Articles/Essays – Volume 17, No. 2

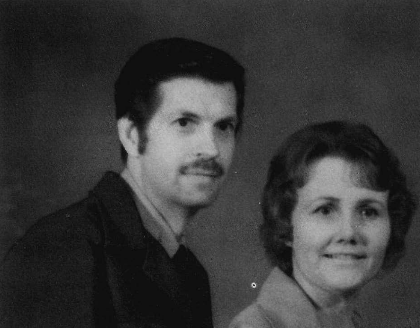

Career Apostates: Reflections on the Works of Jerald and Sandra Tanner

For more than two decades, Jerald and Sandra Tanner have devoted I their lives to exposing and trying to destroy Mormonism. They have succeeded in upsetting Mormons of various persuasions, largely because of their abrasive writing style, a style which is most nearly reminiscent of FBI under cover agents reporting back to J. Edgar Hoover on the terrible continuing threat of the world-wide communist (read: Mormon) conspiracy. Yet the Tanners have been more than simply gadflies; in curious and often indirect ways, their work has also been a factor helping to stimulate serious Mormon historical writing. In addition to publishing many hard-to-find Mormon historical documents, their criticisms have highlighted issues that professional Mormon historians, operating from a very different perspective, have also sought to address.

Despite the importance of the Tanners in these and in other ways, to date I know of no fully convincing scholarly assessment of their activities and significance. Mormon scholars have tended to shy away from public discussion of this controversial topic; anti-Mormon supporters of the Tanners have produced little but uncritical praise; while non-Mormons who know anything about the Tanners have wondered what all the fuss was about.[1] As a non-Mormon scholar who has spent nearly a decade of intensive work in Mormon history without becoming either Mormon or anti-Mormon, I believe that I am in a particularly advantageous position to suggest some new perspectives on the Tanners and to present a balanced analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of their work.[2] On the one hand, I agree with many of the Tanners’ criticisms of the inadequacies of much Mormon historical writing until recently. On the other hand, I am equally critical of the narrowminded Protestant fundamentalism which the Tanners have substituted for the Mormonism that they decry. The reflections which follow seek to raise a few of the many intriguing questions suggested by the life and work of these “career apostates”—individuals who have devoted their lives to the task of trying to destroy a faith in which they once deeply believed.[3]

This article will investigate three main topics. The first has to do with the Tanners’ sense of personal mission. Many people leave Mormonism; few devote their lives to trying to destroy it. What has made the break so profound and deep for the Tanners? A second issue concerns the historical significance of the Tanners. How has their research, publication of documents, and polemicism affected the development of serious Mormon historical studies? A final question concerns how the Tanners’ activities and Mormon reactions may illuminate the development of the Latter-day Saint movement as a whole. Are the Tanners a purely idiosyncratic couple or do they reflect fundamental problems with which the Mormon movement must grapple if it is to become truly a world religion rather than an isolated sect from the Intermountain West?

I shall argue that the Tanners reflect both the strengths and weaknesses of the very Mormonism which, rather paradoxically, they are trying to destroy. Their life and work can tell us much about the dynamics of dissent in exclusivistic religious movements.

I

The distinctiveness and depth of the Tanners’ sense of mission can best be understood by looking initially at the nature and scope of their activities since they first began producing literature critical of Mormonism in 1959. The most widely known apostates in Mormonism or in other religious movements usually make one dramatic break, produce one great expose, or go on one major speaking tour before gradually sinking from sight or moving on to engage in other activities. Whether the break be basically idealistic in motivation, as in the case of a William Law or a T. B. H. Stenhouse, or primarily opportunistic, as in the case of a John C. Bennett or an Ann Eliza Webb, apostates seldom sustain a broadranging and historically valuable career of exposure over many years.[4] Similarly limited is the historical contribution of missionaries from other religious traditions who are devoting their lives to trying to convert Mor mons to another faith. Such missionary anti-Mormons tend to be obviously self-serving, with little regard for history except as a polemical device to try to turn Mormons into Baptists, Methodists, Catholics, or members of some other tradition.

Jerald and Sandra Tanner’s career is more complex than either the typical apostate or anti-Mormon patterns. Not only have they been unusually persistent and dedicated, producing a continuing stream of documents and polemical pieces, but the caliber of their writing has in recent years been higher than that typically found in this literature. The sheer volume of their writing is impressive. A recent bibliography which Scott Faulring prepared of their publications from 1959 through 1982 lists more than 200 items. These range from Jerald Tanner’s first one-page broadside, Does the Book of Mormon Teach Racial Prejudice?, to their massive study, Mormonism –— Shadow or Reality?, with more than 600 closely argued pages. Reprints of Mormon historical and religious writings, important manuscripts, and anti-Mormon exposes comprise forty-four of their publications. And forty-nine of their items are polemical pieces of twenty pages or more which debate virtually every significant topic in Mormonism which has surfaced during the past two decades.[5] The Tanners were productive during the restrictive 1960s when primary Mormon historical publications were often difficult to secure; they continued to be active during the halcyon days of the more liberal 1970s which saw the great flowering of Mormon historical writing; and they show every indication of continuing their publication throughout the 1980s, at a time when serious Mormon scholarship has been forced increasingly on the defensive.

The roots of this extraordinary career lay in Jerald Tanner’s early disillusionment with Mormonism. He had been reared as a Mormon who, in his words, “believed that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God and that I belonged to the only true church.”[6] During his teens, however, he began to feel personally at loose ends and to question the inconsistencies in the historical record of Mormonism. His initial questioning in 1958 did not cause him to reject Mormonism entirely. Rather, he joined Pauline Hancock’s group, headquartered in Missouri, which believed in the Book of Mormon but renounced nearly all other beliefs which distinguish Mormonism from fundamentalist Protestantism. Jerald began holding evening religious meetings in Salt Lake City, while learning to be a machinist during the day.

Sandra McGee entered the picture in 1959 when she attended one of the meetings that the nineteen-year-old Jerald was holding. Prior to that point, she had grown up as a fairly conventional Mormon in the Los Angeles area, although she had been independent-minded, questioning what she had been taught. When Sandra met Jerald in Salt Lake City, she was, as she put it, initially more interested in him than in his religion. “It seemed that the only way I was going to get him, though, was through his religion.”[7] Two months after their first meeting, they were married.

From that point, their joint career gradually developed. Four months after their marriage, Sandra converted to evangelical Protestantism. The couple began putting out fliers, then pamphlets, books, and historical documents, explaining their position and trying to work through their own understanding of Mormonism and where it had gone wrong. From the very beginning, the Tanners’ concerns were not simply doctrinal but also social. Jerald’s fierce opposition to Mormon racism, for example, has been a recurrent motif throughout his career and has contributed to many of his most important re searches into Mormon religious documents such as the Book of Abraham.[8] The Tanners’ publication in 1961 of the complete edition of A Book of Commandments (1833), the earliest book of Joseph Smith’s revelations, marked their first venture into making vital and hard-to-find Mormon historical and religious documents available to a larger audience. Much of the motivation behind such publication appears to have been the polemical one of embarrassing present-day Mormons by showing the inconsistencies and changes in Mormonism since its earliest years. The larger impact of such publication efforts, however, has been to help some Mormons become more aware of their rich heritage and to encourage scholarly attention to the fascinating early days of the Mormon movement.[9]

Another important transition in the Tanners’ career came in 1964 when Jerald quit his machinist job to devote his full time to their anti-Mormon publishing. That work has always been conducted on a shoestring and threatened with closing, due to Jerald’s ill health and the recurrent shortages of funds. The Tanners carry on their publication activities from their large and some what ramshackle old house at 1350 South West Temple in Salt Lake City, across from the Derks Field Stadium, where they also maintain their book store. They named their organization the Modern Microfilm Company because of their initial short-lived use of microfilm, but they soon switched to the more convenient photo-offset process which they have used until the present. Also in 1964, the Tanners put out the first of more than fifty issues of their flier, the Salt Lake City Messenger, an occasional publication which for nearly twenty years has provided a fascinating, albeit polemical, perspective on the latest Mormon controversies, new discoveries in Mormon history, and the state of various anti-Mormon research and activities.[10]

Last but by no means least, 1964 also saw the first publication of the Tanners’ major work, Mormonism—Shadow or Reality? It had appeared previously in briefer form under another title and would later be enlarged in 1972 and 1982 for a final total of more than 600 pages.[11] Mormonism—Shadow or Reality?, which has sold some 50,000 copies to date in its various editions and its 1980 abridgment, incorporates the Tanners’ most important research, discoveries, and allegations which have appeared in their other publications.[12] The 1980 abridgment of the book, entitled The Changing World of Mormonism, was published by the Moody Press in Chicago, suggesting a possible move by the Tanners toward more mainstream evangelical anti Mormon work.[13] Also suggestive of a possible shift in direction was the decision of the Tanners, which went into effect in 1983, to become a nonprofit corporation and change the name of their organization from the somewhat anachronistic Modern Microfilm Company to the Utah Lighthouse Ministry, Inc.[14]

Why was the Tanners’ disillusionment with Mormonism so deep and their hostility toward it so sustained? A key factor was Jerald Tanner’s reaction to his initial naive and unrealistic understanding of Mormonism. As a youth, he appears to have believed that Joseph Smith was perfect and that the Latter day Saint Church had all the answers and could do no wrong. When his research increasingly showed him that Joseph Smith had flaws, that the eternally true (and some assert, changeless) Church had in fact changed, and that Mormon leaders had sometimes made mistakes, even very serious ones, he was furious. He felt that he had been cheated—sold a bill of goods—that the Church had willfully lied to him about matters of the highest importance. Not only did the emperor have no clothes, but the Mormon Church had sold them to him! The anger, even fury, that emerges from much of the Tanners’ writing, with its frequent obtrusive underlining, LARGE CAPITALS, and LARGE CAPITALS WITH UNDERLINING, along with sharp attacks on the personal motives of Joseph Smith and other Church leaders, seems to be crying out for the Mormon Church either to prove that it is perfect or else cease making its exclusivistic truth claims.[15]

Sandra Tanner summarized this aspect of their feelings toward Mor monism when she observed:

I see the Mormon Church leadership failing to come to grips with the problems in their own history. They won’t even admit there are problems. . . . Certainly there are problems in the history of any group of people you get together to do any thing, . . . but the difference is, Mormonism is claiming they are The Church that God’s directing, as opposed to all the other ones just doing it on manmade ability. So when you make that kind of a distinction, one expects a better performance rec ord. . . . They are not just saying that they are a nice church down the street that’s doing a little better job than the Baptists, they’re claiming to be the only true one and that the very sincere Baptist minister is totally wrong. . . . When they make those kinds of specific claims, I expect their history to conform with the kinds of claims they make for it.[16]

Yet there was surely more to Jerald Tanner’s hostility than a purely intellectual disillusionment with his childhood understanding of Mormon truth claims. Many people who have become intellectually disillusioned with Mor monism have nevertheless continued to express appreciation for the Mormon lifestyle and the culture which the Church has helped to create. While the Tanners do make perfunctory acknowledgment of Mormon social strengths, their overall tone is far more bitter than that of the average ex-Mormon. Per haps this is because Jerald’s social as well as intellectual contacts with Mor monism appear to have been disappointing. As described in the Faulring interviews with Sandra Tanner, Jerald’s family life seems to have been filled with stress. Both he and his family appear to have been isolated from many positive aspects of Mormon culture. His father developed a drinking problem, and Jerald himself, during his teenage years, began to drink so heavily that for a time he feared that he might become an alcoholic. Some of Jerald’s Mormon friends also were outsiders who drank and did not conform to the ideal pattern which the Church has sought to develop.[17] Quite possibly Jerald’s failure to find satisfying social contacts in the Mormon Church contributed to the deep bitterness which he eventually developed toward it. In comparison, Sandra Tanner, whose social experiences with Mormonism while growing up were positive, expresses a more balanced understanding of the personal appeal of Mormon culture, even when she criticizes specific Mormon truth claims.

Whatever the roots of Jerald’s disillusionment and bitterness may have been, the factors which have sustained the Tanners’ anti-Mormon activities over more than two decades also call for explanation. Of prime importance was the cooperative relationship which developed between Jerald and Sandra Tanner. Neither individual alone could have been as effective; together they have compensated for each other’s weaknesses and have developed a remark ably strong partnership. Jerald, an intense and almost painfully shy man, is primarily responsible for the research and writing. His own drive, more than any other factor, sustains their operation. Whether Sandra would even have become an active anti-Mormon had she been by herself is open to question. On the other hand, Jerald would hardly have been effective by himself either. Sandra, a warmer and more outgoing personality, takes major responsibility for dealing with the public. Whereas Jerald is often socially inept and strident in his writing, Sandra conveys real warmth and caring that only close associ ates have the opportunity of experiencing with Jerald. Together the Tanners have reared a family and have developed an unusual career for themselves, a career with far more intellectual challenge than the machinist position that Jerald initially intended to pursue.

Accidents of history also helped the Tanners’ career of exposure to develop. Jerald had the good fortune of beginning his anti-Mormon writing and publication at a time when Mormon intellectuals were already independently becoming increasingly self-conscious about their past and seeking to under stand it better. In the early 1960s, most nineteenth-century Mormon publications could be found in a few major libraries, but only dedicated and assiduous scholars were able to locate and work with them. When the Tanners began publishing complete and scrupulously accurate reproductions of classic early Mormon documents which were in the public domain, that publication opened up the possibility of serious home study. A small but significant market began to develop among Mormons who wanted to be able to explore their own past, even though they might resent the Tanners’ other, purely polemical tracts. Yet support was often tenuous. On at least one occasion, in 1966, the Tanners considered giving up their publication work and instead going to Africa as missionaries.[18] They nevertheless remained, largely because their own career and polemicism increasingly tied them to Mormonism, albeit as critics not believers.

To understand the Tanners’ career, their approach must be compared to that of four other types of people who have sometimes sustained an unconventional relationship with Mormonism. One group with whom the Tanners have often been erroneously linked is the professional historians, whose chief goals have been to reconstruct the Mormon past and help modern Mormons better to appreciate their distinctive heritage.[19] Second are the “closet doubters,” individuals who have quietly bracketed their points of uncertainty or dis agreement with Mormonism while continuing to be active and creative participants in the Church, primarily for social reasons.[20] Third are the embittered ex-Mormons, who have given up not only Mormonism but all other religious belief, convinced that if Mormonism is not “true” then no religion is.[21] Fourth are the ex-Mormons who have converted to an alternative religious faith and are actively trying to convert Mormons to that faith as well. These four groups differ widely in background and motivation, yet sometimes they all have been assumed to fit into one mold.

Despite some similarities with each of these groups, the Tanners have close affinity with only one of them. Unlike the Mormon historians who try to understand the Mormon past so that the Church can more effectively deal with the present, the Tanners seek to use every bit of historical evidence they can find (even if it would seem objectively favorable to Mormonism) to attack the Church. The Tanners also have little in common with the “closet doubter,” since the Tanners now feel that they already “know” that the Mormon Church is “false” and hence are only collecting evidence to support that predetermined position. Likewise, the Tanners differ from those disillusioned ex-Mormons who have rejected not only Mormonism but all religious truth. While the Tanners do retain from Mormonism a belief that a religion is either “true” or “false,” they are convinced that they have located ultimate truth in their new faith—which happens to correspond to fundamentalist Protestantism.

The institutional embodiment of the Tanners’ faith is a relatively small evangelical Protestant denomination of some 200,000 members worldwide known as the Christian and Missionary Alliance. The Tanners and their three children have been active in that church in Salt Lake City for over a decade. Jerald serves as an elder in the church and is involved with various social out reach activities. When the Tanners write about their own religious convictions, as in A Look at Christianity, they avoid discussing their specific institutional affiliation and instead focus, in typical Protestant fundamentalist fashion, on the importance of conversion, being “born again.”[22] By contrast to the often harsh rhetoric of their attacks on Mormonism, in person they can be kind, even gentle individuals. Disciplined, hardworking, and committed, they might seem to be almost an ideal model for Mormon missionaries—except that they have devoted their lives to trying to destroy the Mormon Church.

II

What have the reactions of Mormon scholars been toward the Tanners, and what significance has their work had for the development of Mormon historical studies? To say that Mormon intellectuals have been ambivalent about the Tanners would be an extreme understatement. While many Mormon scholars are disturbed by some of the same Latter-day Saint weaknesses that the Tanners also criticize, the scholars’ dissatisfactions derive from an almost wholly different perspective than that of the Tanners. Many Mormon historians, for example, dislike the way in which the conservative element of Mormon leadership has frequently made access to the Church’s own records difficult for even its finest and most loyal scholars and has in subtle and far from-subtle ways controlled, rewritten, or even suppressed candid scholarly studies of the faith.[23] If Mormonism is, as it claims, the true religion, then its history, if properly understood, should support that status. Many of the finest Mormon historians thus believe that the full truth, if fairly and honestly portrayed, would best serve the long-term interests of the Church.

By contrast, the Tanners are critical of what they term the Mormon “sup pression” of documents and evidence for a very different reason: they believe that the full record of Mormonism, if it could be made available, would utterly refute the Church’s truth claims and lead to the destruction of the faith. At every point, the Tanners see fraud, conspiracy, and cover-ups. They always assume the worst possible motives in assessing the actions of Mormon leaders, even when those leaders faced extremely complex problems with no simple solutions. And the Tanners judge the validity of Mormon beliefs not so much within the context of the Church’s own framework as by contrast with a normative Christianity which early Mormonism emphatically rejected and claimed to supercede.

Such radically different approaches lead to radically different uses of identical evidence by historians and by the Tanners. In general, the primary goal of the historians has been to understand and appreciate the remarkably complex and multi-faceted movement that constitutes Mormonism. Toward that end, Mormon historians, like historians in all fields, seek to sift through all pertinent evidence in order to reconstruct the fullest possible picture of the past and its significance for the present. Both positive and negative factors are candidly considered in trying to come to a realistic understanding of Mormon development.

By contrast, the Tanners sound like high-school debaters. Every bit of evidence, even if it could be most plausibly presented in a positive way, is represented as yet another nail in the coffin being prepared for the Mormon Church. There is no spectrum of colors, only blacks and whites, good guys and villains in the Tanners’ published writings. Even when the Tanners backhandedly praise objective Mormon historical scholarship, they do so primarily as a means of twisting that scholarship for use as yet another debater’s ploy to attack the remaining—and in their eyes insurmountable—Mormon deficiencies.

All too often, the Tanners’ work thus simply provides a mirror image of the very Mormonism that it is attacking. The Tanners have repeatedly assumed a holier-than-thou stance, refusing to be fair in applying the same debate standards of absolute rectitude which they demand of Mormonism to their own actions, writings, and beliefs. Whereas the Mormon Church, for example, has frequently argued that the end (supporting Mormonism) justifies the means (withholding or suppressing evidence), the Tanners have, in effect, simply reversed the argument while continuing to use the same true-false framework. They argue that the end (destroying Mormonism) justifies the means (publishing anything which they believe could prove damaging to Mormonism).

This ends-justifies-means approach extends not only to reprinting older published Mormon or anti-Mormon works which are now in the public domain or to reproducing archival material without authorization. It also includes publishing contemporary scholarly work of living individuals without their permission. As my own interview with Jerald and Sandra Tanner on 10 May 1982, indicates, they genuinely appear not to see themselves in violation of United States copyright law or Christian ethics when they published a scholarly paper without any attempt to secure the permission of its author.[24] Behavior such as this has caused even some Mormon scholars who are critical of Mormon Church restriction of access to documents and writings to become frustrated and angry about the Tanners’ methods.

The Tanners’ own writing style is also essentially a mirror image of that of unsophisticated Mormon writers. The stereotypical Mormon thesis in his tory or religious studies, for example, begins with a ringing affirmation of faith in the Mormon Church, is followed by a long and poorly digested presentation with obtrusive block quotations and little analysis, and ends (no matter what has been said previously) with yet another ringing affirmation of faith in Mormonism. The Tanners’ basic format, by contrast, begins with a sharp attack on Mormon perfidy, is followed by numerous long quotations interspersed with purple prose, and ends (no matter what has been presented) with a ringing denunciation of the vile delusion of Mormonism. One cannot help but be reminded of James Thurber’s parable of “The Bear Who Let It Alone,” the moral of which was “You might as well fall flat on your face as lean over too far backward.”[25]

Yet if the Tanners’ own work falls short as history, it nevertheless has helped stimulate historical studies. Jerald is a brilliant analyst of detail, with an almost uncanny ability to spot textual inconsistencies which call for explanation. His analysis showing that a pamphlet denunciation of Mormonism attributed to Oliver Cowdery was, in fact, a clever forgery, is only one example of research and analysis which would do credit to any professional historian.[26] By compiling most of the major published sources bearing on controversial topics in Mormonism, the Tanners have highlighted issues which need to be resolved. For example, I found their study of Mormon polygamy very useful as a compilation of primary evidence on that topic when I was preparing my study, Religion and Sexuality. Although my own conclusions ultimately were very different from those of the Tanners, their prior search of the literature saved me much time and alerted me to issues I would need to resolve.[27]

The impact of the Tanners’ publication of primary Mormon printed documents also must not be underestimated. Those who began their scholarly work on Mormonism during the more open period of the 1970s may find difficulty realizing the problems which earlier scholars encountered in gaining ready access to basic Mormon publications. Even essential early journals such as the Evening and Morning Star, Messenger and Advocate, Elders’ Journal, Times and Seasons, and Millennial Star were all but unavailable to the general public until the Tanners began their republication. That republication and the controversy associated with it in turn stimulated further efforts by other publishers and even the Mormon Church itself to reprint its own writings. Yet without the goad provided by independent critics of the Church, such activity might well have proceeded more slowly, if at all.

A third and much more problematic impact of the Tanners on Mormon scholarship has come through their unauthorized publication of Mormon archival materials. Although such publication has been relatively infrequent, it has generated some of the most sensational cases and has produced the greatest distress among both Mormon scholars and the hierarchy alike. Usually the Tanners have published brief extracts or short documents such as letters. In themselves, these documents are interesting but usually not particularly sensational—until the Tanners’ unauthorized publication generates controversy. The precise channels through which the Tanners have secured copies of some of the documents have understandably remained secret. In cases in which their general methods are known, however, the techniques by which their materials have been acquired appear to leave much to be desired, ethically speaking.

The most problematic recent case involved publication of extracts from the Nauvoo diary of William Clayton, Joseph Smith’s private secretary. Typed extracts from the diary which had been made legitimately by Mormon historian Andrew Ehat were photocopied and distributed without his knowledge or permission by a third party. When the Tanners secured the items, they proceeded to publish them despite the strenuous objection of the historian. On March 21-23, 1984, Justice A. Sherman Christiansen of the U.S. District Court in Salt Lake City heard the suit against the Tanners brought by Ehat. Ehat had charged unfair business practices and asked for damages. The deci sion awarded him $15,960 in damages: $960, which was the amount of profit the Tanners admitted making, $3,000 for the estimated reduction in market potential of Ehat’s thesis in which he had cited the Clayton diary, and $12,000 in general damages for “loss of reputation and other intangibles.” The judge also denied the defendant’s request for punitive damages and agreed to hear further argument on Ehat’s restraining order which would have prohibited their further use of the material. The Tanners announced plans to appeal the case to the Tenth Circuit Court and, if necessary, to the U.S. Supreme Court. Even if the verdict had been otherwise, such publication of stolen notes violates standards of ethical scholarship and increasingly hinders legitimate efforts to secure access to vital documents needed for serious research.[28]

Despite the Tanners’ extensive publication record and the hostility that they have aroused over the past two decades, to date virtually no serious public analyses of their work have appeared. When the Tanners’ arguments have been attacked in Mormon publications, as has occurred on many occasions, their names and the titles of their writings have almost never been cited. Indeed, until very recently even independent Mormon scholarly journals such as DIALOGUE and Sunstone, which discuss all manner of controversial issues, have largely avoided mentioning the Tanners by name, much less analyzing their work explicitly.[29] What accounts for this reluctance to discuss the Tanners?

The Tanners’ answer is simple: The Mormon Church is afraid of them. In their view, it has been engaged in a “conspiracy of silence” because it can not answer their objections.[30] The Tanners argue that if the Church were to try systematically to answer their objections, it would realize the error of its ways and collapse. By failing to deal with them directly, the Church, in the Tanners’ opinion, is providing yet another proof of its underlying fraudulence and repressive mind control.

This interpretation fails to deal with many complex factors which have contributed to Mormon reticence about discussing the Tanners in print. The most obvious point is that neither conservative nor liberal Mormons think that the Tanners are really serious about wanting a truly open discussion or considering approaches which differ from their own chip-on-shoulder anti-Mormon mindset. On the one hand, the Tanners have repeatedly demanded that Mor monism live up to standards of rectitude impossible for any human organization to achieve or else give up its truth claims. On the other hand, the Tanners simultaneously tell the Mormon Church that even if it were somehow able to live up to its impossibly high standards, it still would be false because it is not normative Christianity as they understand it.

In short, probably nothing that the Mormon Church could realistically do in the foreseeable future would satisfy the Tanners. They have set up a logically closed system within which they can refute Mormonism to their satisfaction either if it is true to its original distinctive mission or if, as now appears to be happening, it increasingly seeks to moderate its historic uniqueness and adopt a position closer to the Protestant fundamentalism which the Tanners themselves espouse. The Tanners seem to be playing a skillful shell game in which the premises for judgment are conveniently shifted so that the conclusion is always the same—negative. For example, the Tanners could attack the Mormon Church for its racist policy on the participation of blacks prior to 1978; but after that date, when the policy was courageously eliminated, they turned around and attacked the Church on the grounds that it is supposedly all-knowing and changeless on matters of principle.[31]

Faced by such resolute unwillingness to consider anything Mormonism does in a positive light or to engage in a constructive dialogue about differing approaches, the Mormon Church as an organization has understandably chosen to ignore the Tanners as much as possible. By the Tanners’ own admission, their following is a small, albeit loyal, one.[32] The Church sees no advantage in lowering itself by engaging in vitriolic polemic with virtual unknowns and thereby giving them publicity. A much more effective approach is to try to stand above the battle. Furthermore, as the knowledge somehow percolates through the Church that there are still nasty apostates somewhere attacking the true faith, average Mormons are thereby encouraged to further support the Church.[33]

The reluctance of Mormon intellectuals to discuss the Tanners in writing has more complex roots. Initially, serious historians were just getting into the relevant primary material and trying to make sense of it themselves. While these scholars had a better understanding of some of the difficult issues that the Tanners highlighted, their understanding was at first very tentative and certainly not sufficiently developed to go into print. The historians also had problems of their own as their research began leading them into a slow but major reconstruction of Mormon history (and most recently, theology) which itself posed a substantial challenge to the conventional wisdom of present-day Mormonism.[34]

The difficulties which Mormon intellectuals have had in addressing the Tanners’ arguments directly are most vividly suggested in the exchange which ensued when an anonymous “Latter-day Saint Historian” published a sixty three-page critique of their work in 1977 entitled Jerald and Sandra Tanner’s Distorted View of Mormonism: A Response to MORMONISM—SHADOW OR REALITY? Couched in the form of a reflective personal letter to a friend who is represented as a recent convert to Mormonism troubled by reading the Tanners’ work, the pamphlet skillfully assesses some of the limitations of the Tanners’ perspective on Mormonism. Equally revealing of the Tanners’ strengths and limitations was their own rejoinder, first published in February 1978 and then enlarged in November 1978, entitled, Answering Dr. Clandes tine: A Response to the Anonymous LDS Historian.[35]

The Latter-day Saint historian’s critique of the Tanners begins by expressing a personal faith that questioning and assessing the evidence supporting belief is “a legitimate part of the process of spiritual understanding.”[36] The main point of the pamphlet is that the Tanners’ analysis is deficient from an historical perspective because, rather than trying to describe and analyze the full complexity of historical events, the Tanners’ writing, like that of Mormon apologists, only presents one side of the picture. Moreover, their picture is logically flawed because they fail to apply the same “inflexible standards of criticism” which they use on Mormonism “to the rest of sacred history.”[37]

. . . Jerald and Sandra Tanner have read widely enough in the sources of LDS his tory to provide that [larger] perspective, but they do not. Although the most con scientious and honest researcher can overlook pertinent sources of information, the repeated omissions of evidence by the Tanners suggest an intentional avoidance of sources that modify or refute their caustic interpretation of Mormon history.[38]

After looking briefly at some of the other logical and stylistic inadequacies of the Tanners’ writing when viewed as professional history, the account then presents an important, if rather apologetic, analysis of several complex issues in Mormon history, including Joseph Smith’s First Vision, the process of revelation in Mormonism, and the “translation” of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham.[39] Returning to its larger theme that the Tanners are guilty of using a double standard of evaluating evidence, the pamphlet concludes:

The Tanners proclaim themselves as crusading Christians against a monstrous anti Christ yet much of that which they ridicule about Mormon history and scripture is fundamental to Judeo-Christian sacred history and scripture. The Tanners’ attack on Mormonism is really a manifestation of their rejection of institutionalized religion… .[40]

The Tanners’ response to this critique initially focused not so much on the substance of the criticism as on the question of authorship. With typical polemical flare they began their rejoinder by dubbing the anonymous author “Dr. Clandestine,” devoting their first ten pages of the original twenty-two to a furious assault on the cowardly character of the dastardly individual who would make such an attack on them anonymously. Then they identify the probable author anyway.[41] Reading their polemic, one is amused at the ex aggerated sense of self-importance that the Tanners’ rejoinder reveals. They spent nearly half their original pamphlet before addressing the substance of the criticisms that had been raised against their work. The tone is suggested by the dramatic subheadings with which they start: “From Ambush,” “A Cover Up,” “The Church’s Fingerprints,” “Tracking the Mysterious Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc,” “Stonewalling,” “Cover Up Breaks Down,” “A Fictitious Letter?” and “Honest Works Anonymous?”

One wonders if the Tanners were not revealing their own confusion and thin skin in replying to what appeared to be a mild-mannered Clark Kent as though he were really a Superman in disguise. How could anyone who had unleashed the volume of invective that the Tanners have on the Mormons react with such outrage and seeming surprise to a generally fair, if critical, analysis of their own efforts? The Tanners’ own response would seem to be the best possible vindication of the argument of their anonymous critic that they lack a sense of balance and perspective.

In contrast to their unconvincing character assault on the author of the anonymous critique, the Tanners’ response to specific criticisms of their work score a number of valid points, although in general the Tanners are much more adept at identifying the trees than seeing the forest. In the original edition of their rebuttal, for example, the Tanners convincingly establish their own meticulousness in gathering data and presenting it accurately.[42] They also show that their interpretation of one specific case which their critic challenged was, in fact, supported by their evidence.[43] And they argue that their mission cannot properly be construed as a “rejection of institutionalized religion” unless one is prepared to assert that Pauline Christianity is inherently anti-institutional.[44]

Curiously, however, the Tanners try to defend themselves against the charge that they are guilty of using the “straw man” approach as a debater’s ploy, by showing that the historian who criticized them had also, in one instance, been guilty of the same error.[45] (Two wrongs hardly make a right). Even more curiously, they in effect concede that they do not dare to apply the same scholarly standards of evidence to their analysis of the Bible that they do to Mormon writings because to do so, in their opinion, would be to destroy the credibility of the Bible (a view which only makes sense if one adopts the Tanners’ narrow Protestant fundamentalist approach to religious truth).[46]

Although the Tanners sometimes fail to engage their anonymous critic convincingly on the larger interpretive issues, they cut to the heart of the disagreement when they conclude: “Many of the liberal Church scholars like Dr. Clandestine feel that there are problems in the Church but that they must be straightened out gradually. They believe that we are moving too fast. We, of course, do not agree with this thinking and feel that it would take forever to get things straightened out at the rate that most of them are moving.”[47]

The Latter-day Saint historian’s critique and the Tanners’ response to it highlight difficulties that Mormon scholars have in candidly and openly addressing the weaknesses of the Tanners’ position. As the Tanners correctly argue in their response to “Dr. Clandestine,” the primary reason that the pamphlet was produced anonymously was that if their historical critic had put his name to it, he would probably have gotten into trouble with more conservative Church leaders.[48] Historians such as the Latter-day Saint critic are often as profoundly frustrated as are the Tanners by the historical naivete of some Church leaders. The Tanners have made a career of attacking such naivete as though it constituted the essence of Mormonism. In effect, some of the less well-informed Church leaders are providing the very rope by which the Tanners are trying to hang them. Such leaders have confused the truth of Mormonism with their limited understanding of the truth of Mormonism. Many historians are frustrated that their Church, which could have such a strong case to present to the world, has instead often deliberately chosen to make its case in weaker and less defensible ways.

Latter-day Saint historians, in their role as constructive rather than destructive critics of the Church, have great difficulty dealing with a two-front controversy with Church conservatives, on the one hand, and the Tanners, on the other. In order to make an effective refutation of the “straw man” view of Mormonism which the Tanners have conveniently chosen to attack, the historians must also gently point out to Mormon conservatives that their under standing of the faith is incomplete. Conservatives, in turn, have often argued that the historians and the Tanners are bedfellows, when this in fact is not the case at all. The result, in the opinion of many Mormon historians, is that the Tanners’ long-term impact has been to damage rather than to advance serious Mormon historical scholarship. Although the Tanners’ efforts to stir up controversy during the 1960s may have had a constructive role at a time when access to important records was too restricted, their irresponsible actions which continued into the 1970s, when records were generally available to reputable scholars, has served as a convenient pretext which Mormon conservatives have used to justify closing off access to vital Mormon records once again.

III

What has the larger significance of the Tanners been for the development of Mormonism and for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the Latter-day Saint movement as a whole? Religious dissidents often highlight aspects of a religious movement which we might otherwise overlook. They bring to light problems in a faith which need to be resolved and understood before a realistic assessment of a group’s strengths and weaknesses can be made. Although it is easy to dismiss religious dissidents simply as troublemakers or disturbed individuals, they can also play a highly creative role in prodding a faith to clean up its own house and be true to the best in its testimony.

“Career apostates” provide a particularly illuminating angle from which to view religious movements. Such individuals can be seen as occupying a curious midpoint in the spectrum of religious involvement, a continuum ranging from (1) believers of all varieties, through (2) seceders from a religion, (3) career apostates, (4) converts to an alternative religious faith, and (5) founders of new religious movements. Caught betwixt and between the end points of the spectrum, career apostates remain in a sort of limbo, unable either to be satis fied believers in their original faith or to break cleanly with it and develop a positive alternative synthesis of their own. Like the unfortunate divorces who continue to squabble over the financial settlement and custody of the children, rather than moving on to make a new and more happy life for themselves, career apostates tend to define themselves more in terms of what they are against rather than what they are for. Yet their personal ambivalence also may reflect an ambivalence at the heart of the movement with which they maintain such an intense love-hate relationship.

Circumstances play an important role in determining the way in which religious dissidence, including career apostasy, develops. Using the case of Roman Catholicism, for example, one can see a spectrum of responses by the institutional church which helped define the nature of the religious dissidence it faced. At one point, those with an intense sense of religious vocation could be constructively channeled into monastic orders. At another time, similar individuals could be branded as heretics and burned at the stake. And at still other times, individuals such as Martin Luther could break free entirely from the parent body and successfully form a new religious synthesis of their own. Much depended, in each case, on how the parent organization responded to the challenge. Either an extreme authoritarian approach or an extreme laissez faire style could be equally conducive to stimulating dissidence.[49]

Protestantism has been particularly prone to religious dissidence of all kinds. By replacing loyalty to an all-inclusive church organization with an emphasis on individual interpretation of the Bible as the ultimate basis for religious authority, the Protestant movement encouraged fissure, as different individuals found very different messages in the same biblical record. In the United States alone, where the splintering has been most pronounced, there are today at least 1,200 distinct religious organizations, the majority of which claim to base themselves on the same biblical record.[50]

Mormonism, reacting against the cacophony of religious claims in nineteenth-century America, sought to return to an authoritative Church structure with similarities to that of Roman Catholicism.[51] A major goal of Mormonism was to create a New Israel, a total culture stressing salvation by works rather than the more conventional Protestant emphasis on the Pauline concept of salvation by faith. At the same time, however, Mormonism retained the Protestant emphasis on individual Bible interpretation and, in fact, went still further by developing the concept that continuing revelation, including new scripture, was possible in different dispensations. The result, rather paradoxically, has been that the authoritarian Mormon movement has produced more splintering and diversity than that found in any comparable Protestant group, with the exception of the Baptists. At latest count, more than 150 identifiable Mormon factions have emerged during the first 150 years of the movement.[52]

The diversity within the Mormon movement is by no means necessarily a sign of weakness. Many students of religion have argued, in fact, that a key to the success of a religious movement is its ability to hold seemingly contradictory elements in tension within itself. This is true because reality is always more complex than our verbal understanding of it can be. The word water, for example, cannot convey the full characteristics of the substance that we know as water. Similarly, talking about religious experience or formulating credal statements of belief is not the same as having a religious experience one self. As in the case of the blind men and the elephant, the full complexity of reality invariably eludes our limited understanding.

Both Christianity and its Mormon offshoot provide classic examples of religious movements whose success has been based, in part, on their ability to hold apparent opposites in creative tension. Christianity, to use only one possible illustration from the movement, maintains that Jesus Christ was simultaneously “wholly God” and “wholly man.” While this is a paradox and a logical impossibility, it has proved a remarkably durable and effective belief—so long as both sides of the paradox are maintained. Similarly, one of the greatest non Mormon scholars of Mormonism, Thomas F. O’Dea, argues that the great strength of the movement lies in its ability to maintain a creative tension be tween seeming opposites—hierarchical structure and Congregationalism, rationality and charisma, consent and coercion, conservative family ideals and equality for women, political conservatism and social idealism, patriotism and particularism, and so forth.[53]

Thus, much of what the Tanners view as inconsistency and weakness in Mormonism may actually be an inevitable feature of the movement which can contribute to its success. If Mormonism were as onesided as the Tanners’ analysis (and that of some of the more naive Church leaders whose perspectives the Tanners criticize), then the faith might well have had far less appeal. Like the leaders of many Mormon splinter groups, including the Mormon fundamentalists who practice polygamy, the Tanners have emphasized only one side of the paradox of Mormonism. They have assumed that Mormonism must be eternally true and unchanging when one of the most distinctive affirmations of the movement is its claim to receive “continuing revelation”—its ongoing effort to find new ways whereby principles believed to be eternally valid can better be understood and creatively expressed in the face of ever changing temporal circumstances.

The Tanners assume that Mormonism is “false” because it deviates from Pauline Christianity. By the same reasoning, however, Christianity could be said to be “false” because it deviates from orthodox Judaism. If such a standard of religious truth were universally and consistently applied, it would negate the possibility of religious development and creative change. As Jesus observed, “new wine must be put into new wineskins” (Matt. 9:17). Mor monism under Joseph Smith claimed to be a new revelation which included yet also superseded all previous human truth in a new synthesis for the “dispensation of the fulness of time.”[54] Whatever one may think of this assertion, it must be taken seriously in any balanced analysis of the Mormon movement.

Yet if the Tanners’ understanding of the dynamics of Mormon development is incomplete, their criticisms do highlight disagreements within the movement which must be handled constructively if Mormonism is to remain healthy. Since World War II, Mormonism has experienced a phenomenal four-fold increase in membership. Many converts have come from the Baptist churches and from other Protestant fundamentalist groups whose underlying beliefs are sharply opposed to those of earlier Mormonism, including Mormon notions of the Godhead and continuing revelation. Faced by the onslaught of such new members and the Mormon desire to convert Protestant funda mentalists, the Church has increasingly backed away from or even begun denying some of its earlier testimonies. A certain ossification and rigidity of belief have begun to develop as present-day Mormon leaders try to move away from the free-wheeling speculation of earlier years. Mormons are increasingly talking about and suffering expulsion for “heresy,” a concept which was largely absent from early Mormonism.[55] It is supremely ironic that a present-day Mormon leader could include among his list of the “seven deadly heresies” of Mormonism at least one belief which was firmly held by major nineteenth century Mormon leaders such as Brigham Young.[56]

In the face of such misunderstanding or misrepresentation of the record of Mormonism by some Latter-day Saints, the Tanners have sometimes played a positive role. Every organization, especially if it is highly authoritarian, is dependent for its ongoing health and vitality on its critics, both internal and external. Such individuals, whatever their motives may be, often provide essential information which might otherwise be overlooked, blow the whistle on errors and excesses, and in general help force the organization, whether it be religious or secular, to live up to its ideals and to keep honest, fit, and trim. In the secular sphere, for instance, Ralph Nader has made inestimable contributions to the health and vitality of American business, even though many businessmen have an intense personal aversion to him. By repeatedly, effectively, and with incontrovertible evidence, alerting the public to illegal, shoddy, and dangerous business practices, Nader has spurred many different enterprises to improve their products, making them safer and more competitive.

Jerald and Sandra Tanner have functioned in certain respects with regard to Mormonism in much the same way that Ralph Nader has functioned with regard to American business. While it is arguable that the Tanners’ criticisms have been motivated purely by polemical intent and not, as in the case of Ralph Nader, by shared belief in basic principle, their criticisms nevertheless have not been without positive impact. The Tanners have challenged the Mormon Church, if it really believes in its own ideals, to live up to those ideals. They have challenged the Mormon Church, if it really believes in its own history, to find out what that history was. They have challenged the Mormon Church, if it purports to be a universal church, to correct its sectarian provincialisms such as its former policy of excluding blacks from full church membership. While such challenges obviously have not been popular and the Tanners have generally failed to give the Church due credit when it has met them, nevertheless through such challenges the Tanners have prodded the Church, however haltingly and imperfectly, to begin to develop a more realistic sense of itself.

The complex love-hate relationship which the Tanners have sustained so long with the Mormon Church must not be forgotten. By devoting nearly twenty-five years of their life to attacking Mormonism, the Tanners have borne the most eloquent possible witness to the importance which they ascribe to the Mormon faith, even though they view it as being mistaken. In discussing their motives, the Tanners quote a powerful letter from Duane Stanfield which explains why some “apostate Mormon and anti-Mormon critics” of the Latter day Saint Church devote so much time and energy to their cause:

I would say it’s because they feel the truth is important; in fact nothing really matters in life but the truth. They feel that they had found the truth, and they gave it their heart, mind, and strength; and then found themselves to be, as they felt, in error. And when you have been deceived on such a scale, you want others to know about it, just as one so dedicated and committed wants others to know about the [Mormon] Gospel.[57]

Mormonism appears to have disappointed the Tanners because they found it unable to provide them with a sense of total religious security, a faith which had all the answers. Instead, the Tanners have turned to Protestant funda mentalism for such security. Yet the painful irony is that if the Tanners had put the same effort into analyzing Protestant fundamentalism that they have into analyzing Mormonism, they would have realized that Protestant funda mentalism is also a historically limited movement which ultimately cannot provide them with the total religious security which they are seeking.

Far from being the unique and eternal message of true Christianity in the way that the Tanners see it, Protestant fundamentalism is itself an historically limited interpretation of Christianity. It developed out of a nineteenth-century counterreaction to new currents of thought, including the higher biblical criticism and new scientific and anthropological knowledge. Such knowledge appeared to undercut a monistic interpretation of truth. In response, Protestant fundamentalists increasingly demanded rigid adherence to certain specific beliefs such as the “inerrancy” of the Bible and the doctrine of the Virgin Birth. They also rejected or radically reinterpreted scientific knowledge such as that pertaining to evolutionary biology in order to shore up their literalistic interpretation of biblical stories such as the six-day creation account in Genesis.[58]

The result, in the view of many Christians, was that the Protestant funda mentalist movement tended to lose sight of the forest for the trees. Christianity had traditionally adopted a more flexible approach to truth than that put for ward by the fundamentalists. To use only one classic example, Saint Augustine once observed with considerable eloquence:

It often falls out that a Christian may not fully understand some point about the earth, the sky, or the other elements of this world—the motion, rotation, magnitude, and distances of the stars; the known vagaries of the sun and moon; the circuits of the years and epochs; the nature of animals, fruits, stones, and other things of that sort—and hence may not expound it rightly or make it clear by experiences. Now it is too absurd, yea, most pernicious and to be avoided at all costs, for an infidel to find a Christian so stupid as to argue these matters as if they were Christian doctrine; he will scarce contain his laughter at seeing error written in the skies, as the proverb says.[59]

Similarly, nineteenth-century Protestant fundamentalists could spend inordinate amounts of time arguing whether Jonah actually could have been swallowed by a “great fish” and emerged alive three days later, while missing or downplaying the larger message of the book of Jonah.[60] Like the biblical Pharisees, whom Jesus so roundly excoriated, such literalists could “strain out a gnat and swallow a camel.”[61] They were incapable of realizing that deep faith was possible without narrow literalism, a point which has most recently been illustrated in Raymond E. Brown’s masterful and inspiring analysis of the birth narratives of Christ, The Birth of the Messiah.[62]

The Tanners, like many of the Mormon conservatives whose views they criticize, have not yet developed a faith which is sufficiently inclusive to encompass the full depth and richness of a mature Christianity.[63] Yet if the Tanners’ perspective remains limited, their efforts nevertheless call attention to real challenges which the Mormon movement must meet if it is to remain healthy and vital. There are great dangers in being either too rigid or too openminded. Too-great rigidity limits our ability to seek truth wherever it may lead us. Too-great openminded risks leaving us with no vital beliefs or standards by which to judge our complex experiences. If Mormonism is to remain strong, it must continue to achieve a balance between its paradoxical polarities, especially between faith and works.[64] Only time can tell whether Mormonism will be able to live up to its full potential, creatively combining seemingly opposed elements into a compelling new synthesis reflecting that higher truth which is always beyond full human comprehension.

[1] Only two published critiques of the Tanners are worthy of scholarly attention. The most balanced assessment is Ian Barber, What Mormonism Isn’t (Aukland, New Zealand: Pioneer Books, 1981), which unfortunately is largely unknown and virtually unobtainable in the United States. The best-known critique, by an anonymous “Latter-day Saint Historian,” is Jerald and Sandra Tanner’s Distorted View of Mormonism: A Response to MORMONISM—SHADOW OR REALITY? (privately printed, 1977; reprint ed. Sandy, Utah: Mormon Miscellaneous, 1983). Jerald and Sandra Tanners’ rejoinder to the anonymous critique appeared in both an original and an enlarged edition in 1978 as Answering Dr. Clandestine: A Response to the Anonymous LDS Historian (Salt Lake City: Modern Micro film Company). The critique and its rejoinder are discussed in the text of this article. In their chief work, Mormonism—Shadow or Reality? 4th ed., rev. and enl. (Salt Lake City: Modern Microfilm Company, 1982), in the preface (unpaginated) and on pp. 369-369C, Jerald and Sandra Tanner discuss what they see as the inadequacies of the criticisms by Barber and by Robert L. Brown and Rosemary Brown, They Lie in Wait to Deceive: A Study of Anti-Mormon Deception, ed. Barbara Ellsworth (Mesa, Ariz.: Bownsworth, cl981). A relatively balanced journalistic account on the Tanners was presented by Wallace Turner in his The Mormon Establishment (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), pp. 154-63.

[2] For some of the scholarly and religious perspectives which have informed this analysis, see Lawrence Foster, “A Personal Odyssey: My Encounter with Mormon History,” DIALOGUE: A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT 16 (Autumn 1983): 87-98.

[3] The concept of the “career apostate” was developed with regard to the tenacious Shaker apostate Mary Dyer in Lawrence Foster, Religion and Sexuality: Three American Communal Experiments of the Nineteenth Century or Religion and Sexuality: The Shakers, the Mormons, and the Oneida Community, pp. 51-54, based on research conducted in 1974. A precis for a paper applying the concept to Jerald and Sandra Tanner was written in 1975.

[4] For an incisive analysis of the role of dissidents and apostates in Mormonism, see Leonard J. Arrington, “Centrifugal Tendencies in Mormon History,” in Truman G. Madsen and Charles D. Tate, Jr., eds., et al., To the Glory of God: Mormon Essays on Great Issues (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1972), pp. 165-77.

[5] Scott Harry Faulring, “Bibliography of Modern Microfilm Company, 1959—1982,” included in his 487-page “An Oral History of the Modern Microfilm Company, 1959-1982” (Oral History Project, Department of History, Brigham Young University, 1983), is a key source for any serious work on the Tanners. In quotations from it here, punctuation has been standardized. A similar bibliography is also in preparation by H. Michael Marquart. Jerald and Sandra Tanners’ own writings, cited in these bibliographies and throughout this paper, are the most important source for this analysis. Also of special interest is the transcript of the interviews with Sandra Tanner by Scott Faulring, conducted between 24 January 1981 and 5 March 1982, in “Oral History.” The 317-page transcript, as corrected by Sandra Tanner, provides a thorough, year-by-year presentation of the Tanners’ activities as they perceived them. Perhaps the best brief presentation of the concerns underlying the Tanners’ work is found in the interview with Sandra Tanner by James Vincent D’Arc on 19 September 1972, included in Faulring’s “Oral History,” pp. 360-83. An interesting but mis leading analysis which naively links the Tanners and professional Mormon historians is Richard Stephen Marshall, “The New Mormon History” (B.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1977). A nearly complete collection of the Tanners’ writings, as well as the Faulring “Oral History,” is available in the University of Utah Library Special Collections. I am grateful to the staff of the library for their help in researching this article.

[6] Tanner and Tanner, Shadow or Reality? (1982), p. 568.

[7] As quoted by Jack Houston, “The Jerald Tanners vs. Mormonism,” Power for Living, 15 June 1970, p. 3.

[8] A recent presentation of the Tanners’ attack on Mormon racism is in Shadow or Reality? (1982), pp. 262-93. Among the many writings on this topic published by the Tanners, see Jerald Tanner’s three analyses Does the Book of Mormon Teach Racial Prejudice? (1959), The Priesthood (1962), and Solving the Racial Problem in Utah (1962); Mark E. Petersen, Race Problems as they Effect the Church (1963); Jerald Tanner, The Negro in Mormon Theology (1963); Jerald Tanner, Will there be a Revelation Regarding the Negro? (1963); and Jerald and Sandra Tanner’s three studies Joseph Smith’s Curse upon the Negro (1965), The Negro in Mormon Theology (1967), and Mormons and Negroes (1970). These publications are highly repetitious, but their sheer number suggests the im portance that this topic has had for the Tanners.

[9] Several Mormon historians have told me that they are grateful that key published Mormon writings have been made available to a wider audience through the Tanners’ reprints. Also see Marshall, “New Mormon History,” p. 51. Among the Mormon printed and manuscript documents which the Tanners have made available are A Book of Commandments (1833); The Times and Seasons (6 vols.) ; The Evening and Morning Star (2 vols.) ; Andrew Jenson, “Plural Marriage,” in Historical Record 6 (May 1887): 219-40; The Elders’ Journal (1837-38) ; The Pearl of Great Price (1851) ; The Messenger and Advocate (3 vols.) ; The Millennial Star (vols. 1-7) ; Lucy Smith, Joseph Smith’s History by his Mother (1853); Parley P. Pratt, Key to the Science of Theology (1855); Orson Pratt’s Works; Pamphlets by Orson Pratt; Joseph Smith’s Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar; Orson Spencer’s Letters (1891); The Millennial Star (vol. 15); Joseph Smith’s Kirtland Revelation Book; Joseph Smith’s 1832-34 Diary; Joseph Smith’s 1835-36 Diary; Joseph Smith’s 1838-39 Diaries; Lucy Smith’s 1829 Letter; and Clayton’s Secret Writings Uncovered—Extracts from the Diaries of Joseph Smith’s Secretary William Clayton.

In addition to Mormon religious or historical writings, the Tanners have printed many accounts by ex-Mormons, apostates, or others whose writings they view as damaging to the Church. These include David Whitmer, An Address to Believers in Christ; John D. Lee, Confessions of John D. Lee (1880); R. N. Baskin, Reminiscences of Early Utah (1914); Frank J. Cannon, Under the Prophet in Utah (1911) ; John Corrill, A Brief History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (1839) ; Josiah F. Gibbs, The Mountain Mead ows Massacre (1910) ; William S. Hickman, Brigham’s Destroying Angel (1904) ; Stanley S. Ivins, The Moses Thatcher Case; M. T. Lamb, The Golden Bible (1887); Ethan Smith, View of the Hebrews (1825) ; Revealing Statements by the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon; The Temple Lot Case in the Circuit Court of the United States Western District of Missouri (1893) ; Temple Mormonism (1931) ; John Whitmer’s History; Why Egyptolo gists Reject the Book of Abraham; Senate Document 189 (1841) ; William Swartzell, Mor monism Exposed (1840); The Reed Peck Manuscript; E. D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (1834); John C. Bennett, The History of the Saints (1842) ; T. B. H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints (1873); and Brigham H. Roberts, Roberts’ Manuscripts Revealed.

[10] The first issue appeared in November 1964, and the latest issue to date, March 1984, is number 53.

[11] The first edition of what would later become Mormonism—Shadow or Reality? appeared in 1962 under the title, Mormonism: A Study of Mormon History and Doctrine, with 262 pages. The 1964 edition of Mormonism—Shadow or Reality? contained 430 pages, the 1972 edition, 587, and the 1982 edition, more than 600. In the 1982 edition, the Tanners have tried to retain as much of the earlier pagination as possible, by reprinting earlier pages and using letters (5A, B, C, and so forth) for their “Updated Material.” They have also completely rewritten chapters 8 and 22, covering “The First Vision” and “Fall of the Book of Abraham,” respectively. The other major polemical works by the Tanners are The Case Against Mormonism (vol. 1, 1967, 191 pp.; vol. 2, 1968, 182 pp.; and vol. 3, 1971, 165 pp.), and The Mormon Kingdom (vol. 1, 1969, 172 pp.; vol. 2, 1971, 169 pp.). Much of this material was incorporated into subsequent editions of Shadow or Reality?

[12] Shadow or Reality? (1982), Preface.

[13] The complete title is The Changing World of Mormonism: “A Condensation and Revision of MORMONISM—SHADOW OR REALITY?” The book is 592 pages long and has gone through several printings so far.

[14] The reasons for the name change and application for nonprofit status are given in Salt Lake City Messenger, March 1983. A card enclosed with that issue indicates that the request for tax-deductible status has now been approved by the Federal Government.

[15] Sandra Tanner indicates in Faulring, “Oral History,” p. 58, that they have used underlining and capitalization for emphasis because they “have found that the average reader cannot read a page of material and digest it to come up with the most important point. . . .” Clearly, however, such emphasis also suggests the intensity and bitterness of the Tanners’ feelings. In Shadow or Reality? (1982), preface, the Tanners note that they have replaced their earlier machinery with typesetting equipment which allows them to use three different styles of type for their updated material—i.e., regular type for their own statements, bold type for quotations, and italics for book titles . This change will make reading their writings considerably less distracting in the future.

[16] Faulring, “Oral History,” pp. 158-59. Interview of 17 Sept. 1981.

[17] Ibid., pp. 9-11. For Jerald Tanner’s discussion of his teenage drinking problems, see his Is There a Personal God? (1967), pp. 19-20.

[18] Faulring, “Oral History,” p. 83.

[19] Much has been written on the concerns of professional Mormon historians. Leonard J. Arrington’s articles, “The Search for Truth and Meaning in Mormon History,” DIA LOGUE 3 (Summer 1968) : 56-65, and “Reflections on the Founding and Purpose of the Mormon History Association, 1965-1983,” Journal of Mormon History 10 (1983): 91-103, provide the best starting point. A retrospective assessment of the concerns and accomplishments of the professional Mormon historians under Leonard Arrington’s leadership is Davis Bitton, “Ten Years in Camelot: A Personal Memoir,” DIALOGUE 16 (Autumn 1983) : 9—20. The most incisive non-Mormon analysis of the recent development of Mormon historical writing is Martin E. Marty, “Two Integrities: An Address to the Crisis in Mormon Historiography,” Journal of Mormon History 10 (1983): 3-19. Also see Lawrence Foster, “New Perspectives on the Mormon Past: Reflections of a Non-Mormon Historian,” Sun stone 7 (Jan.-Feb. 1982): 41-45.

[20] See D. Jeff Burton, “The Phenomenon of the Closet Doubter, ” Sunstone 7 (Sept.-Oct. 1982) : 34-38 . For Sandra Tanner’s discussion of this issue, see the interview with her con ducted by Jame s V. D’Arc on 19 Sept. 1972, in Faulring, “Ora l History, ” pp . 366-68.

[21] This is one of the most disheartening phenomena associated with exclusivistic religious traditions such as Mormonism, Roman Catholicism, and the Southern Baptist Convention. When individuals become disillusioned with the claims of such groups, they frequently come to view all religion as a childish fraud, an expression of unmet psychological needs, or a self serving means of social manipulation. For an analysis arguing that a mature , nondogmatic religious faith is possible, see Gordon Allport, The Individual and His Religion (New York: Macmillan, 1950). Also see William James’s classic study, The Varieties of Religious Experience, first published in 1902, and Huston Smith, The Religions of Man (New York: Harper, 1958).

[22] The primary statements of the Tanners’ own religious beliefs are Jerald and Sandra Tanner, A Look at Christianity (1971) ; Jerald Tanner, 75 There a Personal God? (1967) ; Sandra Tanner, The Bible and Mormon Doctrine (1971); and Jerald Tanner, Fighting Among Christians (1979). The Tanners’ religious conversion experiences are described in several sources but are most accessible to the general reader in Shadow or Reality? (1982), pp. 567-69.

[23] Examples of such control abound. The pathbreaking narrative history by James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, was published in a very large edition—35,000-—by the Church-owned Deseret Book Company in 1976 and sold out in three years the original printing. To date, the Deseret Book Company has not reprinted the book or allowed it to be reprinted by any other publisher. On a somewhat larger scale, Deseret Book’s contracts for the sesquicentennial volumes on the history of the Mormon Church were also terminated in 1981 and the authors of those volumes were paid a fee proportionate to the degree of work completed and permitted to seek publication elsewhere. For a judicious discussion of the recent restrictiveness regarding the use of Church records, see Linda Ostler Strack, “Access to Church Archives: Penetrating the Silence,” Sunstone Re view 3 (Sept. 1983) : 4-7.

[24] The paper in question was D. Michael Quinn’s “On Being a Mormon Historian.” It was originally presented before the student history association of Brigham Young University as an eloquent response to attacks on Mormon historians which had been made by Mormon apostles Ezra Taft Benson and Boyd K. Packer. Although Quinn decided not to publish the paper immediately, he did circulate some copies to interested individuals. One copy eventually came into the hands of Jerald and Sandra Tanner who published it without any effort to secure Quinn’s permission.

In my interview with Jerald and Sandra Tanner on 10 May 1982, I repeatedly pressed them on the legality and the ethics of such unauthorized reproduction and sale of a scholarly paper. They emphatically denied any implicit or explicit wrongdoing on their part by such publication. Jerald Tanner indicated that he believed that any paper which was being circulated by its author, even to a relatively limited circle of individuals and without charge, was subject to their publication unless it had been formally copyrighted and registered with the Library of Congress. He indicated, moreover, that he considered that Quinn had been “selling” his paper because he had asked one individual from whom they secured the paper for $2 (presumably to cover the cost of xeroxing and mailing). Not being an expert on copyright law, I moved on to the ethics of their action, even if they felt that on the most narrow legalistic technicalities that they could get away with such actions without being sued and convicted. Astonishingly, they also found no moral inconsistency between their professed Christian beliefs—which presumably included the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”—and their actions. Later, however, they in effect acknowledged such an inconsistency when I asked them if they would have published another controversial paper by a leading Mormon historian. In that case, they indicated that they did not and would not have done so because he was a “friend” and to do so might have embarrassed him. Until the Tanners are prepared to abide by accepted standards of scholarly behavior and of common courtesy, they can expect little sympathy from serious historians.

[25] James Thurber, The Thurber Carnival (New York: Delta, 1964), p. 253. Original italics removed.

[26] Jerald and Sandra Tanner, A Critical Look (1967).

[27] Jerald and Sandra Tanner, Joseph Smith and Polygamy (1967). It is interesting that the Tanners have not seen fit to reevaluate their harsh assessment of the origin of Mormon polygamy based on the more moderate and well-informed conclusions of recent scholarship. Their basic approaches to many other topics in Mormon history have remained virtually unchanged over the years, despite the important new scholarly findings which require reassessment of their earlier caustic beliefs.

[28] Gordon Madsen, Ehat’s attorney provided details on the court case. Th e Tanners’ asser tion is: “We have never stolen any document or film, neither have we encouraged nor advised any person to steal from the Mormon Church. ” Shadow or Reality? (1982), p. 576. Yet even if the Tanners have not personally stolen documents, they have nevertheless been willing to publish documents such as the Andrew Ehat notes on William Clayton’s diary which other people have stolen. On the details of the theft and publication, see Seventh East Press, 18 Jan. 1982, pp. 1,11. The Tanners’ perspective on the suit is presented in Salt Lake City Messenger, Nov. 1983, pp. 1-4. Similarly, the Tanners have published an account of the Mormon temple ceremonies which they obtained from a former temple worker who violated his solemn pledge to maintain secrecy about the ceremonies. Shadow or Reality? (1982), pp. 462—73. By engaging in such actions, the Tanners clearly are a party to unethical activity themselves.

[29] A few exceptions should be noted. Grant S. Heward and Jerald Tanner’s article “The Source of the Book of Abraham Identified” appeared in DIALOGUE 3 (Summer 1968) : 92-98. More recently, the Tanners’ views are discussed in Marvin Hill, “The First Vision Controversy: A Critique and Reconciliation,” DIALOGUE 15 (Summer 1982) : 31-46, and in Lawrence Foster, “New Perspectives on the Mormon Past: Reflections of a Non-Mormon Historian,” Sunstone 7 (Jan.-Feb . 1982) : 41-45. In a letter to me on 28 May 1983, Lester Bush explained why DIALOGUE ultimately decided not to review the Tanners’ books Mor monism—Shadow or Reality? and The Changing World of Mormonism despite their hope to make such a review: “We simply had no desire to be drawn into a sensational debate based on fragmentary data and in no way governed by any notion of intellectual responsibility.”

[30] Although the idea is the Tanners’, the phrase is that of the antebellum abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who was a key figure in bringing the question of the ethics of slavery into public discussion. Th e Tanners have attempted to use similarly abrasive and offensive methods to try to force the Mormon Church to pay attention to them and to their arguments.

[31] Shadow or Reality? (1982), pp. 262-93. Th e Tanners express pleasure that the policy itself was changed (a social interpretation), but they argue that such change serves to further undercut Mormons claims to possess true religious authority (a doctrinal interpretation).

[32] Interview of Sandra Tanne r by James V. D’Arc, 19 Sept. 1972, in Faulring, “Ora l History,” p. 377.

[33] Sociologists refer to this phenomenon as “boundary maintenance.” For a fascinating study utilizing this concept, see Kai Erikson, Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1966).

[34] I am indebted to Lester Bush’s letter to me on 28 May 1983, for this line of interpretation.