Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 2

Excommunication and Church Courts: A Note From the General Handbook of Instructions

The heads of the Ecclesiastical Council hereby make known, that, already well assured of the evil opinions and doings of Baruch de Espinoza, they have endeavored in sundry ways and by various promises to turn him from his evil courses. But as they have been unable to bring him to any better way of thinking; on the contrary, as they are every day better certified of the horrible heresies entertained and avowed by him, and of the insolence with which these heresies are promulgated and spread abroad, and many persons worthy of credit having borne witness to these in the presence of the said Espinoza, he has been held fully convicted of the same. Review having therefore been made of the whole matter before the chiefs of the Ecclesiastical Council, it has been resolved, the Councillors assenting thereto, to anathematize the said Spinoza, and to cut him off from the people of Israel, and from the present hour to place him in Anathema with the following malediction:

With the judgment of the angels and the sentence of the saints, we anathematize, execrate, curse and cast out Baruch de Espinoza, the whole of the sacred community assenting, in presence of the sacred books with the six-hundred-and-thirteen precepts written therein, pronouncing against him the malediction wherewith Elisha cursed the children, and all the maledictions written in the Book of the Law. Let him be accused by day, and accursed by night; let him be accursed in his lying down, and accursed in his rising up; accursed in going out and accursed in coming in. May the Lord never more pardon or acknowledge him; may the wrath and displeasure of the Lord burn henceforth against this man, load him with all the curses written in the Book of the Law, and blot out his name from under the sky; may the Lord sever him from evil from all the tribes of Israel, weight him with all the maledictions of the firmament contained in the Book of Law; and may all ye who are obedient to the Lord your God be saved this day.

Hereby then are all admonished that none hold converse with him by word of mouth, none hold communication with him by writing; that no one do him any service, no one abide under the same roof with him, no one approach within four cubits length of him, and no one read any document dictated by him, or written by his hand.

During the reading of the curse, the wailing and protracted note of a great horn was heard to fall in from time to time; the lights, seen brightly burning at the beginning of the ceremony, were extinguished one by one as it proceeded, till at the end the last went out—typical of the extinction of the spiritual life of the excommunicated man—and the congregation was left in total darkness.

The excommunication of Spinoza, 1656[1]

I

1. Have your actions influenced members and non-members to oppose church programs, i.e., the missionary program?

2. Have your actions and statements advocated diminished support of church authority?

3. Have you presented false doctrine which would damage others spiritually?

Letter of excommunication to Sonia Johnson, 1979

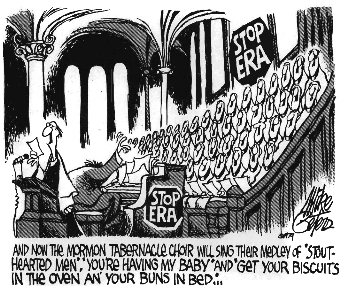

Among the things Mormon brought into the spotlight by the Sonia Johnson affair, perhaps the least well understood was the LDS notion of “excommunication.” To non-Mormons the process seemed, in Phil Donahue’s widely heard characterization, a “medieval”, anachronism. On the Mormon side, while the notion was hardly a surprise, a remarkable ignorance of the criteria and mechanics was generally evident whenever the faithful tried to “explain” what was going on. Even among knowledgeable Mormons, there was little agreement as to whether the “trial” followed the “established Church procedures”—or, for that matter, on what these procedures actually were. Many Mormons “knew” all the answers were to be found in the General Handbook of Instructions, a policy guide issued to all local church leaders by the First Presidency, but very few seemed to have a working knowledge of its contents. One critic, in fact, has charged that the trial of Sonia Johnson was a miscarriage for the very reason that she and her supporters were ignorant of the rules under which they were operating—they had no access to the General Handbook. In this note I will review the relevant guidance provided by the Church in this handbook, for it indeed has become the authoritative guide on church judicial procedures.

Guidance on “transgressions” did not, of course, originate with the relatively recent General Handbooks of Instructions. There was direction on the subject from the very earliest days of the Restoration. A revelation dated February 9, 1831, presently published as D&C 42, probably represents the earliest criteria document. A standard to the present day, it was included in the 1833 Book of Commandments, as well as the 1835 and all succeeding editions of the Doctrine and Covenants. This revelation specified:

Thou shalt not kill; and he that kills shall not have forgiveness in this world, nor in the world to come. . . .

Thou shalt not steal; and he that stealeth and will not repent shall be cast out.

Thou shalt not lie; he that lieth and will not repent shall be cast out.

Thou shalt love thy wife with all thy heart, and shalt cleave unto her and none else.

And he that looketh upon a woman to lust after her shall deny the faith, and shall not have the Spirit; and if he repents not he shall be cast out.

Thou shall not commit adultery; and he that comitteth adultery, and repenteth not, shall be cast out.

But he that has committed adultery and repents with all his heart, and forsaketh it, and doeth it no more, thou shalt forgive;

But if he doeth it again, he shall not be forgiven, but shall be cast out.

Thou shalt not speak evil of thy neighbor, nor do him any harm.

Thou knowest my laws concerning these things are given in my scriptures; he that sinneth and repenteth not shall be cast out.

A clarification later in the revelation further indicated that penitent persons who had “put away their companions, for the cause of fornication” should not be cast out, but that “if ye shall find that any persons, have left their companions, for the sake of adultery, and they themselves are the offenders, and their companions are living, they shall be cast out from among you. . . .”[2]

Guidance supplementary to that found in the Doctrine and Covenants appears to have been conveyed in many ways—in authoritative epistles, by the words of church leaders in general addresses, or through personal correspondence or local visits. While the general handbooks eventually eliminated the need for these latter mechanisms, they still have been used from time to time in recent years. Current handbooks, in fact, specifically provide for contact with the First Presidency for additional guidance on highly unusual cases.

Although a review of nineteenth-century grounds for church courts is beyond the scope of this article, it is important to recall that disfellowship or excommunication was never limited solely to those guilty of murder, theft, lying or adultery. While these were perhaps the most commonly cited causes for such church action, there were other obvious early indications—such as “apostasy,” “murmuring” and “dissension.” With the establishment by a subsequent revelation of the bishop as a “common judge,” and the installation of the high council as an official court of appeal, the practical jurisdiction of Mormon courts soon extended to many mundane, secular considerations, such as personal grievances among the members. Under such circumstances the “restitution” decreed by these courts was often entirely secular, but occasionally more traditional ecclesiastical sanctions were meted out for sec ular failings as well. The First Presidency, for example, once issued a detailed “general Epistle” of guidance to emigrants about to embark for Zion, and backed it up with the warning that “any material departure from the spirit of these instructions will be considered cause for disfellowship from the Church, or suspension from office.”[3] Church secular authority came to a virtual end late in the nineteenth century, and the jurisdiction of its courts was explicitly limited to more purely ecclesiastical matters. Bishops today are instructed not to involve the church court system in the resolution of difficulties between members; under such circumstances the bishops are to function solely as advisers to the parties involved.

The General Handbook of Instructions evolved out of small circulars on tithing issued periodically by the First Presidency late in the nineteenth century. From 1886 on, these were apparently sent each December as “Annual Instructions.”[4] Although not so designated at the time, the 1899 edition in this series, a fourteen-page pamphlet entitled Instructions to Presidents of Stakes, Bishops of Wards and Stake Tithing Clerks, marked the first in the numbered sequence of handbooks which now has progressed to “Number 21.” The next ten “Annual Instructions” after 1899 (“No. 3,” in 1901, was the first to carry a number) dealt almost exclusively with financial matters and, late in the decade, added a little about membership statistics. It was not until 1913, when the Circular of Instructions No. 12 To Presidents of Stakes and Counselors, Presidents of Missions, Bishops and Counselors, Stake, Mission and Ward Clerks and all Church Authorities was issued, that anything approximating a “general handbook” was made available to local Mormon leaders. While this fifty-two-page pamphlet bore little resemblance to the present 123-page 8V2″ x 11″ book, it treated a wide range of topics “in order that there may be uniformity in the methods of conducting the business of the Church and its stakes, wards and missions. . . .” Among its contents was the first section on “Transgressors.”

Before beginning a detailed review of these and succeeding criteria for church courts, several general observations should be made. First, surprisingly little has been said in the handbooks over the years about the purpose of church courts. The implication of the injunction of D&C 42 that certain transgressors should be “cast out” seems to be that a purging or purification of the Church is intended. A punitive function was equally implicit in the denial to disciplined members of certain “privileges”—on a sliding scale, depending on the seriousness of the transgression. While virtually all the handbooks which deal with church courts speak of the “rights and privileges” thus lost, the purifying function was implicit rather than explicit until the most recent General Handbook, which speaks of a requirement to “purge iniquity from the Church.” Related to this, but in fact a different function, is the notion first added in 1960 that (in criminal cases) “the dignity of the Church will be conserved by prompt action.” Within the past few years another function has been cited, without obvious precedent in any previous handbook. This is the notion that church court action facilitated the process of repentance by excommunicating or disfellowshipping transgressors. Where historically—at least within the context of the handbooks—such penalties from the transgressor’s standpoint were entirely punitive, current guidance suggests that debarment also serves an atoning function,, which “allows” or “help[s] individuals [to] repent” more fully than presumably they otherwise could.

A second general point is that, as will be seen, the list of indicted transgressions has grown substantially over the last seventy years. While some accommodation to new social realities is evident in this growth, it is clear that most of the elaboration is one of refinement rather than true expansion. These refinements are almost exclusively in behavioral transgressions or actions which are unacceptable. Unacceptable beliefs, by contrast, have never been subjected to clarification beyond repeated attacks on the “fundamentalist” heresy.

Third, throughout the history of these guidelines local leaders have been granted an over-riding discretionary authority over when church courts are convened, and what penalties are assessed. Despite an alleged policy to the contrary under John Taylor, bishops throughout the twentieth century have been authorized to waive church court action against most, if not all, penitent transgressors. Only murder (as suggested in D&C 42), incest (since 1976) and surgery for sex change (since 1980) have ever been exempted from the local discretionary authority of the bishop; these three now mandate excommunication. Other considerations than the transgression, per se, have become increasingly important in the decision to take action in recent years. Such long established factors as penitence, and the flagrance or persistence of the transgression have been joined (since 1979) by the ecclesiastical office of the transgressor as the major prescribed determinants in nearly all cases. While other, unwritten factors may have further eroded local options in recent years, the handbook nonetheless retains much of the theoretical flexibility it had fifty years ago.

Also of general interest is the enormous increase over the years in the number of excommunications annually, from 55 in 1913 to an average of about 4,500 a year for the six years around 1970.[5] This represents a per capita increase from 1 in 6400 members to 1 in 640. Some of this may reflect only a correction of the “kiddie’dip” missionary excesses of the early sixties, but it can hardly account for a ten-fold overall increase.[6] Given the relative stability of the handbook criteria over the years, and the continued local autonomy, one is tempted to suggest that Mormons are simply more likely to “transgress” these days. Considering the social context in which the modern Church operates, this may be true. I would suggest, however, that a changed perspective on the part of local leaders—reflecting both firmer informal guidance from above, and the new notion that court sanctions have a redeeming function—is also a significant factor.

The initial 1913 statement of guidance on transgressors contained in Circular of Instructions No. 12 was notable both for its parsimony and tolerance:

In cases of transgressors, the laws of the Church as set forth in the Doctrine and Convenants [i.e., D&C 42, quoted above] should be complied with. It is not necessary in all cases that those whose offenses are not generally known shall be required to confess in public. Transgressors should, be dealt with in kindness and with the object of reclaiming them where possible. The bishop should act with the utmost care and discretion in all such cases.

“Certificates of membership” were not to be issued in the case of transgressors, but “[i]f the offender makes satisfactory amends and shows evidence of true repentance, the certificate may be forwarded with such explanations as may be considered necessary.”

The conciliatory tone was entirely intentional, for Joseph F. Smith, then president of the Church, later followed up this theme in both conference address and First Presidency message. “During President Taylor’s time he hated this great sin [i.e., adultery] so much,” Smith observed, “that he made it a rule that if an elder became an adulterer he was cut off from the Church regardless of his repentance; but each case stands on its own merits. There is no precedence.”[7]

It is clear that the section on transgressions in this handbook was not intended as a comprehensive catalogue, for there Had been repeated guidance from the First Presidency by this time that those still entering into polygamous marriages were to be excommunicated, a point nowhere made in the Circular.[8] The handbook did instruct, in a section which came indirectly to grips with the question of apostasy, that when a member “expresses a desire not . . . to be considered a member of the Church, and requests that his name be stricken from the records, such person should be summoned to appear before the bishopric, and if he persists in his desire to have his membership canceled, action should be taken accordingly.”

In 1921, now under the Presidency of Heber J. Grant, a new handbook was published as Instructions to Bishops and Counselors, Stake and Ward Clerks, No. 13. It contained a greatly enlarged treatment of “transgressions,” much of which was said to be taken from “a forthcoming book on ‘Priesthood/ to be published by the Church, and now being written by Elder James E. Talmage, of the Council of the Twelve.”[9] While no explicit list of indications for church courts was included, it cited in addition to the general guidance of Circular of Instructions No. 12:

—cases in which one party accuses another on allegation of personal grievance

—instances of wrong-doing, such as conduct violative of the law and order of the Church, teaching false doctrine, disobedience to Church regulations and requirements, encouraging any or all such evils by example or by open or covert advice . . .

Beyond this, members who refused to appear or answer questions at a church court “without justifiable reasons” or who “openly manifest disrespect toward the court or the proceedings” could be “adjudged by the court as in contempt,” and discipline imposed “ranging from reproof or reprimand to disfellowshipment or excommuncation.”

Beyond the seeming harshness of this latter instruction—which one sus pects was in part brought on by the emerging fundamentalist schism—a compassionate view was still strongly encouraged. In language retained in the following handbook as well, it was stated that cases should be disposed of “according to the publicity already given it.” More specifically, “where persons guilty of adultery and fornication confess their sin, and their transgression is known to themselves only,” there was no need for a trial. A confession to the bishop was sufficient, and “should not be made public or recorded.” If the transgression were more widely known, then confession (without referring to the specific transgression) should be made in the priest hood meeting. If a woman transgressed, this confession was expressed to the priesthood on her behalf by the bishop. The next handbook also added the possibility in some cases for this to take place in Fast meeting. This collective guidance continued through all succeeding handbooks until 1976, when the notion of public confession was dropped.

The fourteenth handbook, issued in 1928 amidst America’s experiment with Prohibition, specified for the first time “transgressions which are ordinarily such as to justify consideration by the bishop’s court:”

—fornication, adultery, and other infractions of the moral law

—liquor drinking

—bootlegging

—criminal acts such as thievery, burglary, or murder

—apostasy and opposition to the Church

Missing altogether was the previous guidance on contempt of court. Perhaps related most closely was a new statement to the effect that the bishopric should consult potential witnesses on “the extent of their knowledge of the facts and their willingness to give the evidence.” If any witnesses object to testifying, “undue pressure should not be brought to bear upon them.”

Additional guidance, apropos that previously given, indicated that “If the transgressor manifest earnest contrition for his fault and shows the real fruits of repentance, he should be forgiven and retain his membership, except as to certain conditions stated in the Revelation [i.e., D&C 42].” Particular concern was expressed that “No records [again, no trial] should be made of minor transgressions of young people who make confession and are forgiven, or of cases of similar character and strictly private nature when so considered by a bishop. . . .” Moreover, “where persons guilty of adultery or fornication confess their sin . . .” and the case was not one of wide notoriety, there was— as noted above—no need for a trial or public confession. Identical advice, always in cases where the transgression was known only to those involved, was to be found in the next three issued handbooks, extending through the fifties.

Guidance similar to that previously set forth was also included on individuals who desired to have their names removed from church records: if efforts “in kindliness and patience” failed to bring them to repentance, they should be excommunicated for “apostasy and at his (or her) own request.” Similar guidance continued throughout all future handbooks. Additional comment, beginning in 1944, specified that those who joined other churches need not necessarily be excommunicated, but that joining other churches was “not approved” and could qualify as grounds for such action.

When the next edition of the handbook was published in 1934 as Handbook of Instructions, No. 15, “drunkenness” and “cruelty to wives or children” had been added to the list of transgressions “ordinarily” justifying a bishop’s court. Attention was “particularly directed to the attitude of the Church with respect to teaching, encouraging, or entering into the practice of so-called plural marriage, statements concerning which have been issued by the First Presidency at various times.” The handbook continued, in language based on a previously issued statement by the Presidency:

Any reported violations of the rule adopted by the Church with respect to this practice should be promptly and diligently investigated; and, if persons are found who, as a result of the investigation, appear to have violated this ruling, or who are entering into or teaching or encouraging or conspiring with others to enter into so-called polygamous marriages, action should be taken immediately against such persons, and, if found guilty, they should be excommunicated from the Church. Local Church officers will be held responsible for the proper performance of this duty.

The transgression list in the sixteenth Handbook of Instructions, which appeared in 1940 under President George Albert Smith, reflected the end of Prohibition but was otherwise unchanged from its predecessor. “Intemperance” was substituted for “liquor drinking, drunkenness, and bootlegging.” That this was to be applied with great restraint was suggested in more detailed guidance given three years earlier: special efforts were to be made to involve “into some activity” the “weak and recalcitrant members who persist in the use of intoxicants;” “The skill of true leadership is shown not in disfellowship or excommunciation, but in conversion.”[10]

Elsewhere in the handbook, a new section appeared related to the changing social context. Local leaders were advised that members “employed as salesmen in state liquor stores, or in any other way . . . engaged in the trafficking of liquor, should not be assigned stake or ward office. The two positions are incompatible.” This ban was continued until 1968 when the twentieth edition of the handbook softened the wording to “cautious consideration should be exercised before persons so involved are called to Church positions.” This remains the current guidance.

Handbook of Instructions, No. 16 also carried expanded instruction on convicted criminals. The two previous handbooks had made brief comments on such cases, emphasizing that “the action of the Bishop’s Court is in all cases a matter of last resort, after every possible effort has been made to bring a transgressor to repentance.” In lieu of this No. 16 explained that conviction in a criminal court was “prima facie evidence of guilt and the bishop’s court is justified in taking action.” This, however, “should be deferred” if the individual “evidence a spirit of repentance and desires to retain his membership.” A slightly more emphatic guideline followed two handbooks later, with No. 18 in 1960: “Persons convicted of crimes in the civil courts should also receive consideration of the Church courts, subsequent to action of the civil courts. . . . Persistent criminals involved in lesser crimes should be handled in accordance with the gravity of their cases.” Any individual so convicted should be asked “to present evidence why he should not be excommunicated.” While repentance, per se, was not mentioned in this specific context, the accused’s right to be present at his church trial was considered potentially legitimate grounds for a postponement “until he can appear.” This policy has continued until very recently.

Finally, the persistence of the Fundamentalist problem was reflected in a considerably expanded discussion in Handbook No. 16 of those still involved in “polygamous or plural marriages,” ending with this emphatic injunction:

Each president of stake and bishop will proceed immediately to correct any situation of the kind described and existing within his jurisdiction. There must be no condoning of or trifling with this rebellious condition which must be brought to an end at once. This is imperative.

The same discussion was carried in the next Handbook of Instructions, No. 17, which appeared four years later, in 1944, and added “deliberate disobedience to [church] regulations” to the previously indicted “apostasy [and] opposition to the Church.” This handbook left the transgression list otherwise unrevised, but did introduce a notable change into the discussion section. To the traditional message on forbearance on private sexual sins was added the observation that “it is difficult to give any set rule for the handling of cases involving moral conduct,” each of which must be considered “on its own merits and according to the seriousness of the offense:”

The prevailing opinion in cases involving young unmarried couples who are obliged to marry is to be as lenient as possible, considering always their future lives and the effect which unnecessary publicity may have upon them. Too severe action often defeats the ends of justice. This would be more harmful to the individuals, their families, and the community than any good which it is hoped to accomplish by drastic measures. If transgressions are known only to the persons involved and they appeal to the bishop of the ward in the spirit of repentance for forgiveness, it is perfectly proper that the case be heard by the bishop of the ward only, who will in wisdom consider the facts and render such decision as his good judgment may dictate. If the bishop feels that they should be forgiven and reinstated to their privileges in the Church, it is his right to take such action and avoid further publicity.

While some of this wording has been deleted, similar or verbatim advice to that just quoted appears in all succeeding handbooks. The next two editions (Nos. 18 and 19) continued to state explicitly that “Bishops have the right to waive Church court action upon proper evidence of genuine repentance,” even “where married couples are involved in sexual sin, and only those immediately concerned know of it.” Both of these handbooks, however, did note that “where endowed persons are involved [the case took on] added gravity and should be dealt with accordingly.” With General Handbook of Instructions, No. 20 (1968), a subtle but significant shift is first evident. While the foregoing text is largely preserved, the reference to married couples is deleted; No. 21 (1976) deletes altogether the explicit guidance on waiving court action in such cases. The tone and central features of the preceding guidelines, however, remains essentially unchanged to the present day.

As an aside, it is notable that beginning with Handbook 17 (the last in the Goerge Albert Smith administraiton), and continuing through the first two editions under President McKay, the introductory First Presidency statement expressly denied that the contents of the handbook were to be taken as an “official statement of Church doctrine.” The latter two of these three also “recognized that there must be flexibility in handling some of these matters and that inspiration and the direction of the Spirit must be sought for and followed.” While local leaders have always been encouraged to seek the help of the Spirit, nothing quite like these observations appeared previously or later. The more recent editions, much like the earlier ones, state flatly, “Herein are stated policies and procedures that officers of the Church should know.”[11]

It was sixteen years before the next revision of the handbook, the first issued under David O. McKay. This edition, entitled for the first time General Handbook of Instructions (No. 18) appeared in 1960. While the language had changed somewhat, the basic list was still very similar to that of the previous three handbooks:

Some sins will require bishops court action and possibly trial by the stake presidency and high council. Others may be handled without taking them to trial provided there is sincere repentance. Transgressions referred to here include sex sins; intemperance; criminal acts involving moral turpitude such as burglary, dishonesty, theft, murder; apostasy; open opposition to the rules and regulations of the Church; cruelty to wife or children; and similar matters of a serious nature.

Aside from the open-ended concluding phrase, the only significant addition to previous guidelines is the explanatory phraseology characterizing suspect criminal acts as those “involving moral turpitude.” In addition, while not really breaking new ground, a new section in this edition brought together previous guidance on “Cases Where No Court Action is Required.”

Two other editions of the General Handbook were issued during the McKay administration. Number 19, in 1963, was essentially identical to its predecessor on the points here under discussion. General Handbook of Instructions, No. 20, however, published in 1968, once again expanded the list of cases (“but . . . not limited to”) to be handled by church courts. Now also included were “homo-sexual acts.” “Cruelty to spouse or children” replaced “cruelty to wife or children.” “Open opposition to the rules and regulations of the Church” was expanded to incorporate “open opposition to, and deliberate disobedience of” such rules and regulations. The Fundamentalist challenge was collapsed to a concise category indicting those “advocating or practicing so-called plural marriage.” And, finally, there was a new proscription of “any un-Christian like conduct in violation of the law and order of the Church.”

The most recent General Handbook of Instructions, No. 21, issued in 1976, is more extensive and explicit on the grounds for church court action than any previous handbook. These were specified as follows:

1. Open opposition to and deliberate disobedience to the rules and regulations of the Church.

2. Moral transgressions, which include but are not limited to—

a. Murder (grounds for mandatory excommunication).

b. Adultery.

c. Fornication.

d. Homosexuality.

e. Incest (grounds for mandatory excommunication).

f. Child molesting.

g. Advocating or practicing plural marriage.

h. Misappropriating or embezzling Church funds.

i. Intemperance.

j. Cruelty to spouse or children.

k. Unchristianlike conduct in violation of the law and order of the Church.

1. Other infractions of the moral code.3. When a member is convicted in courts of the land of a crime involving moral turpitude, such is prima facie evidence justifying excommunication by a Church court. Regular Church court procedures should be instituted and appropriate disposition made, but not until there has been a final judgment entered in the criminal action.

4. A request by an individual that his membership be withdrawn . . .

5. Parents requesting that names of unbaptized children be removed from Church records.

6. Where parents request in writing that the names of their baptized minor children be removed from the records of the Church. . . . [but only after specific guidance from the First Presidency on each case].

“Inactivity in the Church” was not “in and of itself” sufficient reason to summon a member before a court, and even “joining another church” was not “in itself grounds for excommunciation or disfellowship.”

So far as the standard endorsement of local flexibility was concerned, guidance was reduced to the long-standing comment that “young unmarried people involved in moral transgressions who manifest a sincere spirit of repentance” should be given special consideration. Nonetheless only two items in the now extensive list were explicitly labelled “grounds for mandatory excommunciation”—itself a phrase newly added to the discussion. That other items were not all to be viewed in an identical light was suggested by a requirement that transgressions in several categories required First Presidency approval before excommunicated individuals were to be readmitted (by rebaptism) to the Church; otherwise this could be handled locally. Singled out were murder, incest, misappropriation or embezzlement of church funds, advocating the teaching of, or affiliating with, apostate sects that practice plural marriage, or excommunication while serving as a full-time missionary or in a few prominent positions in the church leadership (“such as” mission or temple president, member of a stake presidency, patriarch, bishop or high councilman).

While the 1976 edition of the General Handbook is the most recent, it is not the last word on the subject. There have been, to date, five supplements to this handbook; the most recent, printed in October 1980, is a revision of the handbook chapter on “The Church Judicial System”—a revision, in fact, of a completely revised supplemental chapter issued just the year before, in November 1979 (i.e., the relevant chapter in the 1976 handbook has been replaced twice in the last two years). These revised chapters provide local leaders with by far the most lucid and thorough discussions to date, and first make explicit the “redemptive” function of court sanctions. Among the changes will be seen a clearer distinction between when courts may and must be convened, as well as new instructions on inactives and criminals. Those involved in abortion are added to the list of members who “may [“should” in 1979] be brought before a Church court where the facts can be weighed,” and those undergoing “a transsexual operation” also are now [1980] to be brought to trial—as well as LDS doctors performing either of these procedures. The basic guidance on optional and mandatory cases is presented as follows in the 1980 chapter revision:

Church courts may be convened to consider—

1. Open opposition to and deliberate violation of the rules and regulations of the Church (including associating with apostate cults or advocating their doctrines).

2. Un-christianlike conduct.

3. Serious transgressions, including adultery, fornication, abortion, homosexuality, lesbianism, child-molesting, cruelty to spouse or children, theft, embezzlement of Church funds, misuse or embezzlement of other people’s funds, and any other serious infraction of the moral code.

Church courts must be convened when a serious transgression has been committed and one of the following circumstances exists:

1. At the time of the transgression the transgressor held a prominent position of responsibility in the Church: general Church auxiliary officer or board member, Regional Representative, mission president, temple president, patriarch, stake president, stake president’s counselor, district president, district president’s counselor, high councilor, stake auxiliary president or counselor, bishop, bishop’s counselor, branch president, branch president’s counselor, or full-time missionary. (Should there be any questions about full-time Church employees, including seminary and institute personnel, presiding officers should write to the Office of the First Presidency for clarification.)

2. The transgressor is guilty of murder.

3. The transgressor is guilty of incest.[12]

4. A transsexual operation has taken place.

5. The transgression is widely known.

6. The transgressor poses a serious threat to other Church members.

7. The transgression is part of a pattern of repeated serious wrongdoings, especially if prior sins have already been confessed to priesthood authorities.

8. The Spirit so directs.

Additional clarification, which should be consulted directly, explains that inactive members should not be called to court unless they are “influencing others toward apostasy” or “make a written request at [their] own initiative” for excommunication. By contrast, new guidance is also given that members who have joined other churches “should be cited and brought to a Church court.” In a further clarification on criminal cases, local leaders are advised that conviction by a criminal court does not automatically require action by a church court, though the matter should be weighed “carefully” and a decision made based on “the seriousness of the offense.” “Murder” (and incest and, now, transsexual surgery) still mandates excommunication, but the term is clarified to exclude come “circumstances .. . [in which] the death was caused by carelessness, self-defense, defense of others, or [there were] other mitigating factors. … ”

Finally, in addition to the long-standing counsel on special care “with young, unmarried Church members who have been involved in moral transgressions . . .” a new section advises that when “a member voluntarily confesses a serious transgression committed in the past and his conduct in the intervening years demonstrates full repentance, a Church court need not be convened in most instances.” However, in cases of “recent sin” the “confession may not remove the need for a court,” indeed “it is possible to use information obtained through a member’s voluntary confession as the basis for Church discipline.”

The replacement chapters also give much greater attention to the transgressions which require additional action after church courts have rendered their verdict. As was the case in 1976, those excommunicated for incest, embezzlement of church funds, involvement with fundamentalist/polygamist groups, or while serving in a prominent position of leadership all still required First Presidency approval before rebaptism.[13] As of 1980 this is also required before reinstatement even if such individuals were only disfellowshipped (a requirement previously unnecessary except when missionaries were involved). Especially notable has been the evolution of what constitutes “leadership” status requiring such extraordinary action. Transgressions by missionaries have long received special attention, but no handbook prior to number 21 carried comparable guidance on other assignments. Handbook 21, as noted above, specified that those excommunicated while patriarchs, mission or temple presidents, bishops, high councilmen, or members of a stake presidency, all required special approval before rebaptism. The 1979 replacement chapter stated that all of these—plus bishop’s counselors—must also be taken to a church court in the event of a serious transgression, as well as obtain special permission to be rebaptized if they are excommunicated. The 1980 replacement chapter extends this considerably, adding to the list general church and stake auxiliary leaders, district and branch presidencies, and—in the case of rebaptism—full-time church employees. Additionally, the requirement for First Presidency approval, as noted, is extended to those disfellowshipped as well as those excommunicated.

Beyond this, the 1980 guidelines for the first time made explicit the situations in which “no readmission to the Church is possible.” The first of these, murder, had been designated by D&C as a condition for which there was “no forgiveness,” and this implication is evident in all handbooks since 1960. Much more surprising was the second specified situation: “In cases of .. . transsexual operations, either received or performed, .. . no readmission to the Church is possible.” Indeed, “transsexual surgery” has brought forth the most extensive handbook proscriptions to date. In addition to the sanctions specified against members, “otherwise worthy” investigators who have already “undergone transsexual operations may be baptized . . . [only] on condition that an appropriate notation be made on the membership record so as to preclude [them] from either receiving the priesthood or temple recommends.”

Thus, as noted at the outset, unacceptable behavior has been defined by the Church with increasing clarity over the years. More specific terms have been introduced in place of what initially was a rather broad guideline, and some of these terms have been explicitly defined. No comparable development can be seen in the area of intellectual or doctrinal “heresies” or “apostasy,” excepting only the fundamentalist heresies so consistently condemned over the years. This is not to say that Mormons are doctrinally unrestricted, for there is nothing in the handbooks to prevent terms like “apostasy” or “opposition to” rules and regulations from being applied to non-fundamentalist heresies. While no statistics are available on this question, my impression is that “liberal heresies” are rarely dealt with in church courts. In part this is probably because extreme “liberal heretics” (for want of a better term) generally just drop quietly out of the Church, disappearing into the anonymous ranks of the “inactives.” Less extreme deviation of this sort is most often responded to in more subtle ways, such as restricting opportunities to serve in leadership positions in local congregations or stakes. Also relevant, no doubt, to the lack of church action against perceived liberal “heresies” is the lack of any real definitions of “orthodoxy” within the Church and, by extension, any definition of unacceptable “unorthodoxy.” Where “apostates” have seemed able to attract the attention of local church courts most often has been instances in which they have publicly attacked the authority or integrity of the church leadership. Even here “style” seems to be important. In a real sense it is not so much what is believed as how this belief is expressed that seems to matter most.

II

The guidance given on the actual conduct of church courts has varied little over the years. The precedents are found in two sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, both of which appeared in the first edition in 1835. One, a revelation dated August 1,1831 and currently published as D&C 58, had appeared as well in the Book of Commandments in 1833. This revelation designated a bishop “a judge in Israel… to judge his people by the testimony of the just, and by the assistance of his counselors, according to the laws of the kingdom which are given by the prophets of God.” The second precedent, currently found in D&C 102, is taken from the minutes of the organization of the high council in Kirtland in February, 1834. These minutes described the procedures to be followed in cases brought before the high council (e.g., on appeal from the bishop’s court, or in excommunication proceedings against someone holding the Melchizedek priesthood).[14]

Presumably because of the detail provided in the Doctrine and Convenants, the handbooks have said very little about high council courts. Until Handbook of Instructions, No. 16, essentially no mention was made of the subject at all. Since then the handbooks have simply summarized or referred readers to the relevant portions of D&C 102. For these reasons and because a high council trial was not part of the Sonia Johnson case which prompted this review, the specified procedures will be discussed only briefly.

In essence, a high council when presented with a case, first decides whether it “is a difficult one or not.” Depending on the perceived degree of difficulty, either 2, 4, or 6 of the 12 high councilmen are “appointed to speak” on the case. Half of the total council (including half of the appointed speakers) are directed “to prevent insult or injustice” to the accused, but none is to adopt an adversarial stance on behalf either of accused or accuser. The evidence (e.g., proceedings of a previous trial) is presented, following which

—”the councilors appointed to speak before the council are to present the case, after the evidence is examined, in it’s true light. . . and every man is to speak according to equity and justice.”

—”in all cases the accuser and the accused shall have a privilege of speaking for themselves before the council, after the evidences are heard and the councilors who are appointed to speak on the case have finished their remarks.”

—the president (now the stake president) then gives his decision and calls “upon the twelve councilors to sanction the same by their vote;” if a councilor can demonstrate an error the case theoretically is reheard, but dissenting votes are explicitly discouraged. In no instance is the high council in a position to “veto” the decision of the stake president. If during a reevaluation “additional light” is shed on the case, “the decision shall be altered accordingly.”

—while no longer emphasized, it was originally further specified that “in case of difficulty respecting doctrine or principle, if there is not sufficiency written to make the case clear to the minds of the council, the president may inquire and obtain the mind of the Lord by revelation.”

—there is also a provision for appeal of the high council court, to be made to the First Presidency who may choose to review the decision if circumstances seem to warrant.[15]

Much more attention has been devoted in the handbooks to the procedural aspects of the more common bishop’s courts. Even so, these have changed surprisingly little from the guidelines first included in the Instructions to Bishops and Counselors, Stake and Ward Clerks No. 13, in 1921. Rather than address these changes chronologically, however, I will summarize in detail only the policy set forth in General Handbook of Instructions, No. 21, which was in effect at the time of the Sonia Johnson trial. Variations from this 1976 edition, either in previous handbooks or the more recent supplements, will be noted where relevant. Ironically this particular handbook, while including a more extensive (and completely rewritten) discussion of church courts than anything to date, was less helpful in many ways than previous editions. Several significant lapses were corrected in the recent replacement chapters.[16]

Bishop’s courts can be convened in two basic ways. In the first, which used to be termed loosely, “on complaint and summons,” an individual brings charges agaisnt a member of the ward who in turn is summoned before the court by the bishopric. In the second, previously referred to as “by citation,” there is no specific accuser, and the case is initiated by the bishopric alone. This latter action, as explained in the thirteenth handbook, was to be used “in instances of wrong-doing, such as conduct violative of the law and order of the Church, teaching false doctrine, disobedience to Church regulations and requirements, encouraging any or all such evils by example or by open or covert advice—in none of which is any one member of the Church personally injured or aggrieved more than others.” Since under such circumstances, “[i]t may be that no person comes forth as the accuser,” the bishop could appoint two holders of the Melchizedek priesthood to investigate and make the complaint; or, the bishopric may issue the citation directly. Current handbooks no longer emphasize the distinction between these two approaches; and once initiated, the action in both cases is the same.

The summons to the accused is served personally by two members of the Melchizedek priesthood. (In the Johnson case, it was the two counselors in the bishopric). The summons states the time and place of the bishop’s court, but does not detail the charges. The 1976 handbook, number 21, for example, provided a suggested format which proposed only the wording, “for investigation of conduct in violation of the law and order of the Church.” The Johnson case has been faulted by many because only vague charges were announced prior to the trial, but one has to go well back in church history to find a recommendation for anything but a vague pre-trial statement of charges.

The original handbook guidance in 1921 proposed that a summons include a brief “statement of important points to be inquired into, or investigation to be made,” but left only two lines in the suggested format for this to be accomplished. In I960, Handbook No. 18 suggested that in cases in which “the wrong doing is well known, and no eyewitnesses are available, and some of the evidence must be obtained by direct questioning in a trial,” that the summons state the charges as “un-christianlike conduct” or “apostasy.” General Handbook of Instructions, No. 20, in 1968, stated clearly that the summons should not “contain specific charges,” and essentially the same point is made in the recent replacement chapters for Handbook 21 (“should not include any details or evidence”). Perhaps in response to some of the same types of questions raised in the Johnson case, these new chapters also suggest that those serving the summons have sufficient knowledge of the case “that they could make a simple explanation to the accused if necessary” to allow preparation of a response and the location of suitable witnesses.

Another criticism frequently heard in the Johnson case was that inadequate preparation time was allowed between the summons and the trial. As reconstructed elsewhere, the summons arrived late in the evening on November 14 with the trial scheduled just over two days later. Johnson requested an extension to December 1, and was granted a postponement until November 27. Reportedly at the direction of the stake president, this extension was cancelled and the trial convened on the 17th as originally scheduled. On further appeal at that time, the court allegedly was transformed into a “pre trial planning session,” and the originally requested extension to December 1 eventually granted.[17]

As irregular as this may sound, there was no explicit guidance in Handbook No. 21 which directed to the contrary. The preceding seven handbooks, back to 1928, had indicated that if the accused could not prepare his defense adequately before the set trial date, he should be allowed a “reasonable” extension, but this point was not again made in 1976. While one presumes that the intent was still there, it is perhaps more important to note also that throughout all the handbooks, the final judge in such matters was the bishop himself.

The bishop’s “court” is comprised of himself and his two counselors, any of whom may chose to disqualify himself. If the bishop disqualifies himself, the case moves directly to the high council; otherwise, under Handbook 21, the disqualified counselor is replaced by the bishop with a member of the ward holding the Melchizedek priesthood. The accused may object to the personnel in the court, in writing, which objection is ruled on by the stake president. Historically the stake president could choose to transfer the case to another bishopric within the stake, but since 1960 the only specified option is for the high council to take original jurisdiction (which it also may chose to do in any case within the stake).

In the Johnson trial, the first counselor had disqualified himself and was replaced by a high councilman from the ward. Historically, there was a requirement that the replacement be a high priest (Handbooks 13 through 20), who for a period of eight years could not be a member of the high council (Handbooks 18 and 19). The current, replacement chapter guidance does not prohibit high councilmen, but again requires appointees be high priests. Sonia Johnson also asked that the high council take original jurisdiction in her case, but they chose not to do so.

From the earliest handbook instructions, there has been a continuing requirement that the ward clerk (or someone appointed in his place) make a complete record of the proceedings, including the essentials of the testimony of all witnesses. Since 1976, the handbook has authorized him to use a tape recorder to assist in this task. The accused, however, can object to the use of the tape recorder, but once again, the bishop makes the final ruling. A major problem reportedly developed in the Johnson case when she asked to make her own tape recording. This ultimately was resolved by the bishop ruling that this could not be allowed. Although no specific guidance was given on this point in Handbook 21, it is relevant to note that ever since Handbook 18 emphatic instruction nas been given that under no circumstances was a copy of the transcript of a trial to be given to the accused (or accuser). The intent was therefore clear, and as with other procedural questions, the bishop seems to have implicit authority to rule on these issues without further consultation.

When the trial actually begins, the bishop states the charges, to which the person pleads either innocent or guilty. (The hearing may proceed in the absence of an accused who fails to appear without sufficient justification). If guilt is confessed, the court can inquire further into the circumstances and then render a decision. If the accused pleads innocent, the case continues as discussed below.

The accuser (or, as in the case of Sonia Johnson, the bishopric) testifies first, followed by all of his witnesses. The accused may cross-examine each witness, and the court may both direct questions and cross-examine. Then the accused testifies, followed by his witnesses, with both direct questions and cross-examining by the court.[18] Ordinarily only church members are allowed as witnesses, a point again decided by the bishop. Witnesses are admitted to the proceedings individually (until 1968, the bishop theoretically could chose to allow all witnesses to be present for all testimony), and while they are waiting to testify, they are instructed (again, since 1968) not to discuss the case with other witnesses awaiting their turns.

A point of frustration expressed by several of the witnesses in the Johnson case was that they were barred from “mentioning ERA.” Whatever one’s feelings about the judgment of such a ruling, it is again well within the specified authority of the bishop. The very first handbook to deal with the subject stated clearly that the bishop had final authority on the admissibility

of evidence, and this has never changed. Handbooks 18, 19 and 20 all instructed that evidence should be “relevant, competent, and material,” and that it was the church member and “not the church doctrine” that was on trial. General Handbook of Instructions, No. 21 broadened this to “It is the Church member, not the Church that is on trial.” One witness in the Johnson trial was said to have been “reprimanded” several times for continually bringing up the ERA. A reprimand or dismissal from the proceedings appears to be the limit to the sanctions available to the bishop under such circumstances. By contrast, as noted earlier, the first handbook to address the subject in 1921 specified that those in contempt of court could be reproved, reprimanded, disfellowshipped or excommunicated. The notion of contempt of court was dropped altogether in the following handbook, which also made it clear (still implicit today) that “undue pressure” should not be brought to bear on witnesses who did not wish to testify. A final point relating to the testimony of the witnesses in the Johnson trial was the bishop’s decision to impose a IV2 hour time limit on the December 1 proceedings. Although his decision was widely criticized after the fact, there is not now, and never has been any handbook guidance on the subject, pro or con. As ever, the broad discretionary authority given to the bishop would seem to allow a decision of this sort, if the intent were to limit testimony perceived to be redundant. The entirely arbitrary imposition of such a restriction presumably would be grounds for a dissenting vote by a counselor, or a rehearing of the case, but only if a reviewing body concluded that the outcome of the case had been materially affected.

Having heard all the evidence, the court can render its decision directly, or it can defer a decision for a short time and adjourn. The final decision is reached by the bishop alone, who privately seeks the “sustaining” vote of his counselors. Handbook 21 makes no explicit provision for the counselors to do otherwise, but the new chapters recently issued states that the bishop’s decision should be sustained “unless they feel that the decision creates a serious injustice.” These chapters further indicate that the decision “need not be sustained unanimously to be valid. The bishop is the judge. Any differences of opinion should be resolved, if possible, and must be kept confidential.”

There has been some variation in the foregoing advice in previous handbooks. Initially, Handbook 13 had specified that at least one counselor had to sustain the bishop, or the case was to be retried or referred to the stake president. In 1940 Handbook 16 indicated that the decision had to be unanimous to be “fully acceptable;” otherwise it was to be retried or referred to the stake presidency for determination “as to further procedure.” It was nonetheless emphasized that the decision was solely to be made by the bishop; the vote of the counselors was to “sustain” this decision. Although the wording changed somewhat, the same basic instruction was given until 1976, when Handbook 21 modified the instructions, as noted above.

When the final decision is deferred, most handbooks, including number 21, seemingly have required that the court reconvene at a specified date to announce the decision. There is some ambiguity over the years, however, and other handbooks would seem to suggest that a second requirement— that the written decision be delivered as soon as possible to the accused— fulfilled this obligation. Written notification can be accomplished by a letter sent via two Melchizedek priesthood holders (as in Johnson’s case) or by registered or certified mail. Beginning with Handbook 21, local leaders were instructed to announce those excommunicated or disfellowshipped in local ward (or stake) priesthood meetings. Details of the cause were to be given only in cases such as “apostasy” in which members ostensibly are to be “warned” about the disciplined individual.

The principal options open to the court, should it find the accused guilty, have been disfellowship for an unspecified period of time (a minimum of a year has been suggested), and excommunication.[19] To these the latest guidance adds “probation,” a lesser sanction previously mentioned only in passing. There no longer appears to be yet another option specified in all handbooks previous to 1976: public confession in lieu of a trial. Bishop’s courts can disfellowship any ward member brought before it, but can excommunicate only women, and men not holding the Melchizedek priesthood.[20] In the past Melchizedek priesthood holders were disfellowshipped and referred on to a high council court, which does have the authority to excommunicate. In recent years the high council generally assumes original jurisdiction in these cases. The actual sanctions implied by these various decrees have been clarified (if not added to) over the years. The restrictions cited below are drawn principally from General Handbook of Instructions, No. 21 and the recent replacement chapters.

Contrary to the popular, non-Mormon perception of these terms, neither excommunication nor disfellowship implies banishment from a Mormon congregation. Handbook 17, in 1944, advised specifically that such individuals “should not be avoided or persecuted. . . . They should be dealt with kindly and prayerfully, in the hope that they may turn from their mistake and receive again the full privilege of Church membership.” Similar guidance continues to the present day. Handbook 21, for example, encouraged local leaders to take a special interest in working with such individuals, and provided that home teachers continue to visit “disciplined” members.

A disfellowshipped member temporarily (but not necessarily “briefly”) cannot participate in “the full program” of the Church. Specifically prohibited are partaking of the sacrament; holding office; attending leadership meetings; speaking, praying or “otherwise participating] in” any church meetings; attending the temple; or voting to sustain church officers. Expressly authorized is attendance at all regular meetings including priesthood (first authorized in 1980), the payment of tithes and offerings; and (if endowed) continued use of temple garments. “[U]pon evidence of sincere repentance, full compliance with the conditions imposed by the court, and a sufficiency of time to prove worthiness,” a disfellowshipped member may be reinstated, but only by the court originally passing sentence (not necessarily the same personnel) or a court “having superior jurisdiction.”

Excommunication is “complete severance from the Church.” All proscriptions noted in cases of disfellowshipment apply (attendance at priesthood is now authorized), and additionally tithes and offerings are not accepted from excommunicated individuals—although beginning in 1980 these could be paid “through a member of their immediate family who is in full fellowship.” Excommunicants also are not authorized to wear temple garments. If “found sufficiently repentant and worthy,” an excommunicated member—with the exceptions previously noted—can be rebaptized, but only with the concurrence of the excommunicating court (or, in some instances, the president of the stake in which it took place). Certain grounds for excommunication (and, since 1980, for disfellowship), as noted in the first section of this essay, also require the approval of the First Presidency before rebaptism can be authorized. In all instances, First Presidency approval is required before “the restoration of [temple] blessings” to previously excommunicated persons. (Such blessings are never “lost” by those disfellowshipped.)[21]

“Probation” involves a specified, temporary restriction on a member’s privileges, and is applied in cases where “the evidence does not seem to justify disfellowship, but it also does not warrant exoneration.” This sanction can also be applied by the bishop without convening a court. Insufficiently penitent members may still be disfellowshipped by a subsequent court; simi larly, disfellowshipped members later may be excommunicated as well.

A member found guilty in a bishop’s court may appeal the decision—and presumably (but not explicitly) the sentence—through the bishop to the stake president. Under these circumstances, the options—which have been spelled out in some detail since Handbook of Instructions, No. 16, in 1940—are as follows:

—if the testimony appears sufficient, the high council simply reviews the case and either affirms or modifies the decision of the bishop’s court.

—if the testimony appears insufficient, they may rehear the case them selves.

—or, especially if there seems to1 have been some basic flaw in the original proceedings, they can direct that the bishop’s court rehear the case.

In the Johnson case, an appeal was made, and the case was reviewed by the high council, who affirmed the ruling of the bishop’s court. A further appeal to the First Presidency led to a decision that no further action was required.

In summary, while critics have accused the bishop in the Sonia Johnson case of having been the accuser, prosecuting attorney, witness and judge, in so doing he followed years of rather consistent guidance on church courts. Where some rare deviations from traditional guidelines aie evident in the case, the actual handbook then in effect—General Handbook of Instructions, No. 21 —can be shown to have departed from the previous language on the subject. Generally speaking, this variance was in the direction of less guidance or greater ambiguity, and much of this has been modified again in a subsequent supplement which regains the clarity of earlier guidelines.

Given the broad discretionary authority of bishops in such circumstances, one might argue that a different, perhaps less traumatic, course could have been followed. Previous handbooks, for example, suggest that there should have been less hassle over the delay requested in the trial date. Additional time could as well have been allowed for testimony during the trial itself. Final authority in such matters nonetheless rests, as noted repeatedly above, with the bishop himself, and it is very doubtful that a more elegant legal process would have changed the outcome. Within the church judicial system, the procedural subtleties are of little consequence in comparison to the per sonal judgments and “inspiration” of the presiding authority.[22]

If fault is to be found with the details of this case, it might better be directed at the ill-defined criteria and logic inherent in the evaluation of non behavioral transgressions. It is a relatively easy matter—conceptually, at least—to establish whether a member is guilty of adultery, spouse abuse or embezzlement. “Apostasy” and “opposition” to the order of the Church are entirely different matters.[23] Before they can be assessed in church courts, definite lines have to be drawn, a process which at present is at best quite awkward, and more typically very inconsistent. For historical reasons, as noted earlier, such lines as exist are found only on the fundamentalist edge of Mormon orthodoxy. Notwithstanding the personal tragedy of the Johnson case—which one expects includes the bishop as well—I would guess that a poll of members along the frontiers of Mormon orthodoxy would overwhelmingly oppose further defining such lines. “Private heresies,” to use Sterling McMurrin’s apt description, still don’t disqualify most people from good standing, and one hopes this will always be so. Aggressively public heresies, by contrast, will probably continue to bring forth rare but painful episodes such as that of Sonia Johnson. Painful, because of the naive hope that imprecise definitions offer some protection after the trial begins; rare, because the same imprecision makes it unlikely that the Church will seek such individuals out—at least not before they long since quietly have withdrawn on their own.

[1] As quoted in Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy.

[2] A Book of Commandments for the Government of the Church of Christ (Zion, 1833), Chapter XLIV, verses 1-25, and Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (Kirtland, 1835), Section XIII, verses 6-7, both contain essentially identical wording to the present text quoted.

[3] “Fourteenth General Epistle of the Presidency . . .,” December 10, 1856, as quoted in James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, 1965-1975), 2:201.

At the non-secular extreme might be placed the following from Brigham Young: “In regard to the law of tithing, the Lord has given the revelation I have already referred to, and made it a law unto us, and let all who have gathered here and refuse to obey it, be disfellowshipped; and if a man will persist in breaking the Sabbath day, let him be severed from the Church; and the man that will persist in swearing, cut him off from the Church, with the thief, the liar, the adulterer, and every other person who will not live according to the law of Christ . . .” Journal of Discourses 10:285, November 6, 1863.

[4] Clark, op.cit., 3:102-104, quotes the first of these at length. He also includes the full texts of the succeeding circulars issued in 1889 (2: 179-183), 1897 (2:290-293), 1898 (2:306-309), 1899 (2:320-323), 1900 (2:328-333), and 1901 (3:14-16).

[5] The figure for 1913 was announced by President Joseph F. Smith in General Conference the following spring, and refers only to stakes. Conference Reports, April (4), 1914, p. 6. The more recent data was provided to me several years ago from the Presiding Bishop’s Office, and includes missions as well as stakes.

[6] I have not seen figures for the early sixties or the mid-seventies, so cannot rule out an atypical bulge during the years for which I have data. I have personal knowledge of rather extensive, but geographically localized, excommunications around 1970 of children baptized into the Church under suspect circumstances during the early sixties.

[7] As quoted in Clark, op.cit., 5:12, from a talk April 8, 1916.

[8] Ibid., quoting statements from 1904 (4:85), 1910 (4:217-218) and 1911 (4:227).

[9] So far as I have been able to ascertain, this book was never published.

[10] As quoted in Clark, op.cit., 6:25-27, from a First Presidency statement published in 1937. It is interesting to note that temple recommends under President Heber J. Grant ostensibly required that holders “keep the Word of Wisdom,” but under George Albert Smith—as reflected in this 1940 handbook—they rather had to “observe the Word of Wisdom or express a willingness to undertake to observe the Word of Wisdom . . .”It was not until the 1960 handbook that this language was changed to a flat requirement to “observe the Word of Wisdom, abstaining from tea, coffee, tobacco, and liquor.”

[11] Quoted from the twentieth handbook; number 21 differs slightly.

[12] Defined in the first replacement chapter in 1979 as “sexual relations between a parent and a natural, adopted, foster, or step child.” The new chapter in 1980 added, “A grandparent is considered the same as a parent.”

[13] First Presidency approval is also required for those whose cases they previously have reviewed and modified to require excommunication.

[14] Book of Commandments, Chapter 59; and D&C (1835) 15 and 5. A number of other sections of the Doctrine and Covenants are often quoted in discussions of church courts or transgressors, but those cited in the text are the only literal antecedents of the specific guidance in the handbook.

[15] Handbook 21 specified that the six high councilmen not directed to “prevent insult or injustice” to the accused “stand in behalf of the Church.” No previous or subsequent handbook guidance makes this point, nor does the Doctrine and Covenants. In practice the instruction on the high council courts given in the D&C is not altogether clear. The most recent guidance (1980) finally tells these courts to follow the same procedure “as outlined for a bishop’s court… to the point where all relevant evidence has been presented.” As a practical matter, there is generally open discussion among the high councilmen thereafter, with the designated speakers addressing only the question of whether things have been presented fairly.

[16] Examples are noted in the text. Perhaps the most conspicuous error was in the interpolation of inappropriate guidance from high council trials into that of the bishop’s court. See paragraph “7” under “Trial Procedures.”

[17] For a reconstruction of the events immediately before and during the trial, see Linda Sillitoe and Paul Swenson, “A Moral Issue,” Utah Holiday, Volume IX, Number 4, pp. 18ff (January, 1980). All subsequent references to specifics of the trial are taken from this article.

It is said that at the time the stake president refused the initial request for an extension that he also requested that Johnson’s temple recommend be returned. While this normally would not have been done until after the court proceedings, bishops and stake presidents do not need court action to cancel a recommend if they feel circumstances warrant.

[18] This wording is essentially identical to that of Handbooks 13 through 19. Though expressed more broadly since then, the sequence is the same.

[19] At no time has specific handbook guidance been given as to when one or the other of these options is most appropriate, excepting the cases which require mandatory excommunication and the notation that Melchizedek priesthood holders cannot be excommunicated by a bishop’s court.

[20] Within a mission, a branch president may be appointed as the presiding officer in an “elders’ court” comprised of three men who hold the Melchizedek priesthood. This court follows the procedures of the bishop’s court, but has the “authority to excommunicate any member in its jurisdication”—at least since 1979.

[21] According to current guidelines there is theoretically no Temple “blessing” for which a sufficiently contrite individual eligible for rebaptism cannot eventually again also become eligible. Handbook 21 had specified that those excommunicated for adultery, whose families have broken up as a result, could not later be sealed to the individual with whom the adultery took place. The recent replacement chapters, however, add “unless it is authorized by the President of the Church.”

[22] Handbook 21 had somewhat misleadingly asserted that church courts “generally follow established legal procedings in courts of law to establish facts and arrive at the truth.” The 1980 replacement chapter more accurately replaces this with, “When a Church court is convened it should be remembered that it is an ecclesiastical proceeding only and that the rules and procedures applicable to the courts of the land do not necessarily apply.” Apropos this, the chapter ends, “In all instances, the First Presidency has the right to make exceptions to any Church court procedures as may be required by unusual circumstances.”

That there are relevant secular constraints, nonetheless, is clear from the following guidance for those investigating accusations against ward members (1979 and 1980): “They should be instructed not to use questionable methods. For example, electronic surveillance devices, hidden cameras or tape recorders, or telephone ‘buggings’ must not be used; nor is it appropriate for Church leaders to hide around members’ homes. Such methods could subject the Church and local priesthood leaders to legal action in civil courts.”

[23] This is not an abstract consideration, for the latest (1979 and 1980) guidance on church courts specifies that “just prior to inviting the accused member into the court, the bishop should describe the case briefly to the court members and should explain what constitutes guilt under the charge and what are considered sufficient grounds for action by the court.” (Emphasis added.)

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue