Articles/Essays – Volume 12, No. 3

A Peculiar People: The Physiological Aspects of Mormonism, 1850-1875

It was nearly sunset when young Dr. Roberts Bartholow passed through Salt Lake City. Having the “good—or ill—fortune to be one of the expeditionary corps, dispatched in the summer of 1857 to Utah,” Bartholow had weathered “a winter of sore privations” with the Fifth Army “at Bridger’s Fort.” Now, late in June 1858 he had “the doubtful satisfaction of marching through the deserted city of Great Salt Lake.” Brigham Young, he later recalled, “to give an appearance of reality to the insurrection,” had “influenced his followers to abandon their homes and move to the south ward.”[1]

A satisfactory resolution to the “Utah War” had been negotiated some days earlier, so it was not long before “the great Mormon herd” began to return.

For many days a vast dust cloud . . . marked their progress. On foot, on horseback, in wagons, with cattle and horses and all the movable paraphernalia of their farms, the Mormon host journeyed northward. On our way to the post of Camp Floyd, we passed through the whole concourse.

As a result, Bartholow wrote, we had an “opportunity as could not occur again of seeing the material of which the Mormon nation is constituted.”[2] Bartholow’s observations on this group of refugees, later included in a report on the “physiological” aspects of Mormonism, received wide distribution. First published among the Senate Documents as the Surgeon General’s Statistical Report (1860), it was almost immediately reprinted in medical journals all over the United States, eventually finding its way into the Medical Times & Gazette of London and into the popular nonmedical periodical De Bow’s Review.[3]

After this first wave of attention, a derivative report disingenuously simi lar to that of Bartholow but ostensibly prepared by another army surgeon, Charles G. Furley, was published in The San Francisco Medical Press (1863), from which Bartholow-like observations were reprinted widely.[4]

Several years later Bartholow reiterated his initial report in The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer (1867), a short extract of which was reprinted by The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. Bartholow’s indirectly related observa tions on the inadequacies of Mormon medicine were also carried in brief notes in both the British Medical Journal and the American Medical Times. Roberts Bartholow, therefore, may be credited as a major influence in the shaping of early medical thinking on “Mormon physiology.”[5]

Curriculum Vitae

An 1852 graduate of the distinguished Medical Department of the University of Maryland, Assistant Surgeon Bartholow had passed the stiff competitive examination required of army doctors “with the highest rank.” The Utah expedition was his first major assignment. From Camp Floyd, in Utah, he went to Fort Ridgely, Minnesota and then back to Fort Union, New Mexico. During the Civil War, he served in hospitals in New York, Baltimore, Washington, D.C. (where he wrote the official Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers) and Nashville, Tennessee. Later a Professor at the Medical College of Ohio, then Professor, Dean and Professor Emeritus at Jefferson Medical College, Bartholow became “one of the foremost physicians of his time.” When ill health forced his retirement at the age of sixty-one, he had garnered many prizes as a medical essayist, an honorary doctor ate of laws, and fellowship in the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh and the Society of Practical Medicine in Paris. He was also cofounder and president of the American Neurological Association, editor of several medical journals and author of many influential medical texts.[6]

However promising this future, the reality of 1858 was considerably less. To date Bartholow’s army experience had been “professionally monotonous,” with little opportunity to exercise his skills. His entertaining and in formative quarterly “sanitary reports” to the Surgeon General were therefore largely taken up with speculative expositions on the etiology of disease and detailed descriptions of the local “medical topography”—i.e., climate, geology, flora and fauna. During the winter of 1857-58, he wrote about the Utah and Snake Indians in the vicinity of Fort Bridger, whom he found “very debased” and “having none of the refined sentiments attributed to Indian heroes in Hiawatha.” He also discussed the mountain men and traders who, like their red brethren, failed to live up to “the reports of poetic explorers.” Such digressions revealed the young surgeon as an energetic observer—and, like so many of his contemporaries, a dedicated “moral physiologist.”[7]

The popular dictum that physical degeneracy was a direct—and inheritable—consequence of moral depravity was unmistakably central to Bartholow’s concept of disease. Excepting those recruits who were “too young to endure the fatigues and privations incident to a military life,” there was one main cause of the disease “constantly operating” among the troops: the men were “broken down by habits of dissipation, by syphilis, [and! by the practice of masturbation, &c.” As an indirect illustration, Bartholow later discussed the first few cases of scorbutus [scurvy—a vitamin C deficiency] encountered on the expedition:

A great variety of causes, apparently opposite in character, are, ceteris paribus, capable of producing scorbutus. The abuse of alcoholic stimulants, and that filthy narcotic, tobacco, a want of cleanliness, indolence, and exhaustion from hard labor, mental despondency, and irregular, ill-prepared food, combine in most cases in the production of the scorbutic cachexy. Upon referring to the previous history of these scorbutic men, a sad catalogue of evil habits is presented—most prominent of all, the long and continued and excessive use of strong drink; ceaseless tobacco chewing. The men belong to that interesting class, heretofore not infrequently mentioned, old, broken-down, and inherently worthless recruits.[8]

Fortunately many of these deleterious influences could be eliminated, given the proper circumstances, and when “whiskey and civilization were left behind,” the health of the command began to improve. It was impossible to escape all evil habits, however, and to Bartholow masturbation and sexual excess [“several teamsters . . . not submitting to strict military rule, were prevailed upon by the charms of filthy squaws”] were a more pernicious cause of disease than the other vices.[9] His first major treatise after leaving the army was On Spermatorrhea (1866), to which he ascribed everything from weakness in the legs, “palpitation” of the heart and gastro-intestinal disorders, to double vision, epilepsy and dementia. His description of the appearance of a chronic masturbator as a person of “pale and sallow tint of skin, .. . a dark circle around the orbits; dilated and sluggish pupils; lustre less eyes” and with a “haggard, troubled, furtive expression” will be seen to have some parallels with this early expedition.[10]

Popular Perspective

In addition to his physiologic philosophy, Dr. Bartholow no doubt brought to his survey of the returning Mormon “herd” some more specific background data. By 1858 a fair amount had been written about the peculiar people and their relic of barbarism. For nearly a decade overland travelers had reported their experiences in Utah to various newspapers and, occasion ally to medical journals. Initially such reports were almost entirely free of commentary on Mormon health and physiognomy. The Saints, if having a “tinge of fanaticism,” most often had been described as “orderly, well disposed, civil and intelligent, industrious, hospitable,” and “verry [sic] social”—just “another striking demonstration of the indefatiguable enterprise, industry and perserverance, of the Anglo-Saxon race.”[11] As Dr. I. S. Briggs of the Ithaca and California Mining Company wrote to The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in 1849, “they are bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh.”[12]

A few travelers, aghast at the discovery of Mormon belief and practices, predicted that if something did not change the Mormon “course, the world’s history will not furnish a parallel of degradation and wretchedness.”[13] Among the earliest observers to suggest that such degradation might already be having an effect was Benjamin Ferris, a federal appointee who spent an unhappy winter among the Mormons in 1852-53 as Secretary of State of the Territory of Utah. Writing the following year about Utah and the Mormons, he characterized Mormon children as “subject to a frightful degree of sickness and mortality,”—”the combined result of the gross sensuality of the parents, and want of care toward their offspring.”[14] This observation, if not the interpretation he applied, was corroborated by the 1850 census. Utah’s death rate was 21 per thousand, nearly 50% higher than the national average and second only to Louisiana among all reporting states and territories. Over a third of the deaths were reported to be among children under the age of five. Not long after, the census report was invoked in another work on Mor monism: Its Leaders and Designs (1857) by ex-Mormon John Hyde. There was indeed a “fearful mortality among the Mormon children” he wrote; Salt Lake City was “nearly as unhealthy as New Orleans.”[15]

John Hyde made another charge, shortly to be very popular but not so clearly supported by the census. Among the Mormons the “proportion of female to male births, is very much in favor of the female sex.” The reverse, he said, was typically the case in “monogamic” countries, but the contrary Mormon experience was entirely predictable “not only from facts observable in all polygamic countries, but also from well-known physiological laws.” Moreover, Hyde had “observed, very frequently, that the more wives a man has, the greater the proportion of female to male children.”[16]

The theoretical basis for Hyde’s remarks derived from the widely accepted observations on middle eastern polygamy published a century earlier by Montesquieu.[17] The basis in fact is not entirely clear. The fact that in Brigham Young’s family at this time girls outnumbered boys two to one is relevant. Yet while by chance there was a preponderance of female births in some Mormon families or communities, the census had revealed no striking overall sex disparities. The ratio of males under age 1 to females under age 1 actually favored the males (104:100). If Hyde and those who followed him based their claim on any real-life enumeration, it may have been the male to-female ratio of those born in Utah and still living there in 1850 (i.e., born within the previous two years or so). By this measure the females were favored, with a M:F ratio of 100:111. In either event, extrapolating birth ratios from those still alive in 1850 was fraught with error. In addition to the massive under-reporting which characterized the territorial census at this time, no consideration is given to differential death rates (by sex) or potential inequalities among the immigrants.[18]

Ex-Secretary of State Ferris levied a second charge, less “physiologic” by twentieth century standards, but relevant at the time: “Nowhere out of the ‘Five Points’ in New York City can a more filthy, miserable, neglected looking, and disorderly rabble of children be found than in the streets of Great Salt Lake City.” While most other visitors during these early years appear not to have felt the children worthy of special comment, one other who did was Lt. J. G. Gunnison, the topographical engineer who wintered with the Mormons in 1849-50. In his generally sympathetic The Mormons . . . in the Valley of The Great Salt Lake (1856), he recounted “in all candor” that “of all the children that have come under our observation, . . . those of the Mormons are the most lawless and profane.” Acknowledging that “circumstances connected with travel, with occupations in a new home, and desultory life, may in part account for this”—factors which no one thought to associate with the mortality rates—Gunnison nevertheless felt this proclivity to give insight into “the quality of the fruit produced by the doc trines.”[19]

Following Gunnison’s lead, John Hyde minimized the importance of seemingly relevant factors in his own hyperbolic picture of Mormon boys:

cheating the confiding, is called smart trading; mischievous cruelty, evidences of spirit; pompous bravado, manly talk; reckless riding, fearless courage; and if they out-talk their father, outwit their companions, whip their school-teacher, or out-curse a Gentile, they are thought to be promising greatness, and are praised accordingly. Every visitor of Salt Lake will recognize the portrait, for every visitor pro- claims them to be the most whisky-loving, tobacco-chewing, saucy and precocious children he ever saw.[20]

About the time John Hyde was leaving Mormonism, Frenchman Jules Remy traveled to Salt Lake City to make some observations of his own. He, too, reported that “births of girls exceed those of boys, a result .. . in perfect conformity with what has been noticed amongst Musselman polygamists.” Additionally, “in spite of the salubrity of the climate, the mortality among children is greater . . . than in many less healthy countries.” And, as also previously noted, “the Mormon children are far from being models of can dour and innocence,” a circumstance attributed by Remy to bad examples, inadequate schooling and insufficient parental time and capacity. In particular, the “moral condition of the male children [seemed] to present some unpleasant features,” but this was the exception in “a society in which public order, pure morality, and external decorum” were “striking.”[21]

It is clear from some of his remarks that Dr. Bartholow was familiar with at least some of these contributions to the fledgling field of Mormon anthropology. He surely must also have been sensitized to the general subject by his conversations at Fort Bridger (Camp Scott) during the winter of 1857- 58 with Dr. Garland Hurt, the anti-Mormon Indian Agent recently fled from Utah.[22]

The New Race

What then was Bartholow’s impression as he passed by the “concourse” of Mormonism enroute to Camp Floyd? The “appearance and opinions” of the procession of returning refugees “were so at variance with the rest of mankind, that the first impression made on our minds was, that the Mormon people is a congress of lunatics.”[23]

In his next quarterly sanitary report, Bartholow expanded considerably. Following the routine recitation of local topography, climate, and fauna, he proceeded to discuss “the Mormon, of all the human animals now walking this globe, . . . the most curious in every relation.”

Isolated in the narrow valleys of Utah, and practicing the rites of a religion grossly material, of which polygamy is the main element and cohesive force, the Mormon people have arrived at a physical and mental condition, in a few years of growth, such as densely-populated communities in the older parts of the world, hereditary victims of all the vices of civilization, have been ages in reaching. This condition is shown by the preponderance of female births, by the mortality in infantine life, by the large proportion of the albuminous and gelati- nous types of constitution, and by the striking uniformity in facial expression and in physical conformation of the younger proportion of the community. . . . One of the most deplorable effects . . . is shown in the genital weakness of the boys and young men, the progeny of the ‘peculiar institution.’[24]

Among the more striking effects noted by Bartholow was the “impress” Mormonism made “upon the countenance.” The “Mormon expression or style” was

an expression compounded of sensuality, cunning, suspicion, and a smirking self-conceit. The yellow, sunken, cadaverous visage; the greenish-colored eyes; the thick, protuberant lips; the low forehead; the light, yellowish hair; and the lank, angular person, constitute an appearance so characteristic of the new race, the production of polygamy, as to distinguish them at a glance. The older men and women, present all the physical peculiarities of the nationalities to which they belong; but these peculiarities are not propagated and continued in the new race; they are lost in the prevailing Mormon type.[25]

With this report Bartholow broke new ground. As noted above, after publication in the Surgeon General’s Statistical Reports, his observations were reprinted by many other significant journals—under such titles as “Mormonism, In Its Physical, Mental and Moral Aspects,” and “Hereditary Descent; Or, Depravity of the Offspring of Polygamy Among the Mormons.” One version of Bartholow’s report came to the attention of the New Orleans Academy of Sciences, and in December, 1860, they devoted a meeting to the subject. In addition to Bartholow’s report, two other papers were read at the Academy meeting, one by “Prof. C. G. Forshey, of Texas,” and the other by the nationally prominent Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright. Most of the remarks of Forshey and Cartwright were only tangentially related, dealing with the suitability of different races for polygamy and servitude [the “European (or white race of men)” were understood to be “degraded” by both institutions]. Implicit in their comments, however, was acceptance of Bartholow’s assertion that a new “race” was emerging in Utah, or at least a uniquely degraded “permanent variety.”[26]

Dr. James Burns, another member of the Academy, voiced strong and perceptive objections to the implicit assumptions of Bartholow, Forshey and Cartwright, that there was such a thing as a “Mormon race:”

It is incredible, that, in so brief a period, has been produced a well- marked inferior ‘race/ with salient facial angles, low and retreating forehead, thick lips, green areola around the eyes, gelatinous or al- buminous constitution, and the other alleged characteristics. . . .[27]

His experience had “taught him to attribute such signs to practices utterly adverse to those of polygamy.” The “green areola” could well be “chlorosis in maidens, and . . . certain other conditions in women married and unmarried.” “As for the ‘gelatinous or albuminous constitution’,” Burns “had never before [been] acquainted with the term, and . . . he was at a loss to guess what it can mean.” Where, he asked, were the quantitative data needed to satisfy the “rigorous requirements of science.” Before the case for a new race or even “only a variety” could be made, more would have to be known on the age, race, physical and mental characteristics, general habits and modes of living, average number of children and the marriage status of the mothers. Equally important would be information collected over at least a decade on the proportion of children in whom the condition was found— “these, and much more, would be necessary, for anything like scientific purposes.”

DeBow’s Review carried Burns’ criticisms, along with the Forshey and Cartwright papers, when it reprinted Bartholow’s report, but published skepticism appears otherwise to have been essentially nonexistent. The response of the London Medical Times and Gazette was probably more representative. The editors found the reports from Utah “of great value, as showing the effects which complete isolation and a gross religion, whose very essence is Polygamy, have produced on the physical stamina and mental hygiene of that saintly community.”[28] Most of the medical journals simply presented Bartholow’s account without qualification or introduction.

Meaningful quantitative measurements of the type suggested by Dr. Burns were, of course, impossible under the circumstances of western American life—in Utah or elsewhere. Territorial censuses, the closest nineteenth century approximations, were notoriously unreliable. At this point they were also unavailable. While the 1860 census had just been completed, many of its relevant findings were not published for several years. In the interim there was a growing body of first-person accounts.

New York editor Horace Greeley’s overland journey in the summer of 1859 took him through Salt Lake City, and his observations were included in a book published the following year. He found the “phrenological development” of the children “in the average, bad” [this, despite “good” development in the adults], but added that he was told that “idiotic or malformed children” were “very rare, if not unknown.” Regarding the preponderance of female births, “the male saints” held this “a proof that Providence smiles on their ‘peculiar institution’.” To Greeley the more likely explanation was the “preponderance of vigor” of young wives over old husbands.[29]

A year after Greeley’s visit, world traveler Richard Burton, dedicated student of both polygamous societies and holy cities, arrived to make his own study. His The City of the Saints (1861) addressed many of the same “physiologic” questions then in vogue, but reached distinctly different conclusions. The “generally asserted” notion that juvenile mortality ranked “second only to Louisiana” he did not believe ascribable to polygamy. Regarding Ferris’ claim that Mormon youth were a “filthy, miserable, and dis orderly rabble,” his experience was “the reverse. I was surprised by their numbers, cleanliness, and health, their hardihood and general good looks.” As to John Hyde’s caricature, it was “the glance of the anti-Mormon eye pure and simple. Tobacco and whiskey are too dear for children at the City of the Saints.” Most of Hyde’s charges were “too general . . . not to be applicable to other lands.” Moreover, “a youth at many an English public school would have been ‘cock of the walk,’ if gifted with the merits [ascribed by Hyde].”[30] Thereafter the behavior of Mormon boys ceased to be a major focus of attention.

At this rather indecisive juncture, another physician chose to enter the debate. Charles C. Furley, M.D., apparently an assistant surgeon stationed with the army in California, not long before had paid a visit to Salt Lake City and felt “qualified to speak of the results of their peculiar institution, both in their social, physiological and intellectual bearings.” It was, however, “chiefly as a physiologist” that he treated the subject of “The Physiology of Mormonism” in an April 1863 issue of The San Francisco Medical Press. The consequences of polygamy he had found to be “in every aspect of the case, hurtful and degrading:”

A marked physiological inferiority strikes the stranger, from the first, as being one of the characteristics of this people. A certain feebleness and emaciation of person is common amongst every class, age and sex; while the countenances of almost all are stamped with a mingled air of imbecility and brutal ferocity. . . . In the faces of nearly all, one detects the evidences of conscious degradation, or the bold and defiant look of habitual and hardened sensuality.[31]

“Without entering into minutiae,” Dr. Furley offered the following “as a few of the bodily peculiarities that strike the medical man:”

Besides the attenuation mentioned, there is a general lack of color— the cheeks of all being sallow and cadaverous, indicating an absence of good health. The eye is dull and lustreless—the mouth almost invariably coarse and vulgar. In fact, the features—the countenance—the whole face, where the divinity of man should shine out, is mean and sensual to the point of absolute ugliness.

“Nowhere” had he seen anything “more pitiful than the faces of the women here, or more disgusting than the entire appearance of the men.” But the evidences of “natural degeneracy” were even “more palpable in the youthful than in the adult population:”

It is a singular circumstance that the physiognomical appearances of the children are almost identical. The striking peculiarity of the facial expression—the albuminous types of constitution, the light yellowish hair, the blue eye and the dirty, waxen hue of the skin, indicate plainly the diathesis to which they belong. They are a puny and of a scorbutic tendency. The external evidences are numerous that these polygamic children are doomed to an early death—the tendency to phthisis pulmonalis being eminent and noticeable.

Striking yet another familiar chord, Furley closed with the observation that the “feeble virility of the male and the precocity of the female” were notorious, and that as a consequence,

more than two thirds of the births are female, while the offspring, though numerous are not long lived, the mortality in infantine life being very much greater than in monogamous society.

In the three years since Bartholow’s report was published, the new Mormon race, it seems, had lost only their green eyes. Furley’s account was nonethe less deemed newsworthy, and as previously noted his San Francisco Medical Press article was reprinted by a number of major medical journals in the East.[32]

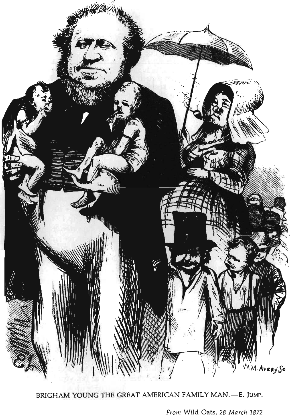

The “pitiful” faces of the Mormon women were becoming a popular theme, in some ways replacing childhood rowdyism as a conspicuous, quasi-physiologic sign of the debasement of polygamy. While by no means a unanimous observation, a clear consensus did emerge: “handsome women and girls [were] scarce among the Mormons of Salt Lake.” The charity with which this was announced varied from William Chandless’ genteel observation in 1857 that “the collected womanhood of the city did not impress me favourably as to the amount of beauty to be found there; but perhaps the fairest stay at home . . .,” to the “array of homely women . . . who were clad as plainly as they look” noted by E. H. Derby a decade later. “Are the Mor mon women pretty?” Dr. E. P. Hingston wrote after a visit in 1864, “Many have asked me the question. Pardon me, Mormon ladies, while I truthfully reply. Some are pretty enough. I regret to say they are so few.” Hingston’s traveling companion, humorist Artemus Ward, also noted “no ravishingly beautiful women present, and no positively ugly ones. . . . They will never be slain in cold blood for their beauty, nor shut up in jail for homeliness.” Even Brigham Young, wrote editor Samuel Bowles in 1865, “considering his opportunities . . . has made a rather sorry selection of women on the score of beauty”—the fact of which Brigham is alleged to have offered as evidence that Mormon polygamy was not carnally motivated. Heber C. Kimball, his counselor and one of the most notorious polygamists because of the size of his harem, “is even less fortunate in the beauty of his wives; it is rather an imposition upon the word, beauty, to suggest it in their presence. . . .”[33]

Such reports never seemed to carry the moral and physiologic urgency as did the other alleged manifestations of Mormon practices. In part this was probably due to the chauvinistic ease with which the subject could be, and was, turned into a joke. Mark Twain, for example, wrote of his visit to Salt Lake City in the early 1860s that he had planned “a great reform here—until I saw the Mormon women:”

Then I was touched. My heart was wiser than my head. It warmed toward these poor, ungainly and pathetically “homely” creatures, and as I turned to hide the generous moisture in my eyes, I said, “No—the man that marries one of them has done an act of Christian charity which entitles him to the kindly applause of mankind, not their harsh censure—and the man that marries sixty of them has done a deed of open-handed generosity so sublime that the nations should stand un- covered in his presence and worship in silence.[34]

As ever, there were many—perhaps most—among those who passed through Mormon country who failed to find the conspicuous signs of physical degeneration by now so widely reported in the medical literature. Chester Bowles, for example, who had accompanied House Speaker Schuyler Colfax to Utah, clearly agreed with the theory behind the doctors’ assertions, but could not go much beyond that:

it is safe to predict that a few generations of such social practices will breed a physical, moral and mental debasement of the people most frightful to contemplate. Already, indeed, are such indications appar- ent, foreshadowing the sure and terrible realization, [emphasis added][35]

Demas Barnes, visiting Utah about the same time, was even more explicit: “Nothing in the apparent physical or intellectual development of the youth or children indicates immaturity, or decay.” But, he added,

Notwithstanding the evident physical and moral prosperity of the community up to this time, I cannot believe but that a general system of polygamy would retard civilization and work the downfall of any advanced nation.”[36]

These less severe judgments of the current state of Mormon physiology were not missed by Dr. Bartholow, now a professor at the Medical College of Ohio. Addressing the Cincinnati Academy of Medicine early in 1867 on “The Physiological Aspects of Mormonism,” he repeated his earlier assessment. Recent visitors to Utah simply had been mislead by a combination of the “beautiful scenery, the wonders of nature, and the delicious climate,” and the “wonderful results” achieved in Salt Lake City:

To see Mormonism as it is and to judge of its legitimate fruits, it should be studied in the villages and towns of other parts of the territory, where the restraints of gentile opinions do not repress the natural growth of the system. There may be seen the new Mormon population—the offspring of polygamy. The cadaverous face, the sensual countenance, the ill-developed chest, the long feeble legs, and the weak muscular system, are seen on all sides and are recognized as the distinctive feature of the Mormon type.[37]

The number of female children, he once again asserted,

is greatly in excess of the male, which is an evidence of the regression in the constitutional vigor of the population. The idiotic and the con- genitally deformed are painfully numerous. These causes of decay, if not interfered with, would extinguish in a few centures the Mormon society. Unfortunately, the strength and vigor of the population is maintained by constant infusions of new blood.

“By order” of the Academy, Bartholow’s discourse was published in the April issue of The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer, from which extracts once again were reprinted in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal—relating particularly to Mormon women who Bartholow reported being told were “chiefly, prostitutes from our Eastern cities.”[38] Thereafter Dr. Bartholow ap parently dropped the subject of Mormonism, moving on through the exceptional career noted at the outset. By the time he left Cincinnati a decade later, he had in addition to many academic accomplishments the “largest and most lucrative” medical practice in the city. As the distinguished professor of materia medica at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia he was constantly in demand as a consultant. Notwithstanding his many successes, Bartholow’s biographers have found him to be a man who “never had an intimate friend or even a close associate. A frigid dignity, a chilly reserve, and an uninviting manner which was not lacking in a suggestion of cynicism and sarcasm, stood during his whole life between the man and the world at large.” It can at least be said of his analysis of Mormonism that he viewed others with an equally sympathetic eye. In addition to the degeneracy he found among his troops, the mountain men, Indians and traders, he also confronted at least one other “excresence upon our body politic—the mixed races of New Mexico.” To judge from his characterization of this group, they may have been even more depraved than the Mormons.[39]

It goes without saying that the Mormons did not perceive themselves in quite the same light as did their critics. Yet, at the level of “physiologic” theory, their views could not have been more similar. The following characterization of the effects of “habits” and “religion” on the varieties of man,” from a series of articles in the Mormon Juvenile Instructor (1868), could as well have been extracted from Bartholow, Furley or others:

Those who have a barbarous form of faith, in which licentiousness, human sacrifices and disgusting orgies prevail, get a corresponding barbarous and cruel expression on their faces. While licentiousness and dissipation amongst every race either civilized or savage, black, brown or white, have always weakened that people, diminished their size and strength, aggravated their peculiarities and shortened their lives; on the other hand, a virtuous life, combined with a true faith well lived up to, has ever developed a superior race of men, robust in body, beautiful in countenance.[40]

Where Mormon and “Gentile” physiologists parted ways was in the cases they found illustrative of these basic principles. In Mormon eyes, “the deadly work of physical degeneracy” was indeed rampant in American society, “until the race is nearly upon the brink of extinction.” But the problem was to be found in the vices of non-Mormon society. In New England, for example, “if you find any children at all, as a rule it is . . . two or three children at the most in the majority of cases, and they, generally sickly and short lived.”[41]

Things were distinctly different in Utah because of the many benefits accruing from the institution of “plural” marriage,

not only . . . upon the grounds of obedience to a divine law, but upon physiological and scientific principles. In the latter view, the wives are even more benefitted, if possible, than the husband physically. But indeed, the benefits naturally accruing to both sexes, and particularly to their offspring, in time, to say nothing of eternity, are immensely greater in the righteous practice of patriarchal marriage than in monogamy. . . .[42]

In the words of Apostle George Q. Cannon, “the physiologic side of the question” was “one, if not the strongest, source of argument in favor” of polygamy:

I have heard it said, and seen it printed, that the children born here under this system are not so smart as others; that their eyes lack lustre and that they are dull in intellect; and many strangers, especially ladies, when arriving here, are anxious to see the children, having read accounts which have led them to expect that most of the children born here are deficient. But the testimony of Professor Park, the principal of the University of Deseret, and of other leading teachers of the young here, is that they never saw children with greater aptitude for the acquisition of knowledge than the children raised in this Territory. There are not brighter children to be found in the world than those in this Territory . . . The offspring, besides being equally as bright and brighter intellectually, are much more healthy and strong.[43]

While no one appears to have felt a pressing need to confirm the grim findings of the 1850 territorial census, additional census reports did continue to appear. By 1866 most of the 1860 data was available, and it raised questions about some of the accepted wisdom on Mormon polygamy. Males continued to be as well represented in the infant population as females, in about the ratio that subsequent study has found to be nearly universal in all societies studied. Decennial ratios from Utah, for example—recalling still the general unreliability of the data—were 1850—104 males under age one to 100 females; 1860—98:100; 1870—105:100; 1880—103:100. Such a finding would not have been a surprise to everyone. As William Hepworth Dixon, editor of the London Athenaeum, wrote after visiting the Mormons in the summer of 1866, “we can happily say, in the light of science, that even in Egypt and Arabia the males and females are born in about equal numbers; the males being a little in excess of the females.”[44]

Death rates were another matter. J. H. Beadle’s vigorously anti-Mormon Life in Utah; Or, the Mysteries and Crimes of Mormonism, published in 1870 based on his fifteen-month residence in Utah, looked well back into the past to find “actual statistics [which show] that the mortality among children was, for many years, greater in Salt Lake City than any other in America, and the death-rate of Utah only exceeded by that of Louisiana.” More recently, “the sexton’s report for October, 1868, the healthiest month in the year, and my first in the city, gives the interments at sixty, of which forty-four were children.”[45]

Mortality rates, especially those of early childhood, are among the least reliable population statistics even in areas where reasonably sophisticated census surveys are possible. In Utah at this time, where one Mormon leader is alleged to have described the data as obtained “mainly by guessing on the part of a gentile officer, who would not go about and count,”[46] reported mortality figures were essentially worthless. It is nonetheless revealing that critics of the Mormons still turned to the 1850 figures which had ranked Utah so high in overall mortality rate. The figures for 1860 were dramatically different, and this difference persisted for the remainder of the century:

| Reported death rate / 1000 total population | ||

| Utah | United States | |

| 1850 | 21.0 | 13.9 |

| 1860 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| 1870 | 10.2 | 12.5 |

| 1880 | 16.4 | 14.6 |

| 1890 | 10.0 | 13.4 |

| 1900 | 11.1 | 13.7 |

Such figures have little meaning. The Utah rates are grossly under-reported, particularly in the decades from 1860 to 1890 during which, it appears, a large percentage of infant deaths were not recorded in the census. If one computes the death rates for infants under age one, and children under age five,— based on the reported deaths and total population in these age groups—Utah still does “better” than the national average. This is solely because of the poor census records—infant mortality rates in Utah become much higher at the end of the century despite better health care, simply because the records are better—but nonetheless reflects directly on the selectivity with which these early records were used.[47]

The alternative to census figures was the type of isolated data, also included by Beadle, obtainable from monthly death notices, newspaper accounts and cemetery records. The best reconstruction of such material for nineteenth century Utah is found in Ralph Richards’s Of Medicine, Hospitals, and Doctors, and is based primarily on an extensive review of cemetery and hospital records in the Salt Lake City area. His findings, which are presented in terms of absolute number of deaths for several important diseases, suggest strongly that the infant and early childhood mortality rates were indeed high in these early years, and that they probably continued so until a number of sanitary reforms were introduced in the 1890s. No meaningful overall rates can be calculated from his figures, but it seems evident that infant death rates were at least as high in Utah as they were in other less developed regions of the American west.[48]

According to Beadle, the Mormons explained the high mortality “by saying that their people are poor and exposed to hardships.” He would add to this that the poverty stemmed from their religion, and that they also neglected responsible medical care:

They claim that “laying on of hands and the prayer of faith” will heal the sick, and, yet, no people within my knowledge are so given to “Thomsonianism,” “steam doctoring,” “yarb medicine,” and every other irregular mode of treating disease.[49]

Army Surgeon W. C. Spencer, at the time stationed at Camp Douglas, just outside of Salt Lake City, had a similar impression. While “the health of the Mormon people is generally good,” he wrote the Surgeon General, “in the city . . . the mortality among the children is quite large.” This he attributed less to epidemics than to “neglect, insufficient food, and the practice of ‘laying on of hands’ . . . to the exclusion of remedial measures.”[50] Unlike most of his predecessors, Spencer did not feel impelled to attribute the problem to intrinsic “physiological” degradation. To him, the Mormons had social and cultural deficiencies, but the impact of these shortcomings was on attitudes and practices—not on physiology.

Dr. Spencer’s superior at Camp Douglas was Surgeon E. P. Vollum, a career army physician about whom very little is known. He had been a military surgeon for twenty years when he arrived in Utah, but the nature and extent of his experience is uncertain. One thing can be said about him: his physiologic perspective was different from that of Dr. Roberts Bartholow. To Vollum “the best known treatment for consumption” was “a year of steady horseback-riding in a mountainous country, and a diet of corn-bread and bacon, with a moderate quantity of whiskey.” Surgeon Vollum’s tour of duty in Utah extended over several years, during which he “traveled over the length and breadth of the Territory, and . . . made an intimate acquaintance with the people of all classes and degrees.” As a result he probably had the most detailed knowledge of Mormon health yet acquired by anyone outside the Mormon community.[51]

Vollum’s “Special Report On Some Diseases of Utah” was published by the Surgeon General in 1875 as part of the Report of the Hygiene of the United States Army. In it he addressed most of the familiar themes. While it was still “perhaps too early to express any mature opinions as to the influence of polygamy .. . on the health or constitution or mental character of the Anglo-Saxon race as seen in Utah,” there were a number of observations which could be made:

as far as the experience has gone, which is long enough to furnish quite a population ranging from twenty-five years downward, no difference can be detected in favor of one or the other [i.e., polygamy or monogamy]. Polygamy in Utah, as far as I can learn, furnishes no idiocy, insanity, rickets, tubercles or struma, or other cachexia, or debasing constitutional conditions of any kind. . . The polygamous children are as healthy as the monogamous, and the proportion of deaths is about the same; the difference is rather in favor of the polygamous children, who are generally, in the city especially, situated more comfortably as to residence, food, air, clothing, their parents being better off than those in monogamy.[52]

One trace of the earlier view reflected a still current view of the nature of heredity:

Some observers imagine they notice a saddened expression of countenance on the Mormon children; that they have not the cheeriness and laughter common to that age; especially that the young women, who here are robust, ruddy, and well made, lack the amiable, bright and cordial countenance characteristic of young women everywhere, and they attribute this supposed dullness of face to the pre-natal influences of the polygamous relation on the mothers. Certainly at times I have thought there was some truth in such a notion.[53]

This was not to suggest that there were no health problems. While “the adult population are as robust as any within the borders of the United States, . . . the weight of sickness falls upon the children, who furnish not less than two-thirds of all the deaths, most of which occur under five years of age.” This “great mortality” was “confined chiefly to the Mormon population,” and like Beadle and Spencer, Vollum thought it could “be traced to absence of medical aid, nursing, proper food for sick children, and neglect of all kinds.” In particular, “the children of Salt Lake City may often be seen in groups insufficiently clad, the lower half of the body bare, playing about in the cold water. . .”—the latter activity especially to be condemned as it lead to catarrhs, pneumonia, fevers, bowel complaints and “necrosis of the tibia” [i.e., death of a portion of the “shin” bone].[54]

Like those before him, Vollum singled out Mormon medical care for special condemnation—”the nonsensical mummery of the ‘laying on of hands, ‘. . . the tea of the sage-brush, and other old woman’s slops. . . .”The results were “as might be expected.”[55] Ironically, at the time of Vollum’s report, Mormons were beginning their transition from primary reliance on priest hood administration, botanic remedies and folk medicine, to acceptance of orthodox, and increasingly scientific medical care. Even then the first Mor mons were studying in medical schools in the East. Perhaps more importantly for the health of Mormon babies, physicians elsewhere were beginning to understand and prevent disease. Notwithstanding Vollum’s expressed concerns, it was not so much cold water as contaminated water that posed the threat—and faulty feeding practices and a host of other hygienic considerations. Excessive deaths among the young, to judge from those enumerated in the census, were due to the same causes prevalent elsewhere: dysentery, pneumonia and diphtheria,[56] about which “orthodox” medicine had been able to do little. In the perceptive words of one early visitor, “homoeopathy and hydropathy succeed by doing nothing; ‘administration’ very likely answers better than over-dosing. . . .”[57] When scientific medicine finally had much to offer late in the nineteenth century, engrained Mormon distrust of orthodox medical practice may have delayed implementation for a few years; but by the early twentieth century Mormons as a group had a death rate substantially below the national average, a distinction they have maintained to the present.

It is not known how widely Surgeon Vollum’s report was circulated—I’ve found no reference to it in contemporary medical journals—, but it seems to mark by coincidence or otherwise the end of the notion of a “Mormon physiology,” at least within the medical literature.[58] Several decades later, Josiah Hickman, a Mormon, conducted “A Critical Study of the Monogamic and Polygamic Offspring of the Mormon People” for his master’s thesis at Columbia University. His rather unsophisticated comparison of large numbers of students supposedly revealed those of polygamous origins to be taller, heavier and superior in intellect. A larger, community-based portion of his study found that polygamous offspring had fewer “physical deformities and . . . mental degeneracy, due to birth and sickness,” and greater professional success than did their monogamist counterparts. More significant, for our purposes, was an introductory note by the editor of The Journal of Heredity, in which Hickman’s findings later were published:

The fact that plural families were restricted by the Church authority to a select class of the population would explain the average superiority of the polygamous families.[59]

In retrospect, that seemed self-evident.

[1] As recounted by Bartholow a decade later, in “The Physiological Aspects of Mormonism, and the Climatology, and Diseases of Utah and New Mexico,” The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer 10:193-205 (April 1867).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Thomas Lawson, ed., Statistical Report on the Sickness and Mortality in the Army of the United States, from January 1855 to January 1860 (Washington, D.C., I860), pp. 301-2; Senate Executive Document 52, 36th Congress, 1st session, pp. 283-304; Medical Times and Gazette (London) 2:190-92 (24 August 1861); The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 63:438-40 (27 December 1860); The Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal 4:343-47 (1861); The Saint Louis Medical and Surgical Journal 19:270-72 (May 1861); Georgia Medical and Surgical Encyclopedia 1:321-23 (November 1860); DeBow’s Review (New Orleans) 5:208-10 (February 1861)

[4] The San Francisco Medical Press 4(13):l-4 (April 1863); The American Journal of Insanity 20:366-67 January 1864); American Medical Times 7A\ (25 July 1863); The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 68:507-9 (23 July 1863).

[5] The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer 10:193-205 (April 1867); The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 76:296 (2 May 1867); British Medical Journal, Vol. 1 for 1861, p. 77 (19 January 1861); American Medical Times 1:432 (15 December 1860).

[6] Biographical data on Bartholow can be found in many places. Three of the most extensive sketches are James W. Holland, M.D., “Memoir of Roberts Bartholow, M.D.,” Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 3d Series, 23:xliii-lii (1904); “Editorial [on Roberts Bartholow, M.D., LL.D.]/’ The Eclectic Medical Gleaner, New Series, 8:81-87 (March 1912); Otto Juettner, Daniel Drake and His Followers (Cincinnati: Harvey Publishing Co., 1909), pp. 260-67; and John R. Quinan, Medical Annals of Baltimore From 1608 to 1880 (Baltimore: Isaac Friedenwald, 1884), pp. 61-62.

Among Bartholow’s more popular books were A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine for the Use of Students and Practitioners of Medicine which went through nine editions (one in Japanese) between 1880 and 1895, and A Practical Treatise on Materia Medica and Therapeutics, which went through eleven editions between 1876 and 1904.

[7] Lawson, ed., Statistical Report, pp. 288-89. On the moralistic foundation of physiologic thinking at mid-century see Richard H. Shryock, “Sylvester Graham and the Popular Health Movement, 1830-1870,” in Shryock, Medicine in America: Historical Essays (Baltimore: Johns Hop- kins Press, 1966, pp. 111-25, and Chapter 3, “The Health Reformers,” in Ronald L. Numbers, Prophetess of Health: A Study of Ellen G. White (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), pp. 48-76. A further extension is discussed in James C. Whorton, “‘Christian Physiology’: William Alcott’s Prescription for the Millenium,” in Bulletin of the History of Medicine 49:466-81 (Winter 1975). While these accounts do not all deal with the mainstream of medical thought and practice, the general philosophy described can be applied to most contemporary physicians.

[8] Lawson, ed., Statistical Report, p. 287. Ironically, Bartholow himself was shortly to lose most of his teeth to a “scorbutic” malady—one of the sore privations at Fort Bridger.

[9] Ibid., p. 284. For perspective see H. Tristam Engelhardt, Jr., “The Disease of Masturbation: Values and the Concept of Disease,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 48:234-48 (Summer 1974).

[10] Roberts Bartholow, On Spermatorrhea: Its Causes, Symptomatology, Pathology, Prognosis, Diagnosis, and Treatment (New York: Wood, 1866), pp. 18-23. The masturbator also had “un- usual development of acne” and “an oblique line extending from the inner angle of the lids -transversely across the cheek to the lower margin of the malar bone,” and an inevitable “atrophy” of the genital organs. While spermatorrhea classically referred to the “flow of semen without copulation,” Bartholow asserted—apropos the case in point—that “excess in natural coitus, as well as masturbation, but by no means so frequently, will produce the same morbid state” (p. 14). On Spermatorrhea was very favorably received by the medical community, receiving many laudatory reviews, and eventually going through five editions.

[11] Quotations from Thomas D. Clark, ed., Off at Sunrise: The Overland Journal of Charles Glass Gray (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1976), p. 63; Dale L. Morgan, ed., “Letters by Forty- Niners,” Western Humanities Review 3:109, 111 (April 1949); Jessie G. Hannon, The Boston Newton Company Venture From Massachusetts to California in 1849 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1969), p. 163; Samuel M. Smucker, Life Among the Mormons (New York: Hurst & Co., ca. 1889), p. 416, citing a New York newspaper account about 1550.

[12] I. S. Briggs, “Medical History of a California Expedition,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 41:479-80 (9 January 1850). Other physicians who wrote about Salt Lake City and the Mormons without noting any peculiar physiognomy included Caleb N. Ormsby of Michigan and Thomas Flint of Philadelphia. See Russell E. Bidlack, Letters Home: The Story of Ann Arbor’s Forty-Niners (Ann Arbor: Ann Arbor Publishers, I960), and Diary of Dr. Thomas Flint, California to Maine, 1851 -1855 (Los Angeles: Reprinted from the Annual Publications, Historical Society of Southern California, 1923), p. 58. The general absence of reports on the Mormons in the major medical journals during these early years is probably itself significant evidence that nothing unusual was observed by those passing through. Certainly there were enough “trained observers;” in 1850 alone over 100 physicians reportedly made the overland trek from Council Bluffs to California, many passing through Mormon country en route. See M. H. Clark, “Mortality on the Platte River,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 47:121-22 (1853).

[13] Morgan, “Letters”, pp. 113-14. It is clear from letters such as this, written in 1849, that while polygamy was not openly proclaimed by the Mormons until 1852, it was a practice visible to at least some visitors several years earlier. Others, such as topographical engineers Howard Stansbury and J. W. Gunnison, who wintered with the Mormons in 1849-50, also became familiar with this Mormon practice. See Howard Stansbury, An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake . . . (London: Sampson Low, Son, and Co., 1852), p. 137, and Lieut. J. W. Gunnison, The Mormons or Latter-day Saints, in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake . . . (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1856), p. 67.

[14] Benjamin G. Ferris, Utah and the Mormons (New York, 1854), p. 249.

[15] John Hyde, Jr., Mornionism: Its Leaders and Designs (New York, 1857), p. 75; Census Reports, 1850.

[16] Hyde, Mormonism, p. 74-75.

[17] Several later commentators on Mormon polygamy, still convinced that a disproportion existed between the sexes from birth, credited Montesquieu with first having made the association elsewhere. John Cairncross, After Polygamy Was Made a Sin: The Social History of Christian Polygamy (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974), p. 107, specifically dates the idea to Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1747).

[18] Census Reports, 1850. Usually the death rate is significantly higher among male babies.

[19] Ferris, Utah and the Mormons, p. 249; Gunnison, The Mormons, p. 160.

[20] Hyde, Mormonism, p. 77.

[21] Jules Remy, A Journey to Great-Salt-Lake-City (London: W. Jeffs, 1861), p. 150. A French edition appeared in 1860, and at least one author has reported an 1857 edition, which I have been unable to confirm. Remy’s impressions may therefore not have been published prior to Bartholow’s arrival in Salt Lake City.

[22] On Hurt see Norman Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859 (New Haven: Yale University, 1960), esp. pp. 49-50. Of potentially greater influence was Dr. Charles Brewer, also a University of Maryland graduate and fellow Assistant Surgeon. Brewer, who eventually replaced Bartholow at Camp Floyd, had traveled for a time with the “Perkin’s train”—part of the ill-fated Fancher party—which was massacred in southern Utah in September 1857 by a combined group of Indians and Mormon militiamen. It is not apparent whether Brewer and Bartholow were in communication prior to Bartholow’s report. See the “Special Report of the Mountain Meadow Massacre, by J.H. Carleton . . .”in which Brewer testifies on the subject, House of Representatives Document 605, 57th Congress, 1st Session.

Finally, there were the increasingly popular fictional accounts of Mormonism, which at least since 1855 had been promoting a stereotype of licentiousness and debauchery. See Leonard J. Arrington and Jon Haupt, “Intolerable Zion: The Image of Mormonism in Nineteenth Century American Literature,” Western Humanities Review 22: 243-60 (Summer 1968).

[23] Bartholow, The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer 10: 194.

[24] Lawson, Statistical Report, p. 301-2. Bartholow illustrated the high infant mortality rate with an example that was very popular with later critics of Mormon polygamy. Among the “large number of children” who had been born to Brigham Young, “a majority” had died “in infancy, leaving twenty-four.” In fact, at the time Bartholow was writing (1858), Young had fathered forty-four children, five of whom (including two sets of twins) had died in infancy. Two others had died at the age of seven, leaving him thirty-seven of his forty-four children, a very reasonable survival rate at the time. Eventually Young fathered fifty-seven children, of whom eight died in infancy, still as least as good a record as found in most of the United States throughout the nineteenth century. Young family data from Dean C. Jessee, ed., Letters of Brigham Young to His Sons (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), Appendix C.

[25] Lawson, Statistical Report, p. 302.

[26] Journals as cited in note 3. The New Orleans Academy of Sciences proceedings were published in DeBow’s Review 30:206-8, with the Bartholow, Forshey, and Cartwright articles following. Newell G. Bringhurst, “A Servant of Servants . . . Cursed as Pertaining to the Priest- hood” (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Davis, 1975), p. 183-84, puts these comments into the perspective of contemporary views on race; Charles A. Cannon also has many relevant comments in “The Awesome Power of Sex: The Polemical Campaign Against Mormon Polygamy,” Pacific Historical Review 43: 61-82 (February 1974), especially pp. 77-79 in which he deals with the physiologic issue.

[27] DeBow’s Review 30:207-8.

[28] Medical Times and Gazette 2:190.

[29] Horace Greeley, An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco (New York: CM. Saxton, Barker & Co., 1860), p. 242.

[30] Richard F. Burton, The City of the Saints (1861), Fawn M. Brodie, ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963), pp. 472-73.

[31] The San Francisco Medical Press 4(13): 1-4 (April 1863). Nothing is known of Furley’s back ground or career; he is not listed in the standard roster of Union officers.

[32] E.g., The Journal of Insanity, The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, and the American Medical Times, as cited in note 4. The feeble virility or genital weakness reported by Furley and Bartholow was difficult to rationalize with the concurrent reports that Mormons were an unusually fertile group. Typically this was ascribed to the women, and allegedly accounted for the excess female births. In later years, when it was finally apparent that Mormon families were both large and evenly divided between males and females—despite behavior that should have resulted in sexual debility among the males (cf. note 10 above)—non-Mormon patent medicine entrepreneurs began marketing “Mormon” male rejuvenation preparations allegedly used by the Mormon men to protect their virility. Mormon Elders Damiana Wafers, Brigham Young Tablets and others, “in use for fifty years by the heads of the Mormon Church and their followers,” protected against “Lost Manhood, Spermatorrhea, Loss of Vital Fluids,” and other hazards.

[33] Samuel Bowles, Across the Continent: A Summer’s Journey to the Rocky Mountains . . . (Springfield, Mass.: Samuel Bowles & Co., 1865; Readex Microprint, 1966), p. 126; William Chandless, A Visit to Salt Lake . . . (New York: AMS Press, [1857] 1971), p. 208; E.H. Derby, The Overland Route to the Pacific . . . (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1869), p. 31; E.P. Hingston, ed., Artemus Ward (His Travels) Among the Mormons (London: John Camden Hotten, Picadilly, 1865), pp. xxii, 41; Bowles, Across the Continent, p. 126. Bartholow began his 1867 commentary with the observation that “in the first place there are no handsome women in Utah.”

There were many who disagreed, e.g., Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West . . . [1857], Centenary Edition (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1954), p. 254; William Hepworth Dixon, New America (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1869 [8th ed.]), pp. 131, 213; Elizabeth Wood Kane, Twelve Mormon Homes . . . (1874) (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Library, 1974), pp. 41-42.

[34] Mark Twain, Roughing It (Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Co., 1872), pp. 117-18.

[35] Bowles, Across the Continent, p. 123-24.

[36] Demas Barnes, From the Atlantic to the Pacific, Overland . . . (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1866), p. 58.

[37] Bartholow, “The Physiological Aspects . . .,” The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer 10: 197-98 (April 1867).

[38] Ibid., p. 195; The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 76:296 (2 May 1867). Bartholow attributed his information to “merchants, long residents of Salt Lake City, who had unusual opportunities for learning the facts.”

[39] Juettner, Daniel Drake, p. 261; Holland, “Memoir,” p. xliii; The Cincinnati Lancet and Observer 10:203.

[40] G.R. “The Varieties of Man,” Juvenile Instructor 3:173-74 (1868).

[41] Apostles Amasa Lyman, 5 April 1866, in Journal of Discourses [JD] 11:207; and Erastus Snow, 6 April 1880, in Conference Reports, p. 58. John Noyes’s Oneida Community advanced a related argument in support of their contemporary, partially polygamous “stirpicultural experiment.” Philip R. Wyatt, “John Humphrey Noyes and the Stirpicultural Experiment,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 31(l):55-66 (January 1976).

[42] Joseph F. Smith, 7 July 1878, in JD 20:30.

[43] JD 13:206-8 (9 October 1869).

[44] Ratios computed from male and female populations under age one, in Census Reports, 1850-1880; Dixon, New America, pp. 185-86.

[45] J.H. Beadle, Life in Utah; Or the Mysteries and Crimes of Mormonism (Philadelphia: National Publishing Co., 1870), pp. 373-74. Nearly all of Beadle’s time in Utah was spent in the non- Mormon town of Corinne. While there is probably a real basis for his somewhat overstated mortality rates, many of his related claims—as with others before him—were hearsay or demonstrably imaginative. Consider the implications, for example, of his claim to have learned “from personal observation and the testimony of many Mormons” that, as a result of polygamy, masturbation was more common among Mormon youth than anywhere else in America (p. 376).

[46] Dixon, New America, p. 187.

[47] Death rates computed from total population and death figures summarized in Census Reports, 1900, Volume IV, Population and Deaths, Table entitled “Population and Deaths, by States and Territories at each Census: 1850 to 1900.” As late as 1890, the Census Reports found Salt Lake City data insufficient to compute infant death rates. In the 1900 Census Reports, a rate of 82.9 infant deaths per 1000 births was given, about half the national average. By 1930 state-wide rates had fallen to 25 per thousand, and by 1970 to 15.

[48] Ralph T. Richards, Of Medicine, Hospitals, and Doctors (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1953), pp. 140-72. Regarding the earliest period, Richards reports a staggering overall mortality rate of 9% among Mormons during a two year period in Winter Quarters, enroute to Utah; half of the deaths were “among babies.” (p. 141)

[49] Beadle, “Life in Utah,” p. 374.

[50] “Report of Surgeon W.C. Spencer, United States Army,” in John S. Billings, War Department Surgeon General’s Office Circular No. 4, “Report on Barracks and Hospitals with Descriptions of Military Posts,” 5 December 1870 (New York: Sol Lewis, 1974), p. 366.

[51] “Report of Surgeon E.P. Vollum, USA,” in John Shaw Billings, War Department Surgeon General’s Office Circular No. 8, “Report on the Hygiene of the United States Army,” 1 May 1875 (Washington, D.C., 1875), pp. 342-43. A regimen of regular horseback riding notwithstanding, his assistant, Dr. Spencer, succumbed a few years earlier to consumption.

Despite Mormon reluctance to turn to orthodox medical practitioners, a number of “regular” physicians—both Mormon and non-Mormon—had practiced in Utah from the earliest years of the Mormon presence. While these physicians clearly had extensive exposure to Mormon “physiology,” it apparently did not strike them as worthy of a report to any contemporary medical journal.

[52] Ibid., p . 341.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] And definately not “phthisis pulmonalis” (pulmonary tuberculosis), as projected by Dr. Furley, from which Utah consistently reported among the lowest percentage deaths in the country. The categories in which Utah fared the worst were “teething” (a general term including diarrheal illnesses) and “croup.” Census Reports, 1850-1890; see also Richards, Of Medicine.

[57] Chandless, A Visit to Salt Lake, pp. 238-39.

[58] If later medical reports in support of a distinctive Mormon physiology do exist, I would be interested to learn of them. Two obvious chances to resurrect this idea were passed by almost without comment in Theodore Schroeder’s “The Sex-Determinant in Mormon Theology,” The Alienist and Neurologist 29:208-22 (May 1908) [“perhaps .. . a congenital hypertrophy of sex organs”], and “Incest in Mormonism,” The American Journal of Urology and Sexology 11:409-16 (1915) [“no claim can be made that added congenital ills will be transmitted”]. A few nonmedical sources did continue the tradition. A.E.D. De Rupert reported in Californians and Mormons (New York, 1881) that “Mormon children by the first wife are well-formed, strong and healthy; but the off-spring of wives number two, three, and four is generally feeble in body as well as in mind” (p. 161). Similarly, Smucker, in Life Among the Mormons, spoke of the “shortness of life” of the children of Utah polygamists being “proverbial,” and attributed this to “their natural imbecility from their birth, and the prevalent want of care, cleanliness, and attention” (p. 416).

More representative was the assessment of Hubert Howe Bancroft, who appears to have accepted the Mormon assertion that there was no racial deterioration “under the polygamous system.” Echoing Vollum’s impression, and anticipating later assessments, Bancroft noted that “only the better class of men, the healthy and wealthy, the strongest intellectually and physically” were polygamists,” and thus [the Mormons say], by their becoming fathers to the largest number of children, the stock is improved.” History of Utah[1890] (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), p. 384.

[59] J.E. Hickman, “The Offspring of the Mormon People,” The Journal of Heredity 15:55-68 (February 1924); Davis Bitton, “Mormon Polygamy: A Review Article,” Journal of Mormon His tory 4:102 (1977). Another related study, in 1933, is reported in Nels Anderson, Desert Saints (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1942,1966), pp. 412-13. The same general findings apply to the polygamous offspring of the Oneida community. Wyatt, “John Humphrey Noyes,” pp. 63-66.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue