Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 2

Mormonism and the Periodical Press: A Change is Underway

Mormonism has long occupied a unique place in the consciousness of Ameri cans. In the nineteenth century the Mormon Church was all but cast out of America: its prophet-founder ridiculed as a fraud and a charlatan, and his polygamy teachings assailed in Congress as one of the “twin relics of barbarism.” Only after the manifesto disclaiming polygamy in 1890, did Americans begin to look upon their strange western neighbors in a more favorable light. Despite the stinging criticisms accompanying the subsequent election of B. H. Roberts to the House and Reed Smoot to the Senate, articles began to speak well of the Mormons for the first time.

During the past fifty years, the publicized Mormon values of integrity, devotion to the puritan work ethic and the nuclear family, genealogy, temple work and proper health habits have propelled the Church to a position of considerable respectability and prestige. Two articles in Dialogue characterized the sixties and seventies as a period in which the Church’s message was being accepted with surprising enthusiasm by most of the media.

Now, five years since the last media update, an entirely different image is emerging. Recently the Church has been confronted with some of the most delicate issues in its history, and these have been reported in one sensational front page story after another. First it was the Solomon Spalding controversy, then the Priesthood Revelation, then an escalating ERA cacophony capped by perhaps the most conspicuous media event in church history—the 1979 trial and excommunication of Sonia Johnson. Since then the pace has slackened very little, for the discovery of the Joseph Smith III blessing just over a year later also achieved front page status. This in turn has been followed by a media controversy surrounding the First Presidency statement on the MX missile system. While feature or human interest stories continue to be published on such topics as the Nauvoo Restoration, missionary work, Mormon athletes, or the Saints in the Pacific and elsewhere, these are proportionately less common than a few years ago. The new spotlight reflects more than a serendipitous series of events: the political leverage of the Mormon hierarchy now is viewed by the national powerbrokers as a potent force—and one which no longer can be assuaged by pro forma photographic sessions at 47 East South Temple or the White House. This development is no less reflected in the recent Boston Globe centerpiece headline, “It’s Do or Die for the ERA—Mormon Power is the Key”, than in the unprecented emergence of the Church as a prime subject for the editorial page, both in text and cartoon. Although the Church is being treated with far greater and more subtle pe ception than before, its potent incursions into politics clearly has troubled many leading journalists and left them concerned about the future.

Spalding Controversy

One of the less conspicious of the recent stories, but nevertheless an intriguing one, was a historical challenge which emerged during the summer of 1977. “Based on the evidence of three handwriting experts,” Russell Chandler, a Los Angeles Times religion writer announced on June 25, re searchers had “declared that portions of the Book of Mormon were written” by Solomon Spalding, a Congregationalist minister and novelist who had died in 1816.

The three Southern California researchers—Howard A. Davis, Donald Scales and Wayne L. Cowdrey—Chandler explained, some two years earlier had obtained enlarged photocopies of twelve original manuscript pages of the Book of Mormon from the church archives in Salt Lake City. Three prom inent handwriting experts were asked to compare these documents with specimens of Spalding’s handwriting in “Manuscript Story,” a novel about the origin of the American Indians generally acknowledged to have been written in longhand around 1812. All three of the handwriting analysts— Henry Silver, William Kaye and Howard Doulder—working independently, and unaware of the Book of Mormon connection, agreed that the same writer had probably executed both works.

Soon thereafter Christianity Today and Time carried expanded versions of the story. Time stressed that the researchers were “relying on the sometimes shaky science of handwriting analysis.” Edward E. Plowman, however, chose to emphasize in his July 8 Christianity Today story that the Church was “slowly discovering that a crisis of truth exists in its roots.”

Within days after the first stories appeared, the Salt Lake Tribune learned that Silver had denounced the Los Angeles Times for misrepresenting him, stating that he would be unable to give a definite opinion until he examined the original documents. A week later, Silver withdrew from the study, first citing poor health and then subsequently accusing Walter Martin, whose Christian Research Institute was financing the study, of launching a “vendetta against the Church.” The remaining two handwriting experts visited the church archives in Salt Lake City in July.

In August, John Dart, Los Angeles Times religion editor, summarized the Church’s first detailed response “to claims that part of the original Book of Mormon manuscript was in the handwriting of a novelist, not a scribe for church founder Joseph Smith.” Dart expressed considerable uncertainty as to whether the report prepared by Dean C. Jessee, senior research historian for the Church’s historical department, provided any real clarification.

Early that September, Dart learned that handwriting expert William Kaye’s study showed “unquestionably” that the documents had “all been executed by the same person.” Reaching a totally different conclusion, Howard Doulder concluded in his four-page report submitted two weeks later that the two manuscripts were written by “different authors.” Doulder attributed simi larities “to the writing style of that century.” Howard Davis, as spokesman for the three researchers, told Russell Chandler of the Times that he “kind of expected [Doulder] would go negative on the thing because there had been so many death threats.” When asked if his life had been threatened during his investigation of the Mormon manuscripts, Doubler replied: “Not at all.”

Meanwhile, Mormon archivists were busy assembling a large amount of evidence—some of it impressive—to rebut the Spalding theory. “They scored a coup of sorts,” Edward E. Plowman noted in Christianity Today’s October 21 issue, “when they discovered that a manuscript page from another Mormon book, Doctrine and Covenants, was apparently in the same hand writing as that of the “unidentified scribe in the Book of Mormon manuscript.” That document bore the date June, 1831—fifteen years after Solomon Spalding’s death. Spalding’s authorship was also discredited by Jerald and Sandra Tanner, two ex-Mormons and among the faith’s most vocal critics, in a book prompted by the controversy entitled Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?

Given these developments, Edward Plowman’s reappraisal of the controversy served as a notice that all was not going well for Cowdrey, Davis and Scales whose Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? was soon due off the press. In his concluding explanation of why the handwriting experts had failed to agree, Plowman, in sharp contrast to his earlier expressions, reluctantly admitted that “everyone seems to agree that handwriting analysis is not an exact science.” Less than a week later, Christian Century announced that a computer study by two statisticians at Brigham Young University “shows ‘overwhelmingly’ that the Book of Mormon is the work of many authors.”

Blacks Recieve the Priesthood

Astory of far greater magnitude broke on Friday, June 9, 1978, when the First Presidency of the Church announced a revelation confirming “that the long-promised day [had] come when every faithfu1 worthy man in the Church [could] receive the priesthood.” Time and Newsweek stopped their presses to get the story into their weekend editions. It was carried as well by all of the major radio and TV networks and on page one of leading newspapers across the country.

Although “Mormons get revelations often,” Mario S. De Pillis emphasized in the New York Times, none have been of the magnitude of President Spencer W. Kimball’s announced “revelation from God stating that henceforth black men may hold the priesthood.” This involved the “reclassification of a whole segment of society.”

News of the First Presidency’s announcement, as dramatically retold by Janet Brigham in Sunstone, “was electric—it swept through and stunned the worldwide Mormon community faster than the startled news media could broadcast it.” Even President Jimmy Carter was moved to send a telegram to President Kimball commending him for his “compassionate prayerfulness and courage in receiving a new doctrine.” Howard Sheehy, a member of the RLDS First Presidency, applauded President Kimball’s “courage to make this change in tradition,” but was also quick to point out that the Reorganized Church had permitted blacks to be ordained to its priesthood after an “inspired direction” from Joseph Smith III in 1865. He considered the decision long overdue.

For De Pillis, this was the “only way out, and many students of Mormon ism were puzzled only by the lateness of the hour.” While the Church had weathered its most serious crisis since the abandonment of polygamy and now would doubtlessly enjoy even greater growth in missionary work, the revelation left unresolved, in DePillis’ mind, “other racist implications of the Book of Mormon and the Pearl of Great Price—scriptures that are both cornerstones and contradictions.”

T. S. Carpenter in New Times saw President Kimball’s revelation as “the envy of any politician who has ever longed for a deus ex machina to take him off the hook.” It might well, he contended, “trigger an evangelical offensive in Africa, where Mormon missionaries currently serve only whites in South Africa and Rhodesia. As for black recipients of this spiritual windfall, the rewards will probably be more psychological than tangible. Black businessmen might conceivably benefit by closer religious ties with the entrepreneurs in the Mormons’ billion dollar financial empire.”

The greatest beneficiaries of the revelation, Kenneth L. Woodward of Newsweek reasoned, could well be the “white Mormon majority” who would no longer have to be considered bigots. “By reversing its long-standing exclusion of Blacks from its priesthood and temple rites,” Edwin S. Gaustad, a professor of history at the University of California at Riverside, wrote in the Los Angeles Times, that the Church had “eliminated a major source of embarrassment and external pressure.” While he readily recognized that many still criticized the Church for not permitting women to hold the priesthood, Gaus tad was quick to point out that the Mormons were not alone on that point. “Indeed if women are ever to claim full participation in the world’s major religions, revelation must broaden its beam to reach well beyond Salt Lake City—to Canterbury and Rome, to Constantinople and Jerusalem, and to the uttermost parts of the earth.”

Molly Ivins in the New York Times, William F. Willoughby of the Washing ton Star and Russell Chamberlain of the Los Angeles Times considered the Mormon Church’s decision to change its 148-year-old policy as the most significant action since its ban on polygamy. Others thought the revelation might smooth the way for better relations between the Church and the nation’s blacks and provided another example of the adaptation of Mormon beliefs to American culture.” David Briscoe and George Buck depicted it in Utah Holiday as “a new era of potential brotherhood [which had] opened up in a moment—with its attendant opportunities and challenges.”

“Despite the seductive persuasiveness of this interpretation,” Jan Shipps felt the revelation would “never be fully understood if it is regarded simply as a pragmatic doctrinal shift ultimately designed to bring Latter-day Saints into congruence with mainstream America. The timing and context, and even the wording of the revelation itself, indicate that the change has to do not with America so much as with the world.”

Revelations in Mormondom are generally the products of a lengthy proc ess, Shipps told Christian Century readers. “During the 1960s the Church was under tremendous pressure from its critics on this issue. Early in the 1970s “liberal Latter-day Saints agitated the issue from within.” What prompted “President Kimball and his counselors to spend many hours in the Upper Room of the Temple pleading long and earnestly for divine guidance did not stem from a messy situation with blacks picketing the Church’s annual con ference in Salt Lake City, but was ‘the expansion of the work of the Lord over the earth.'”

ERA and Sonia Johnson

By the fall of 1979, another of the Church’s alleged prejudices captured the media’s imagination as Marion Callister, a Federal judge in the U.S. District Court in Boise, and also a regional representative of the Church, refused to disqualify himself in the case of Idaho et al, v. Freeman, wherein Idaho and Arizona, plus four Washington state congressmen, challenged the constitutionality of Congress’ extension of the deadline for ERA ratification. They sought validation of a state’s right to rescind an earlier ratification.

The Mormon-ERA connection, of course was not a subject new to the media. Articles had appeared on the general theme for much of the 1970s. Lisa Cronin Wohl, for example, focused on the Church’s anti-ERA lobbying efforts in Nevada in the July 1977 Ms, to dramatize how “church participation on the ERA went way beyond the bounds of merely encouraging its members to vote.”

When “Mormons for ERA” was formed in 1978, it introduced a prominent subtheme into the coverage. Lynn Simross, Los Angeles Times staff writer, in a lengthy May 1979 piece, described feminist Mormon supporters of ERA as having “disrupted the Mormon patriarchy. And because of this, they say, among women there is schizophrenia in Zion.” Using virtually the same language, Virginia Culver, the Denver Post’s religion editor, saw “feminists in the Mormon Church walking a tightrope. They feel loyalty to their church and believe its tenets. But they want some changes, some loosening up.” Although some think they can handle this balancing act, “others are uncertain about whether to stay and try to change the church dictums or to leave.”

The Callister controversy stimulated considerable editorial comment as well. “Perhaps Judge Callister can weigh the merits pro and con on the ERA ratification extension to the satisfaction of all parties,” the Kansas City Times declared, “but it seems highly unlikely. Regardless of his approach, it will be difficult for him to convey the appearance of justice in a decision for or against ERA.” That, according to the Times, was because his church is so “deeply involved in opposing the issue before him and he is so deeply involved in his church.”

While the Philadelphia Inquirer considered it inappropriate “to set a pre cedent whereby an individual judge’s private religious beliefs could be used to disqualify him from a case would be a grievous mistake . . . the Mormon Church’s active opposition to the ERA coupled with Judge Callister’s position of leadership in the Church” made this a special case. The Detroit News likewise conceded that “it would be a grievous error to assume that a judge’s religious beliefs render him incapable of impartiality,” but was adamant in insisting that Callister should step aside.

Callister’s “presence in the courtroom,” the Boston Globe argued, “would certainly color, and possibly distort the proceedings. And supposing Callister was found in favor of ERA? Would he then find himself in the same untenable position as [recently excommunicated Mormon ERA exponent] Sonia Johnson? Would he face a reprimand or punishment from his church?”

The New York Times thought it was “entirely reasonable” for supporters of the ERA to be worried that Judge Callister’s “high church rank and duties might influence his judgment on a matter of such importance to the Mormon high command.” Courts everywhere would eventually have to face the serious issue which this case raised.

If Judge Callister were merely a member of the Mormon Church,” columnist Ellen Goodman suggested, “it would be inappropriate to criticize his capacity for objectivity.” The problem stems from Callister’s position as a “church decisionmaker, several rungs higher than the bishop who excommunicated Sonia Johnson. He was part of the inner circle that has already passed judgment on the extension and recision issues.”

Taking exception, Ronald Goetz in the January 1980 Christian Century characterized the movement to remove Callister as an “effort to amend the U.S. Constitution toward greater human liberation and justice” while at the same time trampling on “some of our already-won, longstanding constitutional rights.” “Surely,” Goetz reasoned, “the guarantee of religious liberty is threatened in this attempt to exclude Judge Callister.”

Despite its avowed support for ERA, the Los Angeles Times also declared that “it would be a serious mistake for the Justice Department to ask formally for Callister’s disqualification. . . . American jurisprudence is based on the assumption that a judge can indeed separate state and church in his official duties.”

If Callister “is forced to disqualify himself,” Patrick Buchanan proclaimed late in 1979, “a nasty precedent will be established.” Catholic judges as well as other jurists would as a consequence also be asked to disqualify themselves from cases ranging from abortion to annual appeals asking for removal of Christmas celebrations from the public schools. “And what of the adherents of our secular faith?”

Among his fellow Idahoans who knew Callister best, the New York Time’s Molly Ivins reported “little alarm or indignation.” Even Senator Frank Church, an Idaho Democrat, and Republican Steve Symms, who would subsequently unseat him in 1980, and who “managed to disagree about almost everything,” were “united in their support for Judge Callister.”

Even Callister’s release as a regional representative, however, did little to temper the opposition. As the controversy surrounding Judge Callister intensified, another Mormon emerged as a major focal point of media attention. Mormonism—so far as the media was concerned—never had had a woman quite like Sonia Johnson, or at least not one as newsworthy. Sonia Johnson’s “dilemma,” as the Boston Globe characterized it, dramatized “one that many men and women have lived in recent years as they have been pushed to weigh their own beliefs against the sometimes contradictory tenets of their religions.” The questions confronting Sonia, the Globe’s Ellen Goodman con tended, were “important to every woman and man who believes in equal rights and belong to a church opposed to them,” important to anyone who had ever “felt uplifted by religious beliefs and put down by religious institutions.”

By far the most prevalent charge against the Church was that of mixing religion and politics. Barbara Howard in her February 1980 Christian Century profile on “Sonia and Mormon Political Power,” seriously questioned the right of any church “to engage in political activities under banners other than their own.” Using such tactics, wealthy institutions such as the Mormon Church could influence “decisions affecting numbers of people who are unaware that the opposition is not political, but religious.”

As a consequence, Sonia Johnson’s excommunication “may need to be looked at more closely—not simply because of the ERA but also because the Constitution does call for responsible relationships between religious institutions and governmental powers.” This case also, according to Cari Beau champ, of the National Women’s Political Census, emphasized the legal problems the Church might face by using their tax-exempt funds for lobbying and political purposes.

For Richard Cohen of the Washington Post, the “dispute with Johnson [was] not over something like liturgy, but over the ERA, which is after all, about the rights of women. When the Mormon Church went after Johnson, it attempted to silence a voice—not just a Mormon voice, but a voice. If the Church succeeds, not just Mormon women will suffer, but women in general.” By making a political issue into a religious one, Solveig Torvig told Newsday readers late in 1979, the Mormon Church had removed its “mantle of holiness” and made its “theology and motives fair game for political dissection in the temporal arena.” It was a pure and simple case of “intolerable male arrogance.”

A few weeks later, Linda Sillitoe and Paul Swenson used Utah Holiday to show how Sonia’s excommunication had “dramatized for the nation the outward LDS Church political activities surrounding the Equal Rights Amendment, and the struggle of individual conscience vs. group loyalty within the Church.” Sillitoe in a subsequent article, published by Sunstone, portrayed the “current polarization among Church members as understand able.” Many, she explained, saw Sonia’s troubles resulted not from ERA, but from a lack of “obedience and loyalty to the Church.” Others considered her “separation of the political and spiritual aspects as valid and for her—and possibly for themselves—necessary.”

Using equally forceful language, Chris Rigby Arrington depicted Sonia’s battle as a “political one, but the air around it [was] fused with religion, and there is a complex, spiritual foundation to her convictions.” Arrington stressed in the October 1980 Savvy her belief that “for years to come when Americans think of Mormonism, they will think of Sonia Johnson before they think of polygamy or the Tabernacle Choir.”

The Chicago Tribune’s Charles Madigan characterized the charges against Sonia as a “throwback to the era of the Spanish Inquisition: knowingly preaching false doctrine, undermining the Church’s missionary efforts and its authority.” London’s Economist considered the whole process to be “latterday bigotry” and emphasized that the “place of women in the Mormon Church is not high.”

A few writers, such as Jan Shipps, attempted to provide a broader basis for understanding Mormon Excommunication. Shipss’ January 1980 Christian Century article focused first on the importance of the nuclear family as the basic unit in Mormon culture, and then explained that “any threat to the traditional structure of the family is . . . likely to be perceived as a threat to Mormonism itself.” Because Sonia’s excommunication had received so much attention, people everywhere had heard the “message that Latter-day Saints really care about what happens to the family.” Whether, as a result, “there will be a more than ordinarily abundant Mormon harvest of American con verts remains to be seen.”

Similar observations were espoused by David Macfarlane in the January 1980 Maclean’s. ERA, as far as the Church was concerned, was not “primarily a political or legal issue but a moral one, as fundamental as they come, and well within its jurisdiction.” Johnson and her ERA supporters, however, saw things differently. “They believe that ERA will only strengthen the family by strengthening the position of the mother. Furthermore the issue of ERA, in their view, is a political one, not subject to interpretation by scripture.”

Both opponents and supporters agree, Macfarlane concluded, that “ERA will have a significant impact on U.S. constitutional litigation and judicial decisions. It will have far-reaching effects on the structure of American society, and the Mormons fear—not unreasonably—that the family will bear the brunt of the social upheaval.”

Looking at the excommunication as a necessary and positive decision, syndicated columnist Patrick Buchanan called Bishop Jeffrey Willis “the real hero,” and Sonia “our newest media martyr.” Traditionally, Buchanan explained, religious martyrs “are men and women who surrender their lives rather than deny or contravene the teachings of their faith. In modern times, a media martyr is an individual involved in a popular and trendy cause whose fate customarily includes a sympathetic shot on ‘Good Morning America’ or the ‘Today Show.'”

No one demanded that Sonia “stop talking about ERA,” Buchanan argued. “She was only asked to cease assaulting the church structure, defying church doctrine and distorting church teaching. If she could not agree to that, she should have been excommunicated.” Instead, she “quite obviously preferred to become a publicized heroine of the feminist movement than to remain a member in good standing of the Mormon Church.”

In a December 1979 Washington Post op-ed piece, Sonia herself expressed the belief that the Church was in the midst of a “serious moral crisis. Its decisive crossing over into the anti-ERA politics has eroded in most members’ minds the crucial distinctions between church and state that our Constitution guarantees.” She was particularly concerned that the Church’s “covert and less than strictly ethical political activities [might] be a compromise with integrity that it simply could not afford.”

Sonia’s article was counterbalanced by another piece a few days later, this one by Eleanor Ricks Colton, president of the Washington, D.C. Stake Relief Society. Colton in reiterating the Church’s position for the Washington Post, stressed that Sonia had been “excommunicated for apostasy, not for her position on ERA. Sonia chose to attack the Church and its leaders and urged non-members to reject its missionaries.” As a consequence “she could not expect to remain a member in good standing.”

“Although the official Mormon stance is that its opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment is a moral one, not one that involves political issues,” Diane Divoky of the Sacramento Bee wrote in May 1980, “Mormons have been central in the anti-ERA movement that has brought ratification of the amendment to a halt.” Sonia Johnson’s sin was not her pro-ERA rhetoric, Divoky argued, but her descriptions of the role of her church in calling Mormon women “out of their homes to lobby against ERA with funds which were raised with the blessings of church authorities in Salt Lake City.”

A sizeable portion of those funds, Linda Cicero and Marcia Fram of the Miami Herald found in April 1980, were part of “a massive last-minute campaign that funneled thousands of dollars into the Florida election . . . for candidates who would vote against the Equal Rights Amendment.” Cicero and Fram quoted unnamed sources within the Church as saying that their leaders had “set a goal of $10,000 for each candidate and estimated that $60,000, if not more, was contributed within a 17-day period before the November 7, 1978 election.”

The most critical “questions posed by what took place in Florida,” in Cicero’s mind, centered on “whether the Mormons who contributed money were exercising a political right or responding to religious appeal and whether they perceived the requests as coming from individuals—or as coming from the spiritual leaders of the Church. In a follow-up piece, the Sacramento Bee’s Divoky explained how a sizeable portion of those funds had been raised through contributions from Sacramento and Bay Area Mormons.

Even now, after Sonia has passed somewhat from the spotlight, the Mormon-ERA connection continues. “Today, as its opponents crow and its pro ponents despair, the Equal Rights Amendment is nearly dead,” but Judy Foreman of the Boston Globe contended in late June 1981, there was “one man—one epiphany—that could deliver” the final three States needed for the ERA to become part of the Constitution. “The man is white. He is 86 years old.” That “man is Spencer W. Kimball, president of the 150-year-old Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, better known as the Mormons.”

Just how powerful is the Church? “If all groups that oppose the ERA marched off into the ocean and drowned,” Sonia told Foreman, “the Mormons would still kill it by themselves. They are not just a little group of termites: they are head and shoulders above any other group. They are the most powerful and the most wealthy.” Their strength is undeniable, according to Foreman. “Already this has meant a mostly secret, tightly organized, well financed, church oriented drive in key States to kill the ERA.” The Mormons, she felt, will be the “key” obstacles the pro-ERA forces will have to contend with in their last frantic efforts.

The Joseph Smith III Blessing

It was against this background that the Los Angeles Times, New York Times and Washington Star and several other major newspapers on March 18, carried front page stories of yet another, “hot potato” for the Church. A collector of Mormon memorabilia, Mark Hoffman, of Sandy, Utah, had discovered a 137-year-old document which threatened to renew the succession controversy between the LDS and RLDS. Michael Moritz of the Times-Life News Service saw it as offering “evidence that Joseph Smith once considered his son Joseph Smith III, rather than Brigham Young, to be his true successor.” Moritz suggested that “church historians liken the debate to ones that might have occurred had the Israelites questioned the succession to Moses or Christians doubted the leadership of the Church after the Crucifixion.”

During his lifetime Joseph Smith had considered several modes of succession, including lineal designation. Ultimately, a majority of the members became convinced that the leadership of the Church should pass to the Quo rum of Twelve Apostles. This group under the leadership of Brigham Young headed westward toward Utah three years later. A sizeable number of the dissenters still believed that Joseph had wanted his son, Joseph Smith III, to be his heir. This group remained behind and eventually settled in Independence, finally persuading Joseph Smith III to become their leader in 1860.

The newly discovered document containing the transcript of a blessing given by Joseph Smith to his eldest son, eleven-year-old Joseph Smith III, declared in part that Young Joseph “shall be my successor to the Presidency of the High Priesthood: a Seer, and a Revelator, and a Prophet, unto the Church; which appointment belongeth to him by blessing, and also by right.”

Kenneth L. Woodward of Newsweek did not feel the “dramatic discovery” would bring the “two churches together—it is more than a century late to accomplish that—but the paper lends strong historical support to the Reorganized Saints, who choose as prophets lineal descendents of Joseph Smith, Jr.” As Woodward was quick to point out, however, the RLDS “have another problem: their current prophet, Wallace B. Smith, has no brothers or sons.”

Both Time and the Washington Star quoted BYU historian D. Michael Quinn as saying that the terms of the blessing “mean only one thing in the Mormon Church, that Joseph Smith III would be the President of the Church.” Quinn also told Newsweek that it verified “a much-disputed issue in history.” Fred Esplin in his April, 1981, Utah Holiday article also cited Quinn as “one of the best informed” among those historians who claim to understand the blessing.

Quinn in this instance expressed the feeling that the document “supports what historical research has indicated for several years—that Joseph Smith did indeed tell his son in a blessing that he would succeed him as president of the Church. In Quinn’s opinion, it was the “ultimate refutation of those who denied that it had occurred,” but what “we have is a wonderful, beauti ful blessing of a prophet-father to his son, which the son ultimately rejected. There is a great tragedy in that.”

Within a month, the discovery was old news. “Although the document was an important historical find,” Christianity Today stressed on April 24, “neither branch of the church is making a big deal out of it. The RLDS has ‘no interest in pursuing old nineteenth-century battles,’ said Richard Howard, historian of the Reorganized Church in Independence. ‘The Mormon Church has settled the issue of descent to their satisfaction, and we have settled it to ours.'”

Besides, the “two branches” were, according to Christianity Today, already “far apart theologically. The Missouri church is far closer to orthodox Christianity in its views of Scripture and the Trinity than the decidedly unchristian brethren in Utah.”

John M. Crewdson, in a special report to the New York Times provided a useful insight into the “unaccustomed standing” conferred upon the Reorganized Church as a result of the manuscript’s discovery. The document “generated what one church member described as ‘controlled elation’ in Independence. “If the document is authentic—and so far neither side has suggested that it is not,” Crewdson reasoned, “it now seems that six months before he was shot to death by a mob in Carthage, 111., Mr. Smith conferred the legacy of leadership upon his son, known as Young Joseph, as his ‘by right.'” It contradicts the long held position of the Utah branch that the Church’s President should be chosen from the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, while affirming the stance of the Missouri branch.

Crewdson continued by explaining that a statement released by the Utah branch describing the “manuscript as referring only to ‘the possibility’ of Young Joseph’s succeeding his father.” Although it was conceded that “he had been blessed and ‘designated’ by his father, he had not been ordained as his successor and that it was not ‘necessarily a birthright to be president of the church,’ an office that ‘comes by virtue of fitness and qualification.'”

On March 19,1981, an exchange agreement was signed by LDS and RLDS officials, and the document was turned over to the RLDS in exchange for one of the few existing copies of an 1833 Mormon scripture, the Book of Commandments, conservatively valued at $10,000. The exchange was to be conditional for ninety days, pending further authentication by the RLDS. Spokes men of both churches agreed that the discovery of the blessing had done little to improve chances of reconciliation.

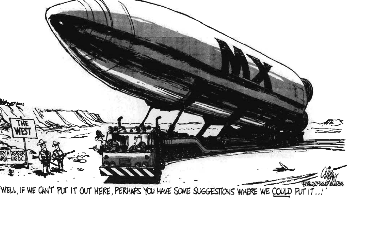

First Presidency Statement on MX

Few issues have proven more provocative in the eyes of the media than the First Presidency May 5, 1981, statement opposing the basing of the MX missile system in Utah and Nevada. Almost immediately after this front page story was carried by the New York Times, Washington Post, and virtually every other prominent paper, syndicated columinist Carl T. Rowan charged the Church with “practicing a morality of convenience.” The Mormons’ “geo graphic morality” should not, he felt, affect decisions regarding MX, even if it bruises Joseph Smith’s dream of a Mormon Shangri-La. He would have felt much better if President “Kimball had said that the Lord had told him” to tell Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger “that he and his Soviet counterpart were commanded to go back to the table and find ways to halt an arms race that endangers everyone.”

Implicit in the logic of the Mormon position, columnist William F. Buckley, Jr., suggested, was the belief “that any installation that harbors instruments of potential destruction somehow mystically contaminates that site. Well the earth is morally neutral, and doesn’t know whether what is being built on it is a missile launching site or a hospital.” The Church’s “solipsistic concern,” was a “thoughtless intrusion into the logic of defense” which “weakens the defense of Western Europe.”

“The Mormon Church’s opposition to the MX missile/’ the New York Times suggested, was “an oddly selective summons to national morality in the service of an obviously parochial interest.” Although it represented a “significant political blow against a questionable weapons project,” it was “also disturbingly sanctimonious. The Church has found its way to a sound conclusion for mostly wrong reasons.”

Using even stronger language, the Nation found the edict laudable but troublesome because “it seemed to imply that the MX, or any other system, was all right somewhere else.” Where then should we put it? “On this, the most urgent question of our time, the Mormon elders offered equivocal guidance.” An equally critical editorial appeared in the St. Louis Post Dispatch.

Conversely, Colman McCarthy of the Washington Post saw the Mormon’s position as “unexpectedly progressive.” In the actual wording of the statement, he reasoned, “which seems not to have been read by some of the Eastern critics in their rush to uncover hypocrisy, the Mormons say they are against basing the MX on land anywhere.” This position was “less a sudden conversion than a return to its heritage. In 1860, when it was a civil war, not a global war that loomed,” Brigham Young himself on at least two occasions denounced the manufacturing of the weapons of war.

Although the St. Louis Post-Dispatch considered it “unfortunate” that the Church had “not taken a firm position against deployment of the [MX] system anywhere,” it also conceded that the statement was in harmony with several earlier pronouncements against nuclear weapons. Government studies, the Baltimore Sun concluded, confirmed that the Church’s concerns were well founded. They welcomed “the Mormon Church’s call ‘to marshal the genius of the nation’ in a search for alternatives less disruptive than the Carter shell game.”

The Post-Dispatch, the San Francisco Examiner, and the Washington Post all saw the Church’s opposition as a formidable political obstacle and a major setback for the Air Force’s new strategic missile. Columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak thought the Church’s statement might well be the “death knell” of Carter’s deployment proposal.” Mormon opposition, the Philadelphia Bulletin reasoned, “should prompt rethinking of the MX plan. Alternatives, such as more missile-equipped submarines, should be newly explored as an interim solution. Interim, that is, to an eventual end to the arms race. The Mormons—and a lot of other people—are for that.”

In Salt Lake City, the Tribune credited the Church with emphasizing “many adverse physical, sociological and human survival factors in the Utah Nevada basing choice.” Even more important was the “fervent plea for forward movement on stalled strategic arms limitation negotiations with the Soviet Union. . . . The implication is clear enough: humanity’s best, perhaps only chance to escape the terror of nuclear war lies in stopping the arms race and intensifying efforts to reduce existing weapons stockpiles.”

Other prominent publications, such as Time magazine, merely chose to report the story or relied on political cartoons, as did the Denver Post, Los Angeles Times and San Diego Union. The Mormon position on MX has probably been as important a source of editorial comment as any issue surrounding the Church in recent memory.

Six weeks after the First Presidency issued its statement, West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, echoing sentiments akin to those of William Buckley, compared the Mormon challenge in the United States against plans to deploy the MX missile in Utah and Nevada with the Protestant opposition to NATO missiles in his country. Schmidt, the Washington Post reported, had gone so far as to warn the Reagan administration that a decision to put the MX missiles someplace else would damage West Germany’s ability to keep its NATO missile commitment.

Broad Overviews

Despite the overriding prominence of the foregoing stories, there have been in recent years several other extensive examinations of Mormonism. Many of these were prompted by the Church’s sesquicentennial. An increasingly subtle and sophisticated analysis is apparent in these articles. Mor mons today, “unlike their forefathers of three generations ago,” Rodman W. Paul believes, have precisely those attributes “one would expect of an affluent, confident middle class blessed with homes of visible comfort.”

Social and economic experimentation among the Mormons, Paul’s June 1977 American Heritage article stresses, are characteristics of another era. This transformation has seen Mormons join the general American trend as they have moved from rural America to dwell in suburbs and cities, and “away from farming and the simple crafts to the professions—commerce, finance, and industry.” They now direct major business and real estate operations in most of the nation’s major cities and are prominent and influential as politicians at every level of government.

Still, there remains a remarkable cohesiveness among Mormons. Much of what they do is directed “toward strengthening the church by conserving its membership, rather than outward toward meeting widely felt social and economic needs.” Although they are “deeply involved in the Chamber of Commerce, local politics, business and the professions, much of their life is still spent in self-contained Mormon groups.” Whether Mormons will be able to adjust to “contemporary pressures, without sacrificing the essence of their distinctive and close-knit culture” is uncertain. “In view of the Mormons’ record of meeting challenges in the past,” Paul thought it was “by no means certain that they [would] fail.”

Even with several important changes in doctrine over the years, Time’s August 7, 1978, profile was still able to present convincing evidence on why the Church would “never blend easily into the religious landscape.” There were, however, encouraging signs. The Church’s “most offensive tenet,” had vanished with President Spencer W. Kimball’s revelation allowing “all worthy males” to hold the priesthood for the first time. This revelation also “solved the dilemma of who would be eligible to use the new temple in racially mixed Brazil.” As a result of President Kimball’s “innovations, new classes and cultures [might] yet penetrate Brigham Young’s mountain-ringed fastness.”

“While the Mormons are definitely not moving toward the American religious mainstream,” Jan Shipps claimed that America might well be mov ing toward them. “Because Mormonism is dynamic and changing,” she told Christian Century readers, “it will never be possible to say with certainty that ‘in Zion all is well.’ Yet things seem to be going along with remarkable equanimity right now.”

Viewing this “quintessential religion” from an equally positive perspective, syndicated columnist George Will in January 1979, lauded the Mormons for making “up the most singular great church to come into existence in the United States.” He extolled them for “triumphing in this world,” while at the same time “turning faith into works.” These “American Zionists,” as Will characterized them, “were and, to an astonishing extent in this homogenizing nation, still as distinctive as the first Americans, the Puritans.”

One of the more insightful articles prompted by the 150th anniversary of the Church in 1980, was written by Kenneth A. Briggs for the New York Times. Briggs viewed the Church as a “burgeoning and influential religion whose members eagerly espouse the traditional values of patriotism and capatilism; a highly respected embodiment of a clean-living, old-fashioned set of principles.”

At the very edge of Mormonism’s “optimism and prosperity,” however, Briggs saw several potential problems; the most obvious of these being the Church’s stand against the equal rights amendment with its accompanying conviction that key roles for women are only in the home. Its “stepped-up efforts to preserve the traditional morals life” were growing increasingly formidable. “For example, one-third of the church [was] now made up of single people over age 25, who do not fit into the ideal image that the church holds up.” This problem was “especially acute among divorced women.” Far more subtle are the pressures produced by the entrepreneurial spirit of Mormons, which critics both inside and outside the Church contended, has “indirectly encouraged greed and unbridled ambition decried by Mormon teachings.”

Also in April of 1980, John Dart of the Los Angeles Times portrayed current Mormons as “‘more American than the average Americans.'” For Dart they perpetuate “in their own circles the culturally homogeneous picture America had of itself in the 1940s and 1950s.” The Mormon desire for acceptance by fellow Americans, he argued, was “motivated more by the desire to gain access to prospective converts than any desire to meld into American society.” Still, confirmed Mormon watchers saw a spirit of independence asserting itself “despite the outward appearance of constant tradition and resistance to change.”

U.S. News & World Report paid tribute to the Mormons twice during the Church’s sesquicentennial year, crediting them with “grappling” quite well with their “growing pains.” In August, James Mann praised them, as their critics had, for the tremendous reception which their message of optimism had received.

Chris Jones and Gary Benson used the May/June Saturday Evening Post to applaud the Church for becoming widely recognized “as one of the fastest growing and energetic religious groups in the world.” Why, the two authors asked, “do the Mormons have a significantly lower cancer rate and fewer heart attacks and debilitating diseases than other Americans? Could it be that family stability, physical fitness, abstinence, hard work and self-reliance are not outmoded virtues after all?”

Describing Mormons with far less respect, Kenneth C. Danforth in the May 1980 Harper’s told of a recent experience in Salt Lake City where every thing was more “firmly in the moral, economic, and political grip of a prudish cult” than any other city in the Western World. Danforth was certainly not the first to recognize the economic prowess of the Church.

The Church’s “highly secretive, largely tax-exempt financial empire,” has long been a source of immense fascination to the media. Much of what the Church has done with its various businesses was appraised by Advertising Age in December 1977 as being subtle but effective. In Salt Lake City it had adopted a “‘hands off attitude in the operation and function of the city.” Instead it worked through its own businesses and was influential in persuading other major companies “to join in revitalizing the downtown area and its overall input into the Salt Lake City economy.”

Looking at the Mormon financial empire far more critically, an article prepared for New West by Jeffrey Kaye credited the Church with wielding “more economic power more effectively than the state of Israel or the Pope in Rome.” At least 50% of what was produced by the Church’s welfare program, Kaye alleged, was being sold on the open market, while the Church at the same time continued to request exemptions from property taxes in California under the guise that the land was being used for charitable purposes.

After surveying the most populated areas of the state, New West found that the Church was paying property taxes on less than a third of its holdings. Exemptions on the remaining two-thirds meant that “$15 million in property taxes that might otherwise be collected never [saw] the state coffers.” For some “it might seem strange, almost slightly blasphemous, to refer to a church as a corporation, but the analogy here is inescapable.” There was no question in Kaye’s mind. The Church was “undeniably corporate.” It owned property “in all fifty states and on every continent abroad.” The confusion inside the church about the size of the Mormon empire “reflected the way the leader ship exercises control.”

As the Mormon kingdom had grown, so also had the wealth which various analysts, journalists, and historians have estimated to be between $3 million and $5 million a day. Calculations by Robert Unger of the Kansas City Times revealed that the Chruch was taking “in $708,750,000 a year—or at least $2 million a day in tithing alone.”

Bob Gottlieb and Peter Wiley placed the Church’s vast economic holdings “on a par with many of the country’s largest corporations.” Included among the Church’s businesses which they itemized for the August 1980 Nation were “four insurance companies; a major agribusiness corporation; a hugh media conglomerate with a book publishing company, book stores, a media consulting company and fourteen commercial TV and radio stations” stretching from New York to San Francisco. Other assets included woollen mills and other manufacturing outlets; a computer company; a major real estate operation; and hundreds of thousands of acres of valuable urban real estate and prime farm land.

With the Church’s growth as a financial power the media has also begun to devote considerable attention to the Church’s increased involvement in the American political process. In November 1978, both the Los Angeles Times and Washington Post felt prompted to identify religion as the dominant issue in Idaho’s gubernatorial election. “Possibly not since John F. Kennedy’s Roman Catholicism was raised when he ran for president in 1960,” reasoned William Endicott, whose story first appeared in the Times and then the Post, “has religion played such a major role in an American political campaign.” It was a campaign in which a “grim-faced Ronald Reagan” peered “from the tele vision screen in a 30-second commercial for Republican gubernatorial candidate Allen R. Larsen” to caution “Idaho voters not to be swayed by the religious issue.”

There were charges that the Church was involved in a conspiracy to take over the state government. And then there were the miners in the north who feared the Mormons “would take away their booze, their gambling” and their women. The irony of the story was that whatever the outcome, Idaho was about to elect its first Mormon governor. But John V. Evans, a former lieutenant governor who moved to the top job when Cecil D. Andrus became Secretary of Interior, was not an active Mormon and so proved to be only a momentary concern after his election.

Focusing on the Mormon influence in California politics, Kerry Drager provided a brief look at the five Mormons serving in the state legislature and then devoted a similar amount of attention to lawmakers in Washington. Drager’s informative July 1980 California Journal article could well serve as a handout on why Mormons have become “involved in political activities, whether it’s running for office, contributing to a candidate, speaking out at a hearing, or merely voting and keeping informed on the issues.”

In the midst of the Church’s sesquicentennial, “prosperity, increasingly ungovernable membership growth, and a swirl of vital, secular influences,” Joel Kotlin’s April 1980 Washington Post story showed how attention had increasingly begun to focus on Ezra Taft Benson, President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. As “heir-apparent to the mantle of president Spencer W. Kimball, the frail 85-year-old titular head of the church, recognized prophet, seer and revelator,” Benson was becoming an ever increasing source of concern to the more liberal among the faithful.

“The Mormon political outlook today,” Nation readers were told by Bob Gottlieb and Peter Wiley in August 1980, “is conservative, probusiness, pro development and on social issues vigorously opposed to women’s liberation and related movements.” The future, however, was less clear. “Beneath this apparent consensus a fundamental debate is taking place which pits the next generation of modern corporate managers against a more virulent right-wing grouping under the leadership of Ezra Taft Benson.”

Benson’s words, the two authors contended, frightened many liberal Mor mons. “With fear and trepidation, the Mormons face the future poised to do battle in a land where they see ‘evil and crime and carnality covering the earth,’ where ‘inequity abounds’ and where ‘there is no peace on earth.'” Expressing similar concern, the Economist thought there are many Mormons whose “consciences would be stretched to the limit by the types of judgments Mr. Benson might make.”

“The Mormon Church is enormously conservative, enormously,” Howard Means observed in the March 1981 Washingtonian, “and well located in the new Republican era. The Mormon contingent in Congress has now grown from ten to eleven with the election of Senator Paula Hawkins in Florida.” Even with “Arizona Representative Mo Udall among its numbers, the contingent has the most conservative voting record of any religious group in Congress.”

Mormons, as Means points out, are well placed in Washington. Senator Jake Garn now directs the Senate Banking Committee and Orrin Hatch serves as chairman of the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee. Richard Richards, the newly crowned head of the Republican National Committee, is a Mormon, as is Terrel Bell, the Secretary of Education. Other Mormons well placed in the Republican Party include David M. Kennedy, once Richard Nixon’s Secretary of the Treasury; former Michigan governor and presidential hopeful George Romney; and Brent Scowcroft, a national security adviser to both the Ford and Nixon administrations.

Means sees “nothing inherently wrong, or unusual” about the Church gaining such political clout, but feels “it is in the person of Ezra Taft Benson—senior apostle of the Mormon Church—that the two forces of political and economic power may well come together to form a test of faith for many Mormons.” Mormons believe “that there will come a day when the Constitution of the United States will hang as if by a thread and that it will be the burden and glory of the Mormon people—the custodians of Christ’s True Church, founded in the Divine Land to rescue it.” Ezra Taft Benson already believes that time has come, and Means quotes him as saying: “Be wary of those so-called political scientists who advocate that the Church restrict itself to moral issues and would bar the living prophets from dealing with political and social issues.” Means concedes that “it is open to question how far Benson would go—or could go—in politicizing the Church should he be come its prophet,” but he has “already given some indication of how far he might go in putting the Church’s vast resources and its three million Ameri can members at the service of the radical right. At least twice he has publicly said that he can foresee the day when Mormons will be directed on how to vote in presidential elections.”

Also well chronicled is Benson’s support of the Freeman Institute, which John Harrington claimed in an August 1980 issue of The Nation, “has become a political force capable of influencing the outcome of elections and legislation on the local, state and national levels.”

The current media image of the Mormons might well be summarized in the New York Times article, “The Mormon Nation,” by Peter Bart, who writes,

While the ubiquitour “moral activists” are hard at work selling their vision of tomorrow’s America, anyone interested in peeking into the new American Dream need look no further than that part of the United States that Westerners call “the Mormon Nation.”

The three million Mormons of Utah and neighboring states have quietly constructed a living laboratory for this new society—the “moral” America of the future. No outsider can travel around the region without noticing that strangers smile at one another, almost everyone has a job, crime is rare, schools are serene, and neighbors pitch in to help those less fortunate. The front-porch friendliness reminds you of an earlier, Norman Rockwell America. . . .

Having painted this benign picture, he goes on: “Moral activists who believe that spiritual leaders would play a bolder role in society would approve of the way things are done in the Mormon Nation. When the Church speaks, people obey.”

Then the reverse image appears. Bart asks, “Is this indeed a better society?” and begins to describe the “serious flaws . . . appearing in the fabric of Mormon life”—psychological problems, especially among women and youth, excessive personal financial stresses, lack of support for the arts, increasing repressive measures applied to dissenters and researchers—in short, an unduly homogenized society: If the Mormon Nation embodies the blueprint for a moral America, many people accustomed to living in a more vibrant, heterogeneous society would surely find it a uniquely uncomfortable place to live.”

Bart, newspaperman and novelist, has dramatized his version of the Mormon nation in a novel, Thy Kingdom Come, described on its dust jacket as a story that “drives home . . . the frightening consequences of the concentration of power in religious leadership and the very real possibilities of its misuse.” This blurb aptly describes the interests of the media as they continue to probe the Mormon story.

[Editor’s Note: For Sources Consulted, see PDF Below, pp. 70–73]

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue