warm wind blew across his weary face, cooling him.

Elder Crawford called it the Land of Desolation, but his head was still in Wyoming, doting on banal Rocky Mountain beauty, snow-capped peaks and pine trees. Yes, it’s a harsh, stubborn, mean, bastard land, a desert, but it’s Yours. Thine. And the beauty was there. In the bizarre sandstone architectures—vermillion castles, leaning towers, onion domes, minarets, a sombrero tilting on the tip of a wizard’s cap. It was in the mesa, barricading the land from the world beyond like the Great Chinese Wall. It was in the colors, greens yellows golds browns reds blues—ever-changing in the interplay of sun and shadow, every shade and tone imaginable bleeding from the rocks, the sand, the sky. It was in the valleys, vast and empty save a hogan or windmill, floating like tiny ships at sea or satellites in outer space. Beautiful, but harsh. Stubborn. Like the people.

He could see that stubbornness in everything, from the tough, stingy sage and rabbit brush that resisted the winds and rain, to the gaping mouths in the sheer, weather-crippled canyon cliffs, to the gnarled rocks and pinnacles, to the juniper trees, whose silver bark splintered and spiraled around contorted trunks. But it grows on you, if you let it.

Driving the empty reservation roads, he had come to relish the ocean-like stretches of land, so opposite the vertical thrust of pines, of mountains, forever forcing the eye upward, heavenbound. When we vacationed in Tucson or Salt Lake, all the neat little suburban neighborhoods with neat little lawns and neatly marked streets and real gutters and sidewalks and concrete everywhere and everything precisely squeezed together without an inch unpaved un planted unaccounted for . . . I got claustrophobia, Lord. And the long tedious hours his parents and in-laws and brothers and sisters and cousins and friends devoted to keeping their yards trimmed and tidy seemed vain and presumptuous. Wasted. Are they neurotic and have I seen a new and better light? Or just become lazy? Caught the Lamanite disease?

He had come a stripling twenty-five-year-old, fresh out of graduate school, with flashing blue eyes and rosy cheeks into which the creases were daily digging deeper. His face and hands had taken on the parched look of the land, without the color. It wears, Lord. The sand in your hair, your food, your bowels. The Dust Bowl blizzards and sweatbox summers. The incompetence. The laziness. The B.S. The hypocrisy and contradictions. The Attakai family, no gas money to drive to church on Sunday but a satellite dish outside their double-wide trailer. Jerry Benally calling at three A.M. : “Go over to the clinic! My brother needs a priesthood blessing!” His brother mashed in a car wreck, his second in a month. The Pampers and pop cans and potato chip wrappers littering Sacred Mother Earth. . . .

It wears. The drunks. The panhandlers. The lukewarm Mormons who supplement the sacrament with peyote chips. Or worse, the members on the books only, strangers cornering me at the trading post, pumping my arm, asking me about my family, my job, the branch. Then: “Can you loan me a couple dollars?” It’s insulting, as if a promise to sit through sacrament meeting is worth five bucks to me. As if attendance is my hang-up. They show up in the pews for the first time in three years and even bear their testimonies—how they went astray but are back to stay now—then afterwards catch me in my office, shaking my hand again, the alcohol still red in their eyes, giving me a song and dance about how they’d quit drinking and are going straight, have just seen Jesus sunbathing in the wash . . . “Because I believe! I believe in Je-sus!” Saying the Savior’s name not like a Mormon, with meekness and restraint, but that canned commercial hip-hip-hurray fanatacism of a Baptist preacher. And inevitably, the request: “So I was wondering if maybe the church could loan me some money.” For a truck payment because no G.A. check this month—computer foul-up. Or to take their dying mother to the hospital. She was dying the last time they tried to hit me up. I’ve heard them all. It wears. The land. The people. It gets everyone sooner or later.

Except them. The People. They endured. In their own passive stubborn obstinate way. Like the grass, the sagebrush, the canyons.

The light on the horizon still pulsed off and on like a stuttering bulb about to black out under the smothering weight of the clouds. It struggled weakly but valiantly. Silently Max urged it to resist.

As he started back to the church, a huge fork of lightning streaked across the northern sky followed by a bigger, brighter one that plunged earthward like a giant talon. A third streak reached down as if to pluck the steeple right off the churchhouse. Defiantly Max moved away from the building and the butte, into an open area where he stood like a solitary pine. He was not afraid but apprehensive, and not of the lightning but of hoping too soon. The moon was gone, buried in black clouds. The sky rumbled, then let loose a barrage of cannonballing booms that shook the churchhouse and everything around it. But that was all. No rain.

He turned and headed back inside. The thunder simmered to a faint echo and the lightning to a few dying pulsations on the mesa. Max gripped the ladder with both hands and looked up despairingly. The beams looked like a prehistoric skeleton. He felt trapped inside the belly of a whale.

He dragged the ladder a couple feet to the center of the gym, right under the apex. Climbing very slowly, cradling the can and brush in one arm, he felt a sour-stomach, acrophobic feeling. His muscles grew limp and feverish, his free hand quivering as it moved from rung to rung. Thirty-five times and I still feel like I’m tight-roping across the Grand Canyon. Peterson promised me scaffolds out here. . . .

Carefully Max crept upwards until he was kneeling on the top. Slowly moving one foot up on the rung, then the other, he raised himself until he was standing erect. He glanced down. The linoleum floor seemed a thousand feet below. Black tar marks glared back at him like Halloween eyes. Slowly, painstakingly, Max touched the brush to the beams, stretching only a foot or two in either direction. Don’t let me down now. Not this close. Ten years. It wasn’t always like this—I wasn’t, was I?

Initially he’d been positive, optimistic. He’d tried to learn all he could about the land and the people. He took night classes in Navajo language and culture. He picked up local hitchhikers and learned to say no tactfully. At church, in talks and testimonies, he constantly stressed unity and the similarities rather than the differences between the Anglo and Navajo members, citing the Zion Society in Fourth Nephi, in which there were no Lamanites or any manner of -ITES: “It doesn’t matter if you’re black white red green yellow or pink-purple-polka-dotted, whether you eat whole-wheat or white bread. We are all bound by a power that goes far beyond any mortal family or cultural ties. We are literally brothers and sisters, sealed to one another by the blood of Jesus Christ. . . .”

At socials he entertained the crowd with slapstick skits and John Wayne impersonations. He made few demands on anyone, even at work, indulging the Church members, shouldering the burdens of a crippled branch with grin-and-bear-it fortitude. But I let little things get under my skin. The mud. The cockroaches.

Ben Notah, the medicine man. Knocking on Max’s door that tragic afternoon three years ago. I never knew quite what to make of Ben. He was a bona fide medicine man, a great sand-painter, the best. But he didn’t look the part loitering around the trading post in holey sneakers and a World War I trench coat that hung below his knees. A wool skullcap covered his half-bald head. He looked like a troll on welfare.

“Brother Max! Ya’ at’ eehl” Smiling, his solitary front tooth Skoal stained, carious, a rotting kernel of corn; extending his hand, plump, crusty, polka-dotted with scabs. “Brother Max, maybe you can help me out? Could I borrow five dollars?”

Before Max could refuse, Ben was making promises: “I’ll bring you two sandpaintings tomorrow. The Buffalo-Who-Never-Dies and the Nightway.”

“Ben, you still owe me a sandpainting from the last time.”

“I’ll bring it tomorrow.”

“Fine. Then we’ll be even-steven.”

Ben looked puzzled but smiled. “I’ll pay you back tomorrow. I promise. I’m giving a lecture on the Blessingway at the Presbyterian Church. I’m getting a hundred dollars. You come too.”

I wasn’t usually that stupid. Or gullible. But he caught me at a weak moment, right in the middle of scripture study, the Sermon on the Mount. I was fasting, too.

Max opened his wallet and took out a five-dollar bill. “You’ll pay me back tomorrow?”

“Honest Injun,” Ben said, grinning.

Max never saw the money or the sandpaintings. And when he looked through the door at Ben’s oily face and his eyes begging pity he didn’t deserve—or didn’t need; him standing there alive and well and breathing inside that porky little booze-abused body while my little Tsidii . . . I couldn’t handle it, Father.

Max’s fist plowed square into his face, splitting it from the top of his lip to the tip of his chin. The medicine man sprawled backwards off the steps and into the dirt where he sat up slowly, ribbons of red trickling down his mouth, looking not angry or frightened but confused. Finally he opened his mouth and spit out his lone tooth; dusting himself off, he hobbled out the gate. Max buried his face in his hands, weeping not for Ben or his daughter or even himself, just weeping.

Another rumble outside. Miming his empty belly. Max sensed the early twitchings of a cramp in his left calf. He closed his eyes and tried to unthink the knot. The day he punched Ben Notah had begun right here. In this gym. This damn gym. He remembered perfectly: chasing downcourt after the speedy guard from Rough Rock; the loud, dull crash just outside the building. Then silence. The ladder—heavy, wooden, left standing from last week’s paint project—now lying on his daughter’s skull, dented like a tin can. Max heaved the ladder aside, but her blue eyes and rosebud lips were already frozen. Melissa, walking over from the trailer, hastening her walk, running: “Max! Oh my God, Max!”

Kneeling in the hot noon sun with the bleeding little head in his hands, Max said, calmly at first, “Go home and get the oil. It’s in the refrigerator, the lower shelf.” Melissa, hysterical, screaming until he screamed back, “Dammit, Liz! Shut up and get the oil!” She ran off. The crowd had gathered, mostly athletic young men with glossy black hair and smooth, sinewy limbs but dumb founded expressions. Max scanned the group hopelessly. “Woodrow!” he called to an elderly spectator who spoke little English. The only Melchizedek Priesthood holder in the crowd. “Come here. Hago!”

But Woodrow backed off, shaking his old sandblasted face. I couldn’t blame him. He still hadn’t forsaken the old ways. Afraid of the ghost spirit. Old chindi.

The others backed away too, silent, as Max placed his hands on the child’s dented skull and, calling her by name, whispered desperately, “In the name of Jesus Christ and by the authority of the Holy Priesthood, I . . . I command you to live. I command you . . . You will have a full and complete recovery. You will suffer . . . no . . . no physical or mental disability. You will. . . .” But he broke down, never finished the prayer. By the time Melissa arrived with the vial of consecrated oil, he was covering the child’s face with his t-shirt. Bad timing on Ben’s part. When he knocked on the door, I could still smell Tsidii’s blood frying on the pavement.

So Ben Notah lost his last tooth. And the next morning Max woke up with a fist the size of a boxing glove. A veteran at mending barroom cuts and gashes, the doctor at the PHS clinic took one look at his bloated paw and smiled: “Who got the best of it?”

He did, Max thought, stabbing his brush at the very top of the apex. Just as painstakingly as he had mounted the top rung, he began climbing down. Two shots of penicillin and my hand wrapped up for a week. A high priest in Israel punching out an old medicine man….

That very night the district president, a stocky little Hopi with a goatee, had knocked at his door.

“Brother Hansen, the Lord has called you to serve as president of the Tsegi Branch.”

Timing. It was the timing again.

“I don’t think I should accept.”

“Why not?”

Max hesitated. “You need a Lamanite.”

“The Lord has chosen you.”

“Are you sure?”

President Seweyestewa hesitated. “Yes.”

He was sustained and set apart the next day.

Max glanced at his paint-freckled watch. Ten o’clock. One-and-a-half beams, ten settings to go. He’d have to work faster—much faster. He climbed back up the ladder. Strange how he had walked across that parcel of pavement thousands of times over the past three years without thinking of the fallen ladder and his daughter’s little head smashed underneath it. Now he wondered how much he had paid for that kind of detachment. Or did I care that much to begin with? I gave it lip service too. Fatherhood, my number one calling; family, my greatest joy. Not really. Not at first. Not until five years ago when our fourth (and last?). . . .

Tsidii Yazhi, the Navajos called her, “Little Bird,” because her hair was so white and stiff and stuck straight out all over, like an exotic bird. I could never pronounce it right, always fouling up the Ts, my awful Navajo. Before Tsidii, fatherhood was a duty, a lot of hassle and . . . adaptation. No, I don’t think I loved her more than the other three. It just took me that long to finally . . . well, delight in them.

Quickly finishing up the section, he recalled how each morning, as he left for work, she would call out to him, “Wait, Dad!” and then lug his volunteer firefighter’s coat and helmet to the door, her face red from the strain, and dump them proudly at his feet: “Here, Dad!” Fetching his shoes. Announcing the first snowfall. Doing forward rolls across the living room floor. Proudly greeting him in Navajo: “Ya’at’eeh, shizhe’e’V Crying when he left in the morning, dancing circles around him when he returned at night. So concerned about him: “Tired Daddy sit down . . . right here!” Maternal little two-year old. It really hit me one night while she was putting her Cathy doll to sleep, just how spontaneous and innocent—pure, how pure she was. And how eventually those cute little arms and legs would grow long and those pinpoint nipples would swell, even her Tsidii hair would grow long and lay flat.

He wept. Not because she would eventually have matured and left him, but because, looking at her, the Tsidii-electrocuted hair, her busy little hands, her unpretentious, dimpled smile, he realized for the first time just how deeply he felt for her. All the kids. Sarah with her studious airs and gangly Mark and Shannon the little gymnast. I finally realized, or admitted to myself, yes, they are my joy, my comfort. And what else matters? Car job money house? But I wonder now if I don’t need them more than they need me. What have I done for them when you get right down to it? Besides exiling them on an Indian reservation? So Sarah can’t take ballet lessons and Mark still can’t swim. They don’t even know who Pac-Man is. Wrong. I won’t apologize for that. There’s more to life than Pac-Man and VCR. They loved hiking the buttes and canyons, and driving up to Tsaile to cut down a Christmas tree. In the spring when the water was running, they’d splash in the wash like little otters. There were powwows and rodeos on weekends, and I took Mark to that Fire Dance. Things they never could have seen or felt in the suburbs. And at least they grew to respect and even love sand and space, seeing thy children in all colors. Not turning up their noses at an outhouse, and the size of a home no big deal, or a woman scooping out her breast to feed an infant during the sacrament. They didn’t cringe at a dirt floor, or pity, and saw how death can have dignity even in a pine box lowered by rope into a hand-dug hole in the dirt. Maybe they didn’t realize it at the time, but when we finally packed up and left, they cried all the way to Holbrook. All of them. Melissa too. . . .

Max climbed down the ladder and moved it along the drop cloth. Nine more settings. Three more hours. 10:35. He gazed about the gym at the faded boundary stripes and speckled free-throw lines. Bits of orange and black crepe paper clung to the near hoop, remnants of a Halloween party long ago.

Mounting the ladder once again, he recalled the district basketball tournament. It had started late. Somehow Tsidii had gotten into one of the five gallon buckets and dripped paint all over the floor. I chewed her out, really yelled at her. I wasn’t ready to show the increase of love yet. No, I don’t begrudge Thee taking her away like that so much as taking her away then, on a sour note, my last words to her, “Shut up! Just shut up and get the hell out of here!” That, to haunt me till the Resurrection. Timing again. Ten years of bad timing.

“There’s more to education than a classroom,” he used to tell Melissa. “Think of the cross-cultural experience the kids are getting. They’ll learn things here they couldn’t learn anywhere else.” Then, half-jokingly, he would point to two dogs mating outside the trading post while a pack of slop-tongued others waited their turn. Experiences. Powwows. Rodeos. Losing a daughter, a kid sister.

He thought Tsidii’s death would be the last straw for Melissa, but he was the one. She had already endured beyond her breaking point. The mud, the wind. Anomie. Isolation. Death came to her as a natural consequence, a fitting culmination. After the initial shock, she had resigned herself. But her suffering had stretched out over seven years. Mine. . . . Another proverb: If your marriage can survive the Rez, it can survive anything.

He remembered (climbing down the ladder, dragging it along, climbing up again . . .) midway through their first year, Melissa, a child in each arm, crossing the muddy compound returning from teaching Primary Tuesday, Seminary Wednesday afternoon, MIA Wednesday night . . . Max drove up just as she lost her footing and slid with the two children across the mud. It looked funny at first, like a Charlie Chaplin stunt. But later, in the trailer: “I’ve had it with this place, Max! I’m sick and tired of buying milk that’s sour because the trading post is too cheap to turn up their refrigerator. I’m sick of the drunks asking me for money every time I go to check the mail and the dead dogs on the road and this godforsaken land and the starving horses with their ribs sticking out and the old men peeing behind the Chapter House and. . . .”

He promised her they would leave at the end of the year. But with skyrocketing inflation and unemployment, a skidding job market and reservation housing dirt cheap . . . You get trapped. Financially, emotionally. “One more year” became a standing joke.

One Sunday morning in their fourth year, Melissa stormed down the hall: “Where’s my slip? No, my long slip! Dammit, Shannon, I told you not to play with it .. . Max, that’s it! I’m not going! I’m the only one who does anything around here. I am not going! Do you hear me, Max? Do you hear me?”

“Loud and clear.”

“I said I’m not going!”

“Don’t.”

“Sarafina Begay probably won’t show up and I’ll have to give her Relief Society lesson — again.”

But that Sunday the Navajos, young and old, poured into the chapel — humble in blue jeans and cowboy boots, a few in mangy suits, old women in velveteen or pleated rags. It was so packed we had to open the dividers and set up chairs in the gym. That Sunday I saw the bud begin to blossom.

And that night, Melissa in bed, feeling guilty, apologizing: “I don’t know what got into me this morning. I haven’t thrown a tantrum like that since high school.”

Sitting beside her, reading scriptures: “Forget it. It’s just the Rez.”

The swamp cooler stirring the musty summer air and bedsprings creaked restlessly in the children’s room. Guilt pangs. I had my share too. All those nights coming home late from church meetings, home visits, painting projects . . . when I could have been with Melissa, the kids.

Trudging through the door at midnight. Melissa waiting up in front of the TV.

“Kids asleep?”

“Since eight.”

“So what’s new in the world?”

“Hostages in Iran, Russians in Afghanistan, inflation up to twenty per cent . . . same old stuff.”

Flopping down on the sofa beside her, looking at bare legs that no longer lit his fire without a concentrated effort. Not because she’d gone to pot after four kids. It was me, Father. Fatigue. Burn out.

“Anything exciting happen tonight?”

“Saw Jerry Yazzie at Thriftway. Billy Tso’s in jail again.”

“Drunk?”

Max shrugged.

“Is he still going to be ordained an Elder?”

“Not now. Not if I have anything to say about it.”

“That’s too bad. He was doing real well there for awhile.”

“They all do real well . . . for awhile.”

His head fell softly on her lap; she stroked it gently.

“Melissa, you’re terrific. It’s not every woman who’d put up with all this.”

“All this what?”

“All this me.” He turned to her with child-like jubilation: “Someday when we’ve got our own house. . . .”

But after their fourth year that line ceased to console her, and by their fifth it was downright irritating, a detonator to quarrels that left the children whimpering in their bedroom. So he had dropped it completely. The line, the promise, everything, until he could finally make good on it. And then it was too late. Almost.

Finishing the thirty-fifth beam, he climbed down again. One left. Confidently he re-set the ladder, but climbing back up he was weakened by a strange feeling that the beams had somehow multiplied, that there were forty, fifty, a hundred maybe. He told himself that was crazy, impossible. He dipped his brush and spread. Mountains and valleys, Father. Up and down, up and down. Melissa and me.

There were moments. Summer mornings when her body, like the land, lay deep in shadow, fresh, fertile, the moisture on her brow like the dew on the sagebrush, and the line of her suntan a white criss-cross on her sleek back. The phone off the hook, the dog thumping its tail against the front door, the swamp cooler humming down the hall. Slowly she would awaken to his touch; then, as if he’d pressed a magic button, her cool flesh, ripe from a long night’s rest, would awaken, catch fire and envelop him so suddenly that he was always caught a little off-guard and could never think through or fully feel what was happening though he always relished it, those few intimate moments when together they withdrew from the world.

Now Melissa was in Tucson with the kids. She didn’t want him to go back. Maybe she was right. Maybe I should have left it to the Indians. It’s their church, their land. All right, Thy church, Thy land. But why not share the blessings, right? I should have listened to Melissa. I should always have listened to Melissa.

Max paused, gazing at the ceiling, at the eight caged lights, the thirty-six oppressing beams. Where’s the still, small voice telling me, No no no, noble Max, thou hast done well, my faithful if sometimes begrudging servant? Melissa. Let me see Melissa again. And the kids. Sara, Mark, Shannon. The kids I want to see. Tsidii too. No, I won’t go into that.

He finished the section in record time—fifteen minutes. Six more settings, one more apex. But the heat and dehydration were getting to him. Halfway down the ladder green and black spots collided before his eyes. He miscalculated the missing second rung and almost fell. Time to end his fast—he’d been going without since dinner last night—take a drink at least. He re-set the ladder and walked down the hall into the men’s room. He turned the faucet on cold and waited several moments to see if it would run any cooler, though he knew it wouldn’t. A year ago he had disconnected the drinking faucet in the hall saying too many kids (yes, his too . . .) played in the water and slopped it on the floor. The real reason was the few adults who had made the porcelain trough a spitoon for their chewing tobacco.

Max filled his mouth with water but did not swallow. He swished it around several times and spit it out. The water was warm and bitter, with a rusty, metallic flavor that complemented the putrid smell coming from the ladies’ room. He peeked into the lone stall. The toilet hadn’t been flushed, probably since last Sunday. So what’s new?

Pushing down the plunger, he tried to laugh it off, but nausea forced him out. He collapsed against the wall, his hands, face, and neck soaked with a second sweat. His lids clenched shut against his will; the room went black. Bending at the waist, he dipped his head between his knees and left it there until the darkness cleared and his eyes reopened.

Straightening up slowly, he returned to the gym and climbed back up the ladder, thinking how many times in the last ten years Melissa’s old college roommates had unknowingly broken her spirit with letters describing their new homes on the hill, then, later, how they were redecorating them, and later still, their new homes higher on the hill. . . While we bought furniture at yard sales and drove our Ford into the ground. Ten years and what have we got? A cradleboard, a couple of sandpaintings. Not that we need a Cadillac—that’s the last thing. But it would have been nice—easier for Melissa, I think—if at the end we had had a little nicer house . . . something besides memories, a headstone.

The world had passed him by. In a decade his younger brothers had graduated from law and medical school and had started thriving private practices. His grandmother wrote often reminding him of his choice blessings—beautiful Melissa and the children and his wonderful “mission” among the poor Lamanites . . . . But then, inevitably the marvelous toys and bicycles and Baby Dior outfits and canopy beds his brothers had bought their children, not to mention her new microwave oven, Christmas compliments of his younger brother Robert the attorney. . . .

To Grandma Hansen, “things” are blessings from above, the temporal reflecting the spiritual. A mixed message. “The humblest hogan can be a temple if Thy Spirit there abides.” Elder Crawford badgering the peyote people: “Look what your crazy religion’s gotten you! A shack! A hole in the ground! You’ll never get ahead. . . .”

Working quickly, Max touched up another section, descended, dragged the ladder along the drop-cloth, and refilled his empty can. He hesitated at the foot of the ladder, then detoured out into the foyer and slowly opened the door to the chapel.

He switched on the light. Large and humid, with a beamed ceiling even higher and more severely slanted than the one he was painting, the chapel seemed like a vast cavern. The plywood walls smelled like fresh paint though it had been two years since they had been refinished. From the base of the pulpit, a framed portrait of the Savior gazed at him solemnly. Max looked away. The quiet room demanded a reverence that was rare those chaotic Sunday mornings he presided over the services. Softly, he walked down the aisle, a light film of dust recording his footsteps. He gazed at the familiar old pews of fading varnish, the half-husked covers of the hymn books, the organ no one could play. A few nuggets of sacrament bread had gone stale sitting in the silver trays. Sand and dust coated the window casements. A torn and tattered divider, like a ragged accordion, walled off the chapel from the gym. Cheap, second-rate, abused. But Max felt oddly at peace within the room, perhaps because of the many imperfections. The silence was so dense that exterior sounds seemed amplified in contrast — a knock on a door, a passing car, powwow music from a nearby trailer.

Max switched off the light, closed the chapel door, and returned to the gym. Somewhere along the way I lost my innocence. I came here a man of faith and planted what I thought was a good seed. But the soil, and this ten year drought—ten times two hundred years—I couldn’t get a bud let alone a blossom. Sagebrush and rabbit grass. No roses. Everything withers—everyone. My high school buddies went to Vietnam; I wound up in Indianland. They lost their legs in a jungle on the other side of the world; I lost my marbles closer to home.

As branch president he started the services at nine A.M. sharp, whether two, three, or a hundred were present. He chastized teachers who shirked their Sunday duties and lowered the boom on members who doubled with the Native American Church. He cut off welfare assistance to inactives and tightened the screws on returning Placement students who ditched church during the summer. He made enemies. Instead of Hastiin Nez, “Tall Man,” behind his back they called him Dooldini, “SOB.” Twice his tires were slashed and his windshield broken. One morning he found a mangled cat’s head on his doorstep; another time, a wad of tin foil with strands of human hair wound around a piece of bone. Still, he played hardball, cried repentance from the pulpit, laid down the law: “As members of the church, fellow citizens, we’re all judged by the same standards, regardless of race, creed, color . . . So I don’t want to hear any more of this ‘I was witched’ business. We’re all free agents, accountable for our own actions.”

Under Max’s stewardship polygamists, adulterers, fornicators, bootleggers, unrepentant sinners of every make and variety were called to court and excommunicated.

Max climbed down and moved the ladder along, clear to the other side of the gym. He would work inward, from the wall, towards his grand finale. I went off the deep end, didn’t I? Not that they didn’t deserve the scolding. But not the anger. Venting myself on them. That day at the trading post when Jimmy Yazzie’s pickup stalled and the two women were out there in the snow trying to push-start it, I sat in my Fairmont and watched, thinking, “Dumb dumb dumb . . . Drive your damn truck to death, never change the oil, never tune it up. Then blame it on the dumb white man who made the truck when it konks out on you.

Or Sadie Curly, fifteen, knocking on Max’s door at midnight: could she borrow four dollars to buy Pampers for her baby? A baby she shouldn’t have had in the first place. Driving around in her boyfriend’s red sports car. I gave her the money, just like I finally got off my rear and gave Jimmy a jump-start. But the feelings . . . “Why the hell don’t you use cloth diapers — I do! What about your big-shot boyfriend — he gave you the baby, why not the diapers too?” And when I saw the old matriarchs, big as washing machines, taking bows at American Indian Day, I didn’t see dignity but obesity. And superstition, fear, futility. And that was my sin, my failure, not theirs.

Max slapped his brush against the ceiling, sending a flurry of white speckles through the air. Father, I don’t. . . no, I don’t regret for a minute Steve Natai or Ben Jumbo, the peyote people. Or Jake Bedonie with three wives and so many kids he can’t keep their names straight. Or even Clara Tullie who did and didn’t understand. But Sherman. . . .

Late one Saturday night, Max noticed a light on in the churchhouse. Walking over, he saw his first counselor all alone, running the buffer up and down the chapel floor. Wearing sunglasses and those crazy Tony Lama snakeskin cowboy boots, his hair as shiny as black wax, plastered flat on top and bristly on the sides. Those others could have cared less about their membership. They yawned, belched, “pass the bottle.” But Sherman had come so far, had tasted thy fruit. He cared. And I didn’t want to, Father, convene that court. I didn’t. So I had to. I would have done anything to let that cup pass. The others, no. I grew horns and fangs and turned into Elder Crawford. Still, I could bless them, heal them. You could. The adulterers, the fornicators, the drunks, the polygs. A terminal woman half in her grave who now passes out in front of the trading post every afternoon, a bottle of T-Bird in each hand — through me you healed her but not my kid. No. Who am I to question thee? Shall the thing formed say to thee who formed it, why why why why why? When maybe it was me all along. Simple faith. Thinking deep down no no no instead of yes yes yes. A mustard seed and I didn’t have it.

Working towards the last apex, Max dipped his brush and stretched far to the right, trying to catch a crack between the ceiling and the beam. A rim of sweat that had been gathering on his forehead suddenly dropped into his eyes, forcing him to clench them shut and wait for the salty sting to pass. Nausea overcame him. The green and black dots reappeared. Hurrying, he stretched an inch too far with the brush. The ladder tilted. He drew back but over compensated to the other extreme. Two of the four legs left the floor. The wooden skeleton began falling like a tree. Father! Father! No no no!

Desperately, he heaved his weight and managed to counter the tilt. After rocking to and fro on its four clumsy feet, the ladder finally came to rest. Max steadied the can of paint, laid his brush aside, and tightly closed his eyes, trying to regain his composure as tiny millipede legs ran hot and cold up and down his spine. Not now. Not this close. He picked up the brush and with renewed vigor finished up the section.

Memories crowded in. A summer baptism, afterwards, when he grabbed Loren Benally by the nape of the neck and the seat of his pants. The little nerd, stealing my notes during the opening prayer so I had to speak impromptu.

It gave Max great pleasure, that hot August night, to heave Loren into the algae-stained baptismal font. But his sister, Christine — when Max and Elder Sprinkle, the young missionary from Idaho, grabbed her by the arms and legs to throw her in too, she fought back. “Crazy squaw!” Max yelled jokingly though he let go not so jokingly, not for fear of the fourteen-year-old’s thrashing feet but another, darker fear. Wearing those short shorts with those glowing brown thighs . . . but that was such a dark dark time for me, back then.

Max gave the section a final swipe with his brush, then climbed down and moved the ladder under the thirty-sixth apex. For the very last time he climbed back up.

His hands and legs were shaking when he reached the top. Dabbing paint into the wedge, he struggled with more memories: sacrament meeting the next day, towards the end when the entire congregation — even the fidgety comic book kids in back — suddenly hushed as Ronnie T., the cowpunching Chero kee, strolled up to the stand on bowed legs. Half-way through his testimony his mean, bulldog face with the flat pulpy nose contracted like a fist and with tears streaming down his mud-red cheeks, he began apologizing — to his wife, to his children, to God, to President Max . . . Why me? Especially in my state of mind and heart. And for what? Not doing his home teaching? Having a few crosswords with his wife? For taking a nip on the sly?

Max on the stand rubbing his palm across his brow, gazing down, praying for a corner to hide in. After the meeting, he made his confession, one on one, to the Cherokee: “Ron, I’m telling you this confidentially, as a friend . . . You may think I look holy and happy and spiritually in tune, all dressed up in a suit and tie on Sunday morning with my little family. But the truth is .. . there have been times when Sister Hansen and I have had knock-down-drag outs right outside the chapel doors. I’ve had to pray and conduct meetings with my own curses still ringing in my ears. And if you don’t think it’s hard, pasting a smile on your face and shaking hands and trying to look as if all’s well in Zion when you feel like a cesspool inside. . . .”

Alone in Max’s office, the two men knelt together in prayer, then departed, Ron bleary-eyed. Being imperfect, the higher we aspire in love, com passion, morality, and general human decency, the bigger hypocrites we appear . . . That used to be my rationalization, so I could sleep at night. But I wonder now. . . .

Max wiped his forehead and studied the narrow crack where the two beams joined at the apex. For a moment he was tempted to leave this last little spot bare, unfinished the way the Navajo did with their rugs and sandpaintings, always leaving a small soul outlet. But that’s them, not me. Not Hastiin Nez. Dooldini. Bilagaana Blue Eyes.

He dipped the brush deep into the can and in one swift thrust, like a fencer, sealed the crack. He withdrew the brush and immediately a chain of tiny holes appeared. He thrust again. A third time. A fourth. Sealed! He held the brush in his right hand and the can in his left, so his body formed a cross high atop the ladder. The brush fell to the floor, hitting the drop-cloth with a dull thud.

Climbing down seemed to take forever. For every rung he had climbed up, there seemed to be three going down. The wooden bars were hot irons to his grasping hands. He saw the black and green spots again, then hazy gray light. Then Elder Crawford in a pea green jumpsuit, his head under the hood of a Chevy LUV pick-up. Detaching himself so totally from the land and the people, he had been relegated to full-time missionary vehicle maintenance. Passing through, Max had stopped by to say hello.

“Ya’atfeeh, hastiin! I hear you’re going home soon.”

Elder Crawford didn’t answer for some time. He wasn’t advertising the fact he had requested an early release. His head still under the hood: “This is what I sold half my property for — to come out here and check dipsticks.”

Later, a week before returning to his Rocky Mountain paradise, he pulled his head out just long enough to confess his failure: “I hate Navajos.” Not derisively or vindictively, but sadly.

Max folded up the ladder and set it down against the wall. He rolled up the drop-cloth and hammered the lid tightly on the five-gallon bucket. Gathering up the brushes, he carried them into the janitor’s closet and dumped them in the sink. He turned on the faucet. As the water struck the brushes, milky fluid spiraled down the drain. Fumes from the vats of floor wax and detergents sent sour nausea and dizziness through him. The close-confined walls began tilting sideways. He slipped to the floor. It was my job, my calling. But who was I to judge anyone, least of all these people? Okay, so a lot drink and pray to peyote and rodeo on Sunday and breed like dogs—all the fatherless children! But the good, the humble, the compassionate. . . .

Delbert John’s funeral. Max driving down alone to the hogan to discuss arrangements with the family. There must have been a hundred people crammed in there. Family, friends, neighbors, all ages, bundled up in old coats and blankets. Standing against the wall, trying to appear unobtrusive, Max scanned the crowd for a familiar face but recognized no one. In the middle of the dirt floor an old quilt was spread out with neatly crumpled stacks of ones, five, tens, and twenties. Next to them was a modest pile of turquoise and silver jewelry and two Ganado red rugs.

One by one, in no particular order, the people stood up and spoke for several minutes, like an all-night fast and testimony meeting in Navajo, the family members giving thanks to those who had come, the others offering condolences and mini-eulogies for the deceased. There were yawns, muted coughs, infant cries, occasional sobs, but mostly silence. Every so often someone sneaked up front and added a few bills to the stacks. Modestly, humbly, almost embarrassed, going up in a crouching walk, the way people do at the movies when they have to walk in front of the projector. But good-sized stacks. There must have been a thousand dollars cash, plus the rugs and the jewelry. All that the Friday before the G.A. checks came in, when most of them didn’t have gas money to get home. No, in that way they have it over us. Death is a community experience — not just casseroles and Hallmark cards. The bell really tolls for everyone out here.

Max stood and ran water over the brushes, reflecting on those somber faces in the crowd. To outsiders—him too, when he’d first come to the Rez—they appeared grim, even hostile. A bitter, grave, humorless people. But that was their facade, like our white-man counter, the Ultra-Brite smile. We rarely hang around long enough to see the flip-side. The simple, the happy, the content. . . .

Max recalled the summer evening he drove ten miles down the bumpy dirt road to visit Charley Sam. Just behind the shade-house, in a twenty-foot square of newly placed cinderblocks, twelve kids of all ages were chasing around, laughing, playing tag. No one was excluded. A little boy in sagging Pampers plodded alongside teenaged tomboys in bluejeans. Brother Sam came outside to greet Max.

“Ya’at’eeh, Brother Max!” he greeted cheerfully.

Small talk.

“Gotta start workin’,” he said.

“Where at?”

“Pin-yon.”

“That’s a long way to commute.”

“Yeah. I guess I’ll wait for the Fourth of July.”

“What’s happening on the Fourth?”

“I don’t know. Maybe have a family get-together.”

Slow and easy.

Teepees and peyote paraphernalia. But you can’t deny those twelve kids. Relatives, relatives of relatives . . . And the kids were laughing and happy and Sister Sam didn’t chew them out for playing in the dirt or Brother Sam for climbing all over the pick-up. Without guilt, Father. Or .. . well, just without. And walking back to the car, remembering how I used to wince every time my kids even breathed on the Fairmont when it was new . . . No sounds here except kids laughing and the baaing of sheep and just plain flat beautiful solitary land, vast and empty, and so quiet and peaceful with the mesa on fire one minute, deep ocean purple the next. All those colors seeping in and out as if You were backstage with a giant projector showing off Your repertoire of lights . . . And walking back, I sensed no bitterness, no frustration in their lives. Not like me, secretly gnashing my teeth, where ambition and aspiration and conscience are guilt, win or lose.

Say, these brushes. . . . You stick them under the tap and the paint just keeps running. I don’t know where it all comes from—all that paint hidden up inside one tiny brush—but it just keeps running and running and running.

When he started the last phase of clean-up, tugging the steel comb through the brushes, he heard a dainty percussion, like tiny candies striking glass. In the cramped, windowless room, Max listened hopefully. He dropped the brush and comb and stumbled out the door and down the hall into the foyer. Flicking on the light, he saw it, clear, slow, syrupy, crawling like sweat down the double glass doors. He bolted out and into the humid night.

Rain was falling but faintly, like clipped hairs. Max looked pleadingly up at the starless, blackened sky. Lightning flashed to the north, followed by rumbling growing gradually, culminating in a loud, cannonballing blast. Another flash to the south, followed by more rumbling, more thunder, more lightning, over and over, alternating, lightning and thunder, flash and boom, like opposing armies exchanging heavy fire.

Max smiled. Lightning began running wild on the horizons, roller coaster ing up and down, a Chinese dragon celebrating the New Year. Max peeled off his t-shirt and dropped his garments to his waist. The faint drops tickling his flesh, he waited for the flood to fall. The thunder boomed and the lightning flashed, but the faint falling hairs thinned rather than thickened.

Max lowered his head with a grin of self-mockery. Within the cannon balling commotion, he heard a weird metallic twang, like a ricocheting bullet, coming from the hill. A savage bolt of lightning reached down and struck within a hundred feet of the churchhouse, skeletonizing everything in sight. Another bolt, just as bright, struck even closer. Then more, one after another, in rapid succession, igniting land and sky as if with white fire, electrifying everything metal.

Max backed against the churchhouse, crouching under the eaves. With each lightning flash, the water tank glowed and shimmied like a UFO; the telephone wires turned into electric eels. The sky was a Fourth of July spectacular in silver and white — dazzling, intimidating — God’s Almighty signature streaking back and forth across the sky. But dry.

Max hitched up his garments, put on his t-shirt, and was about to head back inside when he saw—or thought he saw—yes: x-rayed in a lightning flash, shawled and stoop-shouldered, an old woman. The elusive saani who had wished him peace, beauty, and harmony. He called out “Shimasanil” but his cry was smothered in thunder. In the next strobic flash, she was gone.

Max returned to the janitor’s closet and resumed tugging the steel comb through the brush, his hands still shaky from the wild lights, the sticky heat, his hallucination . . . Or revelation? You keep sending me clues, messengers. Am I too out of touch, or is this a tease? When had he first seen the woman? Like a flash from the wild light show outside, he remembered: his first year, tracting with the missionaries one winter afternoon, beating a snowy path from hogan to hogan. Crossing the frozen wash, Elder Richfield was “moved by the Spirit” to make a detour. A half mile later they found her, sitting in the bottom of an arroyo, bending forward and back, wincing, whimpering softly. Richfield, the senior companion, spoke to her in Navajo; then to Max.

‘”She was herding sheep and slipped on a rock. She hurt her leg. Can’t walk.”

Max and the two young elders rigged up a stretcher Boy Scout-style and hiked her out of the arroyo to their pick-up and drove her to the PHS Clinic. She said nothing, just sat there wincing, rubbing her pleated skirt up and down her calf. From the clinic she was sent by ambulance to the Indian Hospital in Gallup.

The following Sunday Richfield called him aside. “Remember that old saani? Elder Wheeler and I were in town yesterday, so we stopped by the hospital to see how she was doing . . . Broken leg . . . Yeah. She said after her fall she sat there all night in the arroyo waiting to die. Cold, hungry. Coyotes howling not too far off. She thought she was a goner.”

Then just before dawn, an apparition: a woman with her face, but wearing the buckskin and leggings of two centuries ago. “Do not worry, my granddaughter. Two young men will soon come to help you. . . .”

The elders. I was the odd-man out.

At the hospital the old woman, her leg in a cast, looked at Elder Richfield: “I want to be baptized.”

Richfield, caught off guard, stammered, “Hagoshii . . . that’s good that you want to be baptized . . . but the discussions . . . you haven’t heard the discussions—”

The old woman pointed with her lips to a picture on the wall, The Last Supper: “Last night, that man in the middle there, he told me I should be baptized. He told me you would come.”

I remember now. Nanibaa Yoe. She was baptized. Then we never saw her again. Not at church. But that simple, unpremeditated faith. Like Sister Watchman. Refuting a tumor in the name of the priesthood! The audacity! But that’s the way they are, Father. And it was maybe my own cynicism, coming so puffed up with grand visions, big plans — a ward in two years! A stake in three! Like the other anglos out here: our “mission” among the Lamanites! White Mormondom’s burden: save the Indians! But we get jaded, skeptical. Too many failures, contradictions. We lose steam and poop out.

Sucking in a deep breath, Max shook the last brush dry, hung it on the rack, and switched off the light. For a moment he considered checking all of the doors, but it was already past midnight, and who else had been in the churchhouse during the week? So he turned off the lights in the hall and the gym, and without ceremony or sentimentality, locked up the churchhouse for the last time.

Half the sky was clear and a cool wind was blowing from the south. The sensual, pre-rain fragrance, stronger than ever, perked him up like smelling salts. Still, walking home, Max felt no more relieved than he had nineteen hours ago, at sun-up, or a week or a year or. .. .

As he crossed the trailer compound a big German shepherd raced out with fangs flashing as if he meant business.

“Caesar!” Max yelled, but the animal took a nip at him anyway. “Damn you, Caesar! It’s me—Max! Jeez! How long does it take? It’s only been—” He stopped in mid-sentence, not for fear of the dog but of his own voice, the two painful words echoing in his brain. Ten years, Father, and I still don’t know them or understand them. They’re always surprising me.

Walking on, he recalled one night leaving the Deswoods’ scrap lumber shack, the strange figure peering out from behind a rusty skeleton of a Chevy, whispering: “Psst! Hey!”

Across the highway, disco music blasting from the trading post and, cast in a sundown silhouette, three men sitting on a knoll passing around a bottle. The figure wobbled toward Max. Levis and a T-shirt, with oily black bangs and an oily brown face and eyes cracked red and his breath reeking so bad even the mosquitoes stayed away. He walked almost smack into Max before stopping, asking in a slow, slurred voice, “I wonder if you can help me?”

“What kind of help?”

“Will you . . . will you pray for me?”

Max, recognizing the more subtle ploy, nodded. “I’d be happy to pray for you.” He was about to add, “Come to church on Sunday — nine o’clock — and I’ll have the whole branch pray for you . . .” but the man had already bowed his head and closed his eyes, waiting, his face a weird blend of drunken remorse.

“Do you want me to pray right now?” Max asked, surprised.

He nodded.

Max lowered his head. “What’s your name?”

Head bowed, eyes closed, he answered softly, “Chester. Chester Deswood.”

“David’s brother?”

He nodded.

They stood uncomfortably close, their faces almost touching, like two Arabs. Max prayed: “Heavenly Father . . . we’re grateful to come before thee this night .. . we ask thee for a special blessing on Chester at this time . . . help him feel better . . . help him eat good foods and take care of himself and obey Thy commandments . . . help this illness pass. … ”

When Max finished, Chester extended his hand. But the whole time, even while praying, I kept waiting for him to pop the question. But he never did. He shook my hand and said thank you, thank you very much, his eyes even redder than before. That was all he wanted, a prayer. And walking back to my car I kept thinking of all the things I could have said—remember, Chester, that you are a spirit child of God, never forget that; always pray to your Heavenly Father, for He loves you and will listen to you and care for you . . . I could have done the only thing that makes me worth my salt, out here or anywhere, brought a little comfort to a troubled soul. But even there I fouled up, too busy thinking how to say no no no, shibeeso ddin. So I muttered a token prayer.