Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 4

Toward a More Perfect Order Within: Being the Confessions of an Unregenerate But Not Unrepentant Mistruster of Mormon Literature

A title like that might indicate that I’m already half through. But it needed to be long to convey something of a lurid past that calls for “confessions.” “More perfect order within” suggests both the problem and the promise that I see in Mormon literature. I have stolen (I can use the word since these are confessions) the phrase from I. A. Richards; it is part of his definition of “sincerity,” itself a word that may suggest both problem and promise.

I grew up literarily when an accusation of provincialism was as much to be feared as a comment on China from Ronald Reagan or almost any co ment by Interior Secretary Watts. English departments were just discovering that the creations of literature had not ended in 1789, and the mention of an American literature would send colleagues into gales of laughter or, if the suggestion seemed serious, into shocked or embarrassed silence. True, there was some condescending recognition of what were called regionalists in America, including a group that congregated around a little town called Concord. And somehow a couple of adventure stories of boys along the Mississippi were acknowledged as aberrant masterpieces for adolescents. But Moby-Dick had barely begun to surface. Leaves of Grass made only tinny rustles along the edge of literary consciousness. Bolts of melody had hardly flashed from their upstairs hiding place in Amherst. And few indeed were those who knew of any beast lurking in the jungle.

During those enlightened days, to confess that one was interested in—or even that there was such a thing as—Mormon literature would have immediately made one suspect. Long before Robert Thomas arrived at BYU, it was whispered in the halls that he had written a thesis on literary qualities in the Book of Mormon.

I was among the suspicious. I had joined the department directly from my M.A. program at BYU, at a time when, to meet the waves of post-war freshmen pouring over the edges of University Hill, the university was taking almost any half-way qualified instructor. Even in my euphoria over my new position—that dirt farmer and truck driver from Morgan actually teaching English at BYU, teaching with P. A. Christensen and Karl Young and . . .—I must have realized how insecure my position was in the department. I don’t remember ever consciously saying to myself, “I’m going to make sure I am not provincial.” But in retrospect I can see that my fear helped dictate many of my choices in the next fifteen years and much of the way I would teach. It kept me from considering the University of Utah for my doctoral work, though I started immediately taking summer classes there. It probably helped me choose the University of Washington, hardly the most cosmopolitan of universities but cosmopolitan enough for me, especially since that most cosmopolitan friend Leonard Rice was just finishing his work there. It almost certainly determined my strong emphasis on literary theory and criticism at Washington. No one was going to accuse this farmer-trucker of slighting the tough stuff. It probably led me to Arnold Stein, reputedly the most demanding and most frightening of the graduate faculty. Paradoxically, it even helped aim me toward an emphasis in modern literature. I had already overcome my fear of the provinciality of American literature: under the aegis and enthusiasm of Briant Jacobs I had gone diving for Moby-Dick as an M.A. thesis.

In retrospect, I can see that modern lit was something of the “in thing” at Washington. Heilman and Stein were both very much part of the New Criticism. Theodore Roethke was teaching creative writing. But it was a sense of daring that led me to Robert Penn Warren and his fiction. He was complex enough to be demanding, important enough to be respectable, and a personal friend of both Heilman and Stein. But the unconscious motivation, I suspect now, was the image of my colleagues back at BYU aghast at Clark doing a dissertation on a contemporary American novelist, and one who was important in the New Criticism, even then just barely finding its way into BYU.

One hardly needs a psychologist to tell him that such unconscious motivation is only an inversion of the fear of provincialism—that same provincialism that led me to respond condescendingly to my best friend at UW when he told me he was going to do a study of attitudes toward blacks in Countee Cullen, Gwendolyn Brooks, Eudora Welty, and others. Oh, I was interested and prob ably hid my real response well enough, but I remember with embarrassment watching him walk off through the pines for some of his bird watching: “Well that’s all right for him—this going after sociological studies of minor figures. But it’s not for me.”

That attitude changed very little in the dozen years after I returned to BYU. I settled only too comfortably into teaching. But in 1969 something happened to jar both my complacency and my fear of provincialism. We held a convention of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association in Provo; a brief report did the jarring. It simply reported the results of some page counting in the most popular anthologies: of some 37,000 total cumulative pages, twenty-seven pages total were devoted to black literature.

