Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 1

Ten Years with Dialogue: A Personal Anniversary

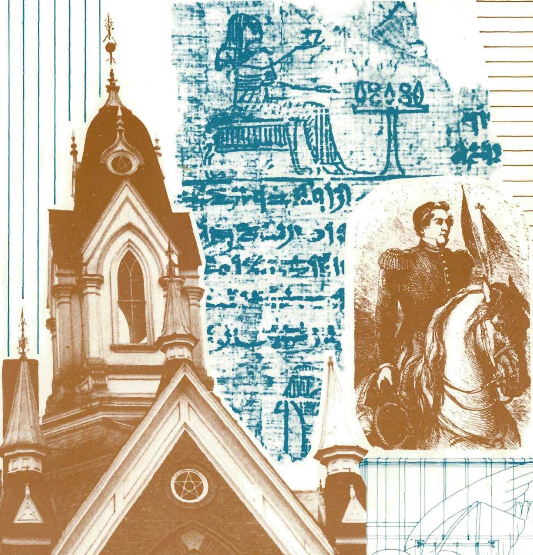

We looked a lot like the picture in the Dialogue logo, although, of course, we didn’t know it then. Gene and Charlotte England, Karl Keller and I were taking lunch on the lawn at the University of Utah back in the summer of 1957. Gene was discussing his desire to start a “scholarly Mormon journal,” not as competitor, but as complement to the church magazines, an independent journal and a much-needed outlet for Mormon writers and artists. What an exciting thought! Though I was getting married in the fall, and did not know where I would be when Gene’s dream materialized, I said, “Count me in. And wherever I am, please find me.”

Nine years later, I was found through a brochure announcing that Gene, Wesley Johnson, Paul Salisbury, Frances Menlove, Ed Geary, Richard Bushman, Diane Monsen and others were actually starting Dialogue. How can I describe my emotions? I was happily married and the mother of two and a half children, but I still longed for the intellectual excitement of my days at the “U”, for my old friends and mentors, for the Institute of Religion where I learned to love the Gospel, and for the BYU where I had enjoyed my first full-time professional appointment. That electrifying brochure brought promise of a happy, if vicarious, reunion.

And then the first issue came, thick and heavy and full of stimulating, thought provoking articles—essays that didn’t stop as soon as they got into a subject, but kept right on until either the subject or the reader was exhausted. I exhausted myself, reading into the night, even beginning to write articles and poetry of my own. Suddenly I was in touch, the Church over, with others who shared my interests. And I soon found that there were kindred souls in the Washington, D.C. area. We formed study groups, and we discussed Dialogue at firesides. Some people were shocked. One friend was so taken aback—”journal of independent thought?”—that he cancelled the subscription I had given him for Christmas. But the excitement never waned. Every issue of Dialogue sustained and excited me even when it arrived late, full of typos, or missing articles I had hoped to read (my own, for instance). And I was awed by the Dialogue editors, even though I had known some of them for years. What they were doing seemed at once heroic and a fitting expression of our Mormon heritage. I pictured handcarts, printing presses, raging mobs, pioneers, always creating “something out of nothing”—nothing, that is, except volunteer labor and faith. This was the Mormon way!

In thinking back, I believe that Dialogue’s debut was not a chance occurrence. Mormon thinkers were responding to the excitement of the sixties, but while other youth were “testing the system/’ Mormons created a constructive new outlet for individual expression. It should be noted that other groups of similar heritage responded in much the same way. Not long after Dialogue, came Courage, the RLDS journal, the Seventh Day Adventist Spectrum (almost a twin to Dialogue), and even an evangelical analogue called Sojourner. Within the Mormon community, BYU Studies was resurrected, and given a mandate to publish some things even Dialogue couldn’t touch. The time, it seemed, was right.

In Washington, our Dialogue group grew so strong that we were informally dubbed “Dialogue East” and were assigned a special issue on “Mormons and the City,” based loosely on Harvey Cox’s The Secular City, which we had studied together. Eight months later Garth Mangum, Royal Shipp and others presented Gene England with our much revised and edited offspring only to be told that we must slash articles we felt were already down to their bones. It was a useful education in the pains and plagues of editing.

In 1971 Gene and Wes announced that they were turning the editorship over to Bob Rees and moving the office to Los Angeles. Like many Dialogue stalwarts, I felt apprehensive. Dialogue was more than a member of my family; it was part of me and was not to be lightly entrusted to a stranger. Who was this Rees? Over long-distance telephone he sounded, well, long-distance. A few months later, on a trip to Los Angeles, I was finally able to meet with Bob and his staff. What a relief and a delight it was to greet each other not as ogres, but instant friends. Rees had the same nurturing openness of spirit the founding editors had.

Not long after Bob’s takeover, printing and mailing costs skyrocketed, while income stayed discouragingly stable. Even though our readership was considerably larger than other Mormon-related journals, Dialogue’s lack of institutional funding made it vulnerable to financial crisis. This crisis wearied me. I told myself that perhaps Dialogue’s time had passed. But even as I tried to imagine life without it, letters of alarm and encouragement poured in, and I became the one thing I have always avoided and abhorred—a person who asks her friends for money—a fundraiser. I wrote or called everyone I knew. Many others did the same. These efforts and the generous contributions of benefactors all over the country saved Dialogue, along with that dedicated core of readers who have stayed with us through thinning pages and thickening subscription rates.

And so Dialogue continued, even though critics, confusing the passing of novelty with an institutional graying, suggested that Dialogue “ain’t what she used to be.” To me, Dialogue was as significant and thought-provoking as ever. During the seventies, we carried fine articles on such important themes as race, sexuality, women and science—articles taking us beyond the “novelty” of the early years. And Dialogue began showing up regularly in bibliographies, histories and anthologies.

Once during a visit, Bob commented that he thought the next editor of Dialogue should be a woman. I remember thinking, “I am too old.” I was into my forties by then—well past the fomenting, fermenting years. But one midnight, in June, 1975, Bob called to say that he had served his five years and that he and his Board wanted me to be the next editor. He said that if I had matured, Dialogue had too. He thought I would love and nurture Dialogue and that my friends would help me. It took me six months to make up my mind, and another six months went by before 85 boxes of books and files were delivered to my garage, and the Dialogue secretary from California—arrived to help sort them out.

During the next few months, as the enormity of what I had done began to seep through my fitful nights and disorganized days, friends did come to help me. They seemed to appear from nowhere just when I needed them most. One saved our postal permit, another unscrambled our taxes and legal problems, while still others gave countless editing hours. We set up regular Thursday evening Dialogue nights and made big plans. We would organize according to the best management techniques: We made flow charts showing deadlines, schedules and training sessions. We debated editorial philosophy, style and direction. We even outlined grand plans for the next eight or ten issues!

Ah! the arrogance of ignorance!

Reality rapidly closed in. Subscriptions had to be rebuilt; debts had to be paid. Our professional management sessions became sorting, zipping, stuffing (envelopes and M & M’s) sessions, in which we crawled over the floor and into the night. We cut corners by setting up the office in my home, by hiring a part-time secretary, by using instant print services for mailings and by exploiting our faithful volunteers to the utmost. By year’s end, both bank account and subscriptions were in good shape.

There was only one problem: Try as we might, we had yet to bring out an issue! The Sexuality issue, which had been in utero more than three years, had been abandoned in its final hour by the L.A. printer. Despite Herculean labors on our part, it was six long months before that issue finally went into the mail. Its many crises run through my mind like a broken newsreel. Why is this so hard? I asked myself. How can so many little things add up to so many big problems?

Publishing a scholarly journal, we found, is not the heady experience it had appeared to be from afar. It is a collection of exasperating minutae which quickly becomes, in Mormon parlance, “a teaching moment” and a “learning experience.” We were learning fast, but we continued to overestimate and to underestimate. The Media issue used up an additional three months of our lives even though we had been working a whole year to “get it out early.” Then we held up the press for the Spalding article, and now we are celebrating our Anniversary issue a year late.

Oh well, we have learned that volunteer work ebbs and flows. Staffers who are fitting Dialogue into the corners and edges of their lives find that there is a time to push and a time to relax. “But, Mary,” says a friend, “some editors do get magazines out on time,” and I think to myself, “How many of them are doing it after work on Thursdays or during the baby’s naptime?”

But hope never dies. Our printer is getting used to us. By January, our curious journal will be locked into a formal production schedule, and our typeface will be on the premises (it had previously been subcontracted). Now that Dialogue is bigger (have you noticed the extra pages?), it may even become regular. Logistics and administrative prowess have never been Dialogue attractions. Our strength is in our content: essays, fiction, and poetry which “cannot be easily dislodged.” For we continue to publish a journal in which poetry is more than filler, fiction is not filed away and forgotten, facts are not filtered and readers stand firm and faithful.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue