Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 3

The Fading of the Pharaoh’s Curse: The Decline and Fall of the Priesthood Ban Against Blacks

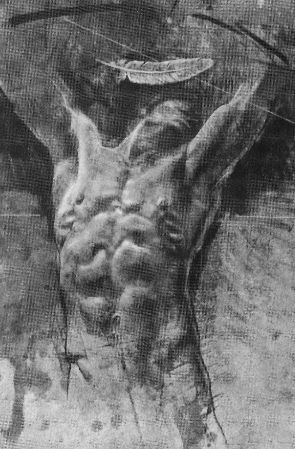

Now Pharaoh, being of that lineage by which he could not have the right of priesthood, notwithstanding . . . would fain claim it from Noah through Ham . . . [Noah] blessed him with the blessings of the earth, and . . . wisdom, but cursed him as pertaining to the priesthood.[1]

When President Spencer W. Kimball announced to the world on June 9,1978 a revelation making Mormons of all races eligible for the Priesthood, he ended a policy that for 130 years denied the priesthood to those having any black African ancestry. Now, just three years later—in a day when Eldredge Cleaver is talking about joining the Church—it is easy to forget the major changes that led to this momentous announcement.

The history of the policy of priesthood denial can, of course, be traced back to the middle of the last century; most Mormons have assumed that it is even older, much older, having been applied against the ancient Egyptian pharaohs. In this article I shall not be concerned with the full sweep of this history, on which a considerable body of scholarly literature already exists,[2] but rather with the final stage, or “decline and fall,” starting around the end of World War ll.

The first stirrings of this final stage might be seen in the 1947 exchange of letters between Professor Lowry Nelson, a distinguished Mormon sociologist, and the First Presidency of the Church.[3] The latter’s remarks to Nelson, who questioned the validity of church policy on race, are important because they were the first official (though not public) church utterance on the race subject for a long time. Following the traditional rationale, the Presidency explained the policy on blacks in terms of differential merit in the pre-mortal life; stated that the priesthood ban was official church policy from the days of Joseph Smith onward; and raised, with great misgivings, the specter of racial inter marriage.[4]

Two years later, the First Presidency issued its first general and public statement on the priesthood policy. This letter went beyond the earlier private one in its theological rationale, and included references to the black skin as indicating ancestry from Cain. It elaborated further upon the notion of differential merit in the pre-existence, and held out the prospect that the ban on blacks could be removed after everyone else had had a chance at the priesthood.[5] Apparently based upon The Way to Perfection, the 1931 distillation by Joseph Fielding Smith of the cumulative racial lore since Brigham Young, this well-known letter expressed the position held, with rare exception and certainly without embarrassment, by Mormon leaders until very recent times.[6] The durability of that position, however, was to prove more apparent than real.

Twenty Years of Tempest

The Gathering Clouds of the 1950s.

David O. McKay became President of the Church early in 1951. He was to preside over the stormiest two decades in the entire history of the Mormon black controversy. In retrospect, President McKay would seem to have been an almost inevitable harbinger of change, not only because of the civil rights movement emerging around him in the nation itself, but even more so because of his own personal values. As early as 1924, Apostle McKay had attacked anti-Negro prejudice and the “pseudo-Christians” who held it; and, in a widely republished personal letter written in 1947, he had shown himself remarkably free of the traditional notions about marks, curses, and the like, referring instead to faith in God’s eventual justice and mercy.[7] Close personal friends, as well as members of his own immediate family, have affirmed that from early in his presidency, McKay believed that the restrictions on blacks were based not on “doctrine” but on “practice.”[8] One might well take the inference from such statements, that he considered the way clear to a change in the policy by simple administrative fiat, rather than by special revelation. Why, if the reports of those close to him are true, no such change came during his administration remains one of the unanswered questions of this period.[9]

President McKay does, however, seem to have taken some initiatives to reduce the scope of the priesthood ban to more parsimonious dimensions, and concomitantly to expand the missionary work of the Church considerably among the darker-skinned peoples of the earth. These initiatives took two principal (and related) forms: (1) the transfer of entire categories of peoplefrom “suspect” to “clear” as far as lineage was concerned; and (2) the transfer, in individual cases, of the “burden of proof” of clear lineage from the candidate to his priesthood leaders (i.e., to the Church).

It is difficult to be certain just when the “burden of proof” was shifted, and the shift may well not have occurred at the same time everywhere in the Church. Until 1953, at least, it was apparently incumbent upon suspect candidates for the priesthood to clear themselves genealogically before they could be ordained or given temple recommends. This was certainly the case in places like South Africa and parts of Latin America, where the risk of black African ancestry was especially high.[10] Such a policy obviously would place many converts in a kind of “lineage limbo” until they could be “cleared,” and deny the Church the badly needed leadership contributions of these potential priesthood holders. It was just such a predicament that prompted President McKay to investigate the situation first-hand in a visit to the South Africa Mission early in 1954. Immediately after that visit, the burden of genealogical proof was shifted to the mission president and priesthood leaders in that mission.[11]

There is reason to believe that the visit and subsequent policy deliberations on South Africa provoked more than a passing concern on President McKay’s part over the broader implications of the traditional racial restrictions in a church increasingly committed to worldwide expansion. It was in the Spring of 1954, just after his return from South Africa, that President McKay had his long talk on this general subject with Sterling M. McMurrin, and at very nearly the same time, one of the Twelve reported that the racial policy was undergoing re-evaluation by the leadership of the Church.[12] Just how serious the deliberations of the General Authorities were at this time we are not yet in a position to know. Only a year later, however, during an extended visit to the South Pacific, President McKay faced the issue again in the case of Fiji, where emigre Tongans had settled in fairly large numbers and had intermarried to some extent with the native Fijians.

The Church had been inconsistent over the years in its policy toward Fijians, and as recently as 1953 the First Presidency defined them as ineligible for the priesthood. President McKay however, was convinced by his visit to Fiji, and by certain anthropological evidence, that the Fijians should be reclassified as Israelites. He subsequently issued a letter to that effect which not only removed the doubt hanging over the Polynesian converts of mixed blood in Fiji, but also opened up a new field for missionary work. In 1958, a large chapel was completed in Suva (Fiji), and the first Fijians received the priesthood.[13] The Negritos of the Philippines had been cleared much earlier, and the various New Guinea peoples were also ruled eligible for the priest hood in the McKay administration.[14] An important doctrinal implication of extending the priesthood to all such “Negro-looking” peoples was to emphasize that the critical criterion was not color per se, but lineage (from “Hamitic” Africa).[15]

The situation in Latin America was far more complicated, and nowhere were the complications more pervasive and vexing than in Brazil. Categorical clearances of this or that population group, as in Fiji or New Guinea, could not feasibly be made in Latin America, nor, in the absence of apartheid, could the “burden of proof” of clear lineage be transferred to the Church with as little relative risk as in South Africa. That transfer thus seems to have taken place somewhat later in Latin America than elsewhere.[16] The Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores had had few qualms about miscegenation; and countries like Brazil had had such an extensive admixture of both Indian and African Negro ancestry as to make any reliable lineage “clearance” a practical impossibility. This problem was well known to Church leaders and may have been a factor in the postponement of proselyting among the Portuguese speaking native populations in Brazil. Until World War II, proselyting in both Brazil and Argentina was directed largely at Germans and other European emigre peoples. The first converts in South America were actually Italians, though they were soon joined by equal numbers of Spanish-speaking converts in Argentina. However, in Brazil, where racial mixture was especially extensive, proselyting was mostly confined to Germans until the outbreak of war, when the Brazilian government outlawed German-language meetings and looked with suspicion on German-based organizations. Only then did the proselyting efforts of the Church shift to the Portuguese-speaking Brazilians.[17]

When proselyting finally began in earnest among the latter, strenuous efforts had to be made to identify, well before baptism, those converts who might be genealogically suspect. Such efforts included a special lesson for investigators, near the end of the standard lesson series, in which the topic of lineage and access to the priesthood was discussed in a larger doctrinal and historical context. Investigators were urged to look through family photo albums, often in the presence of the missionaries, for evidence of ancestors who might have shown indications of African ancestry. Similar “screening” efforts were employed in various other Latin American countries, and the lineage lesson developed in Brazil was widely adopted, with various local modifications, in several Latin American missions.[18] The mission presidents, however, were given a great deal of autonomy by the General Authorities in the application of the priesthood ban to specific cases.[19]

It is not difficult to imagine the potential for grief that would follow such screening policies, the more so because of their ultimate operational futility. To make matters worse, there was considerable variation among mission presidents in how meticulously the screening was enforced, so that even in the same mission an incoming president of conservative bent might inherit from his more liberal predecessor a number of problematic cases of priests or elders of obviously suspect lineage.[20] Even with bona fide screening efforts of the most meticulous kind by all parties concerned, there was a constant potential for post hoc discoveries of ineligible lineage as the Saints in Brazil and elsewhere took seriously their genealogical obligations. When such discoveries were made, the mission presidents again had a great deal of autonomy in deciding how they were to be resolved, or whether they had to be referred to the General Authorities for resolution.

These resolutions themselves tended to have an inconsistent, ad hoc quality from one time or mission to another. Sometimes there really was no resolution; the case was either ignored or treated with benign procrastination. In other cases, the hapless holders of both Hamite lineage and priesthood office were notified that their right to exercise the priesthood had been “suspended” (or some synonym thereof). An intermediate resolution in some cases was to “suspend” an elder for all formal ecclesiastical purposes, but permit him to continue his exercise of the priesthood within his own home (including administrations to the sick).[21] With the eventual transfer, by I960, of the burden of genealogical proof from the Saints and investigators to missionaries and priesthood leaders, the incidence of post hoc discovery greatly increased. Nevertheless, the missionary harvest in Latin America only grew more bountiful than ever. Meanwhile, in North America itself, a number of cases long awaiting ordination or temple privileges were cleared under President McKay’s new policy on burden of proof.[22]

All such deliberations, adaptations and reformulations of the church racial policy during the 1950s remained unobserved by the membership and public at large, of course. Dr. Lowry Nelson, apparently not satisfied with the outcome of his earlier correspondence with the First Presidency, went public in 1952 with an article in The Nation that reiterated some of the thoughts he had expressed in his 1947 letter.[23] Having earlier responded to Nelson and others, however, the presiding brethren remained largely aloof from public controversy. A few General Authorities and other well-intentioned brethren attempted during these years to offer their own explanations and interpretations of Church doctrines and policies on race, primarily for internal consumption.[24] On the whole, the statements by church leaders in this period, like their less public struggles over policy applications, showed a certain consistency with the traditional and operative lore of the times, including a special concern for the problems presented by intermarriage.[25] Outside the Church, meanwhile, the nation itself was just beginning to discover its own racial problems and as yet paid little attention to the Mormons. Indeed, as late as 1957, when Thomas F. O’Dea published his insightful sociological study, The Mormons, he saw no reason to mention Mormonism’s “Negro problem,” even in his section on “Sources of Strain and Conflict.”[26]

The Stormy Sixties

Like most Americans, Mormons were somewhat taken by surprise at the civil rights movement. Treating blacks “differently” had become so thoroughly normative in the nation that even the churches generally did not question it until the 1950s, at the earliest.[27] Prior to that time, the public schools, the military, and nearly all major institutions of the nation were racially segregated. Accordingly, rumblings about racism among the Mormons were rare, and continued so until the 1960s.

The arrival of the New Frontier, however, was accompanied by an accelerating, and increasingly successful, civil rights movement, which not only produced a long series of local, state and federal anti-discrimination edicts, but which also rendered increasingly untenable and ridiculous a number of traditional racial ideas held by Mormons and others. The racial policy of the Church was soon attacked by spokesmen of liberal Christianity, who at length had discovered racism in the land;[28] it was attacked by the Utah branch of the NAACP;[29] it was attacked by important and nationally syndicated journalists;[30] and it was even attacked publicly by certain prominent Mormons.[31] Other internal critics, while agreeing with the official church stance that revelation was the only legitimate vehicle for change, still questioned the historical basis for the priesthood ban against the blacks, and especially the folklore that had traditionally been marshalled to support it.[32]

As external criticism grew, the reaction among the Saints was one of uncertainty and some dismay. Cherishing a heritage of persecution and discrimination of their own, Mormons (like Jews) had never been accustomed to thinking of themselves as the offenders in matters of civil rights. Yet church leaders and spokesmen actually had very little to say to their critics. When they responded at all, they fell back on a formal and legalistic position: However unpopular the Mormon policy might be in the rest of the nation, it was nobody else’s business, for it was an internal ecclesiastical matter. It was not a civil rights issue, because it had nothing to do with constitutional guarantees of secular, civil equality. Since non-Mormons did not agree that the Mormon priesthood was the exclusively valid one anyway, why did they care who got to hold it? Nor were Mormon blacks complaining. Thus, the continued harrassment of the Mormon Church over its priesthood policies actually constituted interference and infringement, under the First Amendment, of the civil rights of Mormons.[33]

To say that the world did not accept the Mormon definition of the situation would be a bit of an understatement. The America of the 1960s was not the place or time to try to convince anyone that any aspect of race relations was purely a private matter. The cacaphony of criticism and recrimination directed against the Church intensified steadily and finally spent itself, only at the end of the decade, in a great crescendo. As the decade started, George Romney’s 1962 gubernatorial campaign in Michigan gave critics in the media and in the civil rights movement a handy and legitimate occasion to raise questions about the carry-over of racist religious doctrines into political behavior. However, Romney’s terms as governor were so progressive in civil rights matters that the issue was left dormant. It arose again during the 1968 presidential primaries, but this time Romney’s campaign was aborted early, in part, some have claimed, to avoid putting any more pressure on the Church.[34]

The Utah chapters of the NAACP played a conspicuous role in the public pressures felt by the Church during these years. A plan for demonstrations at Temple Square during the October, 1963, General Conference, was called off only after private negotiations between President Hugh B. Brown and local NAACP representatives. President Brown’s unequivocal statement in advocacy of civil rights, at the opening Sunday session of the conference, was apparently one outcome of these negotiations.[35] Similar statements, repeated at subsequent conferences or other public occasions, did not long suffice, however, to dampen the NAACP animus. Under its auspices, pickets marched through downtown Salt Lake City to the old Church Office Building in early 1965 to demand church support for civil rights measures pending in the state legislature; and later in the same year the Ogden and Salt Lake Branches of the NAACP introduced a resolution at the organization’s national meeting strongly condemning the Church, and calling, in particular, for Third World countries to deny visas to Mormon missionaries.[36]

One such country, Nigeria, had already anticipated the NAACP call. The emergence of the Nigeria story in the midst of all the bad publicity of the time introduced an incredibly ironic note. In response to initiatives from interested Nigerians, dating back as far as 1946, the Church had been sending literature and exchanging letters, without much enthusiasm, until 1959, when a representative from Salt Lake City was sent to evaluate the situation. It was discovered that certain self-converted Nigerians had organized branches of the Church on their own authority and had thereby generated a pool of potential Mormon converts amounting to several thousands. Early in 1963, half a dozen missionaries were set apart for service in Nigeria that would have included not only proselyting, but also the construction and operation of schools and hospitals—then an unprecedented aspect of Mormon missionary work. Before the missionaries could be dispatched, however, the Nigerian government got wind of the traditional racial doctrines and policies of the Church and refused to grant visas. Negotiations over the matter between the government and the Church continued for several years but came to naught as the outbreak of civil war in Nigeria rendered the issue moot for the time being.[37] The ironic emergence and outcome of these developments, however, should not distract us from the more important point that the commitments made by the Church under President McKay to a country in Black Africa represented a distinct softening of the traditional policy of non-proselytization in such countries.

The Nigerian developments again occasioned some serious deliberations among the First Presidency in 1962 and 1963 over the feasibility of dropping, at least partially, the ban against blacks in the priesthood. President Brown, then second counselor, urged on his two colleagues that the traditional policy be modified to grant blacks at least the Aaronic Priesthood, pointing to the sudden need for local leadership that had developed in Nigeria. President Moyle, then first counselor, approved of this idea. So did President McKay himself, in principle, though he had qualms that such a piecemeal change might only exacerbate the already serious problem of intermarriage in various places.[38] For whatever reasons, these deliberations did not produce a policy change at that time, but they may well have been the basis for the optimism about change that President Brown expressed publicly on more than one occasion in 1963.[39] On the other hand, President McKay’s own expressed pessimism a year later may have been a reflection of a more realistic awareness on his part of the opposition to policy change that still obtained among some of the Twelve. A hint of that opposition surfaced very briefly around General Conference time in April, 1965, when President Brown and Elder Benson were found to be in public disagreement.[40]

On an official level, though, the presiding brethren seemed at least to stand together on the declarations in President Brown’s 1963 General Conference statement. That statement, of course, did not even mention the church priesthood policy; it simply upheld the emergent civil rights doctrine of the nation. Critics both in and out of the Church seemed unwilling to let the brethren off that easily. As the decade drew to a close, the Church was forced to fend off more serious attacks, first on the Book of Abraham (the only scriptural precedent for priesthood denial), and then on Brigham Young University (cf. below). During this period, President Brown moved once again for an administrative decision to drop the priesthood ban. Presumably he was joined by President Tanner, his nephew and colleague in the First Presidency. Throughout the latter part of 1969, Brown strove vigorously to win the concurrence of President McKay, whom he knew to share his view that the priesthood ban could properly be ended administratively. However, McKay was by then fading fast toward his death the next January, and he was not often physically capable of sustained deliberations. The decision making process this time was complicated not only by President McKay’s condition, but also by the fact that the First Presidency had by that time temporarily acquired five counselors, rather than the usual two.[41]

While we cannot be sure just how much resistance President Brown encountered among the rest of the General Authorities, the other counselors in the First Presidency at that time were Joseph Fielding Smith, Alvin R. Dyer, and Harold B. Lee, all of whom were on record with conservative views on the race question.[42] In any case, the public statement that ultimately issued from all these deliberations was not an announcement of an end to the priesthood ban against blacks, as Presidents Brown and Tanner had proposed, but rather the letter of December 15, 1969, which, while promising eventual change, actually only reaffirmed the traditional policy.[43] As in 1963, President Brown may have allowed his optimism during the deliberations to spill over into his public utterances, for he was widely quoted in the press during December, 1969, as making intimations of imminent change.[44] The change was not yet to come, however, and President McKay died on January 18, 1970, thereby dissolving the entire First Presidency. A week later, the new President of the Church, Joseph Fielding Smith, assured the world at a formal news conference that his views on church policy and doctrine had “never been altered,” and that no changes should be expected.[45]

Anticlimatic as this episode may seem, it would be a mistake to overlook the significance of the document it produced. The December, 1969, statement of the First Presidency (signed only by Presidents Brown and Tanner “for” the First Presidency), dealt with the theological basis of the priesthood ban for the first time in twenty years. This portion of the statement is notable for its parsimony: While referring back vaguely to a pre-mortal life, it said nothing about that life, nothing about the War in Heaven, or about any differential merit having implications for mortality. It said nothing about Cain or Ham or marks or curses or perpetual servitude. It relied almost entirely on the simple claim that the Church had barred Negroes from the priesthood since its earliest days ” . . . for reasons which we believe are known to God, but which He has not made fully known to man.” Thus, in its first official statement on the controversy in nearly a generation, the Church chose to set aside almost the entire doctrinal scaffolding that had bolstered its priesthood policy toward blacks for more than a century.[46]

The last doctrinal resort, presumably in support of the traditional priesthood ban, was the Book of Abraham, which contained the only passage in all of Mormon scripture relating explicitly to a lineage denied access to the priesthood: “the Pharaohs’ curse,” as it were. The acquisition by the Church, late in 1967, of a critical fragment from the papyrus upon which Joseph Smith had based his translation of the Book of Abraham, gave rise to a vigorous controversy, starting in 1968, over the authenticity of the translation. Though the various partisans in the controversy spent their ammunition in rather a short period of time, there was never a conclusive resolution, except for a general agreement that Joseph Smith’s rendering of at least the fragments in question had not been even approximately a literal one. While such a disclosure might seem to impeach the doctrinal authenticity of “the Pharaohs’ curse,” there is as yet no reason to believe that it affected the thinking of President Brown or any of his colleagues. Indeed, it seems rather surprising in retrospect that the implications of the Book of Abraham controversy for the traditional priesthood policy entered only occasionally and peripherally into the literature of that controversy, which seemed almost totally preoccupied instead with the more fundamental issue of Joseph Smith’s claims to the gift of translation, and to the prophetic mantle more generally.[47]

As the end of the decade approached, the Church was beginning to appear unassailable and impervious to all forms of outside pressure. The priesthood policy on blacks could not be changed, it was repeatedly explained, without a revelation from the Lord, and it began to appear that the greater the outside clamor for change, the less likely would be the revelation. Then the civil rights movement found a vulnerable secondary target. Brigham Young University began late in 1968 to encounter increasingly hostile demonstrations during athletic contests, chiefly in Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona and California. At least two prestigious universities, Stanford and the University of Washington, severed athletic relations with BYU altogether amidst much publicity and controversy, even though investigations by both the Western Athletic Conference and a University of Arizona delegation had exonerated the Mormon school of any discriminatory practices.[48] It soon became clear that this treatment of its showplace University, whether fair or not, had struck a sensitive Mormon nerve, and the Church began to fight back as it had never done while the issue was strictly an ecclesiastical or theological one. In a rare counterattack, evidently intended to forestall the rupture in athletic relations with the University of Washington, BYU President Ernest L. Wilkinson (doubtless with the approval of Church authorities) placed a full-page ad in major Washington newspapers on April 1, 1970. Entitled, “Minorities, Civil Rights, and BYU,” the advertisement strikes one as a very persuasive (if futile) public relations piece.[49]

Concomitant with the campaign against BYU, and probably stimulated by it, was the rise of a brief spell of collective jitters in Utah (mainly Salt Lake City) over rumors of impending black “invasions” and violence. It is difficult to assess the magnitude or intensity of this episode. Some people apparently acquired a kind of “siege mentality” as the public campaign against the Church and BYU intensified during the late 1960s. This mentality expressed itself in a number of ways: vigilante-type groups, called “Neighborhood Emergency Teams” (NETs) were formed in some areas for the “protection” of the citizens from the expected black onslaught;[50] a folk prophecy attributed to John Taylor, which predicted open warfare and bloodshed in the city streets, was retrieved and reinterpreted to give credence to current rumors; humor at the expense of blacks apparently became more common and more vicious; and rumors were circulated about attacks by blacks, in California and elsewhere, on the occupants of cars with Utah license plates.[51] White mob action, ironically, must have seemed for a time a more realistic prospect in Utah than black mobs ever were!

It is difficult to know how much exaggeration went into accounts of this period by the press and other observers. A Louis Harris poll taken in Utah during 1971, however, found Mormons far more likely than others in the state to give some credence to the existence of “a black conspiracy to destroy the Mormon Church.”[52] One apostle during this period privately expressed fear for the physical safety of church leaders, and another was already well known to have tied the civil rights movement to the international communist conspiracy.[53] Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that both church authorities and civil authorities actively opposed the incipient vigilantism of that hectic time, and it did not last long.[54] Nor is there reason to believe that it had much effect on the Saints outside Utah. While it surely must be counted as a troubling and embarrassing episode in Mormon-black relations, it does seem to have been limited in time and scope, so one must be cautious in attributing to it any general significance for “the Church” or for “the Mormons.”[55]

It is ironic that the “twenty years of tempest” just recounted coincided almost exactly with the presidency of David O. McKay. It is difficult to think of a president in the history of Mormonism who more personified the very antitheses of racism and social conflict; yet these will always stand as the traits that most marked his regime to the outside world. The storm began largely unnoticed behind a mountain range of ecclesiastical privacy, as President McKay and his colleagues struggled with the implications of adapting race policies developed in the isolation of Utah to the anomalies of exotic places. However expedient those adaptations may have seemed at the time, they were to prove ultimately unsatisfactory, not only in far off places, but in North America, as well.[56]

The national civil rights movement soon blew the storm out into the plains of public visibility and scrutiny. There it buffeted the brethren with blasts in the media from all quarters, including Nigeria; with pickets, protests, and political pressure; with assaults on BYU and the Book of Abraham; and ultimately with a vexing outbreak of mob mentality among the faithful in the heartland. Then, as unexpectedly as it has arisen, the worst of the storm seemed to die with President McKay in early 1970. By the end of Spring that year, nothing more was heard from pickets, protestors, vigilantes, or athletic disruptions. Through it all, the maddening Mormon policy on blacks had stood unchanged. Or had it? A closer look reveals that the policy had been stripped to its bare bones, both theologically and operationally. More change was yet to come.

Respite, Reconciliation, and Revelation

The outstanding developments of the 1970s were the respite granted the Mormon Church over the race issue by its critics, black and white; the reconciliation between the church and the blacks, in particular; and the revelation, late in the decade, ending the discriminatory ban. The civil rights movement in the surrounding society had begun to peak. A less supportive national government had come to power, many of the movement’s objectives seemed to have been accomplished and other minorities were now laying claim to some of what the blacks had won for themselves. Accordingly, critics inside and outside the Church backed off noticeably. It was as though they had all decided to give up on the obstinate Mormons and concentrate on other violations of the national equalitarian ethos (one of which, the women’s issue, would soon be haunting the Mormons).

A New Sensitivity

When Joseph Fielding Smith succeeded David O. McKay as President of the Church, there was some speculation about the presumably reactionary stance that he might take on racial matters. However, the aged incoming president never publicly reiterated the ideas he had expressed in his more vigorous years. Indeed, in several ways the Church began during his administration to show increasing awareness and sensitivity about race relations generally and relations with blacks in particular.[57] In late 1972, for example, when the Church was preparing to construct its new high-rise center in New York City, black residents of the area, and black members of the city planning commission, objected to the construction on the grounds that it would serve as a symbol of racism in an otherwise integrated neighborhood. The Church responded with public assurances about its planned relationships with the neighborhood, even offering to compensate a local black resident who felt that the value of his property had been somewhat compromised, and gave guarantees of non-discriminatory employment practices on the construction site. Black opposition thereupon faded rapidly.[58]

Not all such confrontations were so amicably settled. A scheduled tour of the Tabernacle Choir to New England in 1974 had to be cancelled because of protests from black clergymen in the region.[59] In the same year, the Church inadvertently ran afoul of the Boy Scouts of America through a new organizational arrangement that had the effect of integrating its scout troops more closely with the Aaronic Priesthood groups. The Church and the BSA had earlier agreed on this change, but neither had anticipated the barring of black youths from positions of scout leadership in Mormon troops. (Actually, all non-Mormons in those troops were also barred.) The Church was soon confronted by an NAACP suit over the matter, and corrective action was very fast in coming.[60] The Church clearly was more responsive now.

At the same time, however, the Church was as insistent as ever that policy change relating to the priesthood itself would still have to come through legitimate channels, and it tolerated little dissent from the inside over this issue. Two active (and theretofore loyal) brethren attracted considerable publicity, one in 1976 and the other in 1977, through certain dramatic gestures of dissent; both were promptly excommunicated for their efforts.[61] Toward the outside, though, there seemed to be an increasingly conciliatory posture on racial matters. It was as though, with the pressure off, the Church could afford to be less defensive about the integrity of its procedures for legitimate change.

A New Look in Public Relations

Much of the Church’s more amicable relationship with the outside world during the 1970s may have been attributable to the initiative of the new Public Communications Department, formed in August, 1972, with Wendell J. Ashton as its first Managing Director. Of course, the Church had had public relations efforts before: There had been a Church Information Service and a Press Secretary; and for special public relations projects, a professional firm would be retained. The new PCD, however, was an all-purpose, comprehensive, integrated public relations arm of the Church, with seven separate divisions staffed mainly by professionals, and with literally thousands of representatives located in the stakes and missions.[62] One of its earliest division heads (and now PCD Managing Director) was Heber G. Wolsey, who had been in charge of public relations at BYU during the sensitive time there a couple of years earlier.[63] One of the missions specifically assigned to the PCD from the beginning was “improving the image of the Church.” This was to be done, furthermore, not merely by reacting to criticism from the outside (the usual policy in the past), but by taking the initiative at given opportunities.[64]

In line with this new public relations enterprise and policy, Wendell Ashton himself began to appear on the national media (e.g., an NBC Special Report in 1973) and to field in a low key, but sophisticated way some tough questions on the race policy and other matters.[65] The more embarrassing (from a PR standpoint) doctrinal baggage omitted in the 1969 First Presidency statement remained firmly out of the public arena. It was the PCD itself, furthermore, that arranged for President Kimball to appear on NBC’s morning Today Show in 1974, where again he was faced with some rather blunt questions on the race policy, women’s roles and the family.[66] Whether entirely through PCD initiatives or not, the public image of the Church by the mid 1970s had greatly improved compared to a decade earlier. Criticism on the black issue, in particular, was far less frequent. The polemics of the sixties were replaced with more restrained and informed critiques.[67]

Black and Delightsome?

Nowhere was this new relaxed public relations posture more evident that in Mormon initiatives toward blacks during the 1970s. In retrospect, it seems clear that the Church, near the beginning of the decade, launched a deliberate and sustained campaign to build bridges with blacks, both inside and outside the Church. If it was not yet ready to end the priesthood ban, it at least felt the need to come to know more blacks better, and to remove the aura of “the cursed” or “the forbidden” that had accumulated in the consciousness of most white Mormons. It is scarcely possible for outsiders to appreciate the fundamental significance of this development, however gradually it may have occurred; it was, indeed, second in significance only to the later bestowal of the priesthood itself.

A few examples will suffice: Significant efforts to cultivate ties with outside blacks seem to have centered largely on BYU. During the 1969-70 controversy over BYU’s athletic ties with other schools, it was already apparent that the Mormon university was recruiting black athletes, many of whom were put in a very difficult position by the hostile pressures from the other schools, and from the black community more generally.[68] Nevertheless, the recruiting efforts continued, eventually bringing several black athletes to BYU, some Mormon and some not, and most on athletic scholarships.[69] Nor were BYU’s efforts all athletic. During the summer of 1971, a black man and wife from Los Angeles were both presented with doctoral degrees from the BYU College of Education.[70] In March, 1976, BYU students elected their first black student body vice-president.[71] In 1977, the renowned author of Roots, Alex Haley, was a commencement speaker at BYU, and in early 1978, Senator Edward Brooke was a special speaker at the University on the subject of relations with South Africa. During his speech (obviously well researched for a Mormon audience), the Senator digressed extensively toward the end for a discussion of Mormon-black relationships in the United States. His comments were remarkable partly for the candor which he felt free to use in reference to the Mormon position on blacks, but mainly for the conciliatory tone which provided the context for that candor. This was all in stark contrast to the hostile terms, and the demands for immediate policy change, which had characterized the comments of the Utah NAACP in 1965, or the Black Student Union indictment of BYU in 1969-70.[72] Even off campus, BYU students participated significantly in such things as fund-raising activities for black churches in Salt Lake City, thereby earning the appreciation of a prominent black minister, who, while clearly expressing his disagreement with the Church’s teachings, was nevertheless ” . . . glad that we could get together to show people that we’re not going to kill one another about it.[73]

Perhaps even more remarkable, however, was the new Mormon stance toward its own blacks. After more than a century of having been nearly “invisible,” Mormon blacks began to receive attention and promotional coverage in church publications and social circles. The Church News had ignored almost entirely things black (or Negro) until 1969. The Index to the Church News for the period 1961-1970 shows only one listing on the topic from July of 1962 to January of 1969, but several a year thereafter. Black singers began to appear with increasing frequency in the Tabernacle Choir, and one of these, a recently-converted contralto, was also appointed to the BYU faculty.[74] Feature articles about Mormon blacks began to appear in Church magazines.[75] Blacks began to participate more conspicuously, and perhaps more frequently, in some of the lesser temple rituals (e.g., baptisms). One elderly black woman, who had been a Mormon in the Washington, D.C., area for seventy years, was featured in a widely viewed television documentary about the new temple there.[76] Several black Mormons published small books during this period, describing their experiences as converts and members in rather positive terms. Though all private published, these books gained fairly wide circulation among Mormons.[77] Other Mormon blacks freely submitted to interviews with the media, in which they generally defended the Church.[78]

Of special significance was the creation of the Genesis Group late in 1971, an enterprise still very much alive a decade later.[79] This group was organized as a supplement, not a substitute, for the regular church activities of Mormon blacks in their respective Salt Lake area wards. Led by a group presidency, their program consists of monthly Sunday evening meetings, plus Relief Society, MIA, choir and other auxiliary and recreational activities. With a potential membership of perhaps 200, its participation levels have ranged between about twenty-five and fifty, consisting disproportionately of women, of middle-aged and older people, and of high school-educated skilled and semi-skilled workers.[80] About half are partners in racially mixed marriages, and the most active members are (with a few important exceptions) blacks converted to Mormonism in adult life, rather than life-long members from the old black families of Utah.[81]

The Genesis Group was organized mainly on the initiative of the small band of faithful black Mormons who became its leaders. Three of them approached the Quorum of Twelve with a proposal for an independent black branch, to be led by a few blacks ordained to the priesthood on a trial basis—a proposal, in effect, for a racially segregated branch. The main rationale was that the unique predicament and feeling of Mormon blacks called for more intensive fellowship and mutual support than their residential dispersion would normally allow. While the presiding brethren were not yet willing to go as far as an independent branch, they were very willing to sponsor the kind of group that eventually resulted from these negotiations, irregular though the Genesis Group surely was.[82]

A special committee of three apostles was appointed to organize the new group and oversee it, though eventually it was placed directly under stake jurisdiction.[83] It is not clear just what future the apostles envisioned for the Genesis Group, but to its members it represented the beginning of a whole new era for Mormon blacks, and they chose its name accordingly. While leaders of the group were not ordained to the priesthood, they had the distinct impression—whether on adequate grounds or not—that their organization was a step in the direction of eventual priesthood ordination, and they believed, furthermore, that such an expectation was shared by leading members of the Twelve.[84]

The official mission given the Genesis Group at its inception, however, consisted mainly of the reactivation or proselyting of blacks in the area. Early on, the group inevitably acquired other functions: (1) It came to serve as a kind of unofficial speakers’ bureau for wards and stakes in the area seeking more association with Mormon blacks and more acquaintance with their feelings; this, in turn, contributed to the growing visibility of blacks in Utah church circles. Also (2) the group provided a vehicle for mutual support, counseling, and fellowship among Mormon blacks themselves, and a legitimized forum for the expression of aspirations, frustrations, or even bitterness. There was, of course, the inherent risk that the Genesis Group might move into a more militant form of consciousness-raising. It is a comment on the loyalty of the group members that such did not happen despite occasional outbreaks of acrimony.[85]

Since the end of the priesthood ban, the mutual support function of the group has perforce been expanded to include the counseling and fellowship ping of new black converts from around the nation (by telephone and mail) who are having trouble with both the historical and the residual racism they may have encountered on joining the Church.[86] One would expect that such activities will become less burdensome as racism recedes, and more black converts join such thriving branches as the one recently organized in the Watts area of southern California.[87] Meanwhile, the Genesis Group has been rendering the Church and its black members a unique and selfless service.

The Year of No Return: 1974

We are not yet in a position to know what cumulative impact the events of the 1970s may have had behind the closed doors of the highest councils of the Church. We have already noted that the relentless public pressures of the 1960s do not seem to have been sustained into the next decade. Not that there was a lack of vexing incidents: the 1972 confrontation with New York City blacks; the cancellation of the Tabernacle Choir tour and the run-in with the Boy Scouts in 1974; and the highly publicized excommunications and related harassments of 1976 and 1977.[88] These tended to be separate and ad hoc in nature, however, and usually could be brought to closure in a limited time with limited public relations damage, unlike the endless and orchestrated barrage of the 1960s.

The external and public episodes of the 1970s are thus not as likely as the internal developments in the Church to provide the explanation for the decline and fall of the priesthood ban on blacks. When the historical documents are made available, we are likely to see the year 1974 emerge from the data as the crucial year of no return: the year, that is, when the decline of the priesthood ban entered a steeper phase, and its end became not only inevitable but imminent. It is not merely that 1974 was the year that Spencer W. Kimball assumed the presidency.[89] To be sure, President Kimball was to play the most critical role in ending the ban, but it is unlikely that he saw himself in that role as he took office. His 1974 interview on the Today Show makes it clear that while he was praying about the matter, he did not think change was imminent.[90] Still, he was praying about it, and, ultimately, in a manner that Bruce R. McConkie implies may have been unprecedented.[91] Certainly by the time the historic revelation came in mid-1978, President Kimball had been agonizing over the issue for some time.[92]

For just how long we are not sure. However, he could not long have remained unmindful of the consequences of the decision, made during his very first year as President in 1974, to build a temple in Brazil. By that time, there were four missions, nine stakes and 41,000 Latter-day Saints in Brazil alone.[93] It was a matter of grave concern to the mission presidents and regional representatives who had served recently in Brazil, which they surely must have communicated to President Kimball and his colleagues, that racial intermixing for hundreds of years in that country was making the issue of priest hood eligibility an impossible tangle.[94] It seems unbelievable that a decision would deliberately have been made to build a temple in the most racially mixed country on the continent without a concomitant realization (or a rapidly emerging one) that the priesthood ban would have to be ended. It is in this sense that 1974 was a year of no turning back, and that is why Jan Shipps and others are probably correct in seeing the eventual revelation of 1978 as far more the product of internal pressures like Brazil than of external pressures from public relations.[95]

The quicksands of the lineage-sorting enterprise also were brought forcibly to the attention of some members of the Quorum of the Twelve by another development in the mid-1970s. While this development fortunately remained an internal one, it could easily have become public, with a high potential for scandal. For some time there had been a group of trained genealogists, full-time church employees, who assumed responsibility for reviewing complicated lineage problems referred from around the Church. These genealogists reported directly to a member of the Twelve, and made recommendations about priesthood eligibility in hard cases. From an internal ecclesiastical point of view, the arrangement made perfectly good sense: few church leaders at either the local or general level felt that they had the expertise to make crucial judgments about lineage in individual cases.

The existence of this screening process became problematic when the Church became aware of proposed legislation pending in Congress which would have prevented access to the 1900 census records stored under the control of the U.S. Archivist. The Church was interested in this legislation because the 1900 census contained information of critical value to genealogists. (Such data were of great interest also to the University of Utah medical school, a major center for the study of family disease histories.) The problem grew more complicated, however, when the head of the Bureau of the Census opposed release of the data because he believed it an invasion of privacy for the Church to use census information for genealogical purposes which ultimately led to “bizarre” temple ceremonies vicariously involving people who were not even Mormons. As the bill moved through committee hearings, certain black members of Congress also opposed the bill because of the priesthood ban on blacks. In such a context, the outside discovery of a church group specializing in black lineage identification not only would have scuttled the Church’s legislative efforts, but would also have created a major public relations embarrassment.[96]

As things turned out the three or four year tug-of-war in Congress over the access issue ended indecisively, but in 1976 the hazards of the Church’s group of lineage specialists were brought quietly to the attention of certain members of the Twelve.[97] Some friction among the Brethren subsequently developed, for the lineage screening program, it seems, was a surprise even to some of the Twelve, and approval for the enterprise was not universal among them. Exactly what ensued thereafter is not clear, but the sensitive screening program at the headquarters level does seem to have been dropped, for an official letter from the First Presidency eventually quietly transferred to stakes and missions the final determination of “whether or not one does have Negro blood.”[98]

The New Revelation and Its Aftermath

The Stage is Set

In the Spring of 1978, as the new revelation waited in the wings, there was no inkling of its pending dramatic entrance to center stage. The charged deliberations of the presiding brethren during the weeks immediately preceding had obviously been carried on in great secrecy, preventing the preliminary rumors that had been “leaked” during earlier and abortive deliberations in 1963 and 1969. Yet, as we have seen, the new revelation was not as sudden a reversal of the status quo as it may have seemed. The stage had clearly been set. Many trends had merged into a common strain toward greater parsimony, and ever greater limitation on the impact and implications of the traditional priesthood ban. These trends had the effect of preparing both the leaders and the membership of the Church for the new revelation.

First, there was the gradual constriction of the scope of the ban within the Church, a casting of the net less broadly, as it were. Whole categories of people were moved out from under the ban, as in the South Pacific. The burden of proof in the case of dubious lineage was shifted from the questionable family or individual to the priesthood leaders and the Church, not only in North America, but also in South Africa and even in the hopelessly mixed countries of Latin America. A certain looseness at the boundaries of the ban was also apparent in the decentralization and delegation of the decision-making about priesthood eligibility, at first partially and then (by February, 1978) totally. Another way of seeing this trend would be to say that by the time Spencer W. Kimball became president, there were far more categories and situations among mankind eligible for the priesthood than had been the case when David O. McKay had assumed the presidency.

Then there was a corresponding trend toward reducing the implications, or damage, as it were, deriving from the priesthood ban in the external relationships of the Church with the world. First, starting in the early 1960s, the Church increasingly attempted to strip the priesthood policy of any social or civic implications, embracing the civil rights doctrines of the nation and eventually putting the Church behind progressive legislation in Utah. Every official statement from 1963 on emphatically denied that the internal church policy provided any justification for opposition to civil rights for all races. At least equally important was the deliberate and rapid public redefinition during the 1970s of blacks, Mormon or otherwise, as acceptable and desirable associates and equals. A new media image for blacks always had been part of the thrust of the civil rights movement as a whole in America, but for Mormons the most salient medium was ultimately their religion, and particularly its public and official posture. As long as the black man appeared to be regarded by Mormon leaders as persona non grata, or even as “the invisible man,” Mormons would probably keep their distance, despite a formally proper equalitarian stance in civic affairs. The new message seemed to be, then, that the priesthood ban justified neither the denial of civil rights nor the apprehensive social avoidance of black people.

The third important expression of the trend toward parsimony was the gradual discarding of the traditional theological justifications for priesthood denial. This evolution is obvious from a systematic comparison of official Church statements across time: the First Presidency letters of the 1940s (so reminiscent of the nineteenth century lore distilled by Joseph Fielding Smith in 1931); their counterparts in the 1960s, either avoiding theology altogether or espousing only “reasons which we believe are known to God, but which He has not made fully known to man”; and finally the stark declaration by the Public Communications Director of the Church (presumably on behalf of the First Presidency), on the eve of the new revelation, that “[a]ny reason given . . . [for priesthood denial] . . . except that it comes from God, is supposition, not doctrine.”[99]

The Dramatic Moment Arrives

With the doctrinal scaffolding thus removed, the priesthood ban itself reduced in scope to the bare minimum, and a new visibility and identity created for blacks in the Mormon milieu, all that was left of the residue of racism was a restrictive policy of priesthood eligibility under increasing strain. The public announcement of its demise was dramatic but not elaborate—scarcely 500 words long: It began by citing the expansion of the Church in recent years, and then alluded briefly to the expectations that some church leaders had expressed in earlier years that the priesthood would eventually be extended to all races. Most of the brief statement, however, was devoted to legitimating the policy change by reference to direct communication with Deity, which the prophet and his two counselors “declar[ed] with soberness” that they had experienced “.. . after spending many hours in the upper room of the temple supplicating the Lord for divine guidance.” After these strenuous efforts, the Lord’s will was revealed, for he ” . . .by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come when every faithful, worthy man in the Church may receive the holy priesthood . . . without regard for race or color.”[100]

The optimistic (if unsupported) observation of Arrington and Bitton may be true, that the new revelation “was received, almost universally, with elation.”[101] Some credence for that observation may be found in a systematic survey of Salt Lake City and San Francisco Mormons more than a decade ago, which found that more than two-thirds of the sample were ready to accept blacks into the priesthood, or at least did not oppose it.[102] If one can accept the proposition that Mormon public opinion had been well prepared for changes in the status and image of blacks, then widespread acquiescence in the new policy would be expected, the more so in a religion stressing the principle of modern revelation.

At the same time, however, in parts of the Mormon heartland, at least, there was a period of discomfiture that expressed itself in the circulation of some rather bad jokes at the expense of our newly enfranchised black brothers and sisters.[103] And it may well be awhile yet before most white Mormons, at least in North America, will be free of traditional reservations about serving under black bishops, or watching their teenagers dance with black peers at church social events. In all such matters, one can hope that we follow the compelling example of the Saints in New Zealand, where “Mormons are the most successful of all churches in the implementation of a policy of integration . . . This applies to the absolute numbers of Maoris who are in meaningful interaction with Pakehas [whites] in face-to-face religious groups . . . [as well as to] . . . their effectiveness in reaching and moulding their members into cohesive communities …”[104]

The public relations build-up on blacks was greatly intensified in the year immediately following the new revelation and has only partly slackened since then. The first rush of publicity had to do with the rapid ordination and advancement of many faithful Mormon blacks into the ranks of the priest hood, into stake presidencies and high councils, into the mission field and into regular temple work for themselves and for their dead.[105] Besides the coverage of these events in Church publications, Salt Lake City’s Sunday evening television talk show, Take Two, in early June, 1978, featured the entire presidency of the Genesis Group, by then fully ordained, who presented a very upbeat image in expressing their own feelings and in answering numerous “call-in” phone calls.[106] Interest apparently has remained high also in stories about conversions of American blacks to Mormonism: The Church News carried a major feature article on this subject in 1979, and another first person account published in 1980 has sold well in bookstores around Utah.[107] Appearances at BYU by Eldredge Cleaver in February and July of 1981, together with the highly publicized prospects that he might join the Mormon Church, introduced a note of ultimate irony into the continuing Mormon black detente.[108]

At least as much publicity has been lavished on the burgeoning (if belated) proselyting efforts among black populations in Africa and elsewhere. It seemed especially appropriate and symbolic that the first new missions to be opened, just weeks after the new revelation, were in Nigeria and Ghana, where the proselyting efforts of fifteen years earlier had been so tragically aborted. The two mature and experienced missionary couples first sent to West Africa in 1978 literally exhausted themselves baptizing eager new members of the Church. After only a year, they had baptized 1,707 members into five districts and thirty-five branches of the Church in Nigeria and Ghana.[109] Meanwhile, the rapid growth of the Church already underway in Latin America and the Pacific Islands continued with much publicity toward the day of the dedication of the Brazilian temple late in 1978. The Church was clearly making up for lost time in all such areas, and it was anxious for the world to know it.

Apart from these developments, it seems fair to add that the new revelation has provoked neither the wholesale departure of die-hard traditionalists from the Church, as one had heard predicted occasionally, nor the thundering and triumphant return of marginal Mormon liberals, who so long had become accustomed to citing the priesthood ban on blacks as the major “reason” for their disaffection. Those disposed to apostatize over the ending of the ban seem already to have done so over the Manifesto of 1890, for polygamous fundamentalists offered the only apparent organized opposition to the new priesthood policy (as just another “retreat” from orthodoxy).[110] The liberals, for their part, scarcely had time to notice that their favorite target had been removed before they were handed a new one in the form of the ERA controversy. Mormon intellectuals, whether liberal or not, have reacted predictably with a number of publications (like this one) offering post-mortems on the whole Mormon/black controversy.[111] Commentators outside the Church generally have shown only mild interest in the new revelation; in fact it was old news within a few days.[112]

Reflections and Reconciliations

If the Church, then, has reacted to the new revelation mainly with white acquiescence and black conversion, does that mean that all is well in Zion? The answer depends upon how much we care about certain unresolved historical and ecclesiastical issues. Some of these, of course, have been lingering in the minds of concerned Mormons for decades, as many of us have struggled to understand and somehow explain (if only to ourselves) the anomaly of the pharaohs’ curse in the Lord’s church. Even the change in policy evokes reflections and questions for the loyal but troubled mind: (1) Why did we have to have a special revelation to change the traditional policy toward blacks; and, if it was going to come anyway, why didn’t it come a decade earlier? (2) Since the policy was changed by revelation, must we infer that it also was instituted by revelation? (3) How can we distinguish authentic doc trine in the Church from authoritatively promulgated opinion? (4) Now that the era of the pharaohs’ curse is over, how should we deal with it in our retrospective feelings?

The Necessity and Timing of the New Revelation

There is obviously no point in debating whether a revelation from the Lord “really” occurred. The committed Mormon will take the proposition for granted, while the secular and the cynical will reject it out of hand. In practical terms, it makes little difference whether the Lord or the Prophet was the ultimate source of the revelation, for we are obliged as much to seek understanding about the mind of the one as of the other. It is clear from the reflections of President Kimball and other participants in the revelational process that they all shared a profound spiritual experience, one which swept away life-long contrary predispositions.[113] This experience was apparently a necessity if the priesthood ban ever were to be dropped, if for no other reason than that all earlier attempts to resolve the problem at the policy level had bogged down in controversy among the brethren. Only a full-fledged revelation, defined as such by the president himself, would neutralize that controversy and bring the required unanimity among the First Presidency and the Twelve. Moreover, for years nearly all the General Authorities who had spoken publicly on the priesthood ban had been clear in stating that it could be changed only by direct and explicit revelation.

Why didn’t the revelation come earlier, before all the public relations damage was done? This is much too complex a question to be answered by the facile conventional wisdom of church critics: namely, that the obstinately backward Mormons finally got their “revelation” when the progressive forces of the outside world applied sufficient pressure.[114] Such an “explanation” betrays ignorance of the complex dynamics operating within the Church during the 1960s and 1970s, and of certain crucial Mormon ecclesiastical imperatives. Furthermore, it ignores the several years’ respite from external pressure which the Church had generally enjoyed before 1978, and which, indeed, gave the new revelation much of its quality of surprise.

Prophets in the Mormon tradition do not sit around waiting for revelations. Like church leaders at all levels, they grapple pragmatically with the day-to-day demands and problems that go with their callings, presumably striving to stay as close as possible to the promptings of the Holy Spirit on a routine basis. They are not infallible, and they sometimes make mistakes. They carry the initiative in their communication with Deity, and when they need special guidance they are supposed to ask for it. Even this inquiry is often a petition for confirmation of a tentative decision already produced by much individual and collective deliberation.[115] That means that prophets are left to do a lot on their own; it means, too, that receiving a special revelation may depend on previously identifying an appropriate solution.

All of this leads to the point that the timing of the new revelation on priesthood eligibility was dependent in large part on the initiative of President Kimball himself, who had to come to a realization, in his own due time, that the Church had a serious problem; then he had to “study . . . out in his mind” a proposed solution to the problem, and only then petition the Lord for confirmation of the proposal.[116] Bruce R. McConkie, a direct participant in the process of collective affirmation that followed President Kimball’s own solitary spiritual sojourn, described the president’s approach very much in these terms, strongly implying furthermore, that he was the first President of the Church to have taken the black problem that far.[117] If so, we already have much of the explanation for the timing of the end of the pharaohs’ curse.

Given the relatively restrained role of Deity in the revelational process just described, we are then entitled to wonder just what were the considerations that brought President Kimball to frame his proposal and petition the Lord for its confirmation.

I have argued that inside pressures from outside Utah were probably more compelling than outside pressures from inside Utah. Brazil was not the only consideration, of course, but it was surely the most immediate and weighty of the Third World examples. When the 1974 decision was made to build a temple in Brazil, the realization among the brethren must have developed rapidly, if indeed it was not there to start with, that the priesthood ban would be untenable and unmanageable. This point has been noted not only by so astute an outside observer as Jan Shipps, but also explicitly by Apostle LeGrand Richards and implicitly by Bruce R. McConkie and by President Kimball himself.[118]

The exact timing of the revelation ending the “Negro issue” for the Church, however it is best explained, was providential in a public relations sense as well. Damage to the public image of the Church could probably have been averted altogether only by dropping the priesthood ban before it became a public issue. One viable chance for that, and maybe the last one, was lost when the First Presidency failed to reach consensus in 1954. Once the NAACP and other civil rights partisans took up the issue in the early 1960s, the Church could not have changed the Negro policy without, resurrecting from polygamy days the specter of a pressure-induced “revelation on demand”. Even with the pressure off, in the late 1970s, critics of the Church made cynical comments in that vein, but with much less credibility. Had the new revelation come instead a decade earlier, at the height of the political agitation, there would have been little room for anything but a cynical interpretation of how the prophetic office is conducted. It seems certain that to most Mormons, maintaining the integrity and charisma of that office was a more important consideration than either racial equality or societal respectability. There could be no re-enactment, in Mormom vestments, of the assault of aggiornamento upon the papacy.[119] It seems understandable, then, that the timing of the new revelation should have fallen well after the apex of the civil rights movement, but before a temple opened in Brazil.

Terminal vs. Initial Revelation

There is ho known record of any revelation in this dispensation that either denies the priesthood to blacks or ties them to the lineage of the pharaohs. Nor is there any record that the Church had a policy of priesthood denial in the lifetime of Joseph Smith. There is much evidence that the policy developed after Brigham Young took charge of the church.[120] Was that policy established by revelation? We may never know, but it is not necessary to believe so. There is an especially relevant biblical precedent suggesting that ecclesiastical policies requiring revelation for their removal do not necessarily originate by revelation. The controversy over circumcision among the New Testament apostles offers us a parallel problem of “racial discrimination.” If Jesus had given some priority in the teaching of the gospel “to the Jew first, and also to the Greek,” he certainly never instituted the requirement of circumcision before baptism for the Gentiles, as some of his early apostles apparently believed. In spite of Peter’s vision about “unclean meat,” which should have settled the question, it is clear from Paul’s epistles that the circumcision controversy in the early church lasted for many years.[121] We may well wonder why the Lord “permitted” a racially discriminatory policy to survive so long in either the ancient or the modern church, and what circumstances finally brought about his intervention. It does seem plausible, however, that both the ancient and the modern instances could have had strictly human origin. An open admission of this realization may be the best way to start dealing with the black issue in Mormon history. There is no reason for even the most orthodox Mormon to be threatened by the realization that the prophets do not do everything by revelation and never have.[122]

The Issue of Authentic Doctrine

The changing definitions surrounding the black man in Mormon history raise the question, as few other issues have, of just what is authentic doctrine in the Church? That we had an official policy or practice of withholding the priesthood from blacks cannot be denied. The doctrinal rationale supporting that policy, however, is quite a separate matter. Note, in this connection, that the revelation of June, 1978, actually changed only the policy and did not address any doctrine at all, except indirectly by overturning a common belief that priesthood for the blacks could come only in the next life. It is against this background that Presidents McKay and Brown, and like-minded colleagues, seem to have been correct all along (though perhaps beside the point) in considering the priesthood ban a policy and not a doctrine.

Yet the question of authentic doctrine remains. As we have seen, the flow of doctrinal commentary from the days of Brigham Young, reflected in the First Presidency letters of the late 1940s, is clearly followed by an ebb thereafter to the doctrinal nadir of April, 1978, when1 a spokesman for the Church declared, in effect, that there wasn’t any doctrine on the subject at all. In their private beliefs, however, not all of the brethren followed the lead of the First Presidency in this process of doctrinal devolution. Perhaps the most perplexing case in point is Elder McConkie, who, a few weeks after the June, 1978, revelation, counseled us to forget doctrines expounded earlier by himself and others who had spoken “with limited understanding,” but then chose to retain virtually all the old Negro doctrines in the 1979 revision of his au thoritative reference book![123]

In the quest for authentic doctrine, I find it useful to employ a typology or “scale of authenticity,” which I have derived from empirical induction, rather than from anything formal. It is thus an operational construct, not a theological one.[124] At the top of this scale is a category of complete or ultimate authenticity, which I call canon doctrine, following conventional Christian terminology. This would include both doctrines and (for these purposes) policy statements which the prophets represent to the Church as having been received by direct revelation, and which are subsequently accepted as such by the sustaining vote of the membership. The four standard works of the Church (with recent addenda) obviously fall into this highest category of authenticity, but it is difficult to think of anything else that does.

A secondary category, nearly as important, is official doctrine (and, again, policy). Included here are statements from the president or from the First Presidency, whether to priesthood leaders or to the world as a whole; also, church lesson manuals, magazines, or other publications appearing under the explicit auspices of the First Presidency. General Conference addresses in their oral form should not routinely be included here, or, if so, only tentatively, given the revisions that they have frequently undergone before being allowed to appear in print. There is no assumption of infallibility here, but only that the legitimate spokesmen for the Church are expressing its official position at a given point in time.[125]

The third category of authenticity I would call authoritative doctrine. Here would fall all of the other talks, teachings and publications of authorities on Mormon doctrines and scriptures, whether or not these are published by a church press like Deseret Book. The presumption of authoritativeness may derive either from the speaker’s high ecclesiastical office (e.g., Bruce R. McConkie), or from his formal scholarly credentials and research (e.g., Hugh Nibley), or from both (e.g., James E. Talmage).

The lowest (least authentic) category is popular doctrine, sometimes called “folklore.” This is to some extent a residual category, but it clearly includes the apocryphal prophecies that often circulate around the Church; common beliefs such as that temple garments offer protection from physical injury; and a host of other notions having either local or general circulation. Occasionally a popular doctrine will be considered subversive enough by the General Authorities to warrant official condemnation, but usually folklore flourishes unimpeded by official notice.

Now obviously a particular doctrine can be found in all four categories simultaneously. In fact, such would ideally be the case for canon doctrine, so the “authenticity scale” I have recommended may have a cumulative property in many cases. Indeed, it is rare for a doctrine in a given category not to have some “following” in the lower categories. What becomes crucial for us to determine, however, is how high up the scale is the primary source of a given doctrine or policy. This is a determination rarely made, or even considered, by most church members, who therefore remain very susceptible to folklore, as well as to doctrines that may be authoritative or even official, for a time, but later prove erroneous.

Let us take the traditional “Negro doctrines” as a case in point: These seem to have begun at the level of folklore in the earliest days of the Church, imported to a large extent from the traditional racist lore in Christianity more generally.[126] It is not clear from surviving records how often these doctrines received authoritative endorsement by church leaders during the lifetime of Joseph Smith, but there is little reason to believe they ever became official. By 1850, though, they seem to have been elevated to the official level, if only because President Brigham Young taught them in his official capacity. Most of them were still officially embraced by First Presidency letters in the late 1940s and widely promulgated at the authoritative and folk levels as well. There they now survive, despite withdrawal of official endorsement. Let us note, for the historical record, that neither the priesthood ban itself nor its supporting doctrinal justifications were ever canon doctrines. No known revelation was ever promulgated to establish the ban, or even to tie it to the curse of the pharaohs in the Book of Abraham.[127]

The historical “career” of the priesthood ban and its accompanying doc trines suggests to us the importance of the principle of parsimony in our approach to doctrine. While accepting whole-heartedly the standard works of the Church, we must be very reluctant to “canonize in our own hearts” any doctrines not explicitly included there. We may hold other doctrines as postulates, as long as we realize that they may in the long run prove erroneous, and that we have no right to consider their acceptance among the criteria of faithfulness. The premises of our church membership also oblige us to act in conformity to official policies and teachings of our church leaders; but here we are entitled to entertain reservations and express them to our leaders, since official statements can turn out to be wrong.[128] It is not blind faith that is required of us, but only that we seek our own spiritual confirmation before questioning official instruction.[129]