Articles/Essays – Volume 13, No. 2

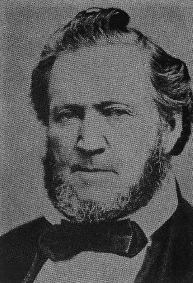

The Orson Pratt-Brigham Young Controversies: Conflict Within the Quorums, 1853 to 1868

Brigham Young and Orson Pratt are both regarded as valiant leaders during the first generation of the restored Church. Both worked mightily in the missionary field and showed themselves stalwart defenders of the faith. Yet there were differences between them. Those differences were not hidden to the Latter-day Saints of the past century; they were referred to in conference sermons and in statements and retractions in the Deseret News and Millennial Star. In retracing the fascinating course of theological differences Gary James Bergera reminds us that dedicated leaders could disagree on points of doctrine and that the capacity to submit to higher authority when larger interests of the Kingdom are involved is itself a mark of greatness. It is worth emphasizing, too, that the differences sometimes separating Brigham Young and Orson Pratt were never as great or as fundamental as their common bonds.

[N] early every difficulty that arises in the midst of the inhabitants of the earth, is through misunderstanding; and if a wrong in intent and design really exists, if the matter is canvassed over in the manner I have advised, the wrong-doer is generally willing to come to terms.

—Brigham Young[1]

Among the many perceptions shared by faithful adherents of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, few are as strongly inculcated or pervasive as that of harmony among church leaders. From their faith’s 1830 inception, Mormons have been commanded, “[B]e one; if ye are not one ye are not mine.”[2] Nowhere is this sentiment more keenly asserted than within the presiding quorums of the First Presidency and Twelve Apostles—collectively, a small, tightly-knit group of Mormonism’s elite. Former President and Historian Joseph Fielding Smith said, “There is no variance among the teachers in Israel concerning the principles of the gospel. We are united concerning these things. There is no division among the authorities, and there need be no divisions among the people, but unity, peace, brotherly love, kindness and fellowship one to another.”[3] In spite of such well intentioned reassurances, Mormonism’s own turbulent history suggests that even within these church councils interpersonal conflict occasionally flares up.

Specifically, the little known conflict between President Brigham Young and Apostle Orson Pratt extended throughout the web of Mormon interpersonal and ecclesiastical relationships.

II

Five years after their arrival in the West, Mormon leaders began a public relations move calculated to offset public outrage over their recent announcement of plural marriage. High-ranking church authorities were called to large cities in the West, the mid-West and the East to oversee publication of pro-Mormon newspapers. Their purpose, as specified by Brigham Young, was to provide non-Mormon readers with a more positive view of church activities in the Rocky Mountains, with special emphasis on plural marriage.

Apostle Orson Pratt was the first church official to receive such an ap pointment.[4] His call came at the close of the August 1852 special conference held in conjunction with the public announcement of polygamy, which Pratt himself had delivered at Young’s request. Pratt’s early assignment showed, in part, his high standing and esteem among church councils and members.[5]

Arriving at his field of labor, Washington, D.C., in early December, Pratt began immediate negotiations for the publication of his brainchild, The Seer—named in honor of the martyred Joseph Smith. When the first sixteen page issue appeared during the last week of December, Pratt reported to Young, “I have taken the Seer to seven different book Stores and periodical depots in this city, and left them for sale on commission, but I have not heard of even one copy being sold.

. . . I have had large hand bills about 2 feet square handsomely printed on good paper to be posted up in front of the book stores; many are so prejudiced that they would be ashamed to have such a bill before their door; while other booksellers, after reading the Seer refused to offer them for sale and requested me to take them away, and the people generally dare not enquire for a Mormon paper, because they are ashamed to do so.[6]

Much of the Washington-based book trade’s apprehension no doubt stemmed from Apostle Pratt’s characteristically bold presentation. His pros pectus left no room for question as to his intentions: “The views of the Saints in regard to the ancient Patriarchal Order of Matrimony, or Plurality of Wives, as developed in a Revelation, given through JOSEPH the SEER, will be fully published.” [Emphasis in original.][7] Ever true to his word, Pratt printed in the inaugural number Smith’s 1843 relevation on “celestial marriage,” appending to it an extended commentary by the Apostle himself.[8]

The effort of writing, editing and publishing the monthly journal was considerable. Since he had other responsibilities as the Church’s east coast representative, the weight of his calling was heavy indeed. “Every item,” Pratt wrote to Young, “yet admitted into the Seer has been new matter of my own composition. It is no small task to write 112 pages of printed matter as large as the Seer.[9] I am confident that I will have to rest my mind a little and exercise my body more in order to preserve my health.”[10] He left the United States that month for England, an earlier and much loved field of missionary labor, remaining until September. While there, the diligent Pratt took his sixth plural wife.

Following his return home to the nation’s capital, he wrote his older brother, Parley, expressing his own hopes and fears:

Writing has always been tedious to me, but seeing the good that may be accomplished, I have whipped my mind to it, till I am nearly bald-headed, and grey-bearded, through constant application.

I almost envy the hours as they steal away, I find myself so fast hastening to old age. A few short years, if we live, will find us among the ranks of the old men of the earth; and how can I bear to have it so without doing more in this great cause? .. . [Y]ou would no doubt counsel me to be patient, but I would remark, that I sometimes fear that while I am waiting with patience that the day of my probation will be past and that I may be called away before I have prevaled with God as did the ancients. I will try, my dear brother, to be patient, but sometimes my anxieties are so great that it is hard to wait. [Emphasis in original.][11]

In his role as defender of the faith, Pratt had few equals. In time, however, these very gifts would earn him not only distant respect but the fear of his own church president.

The first inkling he had of Young’s growing disapprobation came by mail in early November 1853. In a letter dated September 1, Young advised Pratt that certain points of doctrine treated in the pages of the Seer “are not Sound Doctrine, and will not be so received by the Saints.” [Emphasis in original.][12] This criticism was general, not specific. Pratt had received a letter from a close friend at church headquarters who, evidently privy to a less reserved Young, was able to alert Pratt to several of the President’s more pointed accusations. On November 4, Pratt hurriedly wrote President Young a six-page letter, to which he attached a short confession.

It appears that Brigham Young was at odds with the Apostle’s reasoning on a plurality of Gods, a doctrine publicly proclaimed by Joseph Smith two months before his violent death in June 1844.[13] Pratt had defined God as a quality or attribute rather than a corporeal being. He explained to Young,

[T]he Unity, Eternity, and Omnipresence of God, consisted in the oneness, eternity, and Omnipresence of the attributes, such as ‘the fulness of Truth,’ light, love, wisdom, & knowledge, dwelling in countless numbers of tabernacles in numberless worlds; and that the oneness of these attributes is what is called in both ancient & modern relevations, the One God besides whom there is non other God neither before Him neither shall there be any after Him. [Emphasis in original.]

Pratt had also written, “The Father and the Son do not progress in knowledge and wisdom, because they already know all things past, present, and to come.”[14]

Significantly, he saw his efforts as designed to reconcile teachings on the Godhead found in the Bible with those contained in Mormon canon. ” [With out these arguments I have not the most distant idea how to reconcile them,” he lamented to Young,

without these arguments I could not stand one moment before arguments brought by our opponents; without these arguments, it would be entirely vain for me to try & enlighten the world upon this subject by reason. I could only bear my testimony that there was but one God as clearly declared in our revelations, & that there were many Gods as asserted in the same revelations, and there I should have to leave it, as a stumbling block before the world and as a stumbling block before many that are honest, though uninformed.

Pratt’s sympathies were clearly with those who questioned contradictions, as they saw them, in Mormon dogma. It was his desire that church teachings be amenable to human understanding and reasoning rather than a “stum bling block.” In fact, the majority of his writings stressed the rationality of the Church. At the onset of The Seer’s publication, Pratt had challenged his

non-Mormon readers, “[C]onvince us of our errors of doctrine, if we have any, by reason, by logical arguments, or by the word of God, and we will be ever grateful for the information. . . “[15] His treatment of plural marriage, for instance, was founded on the premise of its existence among the prophets and leaders of ancient Israel.

Clearly, he thought Brigham Young should also be expected to meet standards of rationality and consistency. “[N] either can I persuade myself, even now,” he wrote, “that minds accustomed to severe thought and meditation as yours have been these many years, can, after due reflection, and reading the vast number of revelations which seem most clearly to teach differently, still believe in a doctrine which appears to be so contrary to what is revealed.”[16] He added, “It is not through self-will or stubbornness that I have published what I have upon this subject. I have published, whether right or wrong, what I verily and most sincerely believed to be the true doctrine revealed. . . .

I hope that you will grant me as an individual the privilege of believing my present views, and that you will not require me to teach others in the temple, or in any other place that which I cannot without more light believe in regard to the eternal progression of all Gods in knowledge. I do not ask any one else to believe as I do upon this subject. . . . [H]ad I been persuaded that you did in reality entertain permanent views contrary to what I have published, I should have kept my views away from the public, for it is not my perogative to teach publicly that which the president considers to be unsound.

Pratt enclosed a short, carefully worded confession to be published at Young’s discretion in the church-owned Deseret News. Though never printed, Pratt’s statement was no doubt greeted with relief. His disclaimer read, in part, “I do most earnestly hope that the Saints throughout the world will reject every unsound doctrine which they may discover in the ‘Seer’ or in any of my writings. Whatever may come in contact with the settled & permanent views of our president should be laid aside as emanations of erring human wisdom.” [Emphasis in original. ][17]

The stage, however, had been set for further confrontation. Pratt would submit to the demands of President Young, yet he would tenaciously retain the right to freedom of thought he felt to be beyond Young’s ecclesiastical mandate. In the absence of binding declaration, he saw as his privilege the right to arrive at knowledge and truth through any means available. Pratt’s reluctance to admit error would serve as the most significant cause of Young’s continued criticism.

Pratt’s conversion to Mormonism had come from independent thinking which led to a disaffection from traditional creeds. Similarly, Brigham Young’s acceptance of the new religion had come after a careful weighing of the claims of the infant church in terms of his own experience and understanding. Some two years had passed between his initial contact with Mormon missionaries and his baptism in 1832. As he later recalled, “I wished time sufficient to prove all things.”[18] Privy to private conversations of the hierarchy since his appointment to the quorum of the Twelve in 1835, Young knew well the consequences of extravagant doctrines. Both men realized that many of the Saints’ first attraction to the Church had been brought on by intellectual questioning. Yet each church authority viewed his basic value from subtly different perspectives. Young, as president, feared the potentially dangerous effects of Pratt’s logic, while Pratt appreciated the value of a reasoned faith. The difference, one of emphasis, would become increasingly polarized.

Pratt returned to the Great Salt Lake Valley to deliver his homecoming report to Church leaders on 3 September 1854. Two weeks later to the day, Young privately reproached the Apostle during a prayer meeting of ranking general authorities. He warned Pratt that his interpretation of the omniscience of God “was a fals doctrin & not true that thare never will be a time to all Eternity when all the God[s] of Eternity will seace advancing in power knowledge experience & Glory for if this was the case Eternity would seace to be & the glory of God would come to an End but all of celestial beings will continue to advance in knowledge & power worlds without end.” The President also took issue with Pratt’s acceptance of Adam’s having been created out of the dust of this earth. Young maintained that Adam “came from another world & brought Eve with him partook of the fruits of the Earth begat children & they ware Earthly & had mortal bodies & if we are faithful we should become Gods as [Adam] was.” Apostle Wilford Woodruff recorded that the President “told Brother Pratt to lay aside his Philosofical reasoning & get revelation from God to govern & Enlighten his mind more . . . [he] said his [Pratt’s] Phylosophy injured him in a measure. . . .”[19]

Pratt was not the only member unwilling to embrace certain of Young’s views. Yet his calling as Apostle placed him at the forefront of dissent. Follow ing a strong Adam-God statement delivered by Young during the October 1854 general conference, one member observed, “[T]here were some that did not believe the sayings of the Prophet Brigham. Even our beloved Brother Orson Pratt told me that he did not believe it. He said he could prove by the scriptures it was not correct. I felt sorry to hear Professor Orson Pratt say that. I fear lest he should apostatize.”[20] The day after these observations, Pratt addressed the faithful in the Old Tabernacle. Vaguely alluding to present difficulties, he cautioned those members gathered for the semi-annual conference:

So far as I have ever preached abroad in the world, and published, one thing is certain, I have not published anything but what I verily believe to be true, however much I may have been mistaken, and I have generally endeavored to show the people, from the written word of God, as well as reason, wherein it was true. This has been by general course . . .

. . . Previous to declaring a doctrine, I have always inquired in my own mind, “can this doctrine be proved by revelation given, or by reason, or can it not? If I found it, could be proved, I for the doctrine; but if I found there was no evidence to substantiate it, I laid it aside; in all this, however, I may have erred, for to err is human.”[21]

Eight days later, again facing Mormon faithful, he intimated that his error, if he had indeed committed one, had not been in writing or preaching doc trines out of harmony with those of the church president, for he had not previously learned of Young’s own views: “I do not know that I have this day presented any views that are different from his: if I have, when he corrects me, I will remain silent upon this subject, if I do not understand it as he does.”[22] His error, as he saw it, was not necessarily in espousing faulty beliefs, but in possibly expounding doctrines considered contrary to the opinions of the president—which conflict he was unaware of at the time.

Pratt could not help but realize, however, that at least one, perhaps two, of his teachings were not well received by Young. It may be that Pratt’s public comments were intended to be a not-so-subtle invitation purposely designed to incite Young’s equally public response. With their disagreements known by members other than those of the church’s top-level leadership, Pratt may have felt he would have stood a better chance at defending his beliefs.

One month later, the Deseret News announced the publication of Pratt’s edition of Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations, by Lucy Smith, Mother of the Prophet.[23] During his fall 1852 journey to Washington, D.C., Pratt had obtained a manuscript dictated by Joseph Smith’s mother relating past events of the Smiths’ lives. Pratt, quick to realize that printing costs in the United States would prohibit its American appearance, had the manuscript published in England during the summer of 1853 by church representative Samuel W. Richards. In his eagerness, he had not sought official approval, nor had his editing corrected several textual errors. Young had been told of Pratt’s intentions on 31 December 1852, though it is doubtful that Pratt thought official approval really necessary. Four months after the book’s appearance in Utah, Pratt informed readers of the Deseret News that Smith’s history did contain some inaccuracies; that Joseph Smith could not have reviewed it before his death—as Pratt had earlier assumed—and that all future editions “will be carefully revised and corrected.” Obviously Pratt thought the problems were minor and did not seriously detract from the book’s value. “If the schools of our Territory would introduce this work as a ‘Reader,’ he wrote, “it would give the young and rising generation some knowledge of the facts and incidents connected with the opening of the grand dispensation of the last days.”[24] As additional errors became apparent, however, Pratt’s failure to first secure church sanction resulted in strong condemnation from some leaders. “[T]he brethren would have made it a matter of fellowship,” Young explained five years later. “[I] did not have it in [my] heart to disfellowship but merely to correct men in their views.”[25]

During the latter part of 1854, and continuing into the early months of 1855, the Church’s English organ, The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, edited by Samuel Richards, had been reprinting several of Pratt’s writings from The Seer. By late January 1855, Brigham Young learned of them and asked Richards to discontinue republication of the controversial articles. Richards received Young’s letter in early May, and at the latter’s request, printed pertinent extracts. Though Pratt had earlier hinted that his writings may not have met Young’s unqualified approbation, Young’s 1855 letter marked the first public announcement of this disapproval. Taking note of The Seer’s “many items of erroneous doctrine,” the President wrote:

As it would be a lengthy and laborious operation to enter minutely into their disapproval, I prefer, for the present, to let the Saints have the opportunity to exercise their faith and discernment in discriminating between the true and erroneous; and simply request them, while reading the ‘Seer,’ to ask themselves what spirit they are of, and whether the Holy Ghost bears testimony to the truth of all the doctrines therein advocated.[26]

Throughout the intervening months, the discourses, both private and public, of Pratt and Young revealed that neither man had substantially altered his conflicting views. In Sunday morning services at the Old Tabernacle in early 1855, Pratt commented on the Mormon concept of opposition as connected to Adam and Eve in the Garden. He also announced “the plurality of Gods as written by [me] in the ‘Seer’ [was] for the benefit of Elders who might be abroad at any [time] preaching to the world.” During the afternoon session, Young, who had attended the morning services, arose and “spoke to the Meeting in a very interesting manner referring to several points touched upon in the morning by Bro. Pratt. Did not seem fully to fancy Orson’s idea bout the ‘Great Almighty God’ refering so especially to his attributes.”[27] Less than two months later, Young, in Pratt’s presence, explained his super-scriptural vision of the creation of this earth. Adam and Eve, Young held, arrived upon this world having previously earned their exaltation upon another. Their eternal reward consisted in peopling this earth, “redeeming [Adam’s] posterity & exhalt[ing] them to all the glory they were capable of receiving.”[28] Young’s interpretation contradicted Pratt’s belief in man’s physical creation from the dust of this earth, his subordinate position in relation to Deity and the eventual acquisition of all knowledge by those who attained ultimate exaltation.

On 17 February 1856, during a council meeting of the Twelve, Young pointedly asked Pratt’s opinion, of his belief that “intelligent beings would continue to learn to all Eternity.” The outspoken Apostle, with customary frankness, responded that “he believed the Gods had a knowledge at the present time of evry thing that ever did exist to the endless ages of all Eter nity. He believed it as much as any truth that he had ever learned in or out of this Church.” Young retorted that “he had never learned that principle in the Church for it was not taught in the Church for it was not true it was fals doctrin For the God[s] & all intelligent beings would never sease to learn except it was the Sons of Perdition they would continue to decrease untill they became dissolved back into their native Element & lost their Identity.”[29]

Three weeks later, both men again locked horns. Samuel Richards recorded,

A very serious conversation took place between Prest. B. Young and Orson Pratt upon doctrine. O. P. was directly opposed to the Prest views and freely expressed his entire disbelief m them after being told by the President that things were so and so in the name of the Lord. He was firm in the Position that the Prest’s word in the name of the Lord, was not the word of the Lord to him. The Prest did not believe that Orson would ever be Adam, to learn by experience the facts discussed, but every other person in the room woula if they lived faithful. [Emphasis in original.[30]

Elder Woodruff, present during this clash, added, “Elder Orson Pratt pur sued a course of stubborness & unbelief in what President Young said that will destroy him if he does not repent & turn away from his evil way For when any man crosses the track of a leader in Israel & tryes to lead the prophet—he is no longer lead by him but in danger of falling.”[31]

Yet Brigham Young recognized Pratt’s leadership abilities. It seems doubt ful that the Apostle’s numerous missionary assignments were motivated only by Young’s unwillingness to tolerate such dissent among Utah Mormons. In April 1856, Pratt departed the Valley for England where he had twice earlier assisted in the founding and organization of the church’s European mission. He arrived in Liverpool in mid-July to begin his tenure as mission president. Shortly thereafter, inflamed by the fires of Mormonism’s then-in-progress Reformation, Pratt published a small pamphlet on the “Holy Spirit,” rewritten in part from a work he had first issued in 1850.[32] Despite reassurances to Young that he would avoid discussion of such topics, Pratt again outlined his concept of God and associated attributes, adding an additional commentary on the nature of the Holy Spirit. Pratt conceived this spirit “as a boundless ocean,” possessing “in every part, however minute, a will, a self-moving power, knowledge, wisdom, love, goodness, holiness, justice, mercy, and every intellectual and moral attribute possessed by the Father and the Son.”[33] Through this omnipresent spirit a fullness of godly attributes was to be ob tained. Indeed, for Pratt the spiritual tabernacles of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, if organized at all, were the result of the many varied combi nations and unions of the particles of this indescribable spirit matter. Implicit in this view was the possibility Young found so distasteful: The Holy Spirit existed for and enlightened to some extent the Sons of Perdition.

When the work reached Utah, President Young’s criticisms were prompt and unequivocal. Young first made mention of Pratt, still abroad, during a private meeting in his office on 29 December 1856. Wilford Woodruff reported that the President said “if he [Pratt] did not take a different course in his Phylosophy & [illegible] he would not stay long in the Church.”[34] Young’s personal reservations were rapidly becoming public knowledge. Less than two months later, he openly decried “our brother philosopher Orson Pratt”:

With all the knowledge and wisdom that are combined in the person of brother Orson Pratt, still he does not yet know enough to keep his foot out of it, but drowns himself in his own philosophy, every time he undertakes to treat upon principles that he does not understand. . . . [H]e is dabbling with things that he does not understand; his vain philosophy is no criterion or guide for the Saints in doctrine.[35]

Admittedly dramatic, perhaps purposely so, Young’s public position, unlike past ambiguities, left no room for question in the minds of Mormons: Apostle Pratt’s teachings were not to be relied upon by members as statements of binding (or even accurate) church doctrine.

Not surprisingly, Pratt felt Young’s blanket denunciation unjust, his criticisms too general, condemning as they did virtually all of Pratt’s writings. On 24 March 1858, two months after his arrival home, Pratt brought formal complaint against his President before the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. Apostle Woodruff, who presented Pratt’s complaints, explained that Pratt did not believe in some of the teachings of President Young and thought Young had reproved him unjustly. The subject was discussed at length by the Twelve and President Young, much instruction was given at the close Orson Pratt confessed his faults and said that he would never teach those principles again or speak them to any person on the earth we all forgave him and voted to receive him into full fellowship.[36]

What had begun as an official inquest initiated by Pratt himself resulted in near disfellowshipment for the outspoken Apostle.

For nearly two years Pratt’s public discourses were remarkably free of speculations. However, on Sunday, 11 December 1859, he again proclaimed his notions of the Godhead to church members gathered in the Tabernacle for weekly religious services, explaining that “it was the attributes of God that he worshiped and not the person & that he worshiped those attributes whether he found them in God Jesus Christ Adam Moses the Apostles Joseph Brigham or in anybody Else.”[37]

It may never be fully known why Orson Pratt undertook public espousal of a topic he knew to be inviting official reprimand. He may have consciously attempted to initiate a formal response to his doctrinal writings. If so, his calculations proved unquestionably successful, for they precipitated two official statements of censure.

III

Orson Pratt’s December sermon prompted several general authorities to suggest that they meet to discuss the apostle’s continued excesses.[38] Within less than two months, Young called to order in his Council Room a high level meeting of Church leaders on Friday, 27 January 1860, at 6:00 P.M. This august group included members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Presidents of the Seventy, the Presiding Bishop, church secretaries and lesser authorities.

At the onset, Young announced, “[T]he object of the Meeting [is] to convers upon Doctrinal Points to see if we see alike & think alike. I Pray that we may have the spirit of God to rest upon us that our minds may be upon the subject & that we may speak by the Holy Ghost.”[39]

The President asked Apostle Albert Carrington to read the press copy of Pratt’s recent discourse. Young had seen to it that of those present, only Carrington, Pratt and Young himself had been informed of its authorship. Yet it is doubtful that the majority present were unaware of Pratt’s guilt. When Young asked those who supported Pratt’s views on “attributes” to manifest it by saying “Yes,” the room was silent. He then announced,

This is O Pratts sermon prepared for the Press. I do not want it published if it is not right. Brother Orson worships the attributes of God but not God I worship not the attributes but that God who hold and dispenses [them] if Eternity was full of attributes and not one to dispense them they would not be worth a feather . . . Joseph [Smith] said to us I am a God to this people & so is any man who is appointed to lead Israel or the Kingdom of God if the people reject him they reject the one who sent him but we will let that drop, and turn to the other subject now.

“[S]uppose,” he postulated, “we were all to receive a fulness of the attributes of God and according to Orson Pratts theory the Lord had a fulness and he could not advance but we could advance till we were equal to him then if we worshiped the attributes instead of God we would soon worship our selves.

. . . [Y]ou would then worship the attributes & not the dispenser of those attributes ‘this is fals doctrine’ God did not say worship Moses because he was a God to the people, you may say to your wife or son do so & so. they will say I will not out I will go to a greater man I will go to Brigham Young, you might say I am your councillor Dictator or you[r] God. Either would be correct and they should obey your Just & righteous Command yet they should not worship you for this would be sin. Orson Pratt has differed from me in many things. But this is a great principle & I do not wish to say you shall do so & so I do not know of a man who has a mathematical turn of mind but what goes to[o] Far The trouble between Orson Pratt & me is I do not know enough & he knows too much. I do not know everything There is a mystery concerning the God I worship which mystery will be removed when I come to a full knowledge of God . . . Wnen I me[e]t the God I worship I expect to [meet] a personage with whom I have been acquainted upon the same principle that I would to meet my Earthly Father after going upon a Journey & returning home.

Several apostles voiced their support of Young’s remarks. Some added similar views. Apostle Woodruff, in comments seconded by others, re marked,

[I]t is our privalege so to live as to have the spirit of God to bear record of the Truth of any revelation that comes from God through the mouth of his Prophet who leads his people and it has ever been a key with me that when the Prophet who leads presents a doctrine of principle or says thus saith the Lord I make it a policy to receive it even if it comes incontact with my tradition or views being well satisfied that the Lord would reveal the truth unto his Prophet whom he has called to lead his Church before he would unto me, and the word of the Lord through the prophet is the End of the Law unto me.

Throughout the evening’s lengthy meeting, Pratt had remained remarkably subdued. Though the solitude of his position weighed heavily upon him, his convictions were solidly founded. He finally mentioned his desire to speak.

I have not spoken but once in the Tabernacle since conference I then spoke upon the revelations in the Doctrine & Covenants concerning the Father & son & their attributes . . . I sincerely believed what I preached, how long I have believed this doctrin I do not know but it has been for years I have published it in the Seer. I spoke of a plurality of Gods, in order to worship God I said that I adored the attributes wherever I found them I was honest in this matter. I would not worship a god or Tabernacle that did not possess Attributes if I did I should worship Idols . . . Now the reason I worship the Father is because in him is combined the attributes if he had not those attributes I would not worship him any more than I would this chair. I cannot see any difference between myself and Prest. Young. . . . I must have something more than a declaration of President Young to convince me I must have evidence.

I am willing to take President Young as a guide in most things but not in all. President Young does not propose to have revelations in all things. I am not to loose in my agency I nave said many things which President Young says is False I do not know how it is I count President Young equal to Joseph and Joseph equal to President Young. . . . When Joseph teachs any thing & Brigham seems to teach another contrary to Joseph .. . I believe them as Joseph has spoken them .. . I have spoken plainly I would rather not have spoken so plainly but I have no excuses to make President Young said I ought to make a confession But Orson Pratt is not a man to make a confession of what I do not believe. I am not going to crawl to Brigham and act the Hypocrite and confess what I do not Believe. I will be a free man President Young condemns my doctrines to be fals I do not believe them to be fals which I published in the Seer in England. .. . I will not act the Hypocrite it may cost me my fellowship But I will stick to it if I die tonight I would say O Lord God Almignt[y] I believe what I say.

Pratt’s dramatic declaration caught most by surprise. Young said, “Orson Pratt has started out upon false premises to argue upon his founda tion has been a false one all the time and I will prove it false. “You have been like a mad stubborn mule,” he turned to Pratt,

and have taken a fals position in order to accuse me you have accused me of worshiping a stalk or stone or a dead body without life or attributes you never herd such a doctrin taught by me or any leader of the Churcn it is fals as Hell and you will not hear the last of it soon. You know it is false Do we worship those attributes No we worship God because he has all those Attributes and is the dispenser of them and because he is our Father & our God. Orson Pratt puts down a lie to argue upon he has had fals ground all the time tonight . . .

Again, those authorities in attendance sided with their President. Apostle Hyde said to Pratt, “My opinion is not worth as much to me as my fellowship in this Church.” Others added their words of harsh rebuke. Pratt, according to the official minutes, offered no further defense. Before the close of the six-hour meeting, Young remarked,

I will tell you how I get along with Joseph. I found out that God called Joseph to be a Prophet I did not do it. I then said I will leave the Prophet in the hands of that God who called and ordained him to be a Prophet. He is not responsible to me and it is none of my business what he does. It is for me to follow & obey him. .. . I told Brother Joseph he had given us revelation enough to last us 20 years when that time is out I can give as good revelation as their is in the Doctrine & Covenants.

. . . [N]o man can live his religion without living in revelation but I would never tell a revelation to the Church unless Joseph told it first. Joseph once told me to go to his own house to attend a meeting with him he said that he should not go without me. I went and Hiram Preached upon the Bible Book of Mormon & Doctrine & Covenants and says we must take them as our guide alone he preached very lengthy until he nearly wearied the people out when he closed Joseph told me to get up. I did so I said that I would not give the ashes of a rye straw for all those books for my salvation without the living oracles. I should follow and obey the living oracles for my salvation instead of anything else when I got through Hyrum got up and made a confession for not understanding the living oracles.

“It may be thought strange by the Brethren,” he added, “that I will still fellowship Elder Pratt after what he has said but I shall do it, I am determined to whip Brother Pratt into it and make him work in the harness.”

Though the veteran Apostle had no doubt anticipated, perhaps even initiated the tense meeting, it may have come as personally unsettling that he had stood against his President. Intelligent, courageous, unyielding and now very much alone, Pratt painfully began to realize the gravity of the situation in which he found himself—not only in relation to his quorum, but with increasing importance to his church.

The following day, Pratt called early upon Young at the latter’s office. The bearded Apostle readily admitted “he was excited, and for the future would omit such points of doctrine in his discourses that related to the Plurality of Gods, &c. but would confine himself to the first principles of the Gospel.” He asked if Young could not find a vacancy for “his son Orson” as a clerk. To his surprise, the President replied that he would attempt to appoint Apostle Pratt as a teacher, “as [Young] meant to promote education as much as possible.”

Young again remarked that “much false doctrine arose out of arguing upon false premises, such as supposing something that does not exist, as a God without his attributes, as they cannot exist apart.” Pratt replied, as he had also on past occasions, that “many of his doctrinal arguments had been advanced while in England in answer to the numerous enquiries that were made of him by reasoning men.” Young was not sympathetic, and added, “[W]hen questions have been put to me, by opposers, who did not want to hear the simple Gospel message [I] would not answer them.” Young asked Pratt “why he was not as careful to observe the revelations given to preach in plainness and simplicity as to so strenuously observe the doctrines in other revelations.”[40] Existing records give no mention of Pratt’s response, if, indeed, one was made.

As leading General Authorities and faithful church members met in Sun day morning services at the Old Tabernacle the next day, only one man present—other than Pratt himself—was aware of the potentially momentous discourse to be delivered from the podium.[41] Pratt had earlier discussed with fellow Apostle, Ezra T. Benson, the propriety of publicly commenting on Friday evening’s meeting. Wilford Woodruff, one of many Saints in at tendance, recorded his own amazement and relief at Pratt’s apparent confession:

Orson Pratt was in the stand and Quite unexpected to his Brethren he arose before his Brethren and made a very humble full confession before the whole assembly for his opposition to President Young and his Brethren .. . I never herd Orson Pratt speak better or more to the satisfaction of the People, then on this occasion, he would not partake of the sacrament untill he had made a confession then he partook of it.[42]

In the course of his continuing confession, Pratt made direct reference to his recent encounter with church leadership. As he gained the pulpit he asked his audience, “Where are there two men in the world who see eye to eye?— that are of the same mind? They can scarcely be found. I doubt whether they can be found in the world. Within a world dominated by disunity and confusion stands before all men and women a standard: the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The authority of Jesus Christ sent down from heaven, conferred upon man by His Holy Angels, or by those that may have previously received divine authority, is the true and only standard here upon the face of our earth; and to this standard all people, nations, and tongues must come, or be eventually taken from the earth; for this is the only authority which is everlasting and eternal; and which will endure in time ana throughout all eternity.

“There are some points of doctrine,” he said, “which I have unfortunately, without knowing beforehand what the views of the First President of this church of God were, thrown out before the people.” Echoing earlier apologies, he maintained that initially he “did most sincerely believe that they were in accordance with the word of God.” Only later was he to learn from “the mouth of our President Brigham from the mouth of that person whom God has placed at the head of this church, that some of the doctrines I had advanced in the ‘Seer’ at Washington were incorrect. It was my duty as a servant of God to have at once yielded my judgement to his judgement,” he admitted. “But I did not do it.”

I did not readily yield. I believed at the time that he was as sincere in his views and thoughts as I was in mine; and thought that I had made up my mind upon the word of God in relation to the matter, and concluded that it was not my duty to yield my judgement to him. . . . The consequence has been, I have oftentimes felt to mourn, have been sorrowful in my own mind in relation to this matter . . .

When I say, I am going to repent of these things, I mean that I am going from this time henceforth, through the grace of God assisting me, to try and show by my acts and by my words, that I will uphold and support those whom God has placed over me to govern, direct and guide me in the things of this kingdom.

I do not know that I shall be able to carry out those views; but these are my present determinations. I may have grace and strength to perform this’ and perhaps I may henceforth be overcome, I feel exceedingly weak in regard to these matters.

The errant Apostle briefly mentioned other areas of disagreement between the president and himself. In every instance, however, whether those in volved be apostles or rank-and-file church members, Pratt said, when one’s personal beliefs or opinions come in conflict with those of the church presi dent, one must yield to his more authoritative judgment:

If the Prophet of the living God, who is my standard, lays down a principle, whether it be a principle of doctrine, or a principle in philosophy, or a principle in science, or a principle pertaining to anything whatever, it is not for you nor me to argue against it, and set up our standard, and our views, and our judgement in order to make a division goes no further than our own individual selves. We must bow, if we would bring about the oneness spoken of in the revelations of God. We must yield to those things; and it is my determination to do so.

And if a prophet “should lay down a principle in philosophy which to all human appearance appears to be perfectly incorrect?” Then, Pratt replied, “I would say I am weak . . . If I cannot fully understand his views, it is my duty at least to be silent in regard to my own.”

“These, ” the Apostle concluded, “are my feelings to br. Brigham. I will make reconciliation to him .. . in so far as I have been stubborn and not yielded to the man God has ordained to lead me. I consider these to be true principles, however imperfect. I may have been; it has nothing to do with the principles; the principles are from heaven, let br. Pratt do as he will: Amen.”

Relief no doubt engulfed the forty-eight-year-old general authority as he regained his seat. He had openly acknowledged his error in publicly espousing beliefs and doctrines regarded as incorrect by his President; reaffirmed his own conviction in the necessity of aligning one’s thoughts and actions with those of God’s appointed servants; and committed himself to refrain from further public speculation, though expressing his deep-felt concern at his ability to do so. His confession and repentance genuine, Orson Pratt probably settled back a little more comfortably into his chair.

Two days after his confessional sermon, Pratt called again upon Young at the president’s office and there “made a personal acknowledge to the President admitting he had a self willed determination in him.” Young consoled him: “he had never differed with him only on points of doctrine, and he never had had any personal feelings, but he was anxious that correct doctrines should be taught for the benefit of the Church and the Nations of the Earth.” The President also remarked that Pratt “had been willing to go on a mission to any place at the drop of the Hat and observed you might as well question my authority to send you on a mission as to dispute my views in doctrine.” Pratt responded, though indirectly, that “he had never felt unwillingness in the discharge of his practical duties.”[43]

Despite Young’s apparent congeniality, the Apostle’s Sunday discourse had not solved the problem. Before the close of the week, Young, aided by his second counselor, Daniel H. Wells, was examining extracts from Pratt’s Seer writings.[44] Saddened and angered, Young related to Wells that “there were many principles that the world were unworthy to receive; for they would only trample on it.” The President confessed, “If [I] had ever erred it was in giving too much revelation; instead of not giving enough. The Lord designed keeping those in ignorance who would not Seek unto him; and would impart knowledge to those who Kept his commandments.”[45]

Twelve days later, Elder Ezra T. Benson, at Young’s request, visited with the President in his office where he “had some conversation with the Prest about Orson Pratt’s discourse, on the subject of attributes.”[46] Later, on March 4, Young, together with First Counselor Kimball and Apostles Woodruff, Taylor, and Lorenzo Snow, met with Counselor Wells, convalescing from a recent illness, at his home. During their visit, Young again affirmed,

I did not say to [Pratt] that God would increase to all Eternity. But I said that the moment that we say that God knows all things Comprehends all things and has a fulness of all that He ever will obtain that moment Eternity ceases you put bounds to Eternity & space & matter and you make an end and stoping place to it. . . . No man can understand the things of Eternity And Brother Pratt and all men should let the matter of the gods alone I do not understand these things Neither does any man in the flesh and we should let them alone.[47]

What had been for Pratt a sincere, painful declaration of personal repentance was proving to be but one additional source of conflict.

In keeping with established procedure, Pratt’s January sermon had been scheduled to run verbatim in the Deseret News, Wednesday’s edition, February 22. Mention of it had previously appeared in a brief, front-page blurb in the February 1 issue of that Mormon newspaper. The day before its complete printing, however, a dissatisfied Young ordered the discourse removed from the front page and an insertion explaining its absence put in its place.[48] Ironically, the closing comments of Pratt’s lengthy sermon, which had been pasted-up to run on the second page, were printed before the oversight was detected. The editor of the News obliquely said, “Through some inadvertency, part of a sermon that had not been intended for publication in this number got inserted on the second page and that side of the paper was struck off before the mistake was discovered.”[49] Aside from this notice, however, no other mention was made of the deletion. When Wednesday’s edition appeared, it contained only the ending of Pratt’s confession.

Brigham Young had purposely delayed formal action on Pratt’s discourse until April 4, when a majority of apostles would be assembled in Salt Lake City for church general conference. Unlike January’s meeting, this was attended by only a select few of the church’s authorities. United again, with Young presiding, were Apostles Hyde, Taylor, Woodruff, Benson, Presiding Bishop Edward Hunter and Elder George A. Smith, who alone had not been present at the January 27 meeting. They were belatedly joined by Elders Erastus Snow and Charles C. Rich.[50]

As those present began to take their seats, Young turned to Pratt and asked, “Bro. O. Pratt, has Bro Benson spoken to you about that for which we have met to night?” The Apostle responded quickly and emphatically, “No!” “Well it is this bro. Orson,” Young returned, echoing an earlier scene:

Your late sermon had like to get into the paper, I want to get an understanding of your views, and see if we see things aright perhaps if I could see it as you Orson does perhaps its all that I could ask, but if not we want to have the matter talked over and laid before the Conference in a manner that we all see eye to eye . . . I presume bro. Pratt you have no objections to our taking this course and naving it all laid before the Conference satisfactorily.

Young asked Secretary Thomas Bullock to read Pratt’s confessional ser mon from Deseret News galley proofs. As Bullock finished, Young faced those members of the Twelve present. “Are the 12 satisfied with this & [with] what Bro. Pratt has put forth to the People? I do not want to do anything but what will be for the best and promote the public good.”

Orson Hyde responded first. “I thought when the prophet pronounced upon favorite doctrines, it was for us to repudiate ours, and sustain his. .. . As to whether we should sustain the prophet in every scientifical subject contrary to our judgement, it might not be policy to say that for invoking a principle of absolutism which would not look well.”

Elder Snow, who had missed the bulk of Young’s opening comments (as well as the Pratt speech itself) followed suit. He launched into a rambling statement of support for the Lord’s anointed, prophets whom he understood to be “kind fathers, not. . . tyrants & oppressors.” Young, perhaps sensing a drawn-out sermon, interrupted. “Erastus, a few words, be short, the evening will be spent.” Snow hurriedly finished his thought and Young began his rehearsed criticism. “The sermon is splendid,” he said, “but no confession of his errors, but a confession to me. As though a confession was to be made to me or I will take off Orson’s . . . head.” He reached for a copy of the dis course. “I wish to correct this,” he mentioned, “with items preached by Orson in the Seer. . . .

Orson wants a revelation to know that I am wrong No matter whether the men are right or wrong who lead the church. This is not the retraction that the statements made by Orson demands . . . I’m willing to go into the endowment house & dress before an [y] Quorum or as we are now, & or before Conference & lay down item upon item & let them decide you made attributes Deity [you might] as well say no deity now, or that we have to be dispersed to receive those attributes [and] go back to atoms before we get an exaltation. . . . It’s a confused mess & I want to wipe it carefully out & hurt nobody.

Young gestured to Pratt, “Bro. Orson’s honest integrity I know, I dont doubt them, I never did. When going to England first, he said Pie was] incapable of taking hold of a paper, he could not treat on new doctrine, he has gone a head of all the seers & prophets have written & deleanated upon.

“Im either of giving to have the quarelle there or having it go through in a parental spirit,” he said, exasperated.

I want to save bro Orson. I feel calm like an old shoe. If his confession had been right, I would [have] bound up my particle so that it would not have hurt his influence. [M]aybe tho he dont think I have revelations], if I dont I dont magnify my calling There are hundreds of thes I could write revelations as fast as dog[s] trot. When I write & send forth my Revelations [they] are then .. . as the Rev[elations] of eternity] I never look at my sermons, I dont cross my tracks. .. .

Turning to face President of the Quorum of the Twelve, Orson Hyde, Young demanded, “I want a confession that I can send to the whole of the people that will cover the church & preserve bro. Orson a whole Apostle, before the whole church, then we want bro Orson that can save him I want such a thing published all over the world. . . . Thus saith the Lord, ‘[G]o do that.’ Now you understand what I want, . . . If s not the matter Bro. Orson has at heart its the manner . . . Bro. Orson Pratt should say I have no judge ment upon the matter, or should have had none. Brother O. Pratt what do you think about it?”

Pratt could see but one response. “I have no doubt but what the first presidency] & Twelve can get up such a thing that would suit them, I have tried very hard to bring my feelings & judgement with Bro. Y[oung]s & that for several years. P]ts my duty to get my judgement I can feel that when a man’s made up he may have strong faith in regard to views that he considers to be true Revelation.

“There are certain points,” he said, “taught by Bro. Y as being true that there does seem to be disputed between those & the Revel [ations]

& when I reflect that there is—item upon item, doctrine upon doctrine—I would be a hypocrite if I came out & said that these [are] views on which I have strong faith [I] would be acting too much a hypocrite .. . I would like to ennummerate [those] items, first preached & publish [ed] that Adam is the fa [ther] of our spirits, & father of Spirit & father of our bodies. When I read the Rev [elations] given to Joseph I read directly the opposite.

“Your statements to night,” Young retorted, “you came out to night and place them as charges, & have as many against me as I have [against] you. One thing I have thought I might still have omitted,” he said. “It was Joseph’s doctrine that Adam was God when in Luke Johnson’s. . . .[51] Joseph could not reveal what was revealed to him, if Joseph had it revealed, he was told not to reveal it. .. . [There] is not a contradictory thing in what I have said. .. . If I have said anything that the people were not worthy of,” he confessed, “I have prayed that it might be forgotten.

I have prayed fervently when Orson published the sealing ordinance that it might be forgotten. Orson, it is for you to call the 12 together & do as I have suggested or do as you please. It will [then] be Drought before conference and you will be voted as a false teacher, & your false doctrines discarded. I love your integrity, but your ignorance is as great as any philosophers ought to be.

In the face of Young’s ultimatum, Pratt’s response was deliberate. “I am willing you should publish what you have a mind to. I cannot retract from what I have said. I sometimes feel unworthy of the apostleship which I hold.”

As he finished, a flurry of comments exploded. “These are temptations of Satan.” “It is a trick of the Devil to ruin a man, when it is suggested to him that those who are trying to put him right, are trying to put him down.” Pratt merely responded, “I am willing the twelve should publish all they consider necessary for the salvation of the church.”

At this perceived defiance, Elder George A. Smith took the initiative and moved that Pratt’s controversial doctrines be formally presented before church membership two days later in conference. Most present, however, did not share Smith’s views and instead voted to have the matter brought up again the following day before the Twelve. At their action, Young “wished the Twelve to take hold & pray with Bro. Orson & have a good flow of the Spirit, & it will go off smooth.” The less emotional President added, “Bro Pratt counts too little on his standing & calling too little, or he would not let his private judgement, stand between him & his salvation, or he would yield. But I attribute it to his ignorance.”

While offering no additional insights into the fundamental areas of Young’s and Pratt’s conflict, except, perhaps, to highlight the issue of Adam-God more clearly, the 4 April 1860 meeting did serve to further alienate Pratt from his brethren. Young clearly saw his duty as preventing the freedom of thought Pratt demanded. Young could hardly disagree with the Apostle’s firm insistence upon revelation as the ultimate determiner of truth. Yet Pratt’s tenacious belief that only personal revelation to himself would provide the impetus necessary to publicly proclaim his error was greeted by Brigham Young with understandable frustration. Young was not the revelator Joseph Smith had been; nor did he lay claim in any significant way to the kind of theological innovations Smith had earlier imparted to his followers. Young did not share Pratt’s view that direct divine intervention was indispensible in the formulation of doctrine. Pratt’s repeated references in his January 29 discourse to Young as God’s appointed representative on the earth strongly implied, as Young had sensed, that the President did not necessarily repre sent the views of the general membership of the Church. Though no doubt genuinely sincere in his declaration of personal subjection to his Prophet, Pratt, in the apparent excitement of the moment, exaggerated the extent to which such subjugation was binding upon members. In the same breath, however, he contradictorily implied that he would continue to think as he saw fit, attributing this to his weakness. Correct in his explanation that church leaders were not infallible, Pratt essentially offset the impact of his logic by illustrating his point with only the most extreme of possibilities. Not surpris ingly, Young felt threatened as President and insulted as an individual. No compromise was possible; the time had long since passed; and Young, for the sake of church unity and his own self-esteem, saw no other possibility but to demand that Pratt recant, preferably before the Twelve, and publicly announce his error. Otherwise, the dangerous Apostle would be presented to the conference faithful as a false teacher and sustained as such.

The much-traveled Pratt had successfully withstood a seemingly endless barrage of intellectual attacks on his religion during his earlier missions to England and the eastern seaboard of the United States. His keen reasoning had served him well, and he could not, in good conscience, abandon it now. For Pratt, freedom of thought was apparently of greater value and ultimate worth than was his church fellowship. Because the Apostle also idolized the martryred Joseph Smith, he could not admit to himself or to anyone else that any revelations, written or oral, received through Smith might be outmoded. His ties to the first Prophet were strong and complex. He saw himself, not as expounding new doctrine, but rather as adding to the collection already established.

When Young had first announced points of doctrine with which Pratt could not agree, or which contradicted Smith’s earlier teachings, the Apostle kept his silence, anticipating that supporting revelations would be forthcoming. No such revelations had been advanced, however, and Pratt was to perceive his views as valid as those of Young or any other member of the Twelve. Pratt’s allegiance was to the truth as he saw it, and as he believed Joseph Smith had revealed it—not to any one man or organization. Young’s continual insistence that Pratt acknowledge his faulty doctrine merely served to convince Pratt of the fundamental truthfulness of his position. In honesty not only to himself, but more to his beliefs, Pratt could not admit error where he saw none, even if it meant severence from his church.

At the new day’s meeting, Brigham Young was conspicuously absent. Elders Hyde, Pratt, Taylor, Woodruff, Smith, Rich and Richards arrived at the church historian’s office early. As they were reaching their seats, Pratt said, “I have come here by Bro. Taylor’s request, and if there are any objections I will withdraw.”[52]

“We want you here,” Elder Hyde replied. “[W]e dont want you to with draw, we have been together so long in Mormonism, that we are spoiled by anything else, it is too late to talk of casting out, or separating.”

Following the opening prayer, Hyde immediately confessed, “I do not feel competent to take up the points of difficulties in doctrine between bro. Pratt, & bro. Young. . . . [But] to acknowledge that this is the Kingdom of God, and that there is a presiding power, and to admit that he can advance incorrect doctrine, is to lay the ax at the foot of the tree. Will He suffer His mouthpiece to go into error? No. He would remove him, and place another there. . . .

“[B]ro. Brigham,”—he said, turning to face Pratt—”is responsible for the doctrine taught in this Church, and if he did not watch us, and reprove us when wrong, he would not do his duty,

and again if any of the Twelve was abroad, and any Elder was propogating a false doctrine, we dealt with that man, then why could we not be dealt with in the same manner? Shall he mourn and we not respond? It is a duty we owe to ourselves; he is the presiding authority of God on the earth, then he is legitimate, and every thing opposed to him, is not legitimate, bro. Pratt said he was discouraged and felt reckless, he ought not to be so! God is a jealous God, and His servants are jealous with a godly jealousy, that tne stream may roll in purity.

Elder Woodruff spoke next. “[T]he remarks of bro. Hyde are dictated by the spirit of wisdom, and the spirit of the Lord. [O]ur position, is very responsible, and we could not aspire to anything greater, having received the Apostleship, we should try to honor it;

when bro. Pratt made his confession, it made me rejoice, because I thought it was the first time that he felt to fall into the Channel, I would not do any thing to lose my Apostleship, I would rather lose my hand, or my life, I think bro. Pratt has gone too far in advancing the doctrine of the Godhead, they come in contact with the presidency of the Church. .. . I feel to thank the Lord for giving us as good a leader as bro. Brigham. no man had a right to call into question what Joseph did. He was led by the spirit of God. bro. Brigham is careful, cautious, and wise, and is a Father, his feeling is to save the people, every thing is Godlike and is filled with wisdom, I want to have bro. Pratt saved, to be one with the Presidency and his brethren.

Facing the errant Apostle, Woodruff commented, “[I]f bro. Pratt has taught a false doctrine, it is no worse for him, than me, or bro. Hyde, and should retract, when a man takes a stubborn course, all Israel feels it; I desire that he may right that matter up. The moment we launch out into unrevealed doctrine, we are liable to get into error, bro. Pratt ought to make the thing right with Pres. Young. … ”

“[T]he Majority of the Church feels that some of his writings are open to serious objections,” said Erastus Snow “.. . I have read some sweeping declarations in his writings, and thought some of them were dipping into deep water. He can qualify those words, so as to wipe them out. … ”

“[I]t has been sorrow to me that there has [been] any difficulty arisen between bro. Brigham and bro. Pratt,” Elder Charles C. Rich said. “I feel very anxious on this subject.

it is simply for bro. Pratt to remove the objectionable items, the brethren rejoiced at his confession, and it was an increase to his influence, it is not right for a member to have a doctrine opposed to his quorum, or the Presidency, he can cure the evil that is wanted to be cured, I would not want to yield the good that I can do, for any light thing, I would be glad to see bro. Pratt make it right. . . .

“[F]or one member to advocate new doctrine without common consent,” reminded Apostle Hyde then, “is beyond our pale or jurisdiction.”

“I do not see how I can mend the matter, one way or the other,” Orson Pratt began. “I think the brethren are laboring under a wrong impression,

in all my writings on doctrine, I have tried to confine myself within revelation .. . in regard to Adam being our Father and our God, I have not published it, altho I frankly say, 1 have no confidence in it, altho advanced by bro. Kimball in the stand, and afterwards approved by bro. Brigham[53] . . . I have never intended to advance new ideas, but to keep within revelation. It is said the revelations given to Joseph Smith, answered them, and if Joseph would translate now, it would be so very different, if that was so, I should never know when I was right, in fourteen years hence, all the revelation of Brigham may be done away, but I do not admit it, The Lord deals with us on consistent principles, there may be apparent contradictions, but to suppose that the meaning would be different, I do not believe [it]. . . .

For me to publish to the world, that the writings that I have sent out to the world, oacked up by Joseph’s revelations, are untrue, would be to say, how do we know that in sixteen years time, all these revelations will be overturned, as Joseph’s now are, they are written plain. I was willing that things should slumber. I made a confession as far as my conscience would allow me, to be justified. I could not state it from knowledge. I suppose it was all right, until I heard bro. Brigham declarations from the stand; that threw a damper on my mind, I will leave the event in the hands of my brethren . . .

“I really believed in regard to the omnipresence of the Spirit,” he pleaded, “I did really believe that bro. Brigham had preached the same doctrine. I have not tried to introduce new doctrines into the church, bro. Young’s sermon was published by me as soon as I received it, without comment, and I do not intend it shall come from me, while I believe in Joseph Smith’s revelations. I do believe that bro. Brigham errs in judgement.” [Emphasis in original]

“When there is a want of union,” Hyde interjected, “it requires us to speak plain.

bro. Pratt does not claim any vision or revelation, but keeps within the scope of Joseph’s revelations. .. . I see no necessity of rejecting Joseph’s revelations, or going to War with the living ones, that is the nearest to us . . . I do not see any contradiction or opposition between B. Young & J. Smith.

“B. Young must have feelings towards me,” Pratt then said. “I wish the brethren would point out to me where my pamphlet on ‘the Holy Spirit’ is wrong.”

“[W]hen bro. Brigham tells me a thing, I receive it as a revelation,” returned John Taylor. [S]ome things may be apparently contradictory, but are not really contradictory.”

“It was the Father of Jesus Christ that was talking to Adam in the garden,” Pratt pressed on. “B. Young says that Adam was the Father of Jesus Christ, both of his spirit and Body, in his teachings from the stand. Bro. Richard publishes in the Pearl of Great Price, that another person would come in the meridian of time, which was Jesus Christ.”

“David in spirit called Jesus Christ, Lord,” Hyde offered. “How then is he his Son? It would seem a contradiction, I went to Joseph and told him my ideas of the Omnipresence of the Spirit, he said it was very pretty, and it was got up very nice, and is a beautiful doctrine, but it only lacks one thing, I enquired what is it bro. Joseph, he replied it is not true.” [Emphasis in origi nal.]

“If Christ is the first fruits of them that slept,” Apostle Taylor similarly commented, “there must be some discrepancy, he must have resumed his position, having a legitimate claim to a possession somewhere else, he ought not to be debarred from his rights. The power of God was sufficient to resusci tate Jesus immediately, and also the body of Adam.”

Perhaps anticipating a drawn-out exchange, Orson Hyde announced, “We have come here to arrange that discourse, to the sanction of bro. Young, that it may go forth under the sanction of bro. Pratt . . .

is he willing to put that discourse in shape to recall or qualify certain points of doctrine, not extorted, but in an easy way to show reflection, and that truth has led him to make that confession, and to leave bro. Young out as a dictator, and what would be satisfactory to bro. Young I am pleased with the leniency extended by bro. Young to bro. Pratt, it is more than has been extended to me, or others.

Despite Hyde’s attempted reconciliation, Pratt remained uncompromising. “I have heard brother Brigham say,” he remarked, “that Adam is the Father of our Spirits, and he came here with his resurrected body, to fall for his children, and I said to him, it leads to an endless number of falls, which leads to sorrow and death: that is revolting to my feelings, even if it were not sustained by revelations . . . [AJnother item, I heard brother Young say that Jesus had a body, flesh and bones, before he came, he was born of the Virgin Mary, it was so contrary to every revelation given.”

As Pratt paused, Hyde turned to George A. Smith. “Bro. Geo. A. Smith just tell us what will be satisfactory to the Church?”

“[F]or him to acknowledge Brigham Young as the President of the Church, in the exercise of his calling,” Smith informed. “[B]ut,” he declared, “he only acknowledges him as a poor drivelling fool, he preaches doctrine opposed to Joseph, and all other revelations. If brigham Young is the Presi dent of the Church, he is an inspired man. If we have not an inspired man, then Orson Pratt is right . . . The only thing,” he continued, ” is for bro. Pratt to get a revelation that bro. B. Young is a Prophet of God.”

“I don’t think,” Elder Snow added, “that any light can come to bro. Pratt, while he resists it.”

“I did make a confession with my heart,” Pratt conceded. “I am only an individual, I can not possibly yield to say I have published false doctrine.

I did say it was only my belief, and not revelation, I thought I could go on with the Twelve, and preach and exhort, I leave it entirely in the hands of the Church, I am willing to take out the article, but not willing to say I have taught false doctrine. I have been in the Church many years, and have learned that so long as we want to keep things smooth, we can do so, any modification you feel to make in that sermon, will be right, even to cutting it down one half.

“I feel,” remarked Hyde, “you will yet acknowledge that you have taught false doctrine. I dont think you will receive a revelation, only thro brother Brigham, and you will yet confess that you have stubbornly resisted the Council. I tell you, you will not get a revelation from God on the subject. … ”

“I have wondered why the Lord could not have cooked up something easier,” Apostle Woodruff admitted, “than to see the human family going to hell, or to send his Son to be crucified. I would follow the leader and do the best I could.”

“We will dress and pray,” Hyde followed, “then have that sermon, and read over item by item, and see what will agree with bro. Pratts conscience.”

“I don’t like any patching,” Elder Taylor rejoined, “but follow the dictates of our Presidency, I don’t believe in having things thrown out on bro. Brigham. If that mouthpiece has not power to dictate, I would throw all Mormonism away, all that can be asked is to carry out the doctrine in this sermon.”

“I have always felt,” Pratt responded, “if I can be convinced, nothing would give me greater pleasure than to make a confession.”

Wilford Woodruff placed the 29 January sermon with secretary Thomas Bullock. Soon, vested in their temple robes, all present unitedly formed a close prayer circle, and Apostle Benson led the sacred ritual. After the prayer, which not unexpectedly centered on Pratt’s rebellion, Hyde invited Bullock to read the lengthy discourse. For the following two to three hours, suggested corrections were offered by various quorum members, discussed, and, when accepted, recorded by Secretary Bullock. The bulk of the Quorum’s corrections consisted of ommiting points of opinion and personal judgement felt to be inappropriate in particular reference to Brigham Young. A few clarifying comments were also incorporated into the new text. When finished, approximately twenty-five percent of Pratt’s controversial remarks had been re moved with the Apostle’s tacit approval. John Taylor moved that the Quorum accept Pratt’s revised confessional sermon. His action was seconded, and then carried by the sustaining vote of those present.

At their showing, Pratt commented, “[B]rethren I must say I am very thankful for the many items that are struck out, if this will suit the Presidency, I pray that from henceforth, I may be one with you, and preach with you.”

President Young had apparently anticipated the course of the Quorum’s actions. Later that evening, with the Twelve, in the Historian’s Office, Young’s enthusiasm was evident. “[T]his day I have seen the best spirit manifested.

I have heard 15 or 16 men all running in the same stream. I was delighted. Tomorrow the Church will be 30 years old, about the age that Jesus was when he commenced his mission.

We are improving, and I just know it, my path is like the noon day sun, and I could cry hallujan! hallujah! Praise to God who has been merciful to us, and conferred on us His Holy Spirit A private member in this church is brighter than the power or Kings and Princes of the world, to secure an eternal existence for ever, written in the Lamb’s book of life.

“[B]ro Orson Pratt,” Young continued, “I want you to do just as you have done in your Apostleship, but when you want to teach new doctrine, to write those ideas, and submit them to me. an if they are correct, I will tell you. There is not a man’s sermon that I like to read [more], when you understand your subject, but you are not perfect,” he said; “Neither am I.”

Pratt handed Young the corrected copy of his discourse and explained which alterations had been included. Young added that he would later see that some few additional remarks were attached to Pratt’s sermon before it appeared in print. Then Pratt asked Young if this would mark the end of all discussion on the subject, or if the affair would be “resuscitated again.” The President assured him that “he never wanted the subject to be mouthed again, and wished those in the room, not to mention it.”[54]

True to his word, Young, aided by Counselors Kimball and Wells, saw to the composition of several brief “Remarks” in the early part of July.[55] The First Presidency’s comments were then appended to the revised text of Pratt’s public confession, with both articles eventually appearing in the Deseret News, Wednesday, 27 July 1860.

Following a short, prefatory note which side-stepped the issues Pratt had raised about Adam-God, the First Presidency quoted verbatim excerpts from the Apostle’s controversial writings. Four references were made to The Seer and one to a small pamphlet he had published while in England in 1851, “Great First Cause, or the Self-Moving Forces of the Universe.” Of the four passages from The Seer, three referred directly to Pratt’s notion of the literal omniscience of God. The fourth dealt with both God’s omniscience and the attendant attributes of godliness. The one quotation from Pratt’s English publication touched indirectly upon the attributes of godliness in their variations and combinations as being “the Great First Cause of all things and events that have had a beginning.” These five excerpts were the only points of Pratt’s theological excesses identified by the First Presidency as incompatible with existent church doctrine and revelation. They did not make reference to the Apostle’s “Holy Spirit,” which also contained ideas Young could not sanction. Within less than five years this pamphlet would be similarly condemned.

“This should be a lasting lesson,” Young and his counsellors said “to the Elders of Israel not to undertake to teach doctrine they do not understand. If the Saints can preserve themselves in a present salvation day to day, which is easy to be taught and comprehended, it will be well with them hereafter.”[56]

In the Fall the Apostle received a call to serve a mission in the Eastern United States. There he was to help financially destitute church converts gather to the West. Three days before his 26 September departure, Pratt met with other general authorities and departing missionaries in the Historian’s Office. Pratt and missionary companion Erastus Snow were customarily blessed by their brethren at the onset of this new church assignment. Then, separating themselves from rank-and-file members, the leading councils re tired to an adjoining prayer room where, as Wilford Woodruff wrote, “we had a very interesting meeting.”

Heber C. Kimball, one of several who thought that Pratt’s revised confession did not adequately address the issue of his erroneous doctrines and stubborn insistence upon unsound notions, asked that the Apostle “make satisfaction to Presidt Young” before leaving the city. Yet Young responded that “he did not wish [Pratt] to make any acknowledgement to him.” Pratt, Young remarked to all present,

was strangely constituted he had acquired a great deal of knowledge upon many things but in other things he was one of the most ignorant men [Young] ever saw in his life He was full of integrity & would lie down & have his head cut off for me or his religion if necessary but he will never see his error untill he comes into the spirit world then he will say Brother Brigham how foolish I was . . .

“I will hold on to Brother Pratt,” Young continued, “& all those my Breth ren of the Twelve notwithstanding all their sins, folly & weaknesses untill I me[e]t with them in my Fathers Kingdom, to part no more because they love God and are full of integrity.”

Pratt said, in turn, “I do not believe as Brother Brigham & Brother Kimball do in some points of doctrine & they do not wish me to acknowledge to others that I do not believe.”

“No,” Young rejoined, “you cannot see the truth in this matter until you get into the spirit world.”[57]

Why was the subject of Pratt’s doctrines again brought up, considering Young’s 5 April admonition to the contrary? Is it reasonable to assume that Kimball was unaware of Young’s request since he had not been present at the time and so felt it important enought that Pratt be once more confronted with his perceived disobedience? Given Young’s and Kimball’s close friendship,[58] it is doubtful the President would not have informed his First Counselor of the entire matter. It is possible that Kimball acted upon his own initiative. Whatever the reasons, Kimball’s statements served to renew the Pratt Young conflict.

IV