What this report did was jar me into the awareness that I had been teaching modern American literature for twelve years and had never once consciously introduced a work by a black writer into my classrooms. My tender conscience ached, enough to send me on a too-quick trip through black literature for essentially the first time. Oh, I had read Native Son years before and shuddered with its power. I had read Invisible Man and been intrigued. These were fine works—considering they were written by blacks. I reread Invisible Man and marveled; reread Native Son and shuddered again; Black Boy and rejoiced; anthologies of short stories and poems, and rejoiced. Rejoiced even in my shock: this was a substantial body of fine literature, a body that cut the whole base from under my condescension. I repented. I even thought of offering a course in black literature. But Bri Jacobs beat me to it. I did present a lecture sponsored by the Honors Program, which I entitled “Black Literature and the Mormon Dilemma.” I was so concerned about how it would be received that I told my wife to wait for me at the bottom of the stairs, went up to my office to get my materials, then went down a different set of stairs and was ten minutes into my lecture before I remembered my wife waiting there.

I suspect that all this was happening at about the time we were getting the first faint tremors from a project Neal Lambert and Richard Cracroft—two young turks in the department—were moving earth for. An anthology of Mormon literature for a possible class in Mormon literature! What next? But if Mormon literature were simply trivial, why the tremors? I can account for them only by our fear of being provincial—our whole department’s fear, not just mine. I don’t suppose we could have had any real fear that Neal and Richard would embarrass us by uncovering a significant body of literature that the rest of us had ignored.

At any rate, I escaped for a year to Finland. Now here was something both respectable and significant: I could teach American literature as a Fulbright (I love the name) professor at “the northernmost university in the world.”

I came back to an English Department in trouble, like so many other departments in the country, because the market for English teachers had collapsed. (I use that commercial term advisedly, because I fear that was the way we were seeing our profession at the time.) The year before leaving for Finland I had worked vigorously for a Ph.D. program for our department, an over-riding consideration being that we needed to help supply the market. I came back to no market. While the rest of us worked at that problem—which we finally solved for us by putting our Ph.D. program in mothballs—Neal and Richard were not so quietly working away at their project. When A Believing People was published in 1974, we had to face it: a substantial body of Mormon literature that the rest of us had largely ignored.

I don’t know to what extent the publication of A Believing People is re sponsible for the existence of an Association for Mormon Letters. In retrospect one can see quite a few forces all moving toward its development. The launching of BYU Studies in 1959 suggested that the university was ready to give its scholars a medium and accept something of its responsibility for Mormon scholarship. Clinton Larson moved more and more to avowedly religious, Mormon poetry and drama in his own creative work, and also vigorously promoted the writing of poetry among his students. The Mormon History Association had already made historical studies of Mormonism respectable. The Carpenter had made its short-lived but groundbreaking appearance on the scene. The young editors of DIALOGUE had recognized a real need for an independent journal of Mormon thought and had begun, rather daringly, to publish speculative and scholarly discussions of Mormonism. Sunstone and Exponent II helped fill this need.

It should be some comfort that I did not regard these efforts with a sophisticatedly cynical eye. I had essays in the first issue of Studies and the fourth issue of DIALOGUE. I wrote introductions to Larson’s first book of poems, The Lord of Experience, and to his first published plays, Coriantumr and Moroni. I published what I think is the first essay on Larson’s poems, an explication of that remarkably dense and fine sequence, “The Conversions of God,” which end with Larson’s version of the Mormon God. I had even started writing poems myself that I sensed as unabashedly Mormon in many of their emphases.

I can hardly claim, however, that I burned with a conviction of the significance of an established body of Mormon literature. Rather, I sensed the paucity of Mormon literature even while I desired to promote such a literature. My desire to promote was thus at war with my fear of provinciality. Or perhaps it was just another expression of that fear: I wanted a literature that I would not have to feel apologetic about because of its provinciality. I have to confess that I still felt a bit condescending about A Believing People. But I couldn’t show it openly: People were paying too much attention to the book.

In 1976 I spent a remarkable six weeks in the first annual session of the School of Criticism and Theory at the University of California, Irvine. In many ways it was sharply stimulating. I worked with some of the finest critics and theorists in the profession: Rene Girard, Frank Kermode, Murray Krieger, Hazzard Adams, Edward Said. And I was surrounded by brilliant young professors and Ph.D. candidates—among them Jim Ford, who taught at BYU Hawaii and is now at the University of Nebraska. In spite of all my years of teaching criticism at BYU, I felt during the first three weeks like a run-down old jogger suddenly thrown into the sprinting events of the NCAA. What bothered me most was an exotic new critical vocabulary: deconstruct, reify, hermeneutics, sacralize, devalorize, and many more of these—along with that four-letter word which flattens any work of literature into a text. I finally got some control over that vocabulary and over the new ideas that were crackling around me, and I came home renewed as professional development leaves are supposed to renew. But after some of the immediacy of the experience had passed and I was able to look at it with some objectivity, I became more and more troubled by that exotic vocabulary and those ideas and approaches that had so intrigued me. What troubled me was the remoteness of both vocabulary and method from most of what I wanted students to get from literature, even the remoteness from my own most significant experiences with literature. We seemed to be theorizing and vocabularizing ourselves right out of touch with both readers and literature. Was this the end toward which all my interest in criticism and theory—my teaching of criticism—had been leading? Where in all this was the sense of literature as something to experience, as extender and expander of life, as profound exploration into meanings, even as significant form? Through it all, I began to hear, first faintly, then louder, P. A. Christensen’s resonant voice talking of “depth of human experience,” echoing Matthew Arnold’s concerns with “the best that has been thought and said in the world,” with literature as a “criticism of life.”

I want to be fair with both my Irvine critics and myself. They were, of course, concerned with many of these issues, simply looking at them from new and sometimes very revealing viewpoints. They were intensely involved in literature, and most of them loved it. Whatever else, they helped me to know again, and know more deeply, how radically linguistic our lives are, how much of our experience is defined by, even determined by, language, hence how deep at the core of our experience language really is. And I myself had never really gotten as far away as I have been suggesting from the concerns I’ve outlined.

Even so, I could not rid myself of the suspicion in retrospect that much of what we were hearing and doing at Irvine was moving toward an esoteric criticism and theorizing so specialized that it could have little meaning for any but the most advanced students and scholars, that is, for the critics and theorizers themselves, at worst toward a kind of critical bankruptcy.

And what has all this to do with my confessions, with my attitude toward Mormon literature? Well, my experiences at Irvine defined an extreme moment in how far one can go in theorizing about language and literature. My real literary loves have always been poetry, fiction, drama. But I had always argued that one could not understand modern American literature, which I have taught regularly, without understanding Puritan literature. And it doesn’t take much acuteness to recognize that one has to approach early Mormon literature with something of the attitude one approaches early American literature. But not with condescension of “this is fine, given the situation they were in, fine, given the struggle for survival and growth in a new land.” Why not simply, “Fine”? Fine expressions of that struggle. Fine explorations of it. That is what I recognized Puritan literature to be, even if a bit con descendingly. That is what I now recognize early Mormon literature to be. And without any condescension except, perhaps, for some of the wilder flights or barren stretches of Orson Whitney or some of the less happy moments in Eliza R. Snow. (I have never been able to figure out the grammar of “Truth reflects upon our senses, Gospel light reveals to some . . .” Though I do have irreverent fun with the stern theological message of the next two lines set to a lilting waltz: “If there still should be offenses,/Woe to them by whom they come.”) We hardly have to affirm that everything we find back then is great, or even good. What we can affirm, without apology or condescension, is that there is much that speaks to profound levels of our spiritual, moral, and esthetic senses, much that defines movingly what the restored gospel meant to those early Mormons, much that is fine indeed.

And that is quite a ways for a confirmed mistruster of Mormon literature to have come. It takes care of the last, or whimsical part, of my ponderous title. But I want to come still farther. After a long discussion of the pitfalls of judging literature according to the usual senses of “sincerity,” I. A. Richards sums up his own sense of it as “obedience to that tendency which ‘seeks’ a more perfect order within the mind.” That definition comes in the chapter called “Doctrine in Poetry,” in which Richard tries to understand why “most readers, and nearly all good readers, are very little disturbed by even a direct opposition between their own beliefs and beliefs of the poet.” I am not so sure that most readers, especially Mormon readers, are, in fact, so undisturbed. I have seen even good readers rather violently disturbed by such opposition. But when I reflect on how few of my students have been disturbed—though many have been bored—by, say, the deterministic philosophy of Dreiser’s American Tragedy, I suspect that Richards may be right.

In one form or another, sincerity is always with us as a measure of literary worth. It focuses primary attention on the author rather than the work itself or the reader’s response or any idea or system of meanings behind the work or embodied in it. It has strong roots in romantic attitudes and theory. And it is tricky. It can be used to justify the most arrant sentimentality—”Can’t you just feel his sincerity!”—or to explore the depths of the author’s rnind and feelings. Like all tonal questions, it often resolves itself into formal questions, simply because the work itself is often the only evidence we have of the author’s sincerity or lack of it. Sentimentality, the primary expression of artistic in sincerity, nearly always betrays itself in shoddy technique. This kind of sincerity, sincere feelings expressed in insincere forms, we have always with us in the Church.

The second use, to recognize and explore the author’s mind and emotions, is a much more valuable approach to Mormon literature. In a more general sense than Richards had in mind, it is worthwhile to apply sincerity as a measure of much of that early Mormon literature. Arthur Henry King has told us that the eloquent sincerity of Joseph Smith’s story of the First Vision convinced him of the restored gospel. Even in its consciously archaic, quasi biblical language, one finds the specificity of detail, the sense of total conviction that itself convinces. Or test for sincerity the journal of Mary Goble Pay, by now recognized as a minor Mormon classic. The directness of style, the sharpness of detail, the simple factuality, even the unpolished grammar all confirm our sense of genuineness. We could work through much of the early literature for the same confirming sense of sincerity. But that is not really my point.

At least one of my points is that our literature grows out of—perhaps not a seeking for but a responding to—a more perfect order within the mind. That order, of course, was the restored gospel, which gave its early writers at least a fuller sense of order than they had known before. And the excitement of that new fullness carries through nearly everything they wrote. Even when it was written in pain and suffering, even when it carries deep questioning or some sense of rebellion, the writing is informed with that sense of new-found order and the excitement it generates. Listen to two or three excerpts from the journal of my grandmother, Annie Waldron Clark, who married Charles R. Clark as a second wife in the Logan temple, November, 1886, in deep secrecy because of the persecution of polygamists. First her response to the ceremony itself:

It seemed as if the holy angels were witnessing the proceeding in there and we knew they were, for no other spirit, only the spirit of God could wield such an influence. How I appreciate the opportunity of receiving my washing and anointing and making covenants with my Father in Heaven—so solemn and beautiful, and I knew that I was taking a course that the Lord was pleased to acknowledge if I could only endure the sacrifice, for such it certainly was, with fortitude, which I had fully resolved to try to do.

Six months later she prepares to leave home, some four months pregnant:

He came according to appointment, and I knew I had seen the sun sink behind the western hills in Weber the last time for a long time. Imagine my feelings. It was not like leaving home to take up my abode with my husband. It is written “We shall leave parents and home and cleave to our husbands,” but this is not what I knew I had to do for I had to be severed from him and how many hills and valleys would divide us I knew not . . . .

After a day’s travel from Morgan to Farmington, “The Brother met us as expected, and I had to go with a stranger to a strange place.” The “brother” was the father of Grandpa Charley’s first wife, Emma Woolley, and here was my grandmother going to live with Emma’s family—and, except for the parents, not even the family she was living with could know that she was Charley’s wife. Her first son, my father, was born October 6, while Grandpa Charley was at general conference. He stopped for a few minutes on the way; but before that, Grandmother had not seen him for over two months. He was there, as she says, at seed time and harvest. One last excerpt. She is now living with Charley’s family, but no one except Father and Mother Clark and Mary Lissie, the oldest daughter, know who she is. She cannot even attend the wedding of her brother, but “such is the sacrifice I make to live the law of God. .. . I do not have the privilege of going to meetings and Sunday Schools nor any of these things. After having been a regular attender all my life, it is hard to see them all preparing to go but myself.”

Well, this may all be much more moving to me than it is to you. It’s hardly great prose by most standards. But it has the obvious authenticity of deatil and feeling that we associate with great writing. I honor her for it and for what she experienced that produced it. I honor her that she experienced deeply enough and cared enough about those experiences to leave the record.

Let me remind you again of Richards’ definition of sincerity: “Obedience to that tendency which ‘seeks’ a more perfect order within the mind.” The phrase is richly ambiguous, suggesting an already existing order to be sought and found in the mind but also suggesting that the seeking is, or can be, a kind of creating of that more perfect order. The phrase is especially rich for Mormons. If we really are sons and daughters of God and if our destiny is to move somehow toward his condition, then we must have at least latent in our mind the totality of order that he knows and is. The very least we can demand of our Mormon writers, I would say, is the kind of sincerity that seeks to know and reflect and embody this more perfect order and that seeks an even more difficult end—to create from, and in, that matter unorganized a new and more perfect order.

This is hardly a new charge to writers. Until the last fifteen or twenty years nearly all writers of and about literature have seen literature primarily as both means and result of the struggle to bring order and significance to an often chaotic world. None has been more insistent nor more effective in his insistence than Wallace Stevens. As his young lady walks along the shore at Key West, that archetypal and seminal meeting place of land and ocean, she sings not the song of the “veritable ocean” but the song she makes. At once poet and muse, she sings, apparently, because her imagination has been impregnated in this setting and helps her make the song, which stirs the imagination of the poet and his companion, who then see the harbor lights as “order ing” the bay. But the “blessed age for order” does not stop there. The poet, his imagination thus stirred, goes on to create “The Idea of Order at Key West,” which should in turn stir us—to what end we alone can determine. For Stevens the poet is “the impossible possible philosophers’ man . . . Who in a million diamonds sums us up,” the man who replaces the “obsolete fiction” of religion and trivialized mythology.

Like Matthew Arnold, Stevens saw a high destiny for the poet: He would replace a dying or dead Christianity, a dying or dead faith in religion of any kind, with a new mythology, a new life of the imagination, a new order created by that imagination, summed up by Arnold in Culture. We Mormons feel no need to replace a dying Christianity. It has already been given new life in the restored gospel.

Who knows the destiny of the writer in eternal perspectives, the perspectives of the gospel? The Mormon poet may have a real advantage over the Stevens poet, at least theoretically, simply because the order within the mind of the Mormon poet has, or should have deeper roots. He has all the image making, order-making capacity of the Stevens poet plus the capacity that comes from the order of the gospel, the order of the priesthood, the order of the Holy Spirit.

But the advantages do not stop simply with the order within the mind. Within the mind, yes. But within everything that the Mormon poet feels himself or herself part of. The gospel, the priesthood, the Holy Spirit are all within the poet. But they are also outside, universal in some literal sense, and yet encompassed within the Church, as the Church tries to encompass all truth. I use the word encompass with real intent, since many of us carry a constant reminder that, among other things, all truth can be circumscribed into one great whole.

Within the mind, then, but the mind sustained and nourished by all that I have been suggesting. But also within the Church, within that great whole the compass circumscribes. These are the sources of order toward which our sincerity should lead us. If we experience the Church as less than perfect, the members we know as less than perfect, even our own minds as less than perfect, then the nice ambiguity of Richards’ phrase suggests that part of our task is to help each of these seek the more perfect order—either to discover it there or to help create it there or both. If we experience these as perfect already, we can do so only by looking at the gospel, the priesthood, and the Holy Spirit in their ideality, not by looking at the Church or people or ourselves and our minds as expressions of it. If we experience these as perfect, then our sincerity should lead us to make real in literary forms that perfect order, to catch and define that sublimity, to make available to others our sublime vision.

For it is sublime, I hardly need to tell you, this vision of God as Father and Creator, this vision of us as his sons and daughters, this sublime vision of family, this vision of all truth circumscribed in one great whole. It should feed our imaginations as no other vision has ever fed. We may fall short, we may never get our imagination to rise to the vision. But that won’t be the fault of the vision.

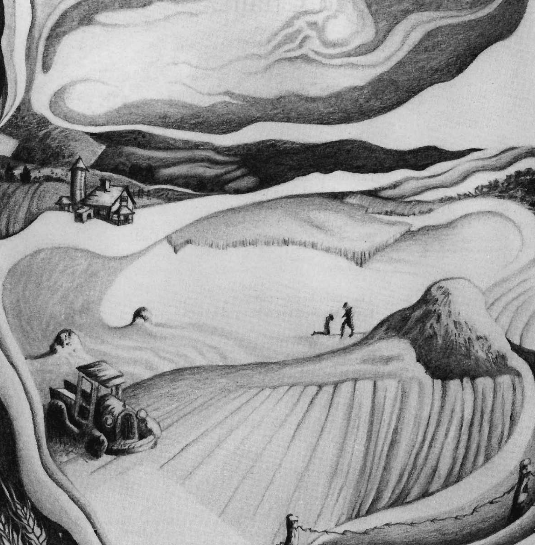

We all sense the beginnings, perhaps more in music and art than in litera ture: in LeRoy Robertson’s “The Lord’s Prayer,” for me the finest setting of that jewel in all music; in Robert Cundick’s Redeemer, in some of Trevor Southey’s works with acrylic sheets, in several of Hagen Haltern’s drawings and in sculptures by Warren Wilson, Franz Johansen, and Dennis Smith. But in literature also. In many of Clinton Larson’s lyrics, in many parts of Emma Lou Thayne’s Once in Israel, in parts of Paul Cracroft’s A Certain Testimony, in Ed Hart’s “To Utah” sequence, in the exquisite agony Douglas Thayer catches in “Greg” of a young priesthood holder who has slipped into sin and now must face his bishop, in the lyric by Allie Howe that Ed and I chose as the first poem in the sesquicentennial volume we were asked to edit for the College of Humanities:

TIMES OF REFRESHING: 1820

Alice E. Howe

A wisp of the new morning

Washes across his face

And turns him to wooded temples.The way along

Winged harbingers lighten above

Through among, back and before,

And unstartled anxious buds

Await nativities.

Under his boot and on

Dark leaf-mold, dew-dampened, patient,

A teeming earth secures.Hearing his step,

The stone beside quickens

To its rolling,

And the showered-clean air,

Ecstatic,

Freshens millennia past,

Whispers everlastings.Ancient-in-days, the awakening earth

Lifts

Against his supplicant knees,

And a breath above,

Reigning all the space around,

The Holiest of Holies

UnveilAnd Joseph sups from Their Presence . . .

You could hardly help feeling the vibrancy of all nature, especially the miracle of awakening earth lifting “against his supplicant knees,” in anticipation of the coming vision. In this, in other things from the same commemorative volume, in much else that is happening all around us, we see the beginnings, beginnings that I trust will bring to full fruit the promise of those earlier beginnings that I now repent of mistrusting.

If I am unregenerate still, it is because I have not done my share, because I want the higher fulfillment, the higher destiny for Mormon writers, the destiny that President Kimball and other leaders have held out to us time after time, the destiny that I have been trying to define. Finally I do not believe it a lesser destiny than that envisioned by Arnold and Stevens. Theirs was after all a substitute destiny in a world bereft of Christianity. Ours is a complementary destiny in a world destined for Christianity.

In good Mormon fashion, I leave the challenge that that destiny imposes upon us: that we fulfill it; that we have the sincerity, which I would now hope would become the intensity and energy and imagination, that will lead us to seek, to create, and to create from that more perfect order within our minds, within the Church, within the gospel of Jesus Christ, and within that one great whole into which the compass circumscribes all truth.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue