Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 1

The Seventies in the 1880s: Revelations and Reorganizing

“These 76 quorums were all torn to pieces.” That disturbing report card for seventies quorums came from Joseph Young, senior president of all seventies in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in January 1880.[1] Such a disrupted state could not long continue, and two “thus saith the lord” revelations to Church President John Taylor—on 13 October 1882 and 14 April 1883—triggered major reconstructions of the work and the quorums of the seventies.[2]

What circumstances prompted the revelations and what responses did they receive? Why was the then-current seventies quorum system malfunctioning? What did the revelations teach and mean in their 1880s context? How fully were the revelations’ instructions implemented? How did the First Council of the Seventy interrelate with the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles regarding seventies’ work? Why was the vacant First Quorum of Seventy not recreated? What differences did the revelations and restructurings make to seventies’ work? What does this episode teach us about the role continuous revelation plays in priesthood history? What seventies problems were left unresolved?

This study draws heavily on seventies’ records—those of the First Council and of individual quorums—and is thus biased towards those sources. The diaries of apostles Franklin D. Richards and Brigham Young, Jr., helped compensate for the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve minutes, unavailable for the 1880s.

The Seventies’ Beginnings

On 28 February 1835, Joseph Smith announced an unrecorded revelation about the seventies, established a new Melchizedek Priesthood office, and created a distinctively structured quorum of seventy men. The seventies, he taught, were to be “traveling quorums, to go into all the earth, whithersoever the Twelve Apostles shall call them.” A month later a revelation on priesthood (D&C 107) specified that seventies were to “preach the Gospel,” “be especial witnesses unto Gentiles in all the world,” be a “quorum equal in authority to that of the Twelve,” “act under the direction of the Twelve .. . in building up the Church and regulating all the affairs of the same in all nations,” and to “have seven presidents” chosen “from their own ranks” who “are to choose other seventy . . . until seven times seventy, if the labor in the vineyard of necessity requires it.” The Twelve were “to call upon the Seventy when they need assistance, instead of any others.” Like the Twelve, the seventies had “responsibility to travel among all nations.”[3]

Joseph Smith further explained that seventies could be multiplied until “there are one hundred and forty-four thousand,” should be taken from elders quorums, and “are not to be High Priests.” Seventies who had previously been ordained high priests were in office “not according to the order of heaven” and were replaced. During the 1830s, a second and a third quorum were organized. In October 1844 general conference the Church voted “that all in the Elders’ Quorums under the age of thirty-five” become seventies, so that by the time of the exodus from Nauvoo thirty-five seventies’ quorums had been created.[4]

To provide leadership for quorums two through ten, the First Quorum divided itself into nine seven-man presidencies, leaving the seven senior presidents of the First Quorum with no rank-and-file quorum members after October 1844. These seven men—the First Council of the Seventy—presided over all seventies and were sustained as Church General Authorities.[5]

The Seventies’ Situation in the 1880s

By 1870, the Nauvoo-instituted policy that a seventy belonged to his original quorum for as long as he was a seventy, no matter where he lived, was creating problems. Utah’s settlement process scattered members and presidents of the same quorum. Although some quorums kept track of their scattering sheep, others dwindled to one or two presidents and a handful of findable members. Seventies from different quorums who lived in the same community sometimes grouped themselves into an unofficial, local, “mass” quorum. By late 1880 it had become “impossible to reach all the Seventies and for the President to teach their members in a quorum capacity, or that they can be brought together as quorums.”[6]

When the decade of the 1880s opened, not only were quorum members scattered and some units disorganized but the quorums had shrunk. Normally when members died, apostatized, or became high priests, their vacancies were filled. But the priesthood reorganization of 1877 turned hundreds of seventies into high priests to fill bishopric and stake positions, then ordered a moratorium on ordaining new seventies—to the great disappointment of Senior President Joseph Young.[7]

Ideally seventies quorums were training and recruiting grounds for future missionaries, but in practice a man received a mission call first and then was ordained a seventy. As a result, by 1880 the quorums had very little official missionary work to do. “In the wards,” one seventies leader said, “there was nothing for them to do, and they became tarnished.” A March 1881 report shows that in at least two stakes the seventies had not met together for “several years.”[8]

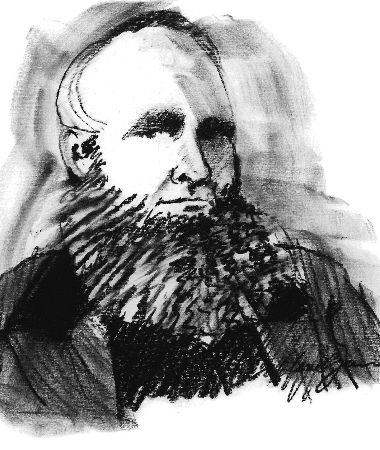

Another problem plaguing the seventies units by 1880 was gray hair. The First Council itself contained only old men. (See Table 1.) Horace S. Eldredge at sixty-three was the youngest and Joseph Young, the oldest, was eighty-two. The others were John Van Cott, sixty-five; Jacob Gates, sixty-eight; Levi W. Hancock, seventy-six; and Henry Harriman, seventy-five. Albert P. Rockwood had died in 1879 at age seventy-five, leaving one vacancy.

In April 1880, eight young men became council “Alternates” by advice of President John Taylor and vote of the general conference. These alternates were expected to carry the load laid down by three aged council members living in southern Utah—Elders Harriman, Gates, and Hancock. In addition, twenty-six-year-old William W. Taylor, son of President John Taylor, filled a council vacancy. These nine new men gave the seventies’ work new vigor. Seeking even more helpers, the First Council talked about filling up its own First Quorum, vacant since Nauvoo.[9]

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1, see PDF below, p. 64]

Scripturally, seventies exist to do missionary work. However, the council possessed no policy-making responsibility for proselyting. The Twelve, without asking for input from the council, determined when, where, and how many missionaries should be sent out, and then asked the council to supply the men.

First Council minutes show that the Twelve, after Brigham Young’s death, stepped up the seventies’ missionary responsibilities and “were now throwing the labor of preaching the Gospel upon this body.” Council records in May 1879 say President John Taylor was “calling upon us constantly” for missionary names.[10]

The First Council, when soliciting missionary nominations, looked mainly to the Salt Lake Stake where half of all seventies quorums were located. These quorum presidencies met in a Seventies’ Council Meeting with the First Council every other week from 1879 (or earlier) to 1884. The meetings were “for preaching missionary purposes” and included short impromptu talks, sermons, quorum reports, and First Council requests for missionary names.[11] Usually thirty to thirty-five different quorums had at least one presidency member there, so missionary business was easy to parcel out. In places beyond Salt Lake, council visits and letters solicited additional nominees.

Temporary Stake and Ward Seventies Presidents

Because missionary demand exceeded supply, the First Council felt frustrated by the chaotic state of seventies units. In the fall of 1880, after exploring ways to communicate with scattered seventies, the council adopted a new organizational structure that established ward and stake seventies’ presidents. A ward president, they reasoned, could become acquainted with and list all seventies residing in his ward, no matter what their official quorums were. If presidents in all wards did likewise, then practically every seventy could be located by ward and identified by quorum. A stake president of seventies could coordinate the ward presidents’ work. After testing in the Salt Lake Stake, the new plan won approval from the Twelve and the First Presidency. Early in 1881 ward and stake seventies presidents were called and instructed. They were considered temporary, not replacements for or competitors with existing quorums and presidents.[12]

During this change, Joseph Young died on 16 July 1881. Eulogies por trayed him as a devout, spiritually-minded man whose instructions were “rich in the spirit and power of God,” a man of “superior wisdom, talent, and ability.” By seniority, ailing Levi Hancock became the new senior president. Joseph’s vacant slot in the Council was not rilled until October 1882 by Abraham H. Cannon, twenty-three-year-old son of George Q. Cannon, first counselor in the First Presidency.[13]

The ward and stake plan’s primary purposes were “to expedite the furnishing of missionaries and awaken Seventies.” The new plan worked well, although some quorums resisted the ward presidents. Newly appointed presidents were instructed that seventies should meet at least monthly, a census of seventies should be sent to the First Council, and families of missionaries must be cared for. Each ward leader was told to compile a list of potential missionaries in his ward by nationality, have the bishop verify the men’s worthiness and ability to go, send the list to be cleared by the stake seventies president and stake president, and then forward it to the First Council, usually preceding the twice-yearly general conferences. Approved nominees received form letters from the council asking if they could accept mission calls, provide for their families during the absence, and pay transportation costs out. Nominees answered by letter or in person.[14]

One sampling, the verbal and written responses of 1 and 2 April 1882, illustrates the acceptance rate.[15] Of seventy-eight men responding, the First Council approved thirty-five for missions and rejected forty-three. The average age of nominees was forty-four. In this and other samplings, the main reasons why the council turned men down for missions were age, lack of finances, and personal matters the men themselves raised—debts, farming on shares, unable to support family, feeble health, supporting someone else on a mission, an ill relative, or no one to run the business or farm. Names approved by the council were forwarded to the Twelve, and the Twelve called some, rejected some, and ignored some, according to William Taylor:

It had been laid upon the First Council of Seventies to furnish missionaries from this body, but had not been able to respond to all the calls made upon them, which had given rise to some degree of censure. That many of the Seventies to whom they had written letters had been excused from taking missions, not being financially prepared, others through sickness and other causes. He thought it would be advisable to address a communication to the Presidency and the Twelve, that this matter might be laid before them.[16]

From 1880 to 1883, while the ward and stake system operated, the First Council tried to negotiate the restructuring and reviving of the official seventy six quorums. In November 1882, for example, President Horace Eldredge asked the First Presidency if the seventies should be consolidated from seventy six to fifty quorums, for which they had enough manpower or if the seventy-six units could be filled up? He also asked about filling up the First Quorum. No answers to his inquiries are recorded.[17] However, the First Council’s periodic pleas to reform the quorums caused the First Presidency to wrestle with the matter—preparation for the 1882 and 1883 revelations that brought solutions.

Revelation of 13 October 1882

The revelation John Taylor received on 13 October 1882 is best known for calling Heber J. Grant and George Teasdale to apostleships and Seymour B. Young, Joseph’s son, to replace Levi Hancock who died the previous June, leaving a presidency position vacant in the First Council. After Seymour Young became a polygamist, as requested by the revelation, the council had three youthful workhorses with their famous fathers’ surnames—Taylor, Cannon, and Young.[18]

Two lesser known parts of the revelation also affected the seventies. One part said the Twelve should “call to your aid any assistance that you may re quire from among the Seventies to assist you in your labors in introducing and maintaining the Gospel among the Lamanites throughout the land. And then let High Priests be selected, under the direction of the First Presidency, to preside over the various organizations that shall exist among this (Lamanite) people.”[19]

Leaders responded quickly to this command. Isaiah Coombs, a seventy in Payson heard about the Lamanite work in a November 1882 stake conference and commented in his diary:

Bro [George] Reynolds says this last Revelation marks a new epoch in our history. That was my view. It shows that the fulness of the Gentiles long looked for has come in, and that henceforth the burden of our labors will be directed to the House of Israel commencing with the Lamanites by whom we are surrounded and who manifest a great anxiety in the matter. Some of the Twelve are going out immediately among them and a majority of the quorum will move out in the same direction early in the Spring. The key is to be turned to that people by the Twelve, and the Seventies will follow up immediately to continue the work among them.[20]

President of the Twelve Wilford Woodruff told a Kaysville audience on 10 December 1882 that “we have now [after a half century of preaching to Gentiles] been commanded to turn to a branch of the house of Israel. Here are the Lamanites, thousands and thousands of them surrounding us. They look to us for the Gospel of Christ. It is our duty to go to them and organize them, and preach to them.” He added that “We (the Twelve Apostles, Seven ties and others) are called to go forth to preach the Gospel to the Lamanites and organize them. I am glad of it. I have felt for a long time that we should turn our attention to them.”[21]

In his 1883 diary, Apostle Franklin D. Richards traced the Twelve’s response to the Lamanite instruction. In a March meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve, he noted, “conversation turned on missionary labor among Indians.” In late April Apostle Teasdale reached Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Nation. By May plans were formulated to proselyte among the “Northern tribes of Indians.” Apostle Francis M. Lyman reached the Uintah Basin Indians by late May. “I feel awakened to get out among the Indians of the North,” Elder Richards confessed. By June plans called for Apostle Lorenzo Snow to visit the Shoshoni, Bannock, and Nez Perce Indians at Fort Hall, Idaho, and for Apostle Moses Thatcher to contact the Shoshonis and Crows in the Wind River Mountains. In July men left for the Crow reservation. On 31 October Apostle Teasdale reported on his Indian Territory mission.[22]

After initial enthusiasm among the Twelve, the missions received less attention, although its Committee on Indian Affairs was functioning five years later, in 1888. Available records do not indicate that the First Council or any sizeable group of seventies became part of the Lamanite missions as stipulated in the 1882 revelation.[23]

The 1882 revelation also commanded priesthood bearers and all members to “purify themselves” and to fully organize every priesthood quorum, and that leaders “inquire into the standing and fellowship of all my Holy Priesthood in their several Stakes.” It said for all “to repent of all their sins and shortcomings, of their covetousness and pride and self will, and of all their iniquities wherein they sin against me; and to seek with all humility to fulfill my law.” Heads of families were warned “to put their houses in order,” to “purify them selves before me,” and “to purge out iniquity from their households.”[24]

The reformation call received immediate response from the Saints, including seventies. At the biweekly general seventies meetings in Salt Lake City, speakers mentioned that the revelation made them introspective and repentant.[25] William Taylor reported 3 January 1883 that during his visit to stakes and wards he “found a general desire to improve” and “a feeling that the Seventies expect a chastisement if they do not repent of their pride, self will, and covetousness. Many of the brethren hold the revelations as a great blessing and are endeavoring to take a course that is acceptable to the Lord and feel the necessity of purifying themselves and of setting their families in order.”[26]

Leaders announced that purification meant, among other things, living the Word of Wisdom. First Council records show that there was definite need for Word of Wisdom adherence, particularly regarding alcohol. From 1879 to 1882 the First Council cracked down on some seventies who were habitually drunk, and on those who operated liquor stores. The council urged seventies in the wards to help the youth avoid the saloons. Word of Wisdom observance soon became a key part of the seventies’ reorganization program.[27]

Instruction and Revelation of 14 April 1883

The 1882 revelation instructed the Twelve to “assist in organizing the Seventies.” Subsequently, the Twelve and First Council talked, at least informally, about reorganization methods. On 13 April 1883 the First Presidency, the Twelve, and the First Council met together in President John Taylor’s office and discussed “the best method of filling up the quorums of the Seventies and of making the organization of the Seventies the most effective.” President Taylor started the meeting by defining the duties of seventies and of the First Council. Next, his counselor George Q. Cannon and apostles Woodruff, Richards, and Erastus Snow spoke on “the necessity of the quorums being fully organized and acting” in order. The frail Horace Eldredge was in California but Presidents Harriman, Gates, Taylor, Cannon, and Young were present. According to Seymour Young, the First Council “suggested plans where there were places to fill up in the quorums and of ordaining new members.” Attenders also discussed replacing John Van Cott who had died two months before. Apostle Richards called the session “a lengthy sitting, interesting, and satisfactory.”[28]

John Taylor adjourned the meeting until the next morning, Saturday, so he could take the matter “under advisement.” That afternoon, his First Council member-son William W. Taylor wrote out “father’s views on the organization of the Seventies. Bro. George Reynolds completed this labor and the document was then presented to and approved by his [John Taylor’s] counselors.”[29]

The next morning, Saturday, 14 April, the three groups met again at John Taylor’s office. First, George Reynolds read a set of instructions called “conclusions and directions of the Presidency as to method of reorganizing the Quorums of Seventies.” Then came a surprise. The brethren read “a Revelation given today [that morning] through Pres. John Taylor approving our con sideration and conclusion on this subject.” Thus the seventies and the Church received a two-part document that day: Instructions, and a Revelation sanctioning the Instructions.[30]

The Instructions first addressed the critical matter of recreating the First Quorum: “In the organization of these quorums in October, 1844, there were ten quorums, each provided with seven presidents, which presidents constituted the First Quorum of Seventies, and of which the First Seven Presidents of the Seventies were members, and over which they presided.” But because seventies had greatly increased, “these regulations will not apply to the present circumstances.” Further, although the First Quorum had not functioned since 1844, “it would seem there are duties devolving upon its members, as a quorum, that may require their official action.” A new method of filling the First Quorum was then explained: “The First Quorum of Seventies may be composed of the First Seven Presidents of the Seventies, and the senior presidents of the first sixty-four quorums. These may form the Seventy referred to [in] the Book of Doc trine and Covenants, and may act in an official capacity as the First Quorum of the Seventies.”

Senior presidents of other quorums beyond the first sixty-four “may meet with the First Quorum in their assemblies in any other than an official capacity.” When any First Quorum members are absent, presidents of other quo rums “can act in the place of such members with the First Quorum.”

The First Council finally had official clearance to refill their own quorum, but such action, of necessity, took a back seat to organizing the other quorums.

The Instructions, bearing the First Presidency’s signatures, ordered a badly needed reorganization of seventies quorums. It called for a geographical method of relocating and refilling existing seventies’ quorums: “The head quarters of the different quorums, and the records thereof, may be distributed throughout the various Wards and Stakes.” Such distribution should be based on “the number of the Priesthood residing in such locations.” Vacancies in the realigned quorums, either in presidency or membership, “can be filled by the ordination of persons residing in the locality” of each quorum. Men transfer ring to the realigned quorums must bring certificates of standing from the quorum they were leaving and a certificate “of good standing from the Bishop of the Ward to which they belong.” Problems about quorum presidents should be reported to the First Council “who may suspend such presidents, if their conduct seem to justify it, pending the actions of the First Quorum.” Seventies dropped from fellowship by quorums “should be reported to the High Council having jurisdiction.”

The second part of the document, the revelation, came in response to President John Taylor’s prayer, “Show unto us Thy will, O Lord, concerning the organization of the Seventies,” after presenting the Instructions before the Lord for confirmation or disapproval:

What ye have written is my will, and is acceptable unto me: and furthermore, Thus saith the Lord unto the First Presidency, unto the Twelve, unto the Seventies and unto all my holy Priesthood, let not your hearts be troubled, neither be ye concerned about the management and organization of my Church and Priesthood and the accomplishment of my work. Fear me and observe my laws and I will reveal unto you, from time to time, through the channels that I have appointed, everything that shall be necessary for the future development and perfection of my Church, for the adjustment and rolling forth of my kingdom, and for the building up and the establishment of my Zion. For ye are my Priesthood and I am your God. Even so. Amen.[31]

“These instructions have met our views,” said Seymour Young, “God is determined to have a people pure in heart.”[32] George Q. Cannon of the First Presidency felt “great joy and satisfaction,” adding that “he had for some years felt dissatisfied with the condition of the Seventies.” Apostle Richards observed that “the Lord has signified that he is pleased with their organization,” and said the labor now facing the seventies was “to gather up all who belong to these quorums and to “make a more formidable organization than has ever before been in the Church.”[33] Three thousand copies of the Revelation and Instructions were printed and distributed to seventies and stake leaders.[34]

Other council members were out of town so the three newest members, Presidents Taylor, Cannon, and Young, hammered out the nuts and bolts of the geographic restructurings and submitted a master plan to the Twelve. The trio developed four objectives: (1) to redistribute the quorums fairly evenly throughout the stakes, (2) to convince seventies to join the nearest quorum and to surrender memberships in quorums farther away, (3) to fill up quorums by transferring or newly ordaining seventies, and (4) to create new quorums in areas needing them. On 9 and 12 May the Twelve approved this plan.[35]

To redistribute quorums, the council calculated that seventies ought to be two-sevenths of any stake’s total Melchizedek Priesthood bearers. Using the two-sevenths yardstick, they figured out how many seventies and quorums each stake needed. Then the council identified which quorums were surplus and shuffled those units’ record books to stakes needing quorums. When possible, quorum headquarters were not moved. Between May and October 1883, the council visited stakes to move quorums and call presidencies where needed. Elder Gates helped reorganize and ordain in stakes south of Millard Stake, and President Eldredge, back from California, helped the trio reorganize the rest.[36]

Salt Lake Stake with 1100 seventies (one-fourth of the Church’s total) was headquarters for forty quorums (half the Church’s total). By ratio the stake deserved only seventeen quorums, so the council transferred out more than twenty quorum record books. Due to gaps in quorum records we can positively identify only ten of the transferred quorums. (See Table 2. [Editor’s Note: For Table 2, see PDF below, pp. 72–73]) Quorums remaining within the stake received fixed geographic boundaries that encompassed from one to a handful of wards, sometimes matching the boundaries of elders quorums created in 1877.[37]

Late in 1883 the council published an up-to-date list of every quorum, its senior president, and his address. At least fourteen headquarters had been moved.

With seventy-six quorums geographically located, the council next assigned seventies to local quorums. The local quorum presidency was assigned to preside over all seventies in their area whether they belonged to the local quorum or not so that “all Seventies will have someone to look after them and they can be conveniently reached.”[38] Newly ordained missionaries simply joined their closest quorum. Men belonging to an outside quorum were urged but not required to “join the Quorums where they are located.” The reorganized Twenty-first Quorum, which moved its headquarters and records from Fillmore to Scipio, illustrates how badly the geographic system was needed: the new members of the Scipio quorum had previously belonged to fifteen different quorums.[39] Some men found it hard to surrender their standings in their old quorums. Some regretted losing seniority in their old quorums.

Quorum presidents living away from their quorum headquarters were asked to surrender their presidencies and join the local quorums. Absentee presidents were termed “a detriment instead of an advantage” to their units. If such men insisted on keeping their original quorum memberships the men could “be retained as members of the Quorum only, and others be set apart to act as the presidents.” The council, when calling presidents for the revised quorums, tried to choose men who had been presidents in their previous quorums. The council also tried to call presidents from different wards encompassed by the quorum.[40]

Filling Quorums and Creating New Ones

The reorganized quorums had many vacancies. In September 1883 the First Presidency and the Twelve authorized the council to “adopt any method which in their wisdom they may think proper” to recruit new seventies.[41] One way was to round up unenrolled seventies living near a given quorum and enroll them. Then, elders were hand-picked to become seventies, elders who it was hoped met apostle Wilford Woodruff’s criteria that “every man ordained to the calling of “a Seventy should have heart, spirit and desire enough about him to go forth when called and to preach the Gospel among the nations, and without this spirit he should not be ordained.”[42]

Soon, “many young men were being ordained.” At Scipio, for example, twenty-seven elders joined the Twenty-first Quorum in 1883-84. Their average age was thirty-five. Presidents Cannon, Taylor, and Young traveled almost every Sunday in early 1884 to meet with seventies units, and they ordained twenty to forty new seventies each weekend. By April 1884, the council reported that the seventy-six quorums and presidencies were “nearly all filled up.” Only First Council members could set apart a senior president of a quorum, but other presidents could be set apart and new seventies ordained by the quorum’s senior president with the council’s permission.[43]

During the 1880s the cut-off age for missionaries dropped from fifty-five to forty-five. Some quorums, needing more potential missionaries, wanted to prune off elderly members. The First Council, lacking authority to make high priests of older seventies, discussed the problem with the First Presidency and then announced that old seventies “have the consent of the First Presidency . . . to be recommended to the High Priests Quorum.”[44] How many men were “promoted out” this way is not documented.

Once quorums were filled and officered, the First Council began creating new quorums where stakes needed them. Table 3 shows twenty-five new units created between 1884 and 1888. Elder George Q. Cannon noted in 1883 that seventies “would continue to increase until they would number one hundred and forty-four thousand . . . in fact there was no limit.” But by April 1888, after the 101st Quorum was formed, the Twelve ordered another moratorium “for the present” on ordinations except to fill vacancies.[45]

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3, see PDF below, p. 75]

Along with staffing and reorganizing work, the First Council also performed its normal supervisory functions, issued circular letters of instructions, visited stakes and, after 1884, communicated with some quorums by telephone. In 1884 the council created three large districts encompassing all the quorums: William Taylor supervised the First District with twenty-six quorums; Seymour B. Young the Second District with twenty-three; and Abraham Cannon the Third District with thirty-three. When Elder Taylor died suddenly in mid 1884, his supervisory role in the First District passed to newly ordained John Morgan. Each supervisor tried to visit the stakes in his district annually to hold seventies conferences. Their reports punctuate the council’s minutes after January 1884.[46]

In 1887 the First Council conducted a survey and found that the forty-four units responding averaged sixty-four men per unit, twenty-four in attendance at monthly quorum meetings, two theological classes per month, and three men on missions.[47]

Purifying the Seventies

The 1882 revelation also called for a purification, so the council added a reform campaign to the reorganizing movement. The purification vehicle proved to be the bishop’s recommend. Every seventy, even the council members, had to obtain and submit to his quorum president a certificate signed by his bishop verifying his standing in the Church.

A big hurdle for many was the stipulation that they must obey the Word of Wisdom, a law not strictly enforced in the past. At an 1883 Fillmore Stake conference Apostle Francis M. Lyman and First Council members William Taylor and Abraham Cannon called for men to be ordained as seventies. Each ward submitted names but “after a rigid examination in regard to keeping the Word of Wisdom and other duties, but few were found qualified.” By contrast, an early 1884 report for Kanab noted : “There has been a good reformation with the Seventies in regard to the Word of Wisdom.”[48]

William Taylor explained the new “get tough” policy on the Word of Wisdom as nothing really new. He said it came from Joseph Smith as counsel “but through the Prophet Brigham as a command” and that “the Presidency and the Twelve Apostles have agreed strictly to adhere to it. They have called upon the Presidencies of Stakes to keep it and to teach others.” A September 1886 circular from the First Council to all seventies reiterated the reform call voiced in the 1882 revelation: “We would meekly exhort you all to purify yourselves, and to labor to remove from your families everything that is contrary to the mind and will of God.”[49]

By October 1884 “hundreds” of seventies were dragging their feet about recommends. The council decided to set a final deadline of 1 April 1887 for men to turn in recommends. When deadline day came, the council announced that “justice demands immediate action” and ordered quorum presidents to “strike from your rolls the names of all who have failed to comply.” Such delinquents did not lose priesthood or ward fellowship but lost quorum membership and could not be readmitted without permission from the First Council. How many men were dropped from quorums is not known.[50]

By 1886 the question of how to treat Word of Wisdom backsliders arose. Should they be booted out of quorums? Should they make binding promises to conform? The First Council counselled quorum presidencies that it was unwise to be “too rigid in exacting covenants” and not right to “make them covenant to keep the Word of Wisdom.” A report late in 1890 about men added to the Fourth Quorum found that none used tobacco, some occasionally used beer, tea, and coffee, but by promising to do their best they became seventies anyway. In 1888 the council was asked if a quorum president should be “dealt with” if he persisted in using tobacco? The answer: “The line cannot be drawn at present.”[51]

Missionary Role

All this reorganizing, recruiting, and purifying activity had the primary purpose of producing more missionaries. By 1884 it was again Church policy that missionaries be ordained as seventies, so the seventies resumed their interrupted tradition of being the missionary force for the kingdom. The number of seventies serving missions after the 1883 reorganizings was almost double the number serving before the 1877 ban on ordaining new seventies.[52] (See Table 4.) The restructured quorums began paying transportation costs for their men called on missions, eliminating a $100 hurdle that stopped men before 1883. Also, quorums did a better job of helping families of men away on missions, thereby encouraging more men to go. By late 1885 the First Presidency urged stake presidents to set up 40- to 160-acre “missionary farms” in wards to help sustain missionaries’ families, an idea the First Council also endorsed.[53]

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4, see PDF below, p. 77]

To make seventies mission-ready, quorums held monthly or bi-monthly meetings for gospel study and teaching practice. Also, the council asked quo rums to hold noncompulsory theological classes in each ward. These could be special Sunday School classes or weeknight classes—”any course tending to exercise Seventies in their callings i[s] acceptable.” By 1886 some quorums sponsored from one to five theology classes each. Some quorums held weekly classes. These classes, which pioneered the priesthood study-class work of the next century, pursued both theology and nonreligious knowledge “in order that they may combat error upon scientific as well as religious grounds.” The First Council warned against in-class debates, “devil’s advocate” type representation, and doctrinal speculations.[54]

By late 1885 the First Presidency expressed its dissatisfaction about missionary results to the Twelve. Too many seventies were “so embarrassed by debt that they cannot go.” The apostles were asked to “exercise a supervisory care over these nominations . . . so that unworthy representatives of our cause shall not go out.”[55]

In the mid-1880s the First Council approved hundreds of men for mission calls, and by July 1887 reported to Apostle Richards that “under the blessings of the Lord we have been able to bring into a moderately complete state of organization the various quorums of the Seventies” and “we have succeeded in obtaining quite an extensive list of names of different nationalities who are well recommended by their respective bishops and co-laborers in the quorums. . . . We therefore respectfully submit the fact to you that we are now prepared, as we have ever tried to be in the past, to furnish you the names of any number of brethren you may require for missionary labor in any field. We have used the utmost care in the selecting of men for this service.”[56] But Apostle Richards disagreed, saying that the Twelve had “selected the most of the missionaries from the Quorum of Elders and quite frequently from the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association, and I may say with gratifying success.” The Missionary Committee, he said, would continue to use seventies’ nominations as but one of various pools of names. He then announced more rigid qualifications for missionaries and harder clearance procedures.[57]

Record Keeping and Finances

The 1883 reorderings gave a new start to quorum record keeping. “Every quorum should have a recordbook,” the council ordered, for minutes, for up-to date rosters, and for genealogical data on each member. In 1886 the council called for a correct and full genealogical report of the quorums, to be transcribed upon the general First Council records.[58]

In addition to bishops’ recommends, seventies were told to obtain a license. Applications for new seventies licenses needed the date of ordination of the applicant, the officiator’s name, and the signature of the quorum president and bishop. The Church Archive contains stub-book after stub-book of seventies licenses issued from 1884 to 1889 and after.[59]

Council members had no annual appropriation from the church to pay council or personal expenses. They were self-supporting, and some found it hard going. Just before he died, Joseph Young made a plea to his fellow seventies for help, telling how he had labored for fifty years to provide for himself and now could not. Levi Hancock, in need, received some aid from the Presiding Bishopric. Seymour Young, on a mission in 1886, asked for $500 and the council turned him down—they did not like the precedent. With quorums revitalized after 1883, the council requested each unit to submit $35 a month •— 50 cents per man—to a Seventies General Fund. The fund paid for the council’s clerk, travel, printing, and mailing. The hope was that the fund would grow large enough “to assist those who are suddenly called to take foreign missions.”[60]

The First Quorum

For a third of a century the Church had operated without a First Quorum of the Seventy. Why then did the First Council try to resurrect it in the 1880s? Records do not provide clear-cut answers, but they suggest four.

One possible reason, one that historians need to probe, is that President Brigham Young did not want a First Quorum, that during his presidency of the Church he vetoed the First Quorum’s resurrection, and that only after his death in 1877 was the First Quorum a discussable topic again.

Another reason, more substantiated, is that reorganizers of the seventies in the 1880s could not do their work without facing the First Quorum question head-on. To organize and fill all quorums but the first one, the one thought to be the most important, could not be done without debating that quorum’s theoretical and practical roles past, present, and future.

A third reason could be that the membership at large, knowing the aging First Council had called a handful of alternates to help it, wondered why the council did not revive its own quorum instead to help out.

A fourth reason could be that Joseph Young, aware that a revitalizing of seventies quorums was upcoming, felt inadequate to lead these anticipated, vigorous units. The First Council’s February 1880 minutes hint at this: “Br. Joseph Young said in relation to the Seven First Presidents presiding over all the quorums, that he was afraid of standing with his counselors and presiding over them.” The statement, made during a discussion of the First Quorum, suggests that Joseph believed the First Council was but a skeleton crew unable to man the seventies ship properly without the First Quorum. (However, this raises a question with an answer beyond the scope of this study—why Joseph did not keep the old First Quorum going after 1844.)[61]

“The Seventy,” the Doctrine and Covenants specifies, “form a quorum equal in authority to that of the Twelve” and can preside over the Church if the First Presidency and Twelve do not exist (D&C 107:24-26). Clearly, seventy-six or more quorums could not be “the Seventy” referred to. “The Seventy” apparently need to be an authority above the level of normal seventies quorums, and by general understanding a century ago “the Seventy” were to be the First Quorum. But who joins that quorum and how is it to be filled? During the 1880s three methods were considered: (1) the 1844 method, by which the seven presidents of quorums two through ten, when called together by the First Council, constituted “the Seventy”; (2) the method proposed by the 1883 Instruction by which the senior president of each of the next sixty three quorums, when called together by the council, were “the Seventy”; and (3) the First Council’s preferred method, the method by which the original First Quorum was filled in 1835, of calling sixty-three independent of their seventies quorum affiliation or office. Lack of consensus about which method to use was one of two major reasons why the First Quorum did not resurrect in the 1880s.

The second major reason seems to be that, although priesthood theory re quires a First Quorum, priesthood practice during that decade revealed no urgency for the quorum. “It would seem there are duties devolving upon its members, as a quorum,” the 1883 Instruction said, “that may require their official action.” But what kind of duties and action? The decade’s records pro vide few specifics except that “the Seventy” could hold trials for senior quorum presidents, receive reports, and conduct Seventies business—tasks that the council could easily handle anyway through existing apparatus.[62]

Three times the council had opportunities in the 1880s to resurrect the First Quorum and three times nothing happened. The first chance came in 1879-80. Late in 1879 the council discussed the desirability of filling the First Quorum but expressed uncertainty how to proceed. Joseph Young, either from historical amnesia or for personal or practical reasons, did not want to use the 1844 method of filling the quorum with presidencies of other quorums. Other leaders agreed. Council member John Van Cott, for example, “could not see any authority for Presidents of other Quorums being any part of the First Quorum.” Seymour B. Young “thought a man could not be President in two places at once.” “It was not by being in any particular Quorum that we receive any more authority,” Joseph Young explained, “but it is in the organization.”[63]

Early in 1880 Joseph asked for and received the Twelve’s permission to fill the First Quorum by transferring some of the Eighth Quorum into it and then filling vacancies in both quorums with new seventies. But the plan hit a snag. Elder William F. Cahoon, president of the Second Quorum, told Joseph that at the School of the Prophets in Kirtland Joseph Smith taught the 1844 method. Joseph Young said he had not known that before—evidently meaning he thought the 1844 idea was Brigham Young’s. Accepting Elder Cahoon’s testimony, Joseph Young decided that “when he called for a representation of the First Quorum he wanted the Presidency of the Second to the Tenth Quorums to rise.”[64]

But a month later the Council was balking at the 1844 method. Alternate Enoch Tripp “spoke of the importance of being governed by what is written in the Revelations. Thought there should be a full and sufficient Quorum comprising the First Presidents with the Presidents of nine Quorums. He wished to see this settled.” But Joseph Young decided “he would let everything rest as it was” because he wished to discuss the matter with the Twelve. He also consulted with old timers, including Harrison Burgess who also remembered Joseph Smith teaching the 1844 plan. Further, the council searched Church histories for items pertaining to the early seventies. Then the matter dropped, and the council did not tackle it again before Joseph Young died in 1881. In November 1882 President Eldredge asked the First Presidency about filling the quo rum but no approval came.[65]

The second chance to form the First Quorum came when the 1883 Instructions and ratifying revelation permitted the First Quorum to be filled by calling the next sixty-three quorums’ senior presidents. Obviously the First Quorum could not be filled by this method until the next sixty-three quorums had senior presidents properly installed. So Wilford Woodruff, president of the Twelve, instructed the council to organize and fill the existing quorums first before the First Quorum. The council obeyed. During the reorganizings, however, some senior presidents of quorums talked of sitting soon in the First Quorum. By late 1883 when the first sixty-four quorums had their senior president properly in stalled, the First Council could have called the First Quorum together but did not. From 1884 to 1888 the First Quorum topic appeared only once or twice in council minutes, and no action resulted. Perhaps the council was too busy filling old quorums and organizing new ones to tackle the First Quorum matter again.[66]

A third opportunity came in 1889-90. Jacob Gates, new senior president of the council, asked his colleagues to organize the First Quorum.[67] In response they drafted a letter to senior apostle Wilford Woodruff (the First Presidency was not yet organized after John Taylor’s death in 1887) explaining what problems the 1883 method would cause if implemented. Using the sixty-three quorums’ senior presidents, the council reasoned, would fill the First Quorum with many elderly men and many living far away from Salt Lake City. Instead, why not fill the First Quorum with individually selected men who were vigorous and who lived close to headquarters? The letter added that, whatever method the Twelve approved, the council wanted permission to assemble the First Quorum members at the next general conference.[68]

The council submitted the letter to the Twelve in early 1889. No answer is recorded in council minutes, but a council letter written half a century later records what happened to the proposal: “When attention was called to the fact that the First Quorum would be scattered all over, and many of its members advanced in years, [so] it would be impossible to function as a quorum, the President [Woodruff] stated ‘that we will do nothing with it for the present,’ and since then nothing has been done.”[69]

Millennialism

Joseph Smith said that if he lived to be eighty-five he would see the Savior come.[70] Based on that teaching, some Mormons, including seventies, thought the second coming would occur in 1890. While the seventies’ reorganizings, revelations, and purifyings were not explicitly linked to an 1890 second coming, seventies’ records contain occasional millennialistic sentiments. In April 1880, for example, President Joseph Young “said the signs of the times were ominous of a great crisis which were [sic] at our doors, indicating a great up heaving and the convulsions of nations, which showed the great necessity of the Seventies being prepared for any emergencies that may transpire and to hold themselves in reddiness for coming events.”[71] Joseph Young told a confidant, Edward Stevenson, that he expected to see the second coming because Joseph Smith had promised him he “would not sleep” before the coming of the Son of Man.[72] “There were quite a few among us who had but a slight conception of the magnitude of the work,” a seventy said in 1883; “as the idea is entertained by some that missionary work was drawing to a close.”[73]

For the most part, however, such expressions were quiet. The First Council’s own minutes during the 1880s, in fact, lack millennialistic fever. The most direct statement on the subject by a council member came in September of the suspected millennial year, 1890, when President Morgan squelched notions that some Seventies entertained:

John Morgan said there are likely to be many more quorums of 70s organized (there were now over 100), there are many erroneous notions entertained by the 70s in regard to preaching the Gospel, that their missions would necessarily be short; that the end is very near and the Elders about to be called home &c, but in such things they are mis taken, as the Gospel is to be preached to all nations and will necessarily take a long time; the work has hardly commenced. . . . not half the counties in the United States (Southern States especially) have ever heard the Gospel preached.[74]

The First Council as Subordinates

Scripture, including the 1882 and 1883 revelations, teaches that the First Council is subordinate to the Twelve and First Presidency. The council accepted that role but at times found it hard to wait for superiors to grant re quests or make decisions. Joseph Young, for example, felt in 1880 that part of their difficulties stemmed from underuse by senior apostle John Taylor and the Twelve: “If he would call upon us to rally our forces, we would try and be ready; and for his part he wished the Twelve to give us a fair trial, and we would call out missionaries, place our hands upon their heads and bless them.”[75]

The Twelve and/or First Presidency determined when to ordain more seventies and when to halt. They approved alternates and they released them. They approved the ward and stake seventies president experiment. They selected, rejected, or ignored men approved by the First Council for missions. They reviewed and approved the First Council’s plans in 1883 for reapportioning seventies quorums among the stakes. They chose not to involve the seventies in the Lamanite missionary work. They tabled the First Council’s 1889 proposal to recreate the First Quorum. The First Council readily acknowledged that they took “no important steps without applying to them [the Twelve and First Presidency] in all cases where necessary.”[76]

The First Council did exercise some nominating powers regarding new council members. When John Van Cott died, the First Presidency and Twelve asked the First Council to nominate a Scandinavian replacement. When President Eldredge died, the Twelve asked the council for nominees to replace him. Of the four they suggested, B. H. Roberts was chosen.[77]

According to seventies’ records, the First Council did not meet regularly with the Twelve. However, there was considerable correspondence between the two units and one-to-one contact between individual Council members and apostles. Seventies’ business reached the Twelve and First Presidency informally through William W. Taylor talking to his father, John Taylor, and Abraham H. Cannon talking to his father, George Q. Cannon.

Seventies: How Much Priesthood Authority?

Who has higher authority, a seventy or high priest? That was a troubling question before, during, and after the 1880s. Joseph Young strongly asserted that seventies held higher authority. When a high priest asked to become a seventy in the early 1880s, Joseph Young ordained him and placed him in the Eighth Quorum. Joseph Young also said it was wrong for seventies to become high priests when called into bishoprics. Had not Joseph Smith rebuked Hyrum Smith for ordaining a seventy a high priest? Had not Joseph Smith and Brig ham Young both taught that seventies were “Seventy Apostles” with full “keys, powers, and authority” of the apostleship “to order and set in order the Stakes of Zion, Bishops, Bishops Councillors and high councils?” To make seventies become high priests “was contrary to the teachings imparted to him by the Prophet Joseph Smith and his successor Brigham Young.” John Van Cott said Brigham once taught that a seventy called to a bishopric ought to be “set apart”—not ordained—to act as a high priest, “for they could act in any calling, and could still be special witnesses [Seventy Apostles].” As late as 1888 the Council, in a general epistle, said that men chosen for stake and ward presiding positions “are not required to be ordained High Priests against their choice.”

Joseph Young also believed that seventies ordained as high priests did not need to sever their membership ties with seventies quorums. John Van Cott agreed: “Brigham had said that we will take the Seventies back again” who became high priests. By late 1882 some men held dual memberships in both high prists and seventies quorums.[78]

During the 1880s several situations proved the high priests-seventies controversy was still alive. To illustrate, T. B. Lewis, sustained at October 1882 Conference to join the First Council, admitted he was a high priest and was not installed. Normally the First Council members were not allowed to ordain high priests, and in late 1887 when a council member helped an apostle ordain a high priest at a stake conference, others of the Twelve judged the action improper. On still another occasion apostles Moses Thatcher and Heber J. Grant ordained high priests leaving for missions to the office of seventy, and Abra ham H. Cannon, a new apostle and former First Council member, reacted:

“While I believe that a Seventy holds the higher office, there are some, even among the Twelve, who think a high priest is higher.” One such was new Church President Wilford Woodruff who late in 1889 “decided it improper to ordain a high priest to a seventy.” [79]

The Council maintained that seventies were general officers under its leadership and not stake officers like elders and high priests. But some bishops and stake officers disregarded the First Council and exercised local controls over seventies. Sometimes seventies were called into local positions and made high priests without informing seventies quorum presidents or the council. In a 25 July 1888 epistle the First Council criticized the practice: “It is a matter of regret that heretofore, Bishops of Wards and Presidents of Stakes have taken from the councils and the membership of these Quorums some of the best men to ordain them Bishops, Bishops Counselors, High Counselors, etc. without consulting the officers of the Quorums from which these men are taken.”[80] But two weeks later, either through ignorance of the council’s epistle or in deliberate confrontation, Apostle Francis M. Lyman ordained a seventies president a high priest without asking the First Council’s approval.[81]

The council also disliked reports that bishops ordered seventies to do things that were beyond a bishop’s jurisdiction. “A Bishop has no right to dictate Seventies in regard to their Quorum matters,” the council warned; the bishop “has no jurisdiction over Seventies to send them out to preach in other wards than where they reside.” But the council also recognized that bishops had the right to call on seventies to fill the office of “acting” elders, priests, teachers, deacons, or even doorkeepers.[82]

Polygamy and the Seventies

Polygamous seventies in the 1880s, like other Mormon polygamists, had to deal with the “Raid” and the “Underground.” As noted, Seymor B. Young added a second wife as ordered by the 1882 revelation before joining the First Council. All First Council members that decade were polygamists, though only B. H. Roberts went to jail for polygamy (a fine place to preach the gospel, he said). Seymour Young and Daniel Fjelsted “arranged” to go on foreign missions to avoid arrest. Of seventy-five senior presidents of the seventy-five seventies quorums in 1883, nine were imprisoned for polygamy, or one out of eight. Some men wrote to the council, asking for missions to avoid prison. Of the entire seventies’ membership, enough men faced arrest to prompt the First Council to ask quorums to aid families of seventies on the underground or in jail.[83]

During Test Oath struggles in Idaho, some Saints, including seventies, agreed to defend the Church by taking the oath, losing Church membership, and then voting in support of Church-favored candidates and issues. In February 1889, for example, the Fifty-second Quorum in Oneida Stake was in “a deplorable condition” because forty-three members had taken the test oath and lost their Church memberships.[84]

Church leaders used the reorganization movement to enforce the Word of Wisdom but not to increase plural marriages. Hundreds of men obtained worthiness recommends from their bishops and scores of men filled new seven man presidencies, but no instruction came from the First Presidency, and Twelve, or the First Council that these men needed to be polygamists. In fact, polygamists made poor “Minute Men” type missionaries because they had too many obligations. “It was not necessary to load ourselves up with large families,” Apostle Brigham Young, Jr., told seventies in 1883; “but that when through faith and prayer the Lord calls us to take another wife, it is our duty to do so.”[85]

However, the year before, the 1882 revelation had read, “It is not meet that men who will not abide my law [plural marriage] shall preside over my priesthood,” thus setting a leaders-to-be-polygamists standard that General Authorities tried to enforce. At the priesthood session of April Conference in 1884 criticism was voiced of David H. Peery because he had resigned his stake president’s calling rather than add a wife. In the same meeting stake presidents Lewis W. Shurtliff, William W. Cluff, and Abraham Hatch were warned that they were holding themselves and the Church back by not taking second wives. Accordingly, the First Council, when selecting new seventies quorum presidents after 1883, gave “preference to those who had embraced the law of celestial marriage.”[86]

Continuous Revelation and Priesthood

In the 1883 revelation, the Lord addressed conservative Saints bothered by changes in Church practice. Like an “elastic clause” in the priesthood constitution, the verse informed members that the Lord can make changes in his priesthood. Priesthood leaders, it said, are not to be troubled or concerned “about the management and organization of my Church and Priesthood” but instead should trust the appointed channels and expect through those channels necessary future adjustments. Similar expression of priesthood elasticity came when the First Council objected to seventies quorum presidents being taken into bishoprics without the First Council’s permission. Was not this wrong, the First Council asked the First Presidency. Presidents John Taylor and George Q. Cannon answered that it was discourteous but not wrong. Then they added: “While upon this subject, we may say that it is not wise to have cast iron rules by which to fetter the Priesthood. The Priesthood is a living, intelligent principle, and must necessarily have freedom to act as circumstances may dictate or require.”[87]

Conclusion

The 1880s represent a golden age for seventies work. Beginning the decade disorganized, depleted, and scattered, the seventies, responding eagerly to two “thus saith the Lord” type of revelations in 1882 and 1883, experienced a large-scale restructuring. No less than fourteen quorums were relocated, hundreds of seventies were changed in their quorum membership, twenty-five new quorums were created, and many new quorum presidencies were called. More seventies served missions, perhaps 100 more per year, than in the 1870s. Because the average age of men called on missions dropped from above age forty to about the mid-thirties during the decade, returned missionaries brought younger blood into the quorums. Younger replacements for First Council vacancies helped it be more vigorous in supervising the work of the quorums. Because seventies and quorums were easily locatable after 1883, communication between First Council and quorums improved greatly. Pride in being a seventy increased because two revelations specifically expressed divine aware ness of and approval of the seventies’ calling. When bishops’ recommends were required, many seventies made successful efforts to change, especially with regard to the newly enforced Word of Wisdom. Ward theology classes were started. Seventies’ record books received vital updatings. Had Joseph Young lived until 1890, his discouragement with the state of things in 1880 probably would have changed to rejoicings over what the decade had done for his seventies.

Despite the major work done on reorganizing the seventies in the 1880s, some fundamental priesthood problems outlasted the decade. One was the long-term debate about how much authority a seventy, especially a First Council member, held compared to a high priest. Also, the First Quorum’s resurrection was shelved.[88] The goal of the 1883 revelation and Instructions was to place the seventies quorums in “perfect working order.” But, ironically, the one matter left unperfected was the vacant First Quorum, the capstone quorum of the entire seventies organization. The long-standing expectation that seventies be missionary-producing quorums found only limited fulfillment: the quorums continued to be retirement places for returning missionaries more than productive training camps for future missionaries. The Lamanite missionary campaign involving the seventies, called for by the 1882 revelation, never materialized. Finally, by geographically distributing seventies quorums throughout the stakes, the 1883 reorganization moved the day a notch closer when seventies would become local officers supervised by stake presidents instead of general quorums supervised by the First Council.

[1] First Council of the Seventy, Minutes 1878-1897, 24 Jan. 1880, microfilm, Historical Department Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Minutes cited hereinafter as FCM: archives cited as LDS Church Archives.

[2] The two revelations are in James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1965), 2: 347-49, 352-54.

[3] For general histories of the seventies see S. Dilworth Young, “The Seventies: A Historical Perspective,” Ensign 6 (July 1976) : 14-21; and James N. Baumgarten, “The Role and Function of the Seventies in L.D.S. Church History” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1960). The unrecorded revelation is discussed in Joseph Smith, Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, B. H. Roberts, ed., 7 vols., 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Co., 1957), 2:182, 202; D&C 107:25, 26, 34, 38, 93-8.

[4] History of the Church, 2:221, 476; 7:305; Seventies Record Book B., 1844-48, Ms, LDS Church Archives, p. 31.

[5] Clark, Messages, 2:353.

[6] FCM, 1 Jan. 1881.

[7] William G. Hartley, “The Priesthood Reorganization of 1877: Brigham Young’s Last Achievement,” BYU Studies 20 (Fall 1979) : 34-35. Evidently Brigham Young asked the Twelve to not take seventies into bishoprics midway through the 1877 reorganizings, saying he was “tired of the egress and ingress” (turnover) of seventies, but was ignored, see FCM, 24 Jan. 1880.

[8] FCM, 13 Dec. 1879; First Council of the Seventy, Seventies General Meeting Minutes, 1879-1884, 16 March 1881, microfilm, LDS Church Archives, cited hereinafter as SGMM.

[9] FGM, 10 May 1879, 10 April 1880. Alternates were Edward Stevenson, Aurelius Miner, Enoch Tripp, [?] Ferguson, William Hawk, W. G. Phillips, John Pack, and William H. Sharp.

[10] FCM, 7 Sept. 1878; SGMM, 7 May 1879.

[11] SGMM, 2 June 1880; SGMM is a record of these meetings.

[12] FCM, 26 June and 25 Dec. and 27 Nov. 1880; 28 May 1881; 1 Sept. 1880.

[13] SGMM, 20 July and 3 Aug. 1881.

[14] FCM, 25 Dec. 1880.

[15] Ibid., 1 and 2 April 1882.

[16] Ibid., 11 March 1882.

[17] Ibid., 25 Nov. 1882.

[18] Clark, Messages, 2:348-349.

[19] Ibid. President Taylor submitted the revelation to the Twelve, the First Council, stake presidents, and others for approval: see John Taylor to Albert Carrington, 18 Oct. 1882, in Millennial Star 44 (13 Nov. 1882) : 732-33.

[20] Isaiah M. Coombs, Diary, 23 Nov. 1882, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives.

[21] Sermon by Wilford Woodruff at Kaysville, Utah, 10 Dec. 1882, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1854-86; reprint ed. 1967), 23:330-331.

[22] Franklin D. Richards, Journal, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives, 21 March, 11 and 15 April, 6 and 30 May, 6 June, 18 July, 31 Oct. 1883.

[23] Brigham Young, Jr., Journal, 20 Dec. 1888, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives.

[24] Clark, Messages, 2:348-9 .

[25] SGMM , 20 Dec . 1882.

[26] Ibid., 3 Jan. 1883.

[27] Brigham Young, Jr., Journal, 28 Sept. 1883; FCM 22 Nov. and 6 Dec. 1879; 23 Oct. 1880; 26 Nov., 3 and 31 Dec. 1881; 14 and 21 Jan., 11 Feb. and 25 March 1882; SGMM, 7 and 22 Dec. 1881, 4 and 18 Jan., 31 Dec. 1882; 7 Nov. 1883. One seventy visited several brothers in saloons “and found in one two hundred youths,” SGMM, 3 Nov. 1880.

[28] FCM , 6 Ma y 1883 ; William W. Taylor, Journal, 13 April 1883, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives; Franklin D. Richards, Journal, 13 April 1883; SGGM, 2 May 1883.

[29] FCM , 6 Ma y 1883; William W. Taylor, Journal, 13 April 1883.

[30] Franklin D. Richards, Journal, 14 April 1883; Clark, Messages, 2:352-54.

[31] Clark, Messages, 2:352-54 .

[32] SGMM, 2 Ma y 1883.

[33] Journal History of the Church, 21 April 1883, Ms., LDS Church Archives, account originally in the Ogden Daily Herald.

[34] FCM, 6 May 1883.

[35] Ibid., 9 and 12 May 1883.

[36] Ibid., 27 May 1883; Millennial Star 45 (9 July 1883) : 443 ; SGMM, 3 and 21 Oct., 22 May 1883; FCM, 8 June , 20 May 1883.

[37] Millennial Star 45 (9 July 1883) : 443; SGMM, 27 May 1883; Hartley, “Priesthood Reorganization of 1877,” p. 23; FCM, 12 Aug. 1882.

[38] Fourth Quorum of Seventies, Minutes, 12 J u n e 1883, microfilm, LD S Church Archives; First Council of the Seventy, Circular Letter, 22 Oct. 1884, LDS Church Historical Department Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, cited hereinafter as LDS Church Library; FCM, 11 June 1883.

[39] FCM, 27 May and 5 June 1883; “Record of the 21st Quorum of 70s” in Thomas Memmott, Journal, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives.

[40] FCM, 2 Dec. 1884; First Council of the Seventy, Circular Letter, 22 Oct. 1884, LDS Library; SGMM, 6 June 1883; Thomas Memmott Journal, 24 Jan. 1883; Thirty-third Quorum of Seventies, Minutes, 15 Jan. 1884, microfilm, LDS Church Archives.

[41] FCM, 2 Sept. 1883.

[42] Robert Campbell to William Hyde, 18 Jan. 1884, First Council of the Seventy, Letter press Copybooks, 1884—1909, film of holograph, LDS Church Archives, cited hereinafter as Council Copybook.

[43] FCM, 16 May 1883; SGMM, 17 Oct. 1883; Twenty-first Quorum Records in Mem mott, Journal; Council Copybook, 11 April 1884; FCM, 29 Sept. 1885.

[44] FCM, 29 Jan. 1884, 5 Jan. 1886, 1 Dec. 1889, 11 March 1882, and 31 Aug. 1887.

[45] Journal History, 22 April 1883, from the Ogden Daily Herald; Robert Campbell to Christian D. Fjeldsted, 19 April 1888, Council Copybook.

[46] FCM, 23 July and 22 Oct. and 24 June 1884, 9 March 1886; FCM for 1883-1890.

[47] FCM , 28 Dec . 1887.

[48] FCM , 28 Nov. 1883, 16 April 1884.

[49] SGMM , 21 Nov. 1883; FCM, 28 Nov. 1883, 29 Sept. 1886.

[50] FCM , 21 Oct. 1884, 15 Dec. 1886, 1 April 1887, 17 April 1889.

[51] FCM, 7 Jan. 1885, 2 June 1886; Fourth Quorum Minutes, 13 Oct. 1890; FGM, 1 Feb. 1888.

[52] FCM, 27 May 1883.

[53] After 1883 the reasons cited in F C M for m e n not being able to accept missions decreasingly included transportation expense; FCM, 25 July 1888.

[54] Thirty-third Quorum, Minutes, 18 April 1886; FCM, 9 March and 25 Jan. and 22 Feb. 1888.

[55] Clark, Messages, 3:42-43; FCM, 12 Nov. 1885.

[56] FCM, 20 July 1887.

[57] Ibid., 31 Aug. 1887.

[58] Ibid., 2 Dec. and 6 Nov. 1884.

[59] FCM, 2 Dec. 1884 and 16 May 1883; Seventies Ordination Certificate Stubs, 1839-1900, microfilm, LDS Library.

[60] First Council of the Seventy, Circular Letter, 10 March 1886, LDS Library; FCM, 14 July 1886; FCM, 1 May and 2 Oct. 1880 and 12 Feb. 1881.

[61] FCM, 28 Feb. 1880.

[62] Clark, Messages, 2:353 ; FCM , 16 M a y 1883.

[63] FCM, 13 March and 28 Feb. and 20 March 1880.

[64] Ibid., 22 Dec. 1879, 6 and 13 and 20 March 1880.

[65] Ibid., 17 April and 5 and 12 June 1880, 25 Nov. 1882.

[66] Ibid., 16 May and 7 Nov. 1883, 25 Aug. 1885.

[67] Ibid., 5 Dec. 1888.

[68] FCM, 12 Dec. 1888, contains the full text of the letter. Early in 1889, the letter was sent to the Twelve (ibid., 20 March 1889). The Twelve intimated they would meet with the First Council (ibid., 27 March 1889) to take action on the letter. That summer, Seymour B. Young consulted with the Twelve on the matter, but no results were recorded (ibid., 24 July 1889).

[69] Letter, no author, no addressee, no date, typescript, First Council of the Seventy, Out going Correspondence, 1939, L DS Church Archives.

[70] Alma P. Burton, comp., Discourses of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City, Utah : Deseret Book, 1977), p. 236.

[71] FCM , 17 April 1880.

[72] Edward Stevenson, Diary, 1878-81, microfilm of holograph, LDS Church Archives.

[73] SGMM , 23 Feb. 1883.

[74] Fourth Quorum, Minutes, 8 Sept. 1890.

[75] FGM, 24 April 1880.

[76] Robert Campbell to Henry Herriman, 27 Nov. 1884, Council Copybook.

[77] FCM , 30 April 1884, 30 Jun e 1883, 3 Oct. 1888.

[78] Ibid., 29 May 1880, 21 May 1881, 2 June 1880, 13 Dec. 1879, 29 May 1880, 2 April 1881, 25 July 1888, 1 Oct. 1882; SGMM, 19 May 1880.

[79] SGMM, 18 Oct. 1882; FGM, 30 Nov. 1887, 9 Oct. 1889.

[80] FCM, 25 July 1888.

[81] Ibid., 8 Aug. 1888, 8 Dec. 1886.

[82] Ibid., 8 Dec. 1886.

[83] Ibid., 11 Sept. 1889, 14 July and 20 Oct. 1886; statistics based on name matches be tween list of senior quorum presidents in 1883 and list of Mormons jailed for plural marriage reasons, contained in Andrew Jenson, “Prisoners for Conscience Sake,” manuscript, LDS Church Archives. Those jailed and their quorum numbers: Wm. H. Tovey (4), Charles Monk (19), George Reynolds (24), Edward Peay (34), John F. Dorius (47), Walter Wil cox (57), Hans P. Hansen (58), Thomas Barrett (67), and William Yates (68).

[84] Brigham H . Roberts, Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News Press, 1930), 6:213; FCM 13 Feb. and 20 March 1889.

[85] FCM , 27 May 1883.

[86] Clark, Messages, 2:348 ; Thomas Memmott, Journal, “Quotation Book,” pp . 102-4 (In section on plural marriage under heading called “Notes on remarks made in Priesthood meeting, General Conference, April 1884”).

[87] FCM, 15 Dec. 1886. The First Council did not always like the elastic approach, for the traditional view of seventies being seventy-apostles gave their quorums more importance. B. H. Roberts became a vocal, perhaps strident, traditionalist regarding seventies. In 1926 Apostle Rudger Clawson, on behalf of the Twelve, while criticizing Roberts for favoring previous revelations, wrote to President Heber J. Grant that previous revelations “must be construed with reference to the whole text of our law and the principles which control our government. In such a construction it will not be difficult to reconcile present practice or such further policies which may be adopted with the letter and spirit of the texts [of the revelations].” He added:

The doing of the work of the Lord must always be of chief concern. The whole organization of the Church is, in the last analysis, a facility, an agency for that high purpose. So that, while we do not desire to be understood to make an effort to minimize the value and importance of adhering to the general directions given in the revelations for the organization and maintenance of the quorums, we do express the firm conviction that these scriptural directions are, as herinbefore stated, subject to the interpretation of the inspired servants of the Lord who preside over the Church, whose interpretations will always be made with reference to the needs of the Church and the progress of the work.

Rudger Clawson to President Heber J. Grant, Extracts of Council of the Twelve Minutes and First Council of the Seventy, 1888-1941, 9 Dec. 1926, microfilm, LDS Archives.

[88] In October 1975 general conference, Church President Spencer W. Kimball announced the reconstitution of the First Quorum of the Seventy. Since then men have been called into the quorum without regard to previous seventies’ quorum affiliation or lack of it. In October 1976 general conference, all Assistants to the Twelve—high priests by ordination—were called into the First Quorum.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue