Articles/Essays – Volume 17, No. 2

From Sacred Grove to Sacral Power Structure

In more than 150 years, Mormonism has experienced a series of interrelated and crucial transitions, even transformations. This study de scribes five of these linked transitions as individualism to corporate dynasticism, authoritarian democracy to authoritarian oligarchy, theocracy to bureaucracy, communitarianism to capitalism, and neocracy to gerontocracy.

These changes in Mormonism, headquartered at Salt Lake City, are particularly important to understand in view of the demographic significance of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At present, the LDS population is 5.5 million, and membership is doubling every fifteen years. The LDS Church is the largest religious organization in the states of Utah and Idaho, the second largest in Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Washing ton, and Wyoming, the third largest in Alaska and Montana, the fourth largest in New Mexico, the fifth largest in Colorado, and the fifth largest separate religious organization in the United States as a whole. Even outside the United States itself, Mormon demographics are important: the LDS Church is the fourth largest in Tonga and Samoa, and has growing significance in Latin America and elsewhere.[1]

In June 1830, a Protestant minister of Fayette, New York, observed with alarm the organization and growth of Joseph Smith’s new church within his own parish. After estimating that the “Mormonites” had converted between 5 and 7 percent of the township’s total population in the space of only three months, he found one solace: “Past centuries have also had their religious monstrosities, but where are they now? Where are the sects of Nicolaites, Ebionites, Nasoreans, Montanites, Paulicians, and such others which the Chris tian churches call fables. They have dissolved into the ocean of the past and have been given the stamp of oblivion. The Mormonites, and hopefully soon, will also share that fate.”[2] Reports of Mormonism’s death, to paraphrase Mark Twain, have been greatly exaggerated, but the nature of Mormonism’s change through growth has been underestimated.

One of the earliest transitions centered on the question of individualism. Although the various manuscript accounts of Joseph Smith’s visionary experiences with Deity contain some differences of emphasis and detail, they agree on one essential: the Sacred Grove was not a shared experience—it was solitary, supranatural, and not subject to verification by independent witness or analysis. The Sacred Grove of Joseph Smith’s experience did not contain nor imply a church, a community, and certainly not an ecclesiastical hierarchy.[3] Until 1830, Mormonism was an individual with a vision of himself and his relation ship to God and God’s revelation to him through angels, the Bible, and emerging new scriptures. This was so even though that one individual moved in a circle of other individuals with their own experiences, visions, revelations, and confirmations that had been triggered through personal or vicarious contact with him.

In a narrow sense, that same process continues to the present in Mor monism, but it does so through the structure of a church organization, which did not exist for several years of Mormonism’s gestation period. Joseph Smith said his First Vision occurred in 1820, yet in the 1970s there were no massive sesquicentennial celebrations of that event or of any of the other events of Mor monism during its nonchurch existence, when it was revelation, doctrine, testimony, conversion, priesthood, and saving ordinance, but not structure. By contrast, 1980 witnessed extensive publicity and celebration of the Church’s 150th anniversary.[4] Because structure is a central issue of Mormonism, this paper gives priority to administrative power rather than doctrine and personal conversion.

Although Joseph Smith, Jr., was proclaimed a prophet, seer, and revelator when he organized a new Church of Christ on 6 April 1830 in New York State, the Mormon hierarchy as an institution of leadership can be dated from 8 March 1832, when Joseph Smith ordained two men, Jesse Gause and Sidney Rigdon, to be his counselors in presiding over the Church with its few hundred members.[5] It is this jurisdiction over the whole membership of the Church that distinguishes the Mormon hierarchy from other officers with subordinate jurisdiction who had functioned from the first day of the new Church’s existence. By the mid-1830s these men were termed “General Authorities”; and from 1832 to 1932, a total of 124 men served in that capacity. About 100 more General Authorities have served in the hierarchy since 1932.

By 1835, all of the officers and councils of officers (called “quorums”) existed in the Mormon Church as they have down to the present; but the jurisdiction of Church officers in 1835 was very different from what it is today and, in fact, from what it was when the founding prophet died in 1844. Figure 1 shows the jurisdiction of the Church as described in the revelation of 28 March 1835, known as section 107 in the Utah Doctrine and Covenants. By a process of slow evolution, Joseph Smith gave increasing responsibility and administrative powers to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, until by 1844 the Quorum of the Twelve was de facto the second most powerful body in the Mormon Church after the First Presidency.[6]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1, see PDF below, p. 12]

Because Joseph Smith had provided too many precedents and possible authorities for avenues of succession to his office in the event of his death and because he had not published for the benefit of Church members a clearly stated outline of the order and precedence of presidential succession, there was a succession crisis following his death. For most members of the Church, this crisis was resolved permanently when several thousand Mormons voted on 8 August 1844 to accept the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles as the First Presidency of the Church. For other Latter-day Saints in 1844, the succession crisis was not resolved for as long as sixteen years later; and for still other Mormons of 1844 it was never resolved.[7] Several religious groups today continue to affirm the prophetic mission of Joseph Smith through different avenues of succession. By the time Mormon Church headquarters became Salt Lake City, the Quorum of the Twelve and its administratively autonomous First Presidency had clarified the jurisdictions of the hierarchy as shown in Figure 2.

From the 1820s to the 1830s, Mormonism moved from being a collection of individuals whose equally valid personal revelations revolved around Joseph Smith’s theophany to being a church membership with vaguely defined obligations to Joseph Smith as president and to his evolving hierarchy. It became necessary to establish a working relationship between the converted individual of Mormonism and the corporate structure of Mormonism. An immediate problem in the new Church was that individuals who had supranatural, revelatory experiences of their own could not see that these were in any way inferior to the theophanies and revelations of Joseph Smith. This view posed no threat to pre-1830 Mormonism, but it invited disaster to the newly restored Church of Christ in which Joseph Smith was designated by revelation on 6 April 1830 as “a [not “the”] seer, a translator, [and] a prophet” (D&C 21:1; italics added).

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 2, see PDF below, p. 13]

Joseph Smith responded to the problem by dictating a revelation in February 1831 in which the Lord stated that only Joseph Smith and his successors could give commandments and revelations to the Church (D&C 43). A countervailing principle, however, had already been established in a revelation through Joseph Smith that “all things shall be done by common consent in the church, by much prayer and faith” (D&C 26:2). Religious autocracy in Mormonism was moderated by the requirement for the individual Mormon to obtain personal confirmation and to participate in group voting to accept or reject the propositions of the hierarchy.[8]

In the nineteenth century when Mormonism was most compact and cohesive as both church and society, the individual had tremendous leverage in challenging the decisions of the Mormon hierarchy, even at the most crucial administrative levels. In 1843, Joseph Smith instructed an assembled conference of thousands of Church members that he wanted them to vote against the continued presence of Sidney Rigdon as a counselor in the First Presidency. Instead, the assembled multitude voted to retain Rigdon in his position.[9]

Joseph F. Smith as president of the Church in 1904, publicly informed non-Mormons that during the previous fifty years, Utah local members of the Church had frequently set aside administrative decisions of the General Authorities through the law of common consent. In one case, he said, President Young asked the ward membership to release their aging bishop, Jacob Weiler, and sustain a new bishop, “but when the proposition was made to the people they voted it down; they preferred their old, trusted, and tried bishop, and voted down the proposition [presented to them by Brigham Young] to remove him and put in a new one.” In another case, President Young presented a man to be the new president of a stake: “When his name was presented to the conference they voted him down; they rejected him; and of course that is a matter that pertains to the presidency of the church. They preside over all these matters, and it is their duty to install presidents of stakes. But President Young’s proposition was voted down. The people were consulted as to their choice for president, and another man was chosen and sustained as the president of the stake, and not the one who was proposed by President Young.” Similar examples occurred at other stake conferences of the Church presided over by members of the Quorum of the Twelve.[10] Even with a matter of such dramatic importance as the 1890 Manifesto prohibiting the continued practice of polygamy, the members of the Church demonstrated amazing public resistance to the propositions of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Con temporary diaries indicate that most of the thousands of persons in the Salt Lake Tabernacle refused to vote for or against the Manifesto when it was presented, and therefore the document was “sustained unanimously” only by the minority of the audience that voted at all.[11] This independence of the membership of the Church in regard to the dictates of the Church leaders was encouraged by the strong-willed and often-embattled President of the Church Brigham Young:

Some may say, “Brethren, you who lead the Church, we have all confidence in you, we are not in the least afraid but what everything will go right under your superintendence; all the business matters will be transacted right; and if brother Brigham is satisfied with it, I am.” I do not wish any Latter-day Saint in this world, nor in heaven, to be satisfied with anything I do, unless the Spirit of the Lord Jesus Christ, the spirit of revelation, makes them satisfied.[12]

The popular vote against new stake presidents and bishops chosen previously by council meetings in Salt Lake City was apparently the reason the First Presidency and Twelve addressed the question: “Shall the Priesthood nominate and the people accept, or shall the people nominate?” They concluded, “It is quite proper for the brethren before making appointments to consult with the local authorities and be sure to select men for position whom the people will be glad to sustain.” George Q. Cannon, first counselor in the First Presidency, added, “If we try to force matters contrary to their will, a rebellion is apt to ensue. We should never over-reach our influence, or disaster will result.”[13] In practice, this was accomplished by the visiting apostles convening a special priesthood meeting at which those present voted in secret ballot for the man they wanted as bishop or stake president, and the apostles typically selected the man who received the most votes.[14]

As the Mormon Church membership became more diffuse in the twentieth century, less cohesive geographically, and more significant internationally, the potentials for this limited democracy within authoritarian Mormonism seemed awesomely centrifugal, and there was a gradual diminishing of emphasis upon individual prerogative while authoritarianism increased. Nevertheless, for the first seven decades of the twentieth century, the three highest echelons of the Mormon hierarchy contained prominent spokesmen for the importance of in dividual prerogative. In the early 1900s, B. H. Roberts of the First Council of Seventy publicly criticized his ecclesiastical superiors; and from 1921 to 1953, the Quorum of the Twelve’s most noted “intellectual” was John A. Widtsoe, who could publish a series of meditations on gospel questions that included the following statement about sustaining votes: “. . . but the men and women thus nominated must be confirmed by the people. Without such confirmation the nominees cannot act, and other choices must be made, as has occasionally happened. . . . Every person may vote freely, for or against a name; and should do so according to his convictions. The voting is not a perfunctory act, but one of great importance.”[15] Moreover, Hugh B. Brown, in the last year of his service as a counselor in the First Presidency, told the youth of the Church at Brigham Young University, “We are not so much concerned whether your thoughts are orthodox or heterodox as we are that you shall have thoughts,” and on another occasion defined Church loyalty in this manner: “While all members should respect, support, and heed the teachings of the Authorities of the Church, no one should accept a statement and base his testimony upon it, no matter who makes it, until he has, under mature examination, found it to be true and worthwhile; then his logical deductions may be confirmed by the spirit of revelation to his spirit because real conversion must come from within.”[16]

After 1969, the office of the Church president was rilled, first by doctrinaire theologian Joseph Fielding Smith, and then by rigorous administrator Harold B. Lee. Their brief presidential terms seemed to coincide with a rapid end to the institutional support previously expressed about the need for both individualism and authority.

With momentum gradually building to a new orthodoxy, members of the Mormon hierarchy began instructing the Latter-day Saints publicly that “sustaining votes” indicated whether the individual was accepting the Lord’s will and reflected upon the person casting the negative vote rather than upon the person being voted against. For example, in April Conference 1972, a General Authority explained: “To sustain is to make the action binding on ourselves and to commit ourselves to support those people whom we have sustained. . . . If for any reason we have a difficult time sustaining those in office, then we are to go to our local priesthood leaders and discuss the issue with them and seek their help.” Two years later, an article by a Brigham Young University professor of religion in an official Church magazine explained that a person needs help who has voted against an officer who is presented for sustaining vote because “he has placed himself in opposition to those who have been called to positions of responsibility in the Lord’s Church.”[17] Despite their acknowledged preference for willing obedience, the earlier authorities sought to maintain a balance between the prerogatives of freedom for the individual and the necessities of obedience for the institution. Recent General Authorities have shifted the weight of emphasis from one side of the balance to the other.[18]

In this respect, Mormonism can be seen to have changed from an authoritarian democracy to an authoritarian oligarchy. In the earlier years of Mor monism, an overt tension, officially encouraged by the hierarchy, kept a balance between individual prerogative and authoritarian decree. In contemporary Mormonism, the trend is definitely toward an insistence upon unexamined obedience, with the assumption that any tension will be felt only by the marginal member of the Church. This transition is not peculiar to Mormonism, but is a manifestation of the “Iron Law of Oligarchy” as defined by German sociologist Robert Michels in 1911. No matter how democratic in philosophy a movement may be and no matter how idealistic its leaders may be, Michels observed:

. . . every system of leadership is incompatible with the most essential postulates of democracy. . . . It is organization which gives birth to the dominion of the elected over the electors, of the mandatories over the mandators, of the delegates over the delegators. Who says organization, says oligarchy. . . . Large-scale organizations give their officers a near monopoly of power.[19]

Because the Mormon Church was organized and authoritarian from the day of its inception in 1830, no one should be surprised at the dissipation of Mormon ism’s democratic undercurrents.

Other tensions developed within the central oligarchy of Mormonism, the five presiding quorums of the Church, which have been designated here as the Mormon hierarchy. The revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants established broad areas of jurisdiction for these bodies of General Authorities, yet inevitable jurisdictional conflicts have surfaced periodically in the last 150 years. These conflicts did not constitute apostasy, but instead involved administrative tensions between faithful and devoted General Authorities.[20]

A persistent area of tension, redefinition, and adjustment has involved the financial role of the First Presidency and the financial role of the Presiding Bishopric of the Church. Every few years from the 1830s nearly to the present, the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve have concluded that the Presiding Bishopric was administering things that were the financial prerogative of the First Presidency. There would be an adjustment and redefinition circumscribing the financial responsibilities of the Presiding Bishopric; and then, in the next few years or decades by a slow process of accretion, the Presiding Bishopric’s primary mission of “temporal” administration overlapped and some times seemed to subordinate the financial role of the First Presidency to the extent that another consultation-adjustment-redefinition occurred. The cycle has been a persistent one.

Another area of tension centered on the size and implications of jurisdiction in the office of Presiding Patriarch. The Presiding Patriarch was the only quorum of the hierarchy consisting of a single person, and the prestige of that office was heightened by the fact that the Patriarch to the Church was sustained as a prophet, seer, and revelator, as were the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. The Presidency and Quorum during much of the nineteenth century were haunted by the memory of William Smith, the Prophet’s last surviving brother, who insisted almost as soon as he was ordained Presiding Patriarch in 1845 that the office made him President of the Church in the absence of an organized First Presidency. Whenever a Patriarch to the Church after 1845 tried to magnify his presiding office, the Twelve and Presidency recoiled in apprehension that a vigorous Patriarch to the Church might wield too much authority and dare to challenge the automatic apostolic suc cession that has existed since 1844. But when individual Patriarchs to the Church after 1845 seemed to lack administrative vigor, the Quorum and Presidency criticized them for not magnifying their office. Essentially the situation was unresolvable, until 1979 when the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles announced that the existence of organized stakes, each with a stake patriarch, throughout most of the areas of the world where Mormons resided, removed the necessity for the office of the Patriarch to the entire Church. When the incumbent Patriarch to the Church was retired and given emeritus status without the appointment of a successor, the hierarchy resolved more than 130 years of tension.

The situation of the First Quorum of the Seventy was similar but at the opposite end of the size spectrum. At its full complement of seventy men, the Quorum of Seventy was almost five times larger than the combined size of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the Doctrine and Covenants specified (without clarification) that the full Quorum of Seventy is “equal in authority to that of the Twelve special witnesses or Apostles just named” (D&C 107:26). This posed disturbing possibilities when Joseph Smith’s death removed the apex of the hierarchy—the First Presidency—and left the Quorum of the Twelve and the full Quorum of Seventy. Even after the conference of August 1844 accepted the Quorum of Twelve as the acting Presidency of the Church, the Apostles seemed dwarfed administratively by the First Quorum of Seventy which was six times larger than the Quorum of Twelve and which had a revealed, but unexplained, equivalence of authority with the Twelve. In September 1844 Brigham Young simply vacated the First Quorum of Seventy by removing its subordinate sixty-three members to serve as presidents of sixty-three local quorums of Seventy. This action shifted the ambiguity of D&C 107:26 from a practical administrative problem to merely a theoretical one, and Brigham Young’s act amounted to removing a possible rival to the supremacy of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

This left the first seven presidents of the First Quorum to serve in the anomalous position of the First Council of Seventy, without a quorum in existence over which they were the technical presidents. In the 1880s, the 1920s, the 1930s, and the 1940s, the First Council of Seventy, asked the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve to organize the full First Quorum of Seventy so that the First Council would have its own quorum as provided by the revelations. The Presidency and Quorum refused because of the unknown potentials of administrative difficulties in restoring to existence a mammoth body of administrators who might be led to challenge the prerogatives of administrative supremacy that have always existed in the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve.[21]

Only the enormous growth of Church population in the 1960s and 1970s made it seem necessary to increase the number of General Authorities by begin ning to fill up the First Quorum of Seventy in October 1975. The First Presi dency and Quorum of the Twelve adopted four policies, however, as insurance against an unwanted assertiveness of the First Quorum of Seventy. In October 1976, they began rotating the seven presidents of the Quorum of Seventy back into the general membership, and in September 1978 they established an emeritus status for General Authorities by retiring seven older members of the Seventy (six of whom were younger than some members of the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve at the time). In April 1984, the First Presidency also announced that new appointees to the Quorum of Seventy would serve for less than ten-year periods, at the same time affirming that calls to the Quorum of Twelve were for life tenure. These unprecedented alterations have made it virtually impossible for men within the First Quorum of Seventy to develop the seniority and continuity of leadership necessary to project the semi-autonomy implied in the Doctrine and Covenants and traditionally feared by the upper most echelons. The fourth policy has been implemented at the local level and further diminishes the ecclesiastical status of the First Quorum of Seventy: contrary to 150 years of precedent, Church headquarters has now instructed local leaders that the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve are the only echelons of the General Authorities to be presented for sustaining vote of the membership of the Church in local conferences.[22]

The final tension within the Mormon hierarchy is the most significant be cause it exists between the two policy-making bodies of the Church: the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Since 1847, the First Presidency has always been created by the Quorum of the Twelve, and there fore the Presidency has conducted its direction of the Church with the advice and consent of the Twelve. Difficulties have arisen when apostles have concluded that the First Presidency or the President of the Church himself has acted too independently of that advice, consent, or even knowledge of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Although these administrative tensions between the organized First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles have often surfaced and been resolved in the space of a single meeting, day, week, or month, there have been occasions of prolonged, unresolved tensions. For example, the three periods in which the Quorum of the Twelve allowed the First Presidency to go unorganized (1844-47, 1877-80, 1887-89) resulted from the unwillingness of at least a portion of the apostles to organize a First Presidency they feared would ignore the Quorum of the Twelve in the decision-making process. In one case, there was a ten-year administrative impasse between the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, from 1932 to 1942, on the question of the man to be appointed as Patriarch to the Church. The Quorum of the Twelve had voted to recommend one man for the office and the First Presidency had recommended another. Neither side was willing to retreat from its position for a decade, and the office of Presiding Patriarch remained vacant until the Quorum of the Twelve finally relented.

All of these tensions are manifestations of a universal inability for humans to exercise power of any kind without disruptions of personality or jurisdiction. A shared testimony, devotion, and love greatly reduce and moderate, but do not eliminate, such tensions within the general quorums of the LDS Church.

As Mormonism changed from an individualistic movement to an increasingly organized church, the Mormon Church manifested in the composition of its General Authorities features of dynasticism and corporation. In the sense of dynasticism, family interrelationships became a social subsystem of the Mormon hierarchy by the mid-1830s. In the corporate sense, men were advanced as LDS General Authorities in conscious representation of significant ethnic populations within Church membership.

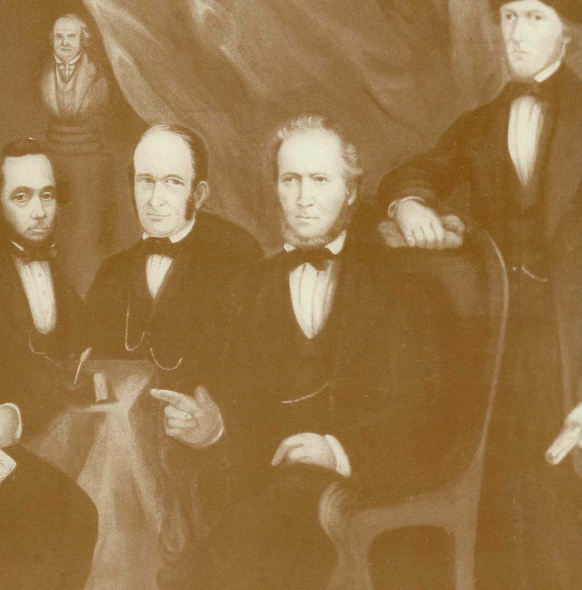

At the most obvious, the importance of family interrelationships can be seen in the fact that 23.6 percent of the men appointed to the Mormon hierarchy between 1832 and 1932 were sons of other General Authorities. Revelations dictated by Joseph Smith and subsequent pronouncements by his successors in office have indicated that men have the right (or at least the pre disposition) to preside in the LDS Church by virtue of their familial lineage.[23] Although only the office of Presiding Patriarch was restricted to patrilineal succession, all other echelons of the Mormon hierarchy demonstrated intricate family interrelationships. Figure 3 shows in italic capitals the names of appointees from one extended family. In the Mormon hierarchy, relationships as distant as fifth and sixth cousin were recognized and honored, and the men often referred to one another as “kinsmen” or “cousins.”[24]

Moreover, General Authorities used marriage to bring into the hierarchical family men who were unrelated by kinship, as well as to reinforce distant cousin relationships. For example, Joseph Smith married in polygamy the sister of his fourth cousin, Apostle Willard Richards, and contracted a similar marriage with the sister of Brigham Young (who was Joseph Smith’s acknowledged sixth cousin). The marriage of children also aligned General Authorities to one another. For example, recent LDS President David O. McKay entered the hierarchy as an apostle in 1906 without being related by kinship or marriage to any other General Authority, yet in 1928 his son married the niece of Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith, who was President McKay’s successor in the presidency.

The historically dynastic character of the Mormon hierarchy is further indicated in Figure 4. Although the degree of kinship penetration was extensive for the entire hierarchy, it is also evident that familial relationships were most extensive within the most powerful echelons: the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. This study has not probed as extensively the familial relationships of the General Authorities since 1932, but it is my hypothesis that the degree of family interrelationships has remained high in the upper two quorums and has diminished greatly in the First Quorum of Seventy for reasons to be discussed later.

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 3 and 4, see PDF below, pp. 21–22]

Surname differences obscure many of the family relationships that exist among recent General Authorities. For example, Marion D. Hanks of the Quorum of Seventy is fourth cousin to both N. Eldon Tanner, formerly of the First Presidency, and to Presiding Bishop Victor L. Brown, who were them selves first cousins. In 1971 Marvin J. Ashton was welcomed into the Quorum of Twelve by his uncle LeGrand Richards. In 1972 Bruce R. McConkie filled the vacancy in the Twelve caused by the death of his father-in-law President Joseph Fielding Smith and by the advancement of Elder McConkie’s first cousin once removed Marion G. Romney to counselor in the First Presidency. In 1981 Neal A. Maxwell filled the vacancy in the Twelve caused when his wife’s first cousin once removed Gordon B. Hinckley became a counselor in the First Presidency. In the First Presidency of recent years, President Harold B. Lee’s first wife was a first cousin once removed of his First Counselor N. Eldon Tanner, and President Spencer W. Kimball’s wife is a first cousin of his First Counselor Marion G. Romney.[25]

Much as a corporate board of directors represents significant minority blocks of stockholders, the appointment of General Authorities to represent significant ethnic populations of the LDS Church has continued from the 1830s to the present. As the American-born Mormons were supplemented by tens of thousands of Latter-day Saints from Canada and Great Britain, twelve Canadian and British General Authorities served from 1837 to 1938, and five from 1960 to the present. In the nineteenth century, the Scandinavians were the second most important ethnic group in Utah; and from 1862 to 1952 there was a Scandinavian seat among the General Authorities. The idea of ethnic representation was conscious as indicated in 1883 when the First Council of Seventy “met with the Twelve in the Council House to try and select a suitable Scandinavian brother to occupy Bro. Van Cott’s place in our council.”[26]

As the population of the international church has accelerated since the 1960s, the newly expanded Quorum of Seventy has become the vehicle for representing diverse ethnic and foreign populations of Mormons, rather than the tight-knit Quorum of the Twelve Apostles which had non-American members from 1838 to 1975. Since that latter year, the following ethnic and non American populations have become represented by appointments to the Quorum of Seventy: the Hawaiians with Adney Y. Komatsu, the French and Belgians with Charles A. Didier, the Navajos with George P. Lee, the Dutch with Jacob dejager, the Germans with F. Enzio Busche, the Japanese with Yoshihiko Kikuchi, the English with Derek A. Cuthbert, the Canadians with Ted E. Brewerton, and the Latin Americans with Angel Abrea.[27]

Of course, the result of this representation of American ethnics and non Americans in the First Quorum of Seventy will be to diminish still further the family interrelatedness of the Seventy. This is being compensated for by also advancing to the Seventy’s Quorum men who are descendants of former Church presidents and apostles (e.g., M. Russell Ballard, who is a grandson of Apostles Hyrum M. Smith and Melvin J. Ballard and a great-grandson of President Joseph F. Smith) or by advancing men whose wives are similarly descended (e.g., G. Homer Durham, whose wife is a daughter of Apostle John A. Widtsoe and a great-granddaughter of Brigham Young).[28]

For nearly fifty years, another obvious characteristic of the Mormon hierarchy was its theocratic nature. Nauvoo, Illinois, became the pattern for Mormon political hegemony, where Joseph Smith was president of the Church, trustee-in-trust for Church finances, almost sole real estate agent, mayor of the city, chief justice of the municipal court, lieutenant general of the militia at Nauvoo (which had under arms only 1,500 fewer men than the entire U.S. army at the time), and who just prior to his death was a candidate for the U.S. presidency. At the same time, other General Authorities constituted more than two-thirds of the Nauvoo City Council. The venomous anti-Mormon rage of Illinois’s older residents is understandable since theocratic Nauvoo was the second largest city in the state and held the balance of power in every state election until the Mormons were driven out.

Once established in Utah, the Mormon hierarchy’s political activity is demonstrated in part by Figure 5 showing General Authority membership in the Utah Territorial Legislature. In the legislature’s powerful upper house, the hierarchy constituted nearly 77 percent of the membership in 1865. Even after the federal government’s dogged attack on Mormon theocracy in the 1880s, the Mormon hierarchy was able to maintain a defiant persistence of public control of politics. This control was mirrored in the territory’s capital, Salt Lake City, and in other areas of political significance to the hierarchy, where individual General Authorities were sent to oversee the political life.[29]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 5, see PDF below, p. 24]

Beyond the obvious presence of the Mormon hierarchy in public office, the General Authorities were essentially able to create politics in their own image through giving instructions to obedient local leaders, who then passed on the word to local voters. Between the organization of Utah as a territory in 1850 and the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, with its influx of a significant non-Mormon minority, the vote against candidates sponsored by the General Authorities was never more than 6 percent: in 1851 there were no contrary votes, in 1864 only .1 percent contrary, and in 1869 only 45 total votes against Church candidates out of 11,000 cast in the territory.[30]

However, when the Mormon hierarchy was forced in 1890 to surrender the symbol of Mormon distinctiveness—polygamy—that act was a prelude to the acceptance of political pluralism. Shortly before 1890, the First Presidency became convinced that the survival of Mormonism in the United States re quired the good favor of the Republican Party, and therefore (despite official statements of nonpartisanship) the First Presidency encouraged Republican members of the hierarchy to promote the GOP and tried to discourage Democratic members of the hierarchy from being so vocal. The preponderance of Republicans in the hierarchy is shown in Figure 6. These trends continued to the present, but often alienated those General Authorities and rank-and-file Mormons who campaigned and voted in defiance of subtle or open pressures of the Mormon hierarchy along particular political lines.[31]

Contemporary with the transitions in Mormon theocracy were economic developments that represented long tensions between communitarianism and capitalism within Mormonism and within its hierarchy. Although it is generally recognized that Joseph Smith’s revelations commanded economic equality among the Latter-day Saints (epitomized in the United Order of Enoch and the Law of Consecration), it is less well known that other revelations indicated that God was willing for his Church leaders to be supported in their ministry and that there was divine authorization for these leaders to acquire and enjoy material wealth. (D&C 70:15-18) The General Authorities them selves felt the tension between these two imperatives, but the resolution with regard to the hierarchy’s personal wealth tended more to the disparities of capitalism than the equalities of communitarianism (Figure 7). Within the hierarchy itself there were great differences of economic wealth of the echelons (Figure 8).

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 6, 7, and 8, see PDF below, pp. 25–27]

Wealth did not come automatically to the General Authorities by virtue of their position; and in fact it can be demonstrated that in the nineteenth century, the rate of economic growth for a new appointee tended to stagnate or even decline during the first years of service in the Mormon hierarchy. Nevertheless, a man’s tenure as a General Authority increased his potential for wealth, particularly if he was given access to the institutional outlets of the Church for corporate business leadership (Figures 9 and 10). Wealth tended to correspond to the echelon of the hierarchy in which the man served but was also influenced by the talents and personal inclinations of the individual.[32]

As the Mormon hierarchy’s political power was eroded by the U.S. government’s campaign against Mormon theocracy, the hierarchy successfully and ironically retained its hegemony by adopting America’s free enterprise system with a vengeance. When the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act was about to dis incorporate the LDS Church and seize its assets, the President of the Church gave the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve carte blanche authority to engage in business enterprises. The Mormon hierarchy had been engaged in business enterprises since the days of Joseph Smith, but now the extent of this activity eclipsed all former efforts.[33]

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 9 and 10, see PDF below, p. 28]

Although the hierarchy was briefly involved in two banking institutions in 1837, from 1871 to 1932 General Authorities served as officers and directors of at least thirty-four banks and nearly forty other investment and mortgage companies. The hierarchy became involved in a utility company as early as 1845 but from 1872 to 1932 governed twenty-five utility companies. From the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in Utah in 1869 until 1932, General Authorities served as officers and directors of forty-six railroad companies. From the 1870s to 1932, the hierarchy directed the business affairs of eighty-five mining companies, most of which were involved in gold and silver mining. The Church inaugurated its own short-lived insurance company in 1871, and the hierarchy continued to serve eight insurance companies as officers and directors between 1886 and 1932.

Included within the diverse business interests of the Mormon hierarchy were newspapers, books, radio broadcast, telephone, telegraph, construction, brick manufacturing, dairy products, amusement parks, film companies, cemeteries and mortuaries, garment industry, hotels and apartments, irrigation and agricultural concerns, livestock, lumber, iron and steel production, manufacturing and merchandising, laundries, ice storage, warehouses, jewelry retailing, and real estate.

Many of these business enterprises were ill-founded and ephemeral, but others continued for decades, even to the present. Moreover, the LDS Church as an institution sometimes held strong minority stock or even majority stock in companies in which the General Authorities themselves were not represented in directorships or management.

The Mormon hierarchy’s commitment to free enterprise and capitalism, in the twentieth century in particular, preserved the hierarchy’s regional hegemony within the Great Basin of the American West, but it had far more important consequences for the Church as a whole. The commitment to religious capitalism removed Mormonism from being a pariah in America and enabled the Mormon Church to command respect and wield influence in the terms that Americans always have understood and admired. Mormons were no longer regarded as repulsive zealots but as the capitalists next door. The growth of Mormonism as an inward-directed community of communitarian ideals horrified nineteenth-century Americans and resulted in hostile legislation, but the hand-in-hand financial and population growth of the LDS Church as a world wide institution intrigues twentieth-century Americans and has resulted in (often laudatory) articles in Reader’s Digest, Fortune, New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and Wall Street Journal.

The concommitant financial and population growth of the LDS Church gave rise to the transformation of Mormonism from theocracy to bureaucracy. This was first manifested at the turn of the century when the General Authorities became the mainstays of the general boards that governed the various auxiliaries of the Church, and then headed various committees to oversee a welter of administrative functions and activities. Within several decades, the numbers of large committees and general boards had so increased that the General Authorities could no longer provide a significant portion of the membership of each one but were only represented as the most prestigious and powerful members of such boards and committees.

By the time the LDS Church completed its twenty-six-story administration building in Salt Lake City in 1972, the bureaucracy of the Church had become so large that there were too many major departments for each of the General Authorities to govern directly. In addition, there was a mitosis of committees and subcommittees, each of which was of interest to a hierarchy beginning to realize that the geometric population growth of the Church was reflected in a geometric growth of the bureaucracy. Now, the hierarchy would have to run to keep abreast of important developments that the momentum of the bureaucracy was creating.

The recent efforts of the hierarchy to maintain its formerly tight control over the administration of the Church and the Church bureaucracy have been directly related to the previously discussed emphasis on unquestioning rank and-file obedience to Church directives. All these manifestations derive from the same source: an inherent fear of the centrifugal tendencies of enormous Church growth.

Less than two decades after World War II, two members of the First Presidency expressed deep concern about the effects of growth on the hierarchy. J. Reuben Clark, Jr., a counselor in the First Presidency for more than twenty eight years, predicted that the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve would increasingly have to make decisions about matters in which they had little or no training and experience and would therefore depend upon technically trained and experienced bureaucrats. The result, he feared, would be abdication by necessity of the hierarchy’s decision-making in many areas in which technocrats would virtually make decisions that the General Authorities themselves could make only as counseled by the technocrats.[34]

David O. McKay, as president of the Church in the 1960s, believed that even those committees and departments of the Church bureaucracy presided over by General Authorities tended to diminish the importance of quorum decisions by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. “Be careful that you do not take away from the constituted authority of the Church the divine right by ordination and by setting apart and leave that to some committee,” President McKay warned the apostles. Then he added, “If we do that we will be running this Church by Committees, just as the Government has been running the country by Committees, and as it is being run now by Committees. You are the constituted Authority.”[35]

A few current statistics indicate the extent to which the concerns of Presidents McKay and Clark may apply today. The General Church Offices Tele phone Directory, 1984 lists 2,971 employees in twenty-two departments.[36] Thus, excluding the paid employees of the regional arms of these departments and excluding the specialized paid-bureaucracies of Church functions (e.g., Brigham Young University), the LDS Church central bureaucracy at Salt Lake City has one employee for every 1,834 Latter-day Saints throughout the world. By contrast, the U.S. Federal Government statistics show that in the greater Washington, D.C., area alone there is one federal bureaucrat for every 726 persons of the total U.S. population, and that the number of federal white collar workers nationally is one federal bureaucrat per 108 persons of the total U.S. population.[37] But, unlike the federal government, the LDS Church functions primarily through the unpaid services of a lay ministry of Church administrators (general, regional, and local). By adding the number of these unpaid Church administrators to the number of employees in the central Church bureaucracy, there is a ratio of one LDS Church bureaucrat/administrative officer per each 58 Latter-day Saints throughout the world.[38] The value judgment one attaches to these comparative data depends upon one’s point of view, but the existence of a large bureaucracy in the LDS Church is one of the facts of Mor monism’s present and future.

Nearly all of the transitions of Mormonism discussed up to now relate to a final transition: the transformation of Mormonism from a neocracy to a gerontocracy—from the rule of youthful as well as inexperienced leaders to the rule of leaders who are of advanced age and long administrative experience.

This transformation of Mormonism at one level is obvious. At his death in 1844, Joseph Smith was thirty-eight years old, after leading the Church for fourteen years. No president of the LDS Church in this century has been younger than sixty-two. Joseph Fielding Smith was ninety-three years old when he began his presidential service of two-and-a-half years in 1970, and Harold B. Lee was seventy-three years old at the beginning of his nearly eighteen-month presidency in 1972. President Spencer W. Kimball in 1984 is eighty-nine years old. The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had a mean age of about 28.5 years when Joseph Smith first ordained the men in 1835. Despite the death of two apostles, one age ninety-six and the other age eighty-three, the mean age of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles was 66.9 years in January 1984. The administrative realities of the age factor in the Mormon hierarchy are indicated by the opening sentence of Newsweek’s recent article about a very different leadership group: “Only in a gerontocracy could it be said of a leader of 69 that he died young.”[39]

Because General Authorities have had life tenure throughout most of the history of the LDS Church, it was inevitable that even the twenty-year-olds in the hierarchy would grow old and infirm in Church service. The LDS Church’s nineteenth-century emphasis upon a youthful hierarchy was best expressed by Brigham Young in April 1860 (when the mean age of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was 47.5 years) : “The 12 are getting old now, and let others do the preaching abroad.”[40] Brigham Young and every president of the Church until the death of Joseph F. Smith in 1918 responded to the graying of the hierarchy by choosing men under forty years of age for nearly 66 percent of the new appointments to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. The subject of age and experience versus youth and inexperience was the specific question when a new apostle was chosen in 1859:

O[rson] Pratt—”I would like to know on what principle men are to be selected: whether we are to suggest men of experience who have been tried and proven in many responsible positions, or those who are young, & have not been called to important trusts in the Church, or if any qualifications are needed.”

Pres. Y[oung]—”I will answer your question Bro. Pratt to my own satisfaction. If a man was suggested to me of good natural judgment, possessing no higher qualifications than faithfulness and humility enough to seek to the Lord for all his knowledge and who would trust in him for his strength I would prefer him in preference to the learned and tallented.”[41]

In a period in which the Mormon Church was sending apostles on prolonged proselyting and colonizing missions and in a period of confrontation with government authorities, a continual renewal of the hierarchy with youthful appointees seemed absolutely necessary.

In 1918, Heber J. Grant became president of the Church. As an ardent businessman, he had realized even as a twenty-five-year-old apostle that business success and activity with non-Mormons were the means to win acceptance and protection for the growing Church. Heber J. Grant developed extensive business relations with non-Mormons throughout the nation, and in the process saw the success of the political and social transformation already described. As an apostle, Heber J. Grant tried to counter the negative image of Mor monism by carrying personal letters of recommendation from non-Mormon bankers and other influential businessmen of Salt Lake City, Chicago, San Francisco, and New York; and he later told a general conference of the Church, “There is nothing that so completely rebukes the falsehoods against our people” as the praise given to the LDS Church by non-Mormon millionaires. And President Grant always regarded the high point of his public relations effort as the occasion when he spoke to more than 300 businessmen at the Knife and Fork Club of Kansas City, “which I have been informed is the second greatest dinner club in the United States, the Gridiron of Washing ton standing first.”[42]

The needs of Church leadership had changed; and to Heber J. Grant and his successors in the Presidency, it seemed obvious that the Church needed men seasoned in all fields, but especially in business experience, in the Quorum of the Twelve to insure the continued respect and cooperation of national leaders in the Church’s financial, social, and demographic growth. Such business and administrative experience required greater age. Of the men advanced to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles since 1919, only one has been under forty years old; and even that man, Thomas S. Monson, had extensive experience as a young business leader and Church administrator. Therefore, contrary to a common wisdom, the increasing age of the Mormon hierarchy has not indicated a decline in the vitality of Mormonism but instead has reflected a trans formation of the goals and methods of Church leadership.

Nevertheless, just as the enormous growth of the Church has brought other changes, it has also made the Mormon hierarchy acutely concerned with the disadvantages in a gerontocracy of even capable men. The elderly presidents of the Church have chosen their counselors from the Quorum of Twelve’s complement of men also in their fifties to seventies. Although the experience of such counselors is invaluable to the Church President, that experience has often been handicapped by physical infirmities. During the 1940s, only J. Reuben Clark of the First Presidency was well enough to conduct business in the First Presidency’s office for months at a time; and for the last five years of his presidency, Heber J. Grant was unable to attend most of the important weekly meetings of the Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve in the temple.[43] In more recent decades, there have been members of the First Presidency whom advancing age has rendered incapable of walking, talking, or seeing. Aside from the deep personal tragedy of such disability coming to men who have unselfishly devoted their lives to Church service, there is the administrative reality that under such conditions the General Authorities are even less able to keep control of the centrifugal tendencies of tremendous Church growth, and therefore they become even more reliant on a bureaucracy of trusted secretaries, administrators, and technocrats.

At the turn of the century, when Church membership was less than 230,000, John W. Taylor startled his fellow apostles with his blunt statement to the Davis (Utah) Stake Conference about the administrative problems involved in the leadership of an eighty-eight-year-old Church president, the oldest to serve up to that time: “He made some remarks which were scarcely proper concerning the mental and physical condition of Pres. Woodruff, who was unable, he said, to do the work of the Church without the help of his counselors, ‘As well might a baby be placed at the head of the Church as Pres. Woodruff without the aid of Presidents Cannon and Smith.’”[44]

Because Spencer W. Kimball and his associates in the hierarchy became aware of the difficulties that faced the LDS Church from the combination of life tenure, gerontocracy, and mounting administrative pressures, in 1978 they instituted a retirement for General Authorities whereby men are given “emeritus” status and can thereby be replaced by relatively younger new General Authorities. Thus far, this retirement approach has been applied only to the lower echelons of the hierarchy. Retirement to emeritus status in the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles involves momentous questions of apostolic succession to the office of President of the Church. An emeritus status in either of those two highest quorums of the Church will indicate that the Mormon hierarchy has concluded that the enormous growth of the Church, which the president of the Church has described as the “greatest problem the Church faces,” requires fundamental changes in the 150-year-old structure of the hierarchy itself.

The Sacred Grove of Joseph Smith’s experience has a serenity that does not exist in a church of increasing growth, institutional proliferation, and funda mental transitions. If we are inside Mormonism looking back, we may yearn for the seeming stability of an earlier generation or an earlier century. If we are outside Mormonism looking in, we may marvel at what appears to be the establishment of a new world religion. Whatever our point of view, we cannot understand what we are presently experiencing or observing of Mormonism without a thoughtful look at the path that has led from the Sacred Grove.

[1] Deseret News 1984 Church Almanac; World Almanac and Book of Facts, 1984, pp. 350-51, 544, 580; Bernard Quinn, et al., Churches and Church Membership in the United States, 1980 (Atlanta: Glenmary Research Center, 1982), pp. 10-11, 13-14, 18-21, 23, 25, 26, 27; Encyclopedia Americana, 1981 ed., 24:180.

[2] D. Michael Quinn, trans., “The First Months of Mormonism: A Contemporary View by Rev. Diedrich Willers,” New York History 54 (July 1973): 331.

[3] For texts of the various recitals of the First Vision by Joseph Smith himself and of early second-hand accounts of it, see Paul R. Cheesman, “An Analysis of the Accounts Relating Joseph Smith’s Early Visions” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1965) ; Dean C. Jessee, “The Early Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” BYU Studies 9 (Spring 1969) : 275-94; Jessee, “How Lovely Was the Morning,” DIALOGUE 6 (Spring 1971) : 87; Milton V. Backman, Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision: The First Vision in Its Historical Context (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971), pp. 155-77; Dean C. Jessee, The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), pp. 5-6, 75-76, 199-200, 213, 666. In addition, scholarly analyses of the significance of the First Vision have appeared in (chronologically) Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History (New York: Knopf, 1945), pp. 21-25; James B. Allen, “The Significance of Joseph Smith’s ‘First Vision’ in Mormon Thought, DIALOGUE 1 (Autumn 1966) : 29-45 ; Wesley P. Walters, “New Light on Mormon Origins From the Palmyra Revival,” DIALOGUE 4 (Spring 1969): 60-81; Richard L. Bushman, “The First Vision Story Revived,” DIALOGUE 4 (Spring 1969): 82-92; James B. Allen, “Eight Contemporary Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision: What Do We Learn From Them?” Improvement Era 73 (April 1970) : 4-13; Brodie, No Man Knows My History, 1971 rev. ed., pp. 405-12; Marvin S. Hill, “Brodie Revisited: A Reappraisal,” DIALOGUE 7 (Winter 1972) : 78-80; Donna Hill, Joseph Smith: The First Mormon (Garden City, N.Y.: Macmillan, 1977), 41-54; Marvin S. Hill, “A Note on Joseph Smith’s First Vision and Its Impact in the Shaping of Early Mormonism,” DIA LOGUE 12 (Spring 1979) : 90-99; Klaus J. Hansen, Mormonism and the American Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1981), 1-44; and Marvin S. Hill, “The First Vision Controversy: A Critique and Reconciliation,” DIALOGUE 15 (Summer 1982): 31-46. None of these interpreters has explicitly stated the interpretation here presented of the First Vision as it relates to the organization of the LDS Church. To acknowledge that there was no provision for an organization of a church in any account of the First Vision counters the hostile interpretations of Brodie and Walters that the First Vision was “evolutionary fantasy” or after-the-fact explanations of Mormonism. Marvin Hill is engaging in anachronistic interpretation, unsupported by the contemporary vision accounts, when he writes, “The vision informed Joseph Smith that none was right and that the true church would have to be re stored” (“A Note,” p. 95). Donna Hill (p. 105) comes closest to my interpretation by stating, “To the converts, Joseph’s Church was not only based upon the Book of Mormon, but the book was its reason for having come into existence.”

[4] For a quick comparison of the relative importance given by Church leaders to the two sesquicentennial occasions, see Improvement Era and Deseret News Church Section for 1970, particularly for April-July 1970, and compare with Deseret News 1981 Church Almanac, pp. 13-41, especially for 27 Oct. 1979, 1 Jan., 10 March, 26-28 March, 3 April, 5-7 April, 13 April, 13 June, 12 July, 19 July, 24 July, 2 Aug. 1980. Also see Ensign and Deseret News Church Section for 1980, particularly for January-July. A similar disparity occurred in the quiet observance of the centennial of the First Vision in 1920 compared to the dramatic publicity and celebrations of the centennial of the organization of the Church in 1930.

[5] D. Michael Quinn, “The Evolution of the Presiding Quorums of the LDS Church,” Journal of Mormon History 1 (1974) : 23-25; Quinn, “Jesse Gause: Joseph Smith’s Little known Counselor,” BYU Studies 23 (Fall 1983).

[6] T. Edgar Lyon, “Nauvoo and the Council of the Twelve,” The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History, F. Mark McKiernan, Alma R. Blair, and Paul M. Edwards, eds. (Lawrence, Kan.: Coronado Press, 1972), pp. 167-205; Quinn, “Evolution,” 26-31; Ronald K. Esplin, “The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership, 1830— 1841” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1981).

[7] D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Succession Crisis of 1844,” BYU Studies 16 (Winter 1976): 187-233; Ronald K. Esplin, “Joseph, Brigham and the Twelve: A Succession of Continuity,” BYU Studies 21 (Summer 1981): 301-41; D. Michael Quinn, “Joseph Smith Ill’s 1844 Blessing and the Mormons of Utah,” DIALOGUE 15 (Summer 1982) : 69-92.

[8] D. Michael Quinn, “Echoes and Foreshadowings: The Distinctiveness of the Mormon Community,” Sunstone 3 (March/April 1978): 13-14.

[9] Joseph Smith, Jr., History of the Church, B. H. Roberts, ed., 7 vols., 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1950), 6:49.

[10] Testimony of President Joseph F. Smith and Apostle Francis M. Lyman in U.S. Senate, Proceedings Before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-07), 1:355, 356, 474.

[11] Melvin Clarence Merrill, ed., Utah Pioneer and Apostle: Marriner Wood Merrill and His Family: Material obtained from the autobiography, diaries, and notes of Marriner Wood Merrill .. . (N. pub.: By the author, 1937), p. 128, diary entry for 6 Oct. 1890; Thomas Broadbent Diary, p. 24, 6 Oct. 1890, in Miscellaneous Diaries and Journals, Volume 10, type script, Harold B. Lee Library, Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

[12] Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool and London: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1855-1886), 3:45.

[13] Abraham H. Cannon, Diary, 1 Oct. 1891, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[14] Ibid., 20 June 1891; Marriner W. Merrill Diary, 23 April 1900.

[15] John A. Widtsoe, Gospel Interpretations: More Evidences and Reconciliations (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1947), pp. 67-68.

[16] B. H. Roberts letter published in Salt Lake Herald, 7 May 1908; Truman G. Madsen, Defender of the Faith: The B. H. Roberts Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), pp. 271— 72; “Pres. Brown Addresses BYU,” Deseret News Church Section, 24 May 1969, p. 13; see Hugh B. Brown, “An Eternal Quest: Freedom of the Mind,” DIALOGUE 17 (Spring 1984): 77-83; Hugh B. Brown, “Testimony,” Relief Society Magazine 56 (Oct. 1969): 724.

[17] Loren C. Dunn, “We Are Called of God,” Ensign 2 (July 1972) : 43; Alma P. Burton, “All in Favor, Please Signify!” Ensign 4 (March 1974): 16.

[18] The Ensign since 1970 contains numerous references by General Authorities to conference addresses as “marching orders.” E.g., Carlos E. Asay, “Look to God and Live,” Ensign 8 (Nov. 1978) : 54. Representative examples of sermons by General Authorities who emphasize the traditional message of obedience to Church authority without the previously traditional emphasis upon the importance of individuality are Spencer W. Kimball, “Listen to the Prophets,” Ensign 8 (May 1978): 76-78; “Pres. Benson Outlines Way to Follow Prophet,” Deseret News Church Section, 1 March 1980, p. 14; N. Eldon Tanner, “The Debate Is Over,” Ensign 9 (Aug. 1979): 2-3.

[19] Robert Michels, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy, Eden and Cedar Paul, trans. (New York: The Free Press, 1972), pp. 364-65, 16.

[20] Unless otherwise noted, this discussion comes from my “Jurisdictional Conflicts in the Mormon Hierarchy, 1832-1932,” seminar paper, Yale University, 1974.

[21] See also William G. Hartley, “The Seventies in the 1880s: Revelations and Reorganizing,” DIALOGUE 16 (Spring 1983): 79-83.

[22] Deseret News 1983 Church Almanac; Deseret News (8 April 1984): A-l. Up until about 1976 the preprinted list of General Authorities to be sustained at ward and stake conferences included all the authorities, but then Church headquarters began sending out pre- printed sheets listing only the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve, with instructions that the other presiding quorums were to be presented simply as “and all other General Authorities as now constituted,” or words to that effect.

[23] D&C 68:21, 86:8, 107:39-52, 113:18; Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 16 Feb. 1847, Historical Department Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter LDS Church Archives) ; John D. Lee, Journals of John D. Lee, 1846- 47 and 1859, Charles Kelly, ed. (Salt Lake City: Western Printing Co., 1938), pp. 79-81; “A Family Meeting in Nauvoo,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 11 (July 1920): 107-8.

[24] D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Hierarchy, 1832-1932: An American Elite” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1976), p. 40.

[25] George S. Tanner, John Tanner and His Family (Salt Lake City: John Tanne r Family Association, 1974), 350-53 ; Doyle L. Green, “Elder Marvin J. Ashton,” Ensign 2 (March 1972): 15; Lucile C. Tate , LeGrand Richards: Beloved Apostle (Salt Lake City: Book craft, 1982), p. 315; Joseph Fielding Smith, Jr., and John J. Stewart, The Life of Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1972), p. 209; L u r a Redd, The Utah Redds and Their Progenitors (Salt Lake City: N. pub., 1973), pp. 483, 522; “Elder Gordon B. Hinckley Called to First Presidency, Elder Neal A. Maxwell to Quorum of Twelve,” Ensign 11 (Sept. 1981) : 72; Hinckley family records; Descendants of Nathan Tanner (Sr.) (Salt Lake City: Nathan Tanne r Family Association, 1968), pp. 75, 78, 316, 434, 465; and Caro line Eyring Miner, Miles Romney and Elizabeth Gaskell Romney and Family (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1978), pp. 163-64, 223-25.

[26] Abraham H. Cannon, Diary, 14 April 1883.

[27] Deseret News 1983 Church Almanac, pp. 81-87, 94-106.

[28] The Descendants of Joseph F. Smith (1838-1918) (Provo: J. Grant Stevenson, 1976), p. 95 ; “Elder G. Home r Durham, ” Ensign 7 (May 1977): 100; “Brigham Young Genealogy,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 11 (July 1920): 132.

[29] Quinn, “The Mormon Hierarchy,” pp. 158-187.

[30] Ronald Collett Jack, “Utah Territorial Politics: 1847-1876” (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1970), pp. 69-70, 99, 101, 104, 106, 108, 110-11, 116-17.

[31] Quinn, “The Mormon Hierarchy,” pp. 228-66.

[32] Ibid., 81-157.

[33] The data presented here on business activity are a brief review of ten years of research that is still in process.

[34] D. Michael Quinn, J. Reuben Clark: The Church Years (Provo, Utah : Brigham Young University Press, 1983), p. 106.

[35] David O. McKay, Diary, 22 Dec. 1960, LDS Church Archives.

[36] In addition to the staff of the five presiding quorums, the departments of the central bureaucracy are Auditing, Budget, Church Educational, Correlation, Curriculum, Finance and Records, Genealogical, Historical, Information Systems, International Mission, Investments, Materials Management, Missionary, Personnel, Physical Facilities, Presiding Bishopric Administrative Services, Presiding Bishopric International Offices, Priesthood, Public Communications, Security, Temple, and Welfare Services. For more information about the LDS bureaucracy, consult James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), pp. 595-608. Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience (New York: Knopf, 1980), pp. 262-94 ; Randall Hatch, “The Mormon Church : Managing the Lord’s Work,” MBA, June 1977, pp. 33-37 ; David J. Whit taker, “An Introduction to Mormon Administrative History,” DIALOGUE 15 (Winter 1982): 14-19; and Dennis L. Lythgoe, “Battling the Bureaucracy: Building a Mormon Chapel, ” DIALOGUE 15 (Winter 1982): 69-78. Th e estimated ratio of bureaucrat-per Latter-day Saint is quite conservative in view of the fact that there are LDS bureaucracies not included in the roster of the General Church Offices: see Whittaker, “Introduction, ” p. 16.

[37] U.S . Bureau of Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1984 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), p. 333, Table 536, “Paid Civilian Employment in the Federal Government, ” excludes employees of the CIA , N S A, and temporary Christ mas help of the U.S. Postal Service. Th e table lists 312,000 whit e collar employees of the Federal government for the greater Washington, D.C., area, and 2,092,000 white collar employees for the entire nation. This compares to the 1980 U . S. population of 226,545,805 (ibid., p . 6) .

[38] The Directory of General Authorities and Officers, 1984, pp. 5-17, lists 56 General Authorities, 12 international area directors, 440 Regional Representatives, and 26 temple presidencies. According to Church headquarters, as of December 1983 total estimated Church membership was 5,450,000 residing in 1,458 stakes of the Church with 9,326 wards and 2,677 branches, and in 178 missions of the Church with 353 districts and 2,007 branches. From the foregoing, I arrived at the conservative estimate of 90,916 Church administrators on the basis of three per mission presidency, four per district (presidency and clerk), three per branch (rather than the ideal of president, two counselors, and clerk), five per ward (bishopric, clerk, and executive secretary), and nineteen per stake (presidency, clerk, executive secretary, twelve high councilmen, and two alternate high councilmen), and three per temple. Any active Latter-day Saint knows that the administrative officers of the above units are more numerous than the numbers I have assigned for this computation.

[39] Newsweek, 20 Feb . 1984, p . 34.

[40] Brigham Young Office Journal, 11 April 1860, LD S Church Archives. The age calculation does not include thirty-three-year-old George Q. Cannon who was appointed an Apostle while on a mission, but was not ordained into the Quorum of Twelve Apostles until after April 1860.

[41] Historian’s Office Journal, 23 October 1859, LD S Church Archives.

[42] April 1927 Conference Report, pp. 6-7 ; October 1934 Conference Report, p. 5 ; April 1921 Conference Report, p. 7.

[43] Quinn, J. Reuben Clark, pp. 83-86, 90-91.

[44] Abraham H. Cannon, Diary, 3 Dec. 1895.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue