Articles/Essays – Volume 12, No. 3

The Imperfect Science: Brigham Young on Medical Doctors

Not long after Utah was linked by railroad with the rest of the country, Brigham Young expressed these views: “Doctors and their medicines I regard as a deadly bane to any community. . . . I am not very partial to doc tors. . . . I can see no use for them unless it is to raise grain or go to mechanical work.”[1] Such an offhand dismissal of what is now a prestigious profession may seem either arrogant or ignorant, but it was typical of the distrust and hostility with which he and his followers generally regarded contemporary medical practice. Yet Brigham Young’s attitude toward doctors and medicine was not as negative as most of his published statements may seem to indicate. When one considers the kind of doctors and medicine he was opposed to, his actual behavior as well as his words, and the changes in his attitude over time, quite a different picture appears. He then emerges as a man of common sense, flexible enough to change his mind in the light of new developments.

There was little in medical practice, orthodox or otherwise, of the early nineteenth century to inspire confidence. Few regular doctors were university trained. Most “physicians” had either a year or two of theory and little practical experience or only an apprenticeship with a doctor. Some, of the “heroic” school, emphasized excessive bleeding, harsh “poison” medicines (calomel, lead, arsenic, and opium, for example), raising blisters with the aid of flies, and brutal surgery—techniques potentially more harmful to the patient than his ailment.[2]

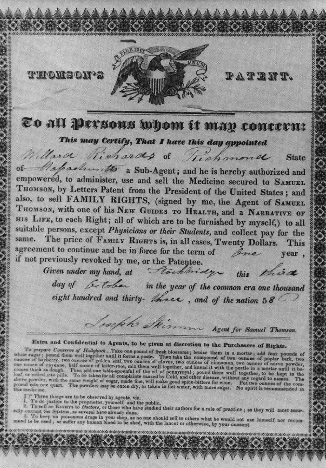

With treatment so unpalatable and in the absence of adequate training and standards, a number of alternative medical approaches arose—homeopathy, hydropathy and the eclectic approach, among others. Perhaps most influential was the Thomsonian system, which emphasized treatment by herbs. Vomiting, purging, and the application of heat (inside and out) were the basic techniques. While these non-orthodox approaches were no more likely to effect cures, they were less likely to do the patient severe damage.[3]

Thomsonian medicine and Mormonism meshed in many ways, both geo graphical and philosophical[4] and several Thomsonian doctors rose to high positions in the Mormon church. Frederick G. Williams, counselor to Joseph Smith in the First Presidency; Levi Richards, Joseph Smith’s personal physician; and Levi’s brother Willard Richards, appointed an apostle in 1840 and counselor to Brigham Young in 1847, are notable examples. Brigham Young shared the views of these Mormon Thomsonians. He once said that Thom sonianism was as much better than the old system of doctoring as the gospel was better than sectarianism and as lobelia was better than calomel.[5]

Adding faith, prayer and priesthood administrations, Young repeated the Thomsonian recommendations—rest, mild food, purging, herbs—throughout much of his life. In 1846, he wrote to the soldiers of the Mormon Battalion: “If you are sick, live by faith, and let surgeon’s medicine alone if you want to live, using only such herbs and mild food as are at your disposal.”[6] Members of the Mormon Battalion indeed suffered from poor medical attention. Arsenic and calomel were forced upon them by Dr. George B. Sanderson, who allegedly threatened to cut the throat of anyone administering medicine without his orders, thus preventing the men from receiving alternate forms of treatment. Yet the members of the Battalion were able to respond with a measure of humor as well as anger. A song written by Levi Hancock includes these verses:

A Doctor which the Government

Has furnished, proves a punishment!

At his rude call of “Jim Along Joe,”

The sick and halt, to him must go.Both night and morn this call is heard;

Our indignation then is stirr’d,

And we sincerely wish in hell,

His arsenic and calomel.[7]

Brigham Young no doubt learned of these unpleasant experiences from re turning members of the Battalion.

The first health law passed in Utah in 1851 reflects Brigham’s aversion to the “poison” medicines used by orthodox doctors. Probably drafted by Wil lard or Phineas Richards, both members of the Legislature, it provided stiff penalties (not less than $1,000 and not less than one year at hard labor) to anyone giving “any deadly poison . . . under pretence of curing disease” without first explaining its nature and effects in plain English and procuring the “unequivocal approval” of the patient—a pioneer truth-in-labeling or full disclosure law.[8]

In a general epistle in 1852 Brigham Young offered this advice:

When you are sick, call for the Elders, who will pray for you, anointing with oil and the laying on of hands; and nurse each other with herbs, and mild food, and if you do these things, in faith, and quit taking poisons, and poisonous medicines, which God never ordained for the use of men, you shall be blessed.[9]

The “poisonous medicines” referred to here were probably those used by orthodox physicians—arsenic, the opiates and especially calomel. “If the people want to eat calomel,” he said, “let them do it and be damned. But don’t feed it to any of my family. If any doctor does and I know it I would kill him as quick as I would for feeding arsenic.”[10] He described calomel as being just as deadly a poison as arsenic but not as quick. Lobelia, in contrast, contained little or no poison. “I will give $5000 dollars,” he said, “for the 16 part of an oz of poison that can be extracted out of all the lobelia in this valley.”[11] Reluctantly he conceded that in rare instances calomel might be beneficial:

But there is constitutions, and situations in life, wherein you may administer calomel to persons, and it will do them good when nothing else will. But is it good in every case? No. Not one in fifty thousand, but we will reduce that and say one to five thousand. It will produce death in five thousand where it will do good only to one person.[12]

It might also “cure some mean person, a person that would not be happy unless they were trying to be miserable.”[13]

In a long analogy comparing the saving of souls to the saving of bodies, Brigham urged the elders to “save the sick like a good physician, and not kill them by dosing down the medicine as do some of our doctors.”[14] Too much medicine was worse for the system than too much food.[15] He recommended “a simple herb drink” for sick children[16] and even urged the production of more honey as medicine.[17]

One of Brigham Young’s favorite themes in his sermons was the prevention of illness by adhering to the Word of Wisdom and following common sense rules of health. He recommended the boiling of water, a sensible and plain diet and the right combination of work and rest.[18] He taught that much illness among the Saints was of their own making. When illness did strike, despite efforts to avoid it, the first line of defense was faith in the healing influence of the administrations of the elders. “Instead of calling for a doc tor,” he said, “you should administer to them by the laying on of hands and the anointing with oil.”[19]

The power of administering to the ill and exercising faith in their behalf was not limited to males. “It is the privilege of a mother,” he said, “to have faith and to administer to her child; this she can do herself, as well as sending for the Elders to have the benefit of their faith.”[20]

Yet Brigham Young never saw reliance on faith and administration as sufficient. As with other ventures, works must be added to faith. Brigham often chided the members for excessive reliance on the Lord and insufficient self-reliance:

You may go to some people here, and ask what ails them, and they answer, “I don’t know, but we feel a dreadful distress in the stomach and in the back; we feel all out of order, and we wish you to lay hands upon us.” “Have you used any remedies?” “No. We wish the Elders to lay hands upon us, and we have faith that we shall be healed.” That is very inconsistent according to my faith. If we are sick, and ask the Lord to heal us, and to do all for us that is necessary to be done, according to my understanding of the Gospel of salvation, I might as well ask the Lord to cause my wheat and corn to grow, without my plowing the ground and casting in the seed. It appears consistent to me to apply every remedy that comes within the range of my knowledge, and to ask my Father in heaven, in the name of Jesus Christ, to sanctify that application to the healing of my body.[21]

The available remedies, in Brigham’s view, included mild foods, herbs, fasting, resting, cleansing and patience in waiting for nature to heal the body—but not the attendance of regular doctors nor their strong medicines.

Brigham Young called the regular medicine of his day “the most imperfect of any science in existence.” Not only did the doctors grossly misunderstand and misapply medication; they did not even recognize so elementary a principle as individual variations. “Doctors make experiments/’ he said, “and if they find a medicine that will have the desired effect on one person, they set it down that it is good for everybody, but it is not so, for upon the second person that medicine is administered to, seemingly with the same disease, it might produce death.”[22]

Surgery was perhaps necessary at times for essentially mechanical procedures, like extracting teeth or setting bones, but doctors no more understood “the system of man” than they did the heavens. “A worse set of ignoramuses do not walk the earth.”[23] He was not impressed with their supposed learning. In an 1861 sermon he said:

I suppose there are physicians here laughing in their sleeves and thinking what a pity it is that brother Brigham was not a studied physician. A studied fool you mean—a learned fool. When you come to the real knowledge I know more than ye all and do not brag one particle. I could put all the real knowledge they possess in nut shell and put it in my vest pocket, and then I would have to hunt for it to find it.[24]

Even the modicum of knowledge he was willing to concede to the doctors was, in his opinion, mishandled. They put the ability into the hands of a few and kept the rest ignorant. Useful medical knowledge should be imparted to all, he said to the Board of Health; those unwilling to share their knowledge were “corrupt.”[25]

He asserted that any community in which the people doctored themselves “according to nature and their own judgments” would experience less sick ness and death than a similar community cared for by regularly qualified physicians—even omitting consideration of the power of faith in healing.[26] If the Saints were to fully cultivate the gift of healing, “every doctor might be removed from our midst.”[27] In 1852 the Deseret News had cheered when doctors gave up trying to make a living in Utah and moved on.[28] In 1869 Harper’s Weekly reported Brigham’s claim that “at Salt Lake they had no sickness till the doctors came. Then they, being too lazy to delve and hoe like others, made people ill, in order to get a living by doctoring them!”[29]

Brigham’s own experiences bore witness to the value of both faith and knowledgeable self-care. He experienced recovery from illness through administration on several occasions and was once saved from death by the quick-thinking action of his wife in applying mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. His own ability to reset his dislocated shoulder with the help of some brethren is a good example of self-reliance.[30]

This distrust of the medical profession was justified in Brigham Young’s mind not only by the low standards among regular doctors but also by what he had heard from Joseph Smith, his revered prophet. In 1843 Smith had declared:

The doctors in this region don’t know much . . . and I take the liberty to say what I have a mind to about them. They won’t tell you where to go to be well; they want to kill or cure you to get your money. Calomel doctors will give you calomel to cure a sliver in your big toe, and they do not stop to know whether the stomach is empty or not; and calomel on an empty stomach will kill a patient. . . .[31]

Joseph had good reason to feel so strongly about the effects of calomel: his brother Alvin had been treated with calomel which then lodged in his upper bowels and apparently was responsible for his death.[32] Joseph Smith’s own recommendations for healing contained many of the same elements evident in Thomsonian medicine and in Brigham Young’s approach—common sense, self-reliance and mild rather than harsh remedies. He attributed his own success in administering comfort in “thousands” of cases of sickness to the patients’ unreserved confidence in him and to the fact that he “never prescribed anything that would injure the patient, if it did him no good.” “People will seldom die of disease,” he explained, “provided we know it seasonably, and treat it mildly, patiently and perseveringly, and do not use harsh means.”[33]

On top of this reinforcement was a series of experiences that quite consistently showed regular physicians to be unreliable at best, enemies of the Kingdom at worst. As Brigham Young started for his mission in England in 1839, his fellow apostle Heber C. Kimball was overdosed with a tablespoon of morphine by an intoxicated doctor. Brigham nursed his unconscious then semi-comatose companion throughout the night. So profuse was Heber’s perspiration that his underclothing had to be changed five times. Brigham had another reason for disliking this doctor, who expressed sympathy for the poverty and ill health of the Mormons nearby, but “did not have quite sympathy enough to buy them a chicken or give them a shilling, though he was worth some four or five hundred thousand dollars.”[34]

In the 1850s, Garland Hurt, an unfriendly Indian agent who helped instigate the Utah War, was also a regular physician. In 1866, another regular doctor, King Robinson, contested Mormon land claims at Warm Springs and after being evicted, filed a suit against the city in federal court.[35] Such emotional incidents did nothing to mitigate the negative associations already established in Brigham’s mind.

Despite these unpleasant associations and his outspoken verbal denunciation of regular doctors, in practice, Brigham Young was able to manifest some flexibility. His own relationships with medical people and the advice he gave them about practicing medicine varied considerably. Some doctors, even orthodox ones, seem to have enjoyed his approval and encouragement and even his friendship.

Samuel Sprague was a close companion of Brigham Young and was prob ably, although not certainly, a regular doctor. He served as camp physician during the trek west, and Brigham conferred with him often about the health of the camp. He was with Brigham almost constantly in his travels around the Territory except when sent on specific missions of his own. He accompanied Brigham to Fillmore in 1855 where he provided medical attention to members of the Territorial Legislature, local citizens and the Indian chief Kanosh.[36] Surely his medical work was not undertaken without Brigham’s approval. Sprague probably cannot be considered a full-time physician.

John Bernhisel, an orthodox doctor and firm advocate of copious bleeding, did not seem to incur Brigham’s direct displeasure either. He was elected delegate from Utah to the House of Representatives several times in the 1850s—which indicates either his high standing with the church leadership or an attempt to channel his energy into more “productive” activities than medicine.[37]

Washington Franklin Anderson, a non- (or possibly ex-) Mormon who was perhaps the most prominent Utah physician of the nineteenth century, enjoyed Brigham Young’s confidence and approval from the very first. His daughter recorded the following:

On his arrival in Salt Lake City, in 1857, my father identified his interests with this community. In a conversation with Brigham Young he made it plain to him that he was not a convert to the so-called “divine” part of Mormonism, but that he admired the law and order that prevailed under his leadership. Brigham Young responded by slapping him familiarly on the shoulder, and assured him that his rights as a citizen would be protected as long as he wished to remain in Utah and practice his profession.[38]

On the other hand, George W. Hickman, who had a medical degree from Oberlin College, joined the Mormon church and settled in Utah County, was counseled by Brigham Young “not to practice medicine because he [Young] wanted to teach the people faith and dependence upon God. . . . This was a stunning blow to a young man who had spent years in preparation for a profession suddenly to have his staff knocked from under him.”[39] Although poorly suited for agricultural life, he gave up his practice, only resuming it gradually and then feeling that he was not entitled to charge for his work.

Brigham was less than encouraging when replying to an inquiry from Dr. David Adams of Fairfield, Illinois. Dr. Adams was interested in Mormonism and wished to move to Utah, bringing with him a hundred people and hoping he could earn his living practicing medicine there. Brigham replied,

As to supporting a family by medical practice, we have physicians who find considerable employment, yet it is no uncommon thing to see them at work in the canyons getting out wood, plowing, sowing, or harvesting their crops, which, I think betokens a healthy state.

In addition to this hint that men were to earn their living primarily by the “sweat of their brow” rather than by doctoring, Brigham Young went on to express his distrust of doctors in general, even implying that they may kill patients prematurely:

. . . a man may always be dying and yet be alive, yet never alive but always dying, until some friendly physician shall interpose and quietly put him away according to the most approved and scientific mode practiced by the most learned M.D.’s. . . . As an individual, I am free to confess that I would much prefer to die a natural death to being helped out of the world by the most intelligent graduate, new or old school, that ever scientifically flourished the wand of Esculapius or any of his followers.[40]

Brigham’s attitude toward women practicing medicine was more encouraging. Caring for the sick, especially attending at childbirth, was congruent with what he envisioned as women’s role, so he set apart several women as midwives for their communities.[41] Elizabeth Ramsay, called to act as midwife, nurse and doctor in St. Johns, Arizona, performed autopsies as well, despite having had no medical training.[42]

While midwifery was acceptable, female professional physicians were not encouraged to practice full time in the early years—at least not for pay. Nette Anna Furrer, a nurse, graduated from Geneva Hospital as a physician and surgeon and studied at Leipzig and Constantinople. She joined the Church in her native Switzerland in 1854, came to Salt Lake in 1856 and married John Cardon. When she and her husband spoke to Brigham Young about their plans to move to the Weber Valley, he told her that her mission was to care for the sick and needy without payment, “and great would be her blessings.” Like George Hickman, she followed the counsel of the prophet and spent her life in giving medical service to others.[43]

Within a few years women were receiving stronger encouragement. In January 1868 in a general epistle to the church, Brigham suggested that women be trained in anatomy, surgery, chemistry, physiology, midwifery, the preservation of health and the properties of medicinal plants.[44] “The time has come for women to come forth as doctors in these valleys of the mountains,” he said.[45] This was an accurate description of what was taking place. Eliza R. Snow insisted that for women to be on a par with men in the medical profession they must have the same training, the same degrees. Citing the prophet, she said that “President Young is requiring the sisters to get students of Medicine,” and urged those who could undertake formal training to do so.[46]

The motivation behind this movement came not so much from a desire to promote equal opportunity for women as from a desire to head off the influence of Gentile doctors and especially to keep obstetrical care as a female province. Eliza R. Snow pushed for expanded training of midwives “so that we can have our own practitioners, instead of having gentlemen practitioners.”[47] She also stated,

We want sister physicians that can officiate in any capacity that the gentlemen are called upon to officiate and unless they educate themselves the gentlemen that are flocking in our midst will do it.[48]

Mormon women, then, were doubly qualified by gender and by religion for this work. Romania Bunnell Pratt Penrose and Ellis Reynolds Shipp were two of the first women called by Brigham Young to travel east for medical training.[49]

As late as 1869, President Young was still far from enthusiastic about the use of doctors by the members of the Church, but in the following advice he recognizes that some of the Saints were indeed consulting physicians:

Learn to take proper care of your children. If any of them are sick the cry now, instead of “Go and fetch the Elders to lay hands on my child!” is, “Run for a doctor.” Why do you not live so as to rebuke disease? It is your privilege to do so without sending for the Elders. You should go to work to study and see what you can do for the recovery of your children.[50]

This was in line with earlier statements emphasizing self-reliance. Brigham said that every good Church member who is magnifying his calling and keeping the commandments should be his or her own physician, should “know their own systems, understand the diseases of their country, understand medicine and they ought to know enough to treat themselves and their neighbors in that way that they will live as long as it is possible for them to live.”[51]

It is misleading, however, to take such statements in isolation. At the same time he was encouraging the Saints to exert their faith, call in the elders, use only mild medication and take advantage of Mormon midwives, he was quietly, perhaps reluctantly, recognizing that times were changing. In 1867 he called Heber John Richards and Joseph S. Richards, sons of Willard Richards, to go to Bellevue Medical College in New York. By 1871 Heber was back in Salt Lake in practice with Dr. Washington F. Anderson.[52] In 1872 Brigham sent his nephew, Seymour B. Young, to attend the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Brigham’s growing acceptance of doctors and medicine was probably in response to the changes he observed around him. The continuing efforts of some conscientious regular doctors (Anderson, Bernhisel and probably Sprague, for example) may have contributed to a softening of his attitude.[53] The coming of the railroad, the development of the mining industry and the founding of hospitals (by non-Mormon churches) to meet the growing health problems in Utah, along with an increasing population of Gentiles—and Gentile doctors—meant that the Saints were likely to need more modern and efficacious alternative help than their own homestyle remedies and practices could give them. Just as he had warned his flock away from Gentile lawyers and schools, Brigham was concerned lest they become dependent upon doc tors not of the faith. He was no doubt aware of the improving level of medical care and a diminution in the excesses of the old “poison” doctors’ methods, including such medical advances as anesthesia and antiseptic surgery.

Brigham’s changing attitude toward orthodox medicine was most dramatically demonstrated when Dr. Seymour B. Young, his nephew, attended him throughout the last three years of his life. During his final illness he was attended, not only by Seymour Young, but by Washington F. Anderson and two other non-Mormon doctors, Joseph Mott Benedict and his brother Fran cis Denton Benedict. Brigham even requested injections of a mild opiate into each foot to alleviate pain.[54]

When all is considered, the remarkable thing is not that Brigham Young distrusted medical doctors—how could he resist the cumulative force of the thoughts and experiences of his day?—but that he proved to be flexible. Here, as in other facets of his life, Young was capable of compromise, of reevaluation when conditions changed. Faced with steadily improving medical standards and an increase in the number of regular doctors (who attracted some Mormons), he could see the writing on the wall. Had he lived longer, he likely would have announced the compromise position that came to be identified with Mormonism: Follow the Word of Wisdom and common sense, call in the elders of the church to administer to the sick, obtain the best medical advice and treatment available, recognize God’s hand in all things.

[1] Journal of Discourses [JD], 26 vols. (London, 1854-86), 4:109, 3 Aug. 1869.

[2] John Duffy, The Healers: The Rise of the Medicine Establishment (New York: McGraw Hill, 1976).

[3] Samuel Thomson, A Narrative of the. Life and Medical Discoveries of the Author (Boston: printed for the Author, 1933).

[4] See John Heinerman, “The Mormons and Thomsonian Medicine: An Experiment in Practical Religion,” Herbalist 1, 5 (1976): 177-83.

[5] Brigham Young Secretary Journals, 2 April 1862, typescript, Church Archives, p. 262.

[6] Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War, 1846-1847 (n.p., 1881), p. 146.

[7] Tyler, p. 183.

[8] Offenses Against Public Health; Acts, Resolutions and Memorials Passed at the Several Annual Sessions of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah 1850-1855, Chapter XXXII, Title IX, Sections 106, 107.

[9] Seventh General Epistle of the Presidency, 18 April 1852, in James R. Clark, Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1833-1964, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1965), 2:98.

[10] Notes of Brigham Young’s medical lecture to the Board of Health at Great Salt Lake City, December, 1851, Wilford Woodruff’s journal.

[11] Sermon, 16 June 1861, typescript, Church Archives, p. 3.

[12] Sermon, 16 June 1861 p. 3.

[13] Brigham Young Secretary Journals, typescript, Church Archives, 2 April 1862, p. 261.

[14] JD 9:125, 17 Feb. 1861.

[15] JD 13:155, 14 Nov. 1869.

[16] JD 14:109, 8 Aug. 1869.

[17] Addenda to the Fifth General Epistle, April 16, 1851, in Clark, Messages of the First Presidency, 2:75.

[18] JD 19:67, 12:122, 13:153.

[19] JD 18:71-72.

[20] JD 13:155, 14 Nov. 1869.

[21] JD 4:24, 17 Aug. 1856.

[22] JD 15:225, 9 Oct. 1872.

[23] Notes of Brigham Young’s medical lecture to the Board of Health at Great Salt Lake City, Dec. 1851, Wilford Woodruff’s journal, Church Archives.

[24] Sermon, Bowery, 16 Jan. 1861, pp. 7-8.

[25] Notes of Brigham Young’s medical lecture to the Board of Health at Great Salt Lake City, Dec. 1851, Wilford Woodruff’s journal, Church Archives.

[26] JD 13:142, 11 July 1869.

[27] JD 14:108, 8 Aug. 1869.

[28] Deseret News, 18 September 1852

[29] Harper’s Weekly, v. 13, 2 Oct. 1869.

[30] Elden J. Watson, ed., Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1801-1844 (Salt Lake City: Elden J. Watson, 1968), pp. 49, 67, 110, 124-5.

[31] Journal History, 13 April 1843.

[32] Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith by His Mother (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), p. 88.

[33] Journal History, 19 April 1843.

[34] Watson, p. 53.

[35] Robert T. Divett, “Medicine and the Mormons,” Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 15 (January 1963), pp. 6-8.

[36] Blanche E. Rose, “Early Utah Medical Practice,” Utah Historical Quarterly 10 (1942), pp. 15-16. Christine Croft Waters, “Pioneering Physicians in Utah, 1847-1900” (M. A. thesis, University of Utah, 1976) lists Samuel Sprague as an orthodox physician but gives no indication of his having attended medical school.

[37] Divett, p. 5.

[38] Belle A. Gemmell, “Utah Medical History: Some Reminiscences,” California and Western Medicine 36 (January 1932), p. 4.

[39] From the journal of Josephine Hickman Finlayson, his daughter, in “Pioneer Medicines,” Heart Throbs of the West, 12 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1939-1950, 7:210-11.

[40] Deseret News, 13 Dec. 1851.

[41] See “Pioneer Midwives,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 20 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1958-1977), 6:361-560 for many examples of women specifically called by Brigham Young to fulfill this duty.

[42] Our Pioneer Heritage, 6:436.

[43] “Pioneer Women Doctors,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 6:398.

[44] Brigham Young, General Epistle, January-February 1868, Church Archives, p. 26.

[45] Keith Calvin Terry, “The Contribution of Medical Women During the First Fifty Years in Utah,” Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1964, p. 46 cites this reference as JD 17:21.

[46] Women’s Exponent 2 (16 Sept. 1873), p. 63.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Salt Lake Stake (General or Cooperative) Retrenchment Association minutes, 1871-75, 13 September 1873, LDS Church Archives.

[49] Chris Rigby Arrington, “Pioneer Midwives,” in Claudia L. Bushman, ed., Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah (Cambridge, Mass.: Emmeline Press, 1976); and several essays in Vicky Burgess-Olson, Sister Saints (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1978).

[50] JD 13:155, 14 Nov. 1869.

[51] Sermon, Bowery, 16 Jan. 1861, pp. 3-4.

[52] An Enduring Legacy (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1978), 1:67-68.

[53] Whitney Blair Young, “A History of the University of Utah College of Medicine” (Thesis for the Medical Doctorate, Kansas University, 1963), p. 12.

[54] See Lester E. Bush, Jr., “Brigham Young in Life and Death: A Medical Overview,” Journal of Mormon History 5 (1978), pp. 90-96 for an account of Brigham’s last few years and death.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue