Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 4

A Ten-Year Kaleidoscope

The young son of one of my friends was recently heard to say, “Mormon women all look alike. They have pretty faces and good teeth and most of them are overweight.” Just a sea of faces—or bodies—as seen by someone who doesn’t know us and so doesn’t understand. Jan Shipps, a well-known non Mormon historian, has been studying Mormons for the past twenty years or so. She told me recently that she has experimented with so many different models in the attempt to understand that she has finally given up and decided that Mormons represent a unique system: she calls it a kaleidoscope. I think the image is a good one to apply to Mormon women—many-colored, shifting when you shake it, changing as you hold it to the light, yet keeping to a pattern. I too have been studying Mormon women in a way that leads me to paraphrase one of the teachings of Lowell L. Bennion, “The gospel of Jesus Christ is bigger than any one man’s perception of it.” I believe Mormon women are more diverse, more varied and more complicated than any one woman’s perception of them.

Ten years ago Dialogue published an issue on women edited by Claudia Bushman and Laurel Ulrich who went on from there to found a newspaper for Mormon women, Exponent II, and to publish a landmark collection of historical essays, Mormon Sisters. Since then both Claudia and Laurel have finished their PhDs, published books with national presses and obtained professorships at universities, while rearing a total of eleven children. With this anniversary issue they return, with a host of their sisters and some brothers, to help us look at the progress of the past decade.

In her introductory essay, Laurel reminisces about the burning issues of ten years ago and the difficulties in writing about them. She explains her own definition of “feminism,” a term that has become a hiss and a byword among many Mormons. She also makes the subject of priesthood come alive, a subject on the back burner when the first “pink” issue was published, but discussed here by two other scholars, Nadine Hansen and Anthony Hutch inson. Laurel’s essay builds a fitting bridge to other essays in theology, history and sociology, politics and the arts.

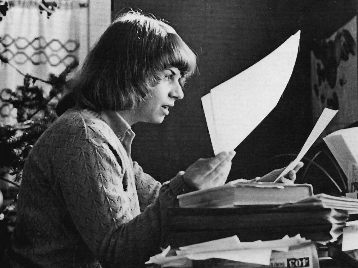

Ten years ago women were just beginning to find themselves through the arts; now many are established in visual, literary and kinetic forms—as shown by the paintings and drawings of Judith McConkie, the dance artistry of Maida Withers and the photographs of Robin Hammond. Linda Sillitoe and Meg Munk represent our ever-growing fictional prowess, while the continuing grace and strength of our poets is shown by Emma Lou Thayne, Loretta Sharp and Anita Tanner. The personal essay is becoming an art form, too, as women find their own voices, voices represented by Claudia Bushman, Eleanor Colton, the winners of the “Mormon Women Speak” essay contest, Ruth Furr’s Mother’s Day talk and our anonymous satire, “The Meeting.”

This women’s issue does not pretend to convey the total picture of the Mormon woman. As photographer Hammond puts it, “Beneath our Mormon facades we differ and agree in a multitude of ways.” The women represented here reflect not only their growing commitment to their arts and professions but their continuing loyalty to family, friends and religion. Their pilgrimage is a proud one, and they seek to share it with their brothers who need not fear to accompany them. Mormon women can be safely trusted and loved.

For every woman highlighted in these pages, a hundred others could have been chosen.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue