Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 2

Needed: An LDS Philosophy of Sex

Parley P. Pratt once defined “union of the sexes” as “mutual comfort and assistance in this world of toil and sorrow.” In our day President Spencer W. Kimball has affirmed that an important function of sex is to contribute to the couple’s “becoming one.” Despite this, an LDS philosophy of sex has yet to emerge. There is a need for carefully designed research implemented in a way that will not cause offense, but which will help the Church to face critical problems as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of Church programs in solving these problems.

The gospel provides healthy and enlightening teachings about sexuality, including the belief that sex is both God-given and eternal. Gospel teachings focus directly upon interpersonal relationships. Since “sexual intercourse is among the highest expressions of these relationships, these teachings are directly applicable.

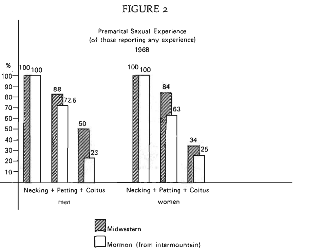

The Church strongly supports the concept of chastity and the importance of sexual fidelity, both of which firmly contribute to the success and permanence of marriage. The success of the Church’s teachings and programs in holding the line can be seen in the data presented by Wilford Smith elsewhere in this issue. It indicates that, at a time when nonmarital and extramarital sex are increasing rapidly, LDS youths have not shown a substantial increase in non-marital sexual experience.

Such courting guidelines as the Church could offer are greatly needed to help couples develop close relationships with a reasonable minimum of affectionate intimacy. When affection is so vital to marriage, it seems unreasonable simply to advise young people against kissing: the point must be made that when sexually stimulating activity dominates the relationship, other modes of sharing are crowded out. Couples can cheat themselves out of the supportive friendship so vital to marriage.

In 29 years of thinking, teaching, writing and researching on marriage and the family—the last 20 years as a faculty member of the College of Family Living at BYU—I have come to recognize that while sex is only a part of marriage, it can contribute much fulfillment and can strengthen the marriage relationship. I also am convinced that the Gospel of Jesus Christ will increase the happiness of any person who will apply its teachings, and particularly that it has much to con tribute to marital fulfillment and to the improvement of family relationships.

The responsibility for providing sex education to children within the gospel framework was specifically given to parents by President Alvin R. Dyer in his Conference Address in April, 1966. But teaching children about sex is no easy matter and many parents feel unqualified to tackle it alone. What role should the Church play in defining goals, developing materials, and providing training?

President Dyer organized a committee to write a manual on “Human Maturation.” Hundreds of hours went into the manual’s preparation. This guide— designed primarily for those who speak and write for the Church—was submitted, but has not been seen since.

Despite the Church’s shy stand on sex information for parents, I believe that Church leaders recognize the problems members are having with sexuality. Several years ago a member of the First Presidency shared with me his perception that 75 percent of the problems crossing his desk each day were sex related.

This lack of a positive focus on sex education shows up among the college students attending BYU. Approximately half of the students in my classes have had inadequate sex education, with only 10 percent indicating that their parents had explained reproduction, had communicated to them the fulfilling aspects of sexual love, or had given thoughtful reasons for refraining from premarital sex.

The students in my marriage classes are asked to prepare term papers on their reasons for refraining from premarital sex, and their strategies to prevent such involvement. About half of the students invariably reveal their vulnerability to stressful temptations in dating. The Church could do much to assist parents and teachers in giving youth thoughtful reasons for refraining and could help them develop effective strategies of sexual control.

The instructor of a BYU religion class had his students search the teachings of the “living prophets” concerning the goals of sex education. They found only one goal—chastity—which may be achieved at a cost of strong fears and negative attitudes toward sex, with such fears and attitudes causing sexual mal adjustment and dissatisfaction in marriage.

There is evidence for this in Harold Christensen’s data, reported in this issue. It appears that when LDS youth do lose their chastity, they tend to think all is lost and may therefore become promiscuous. Christ gave us the principle of repentance as a means of accepting our sinfulness in relation to his forgiving love, and it is important that we learn to use that principle in sexual matters.

The emphasis on chastity also leads some members to larger-than-life expectations about marriage. Parents and teachers often create the impression that chastity alone will guarantee a fulfilling marriage. It is not uncommon for the reality to be shocking. A philosophy of sex is needed which would help us not only to maintain chastity but to develop healthy attitudes toward sex.

The role of sex after marriage continues to pose questions for Latter-day Saints. How can sexual love be enjoyed if every encounter threatens pregnancy? It is meaningless, therefore, to talk about some of the purposes of sex as being beyond procreation unless there is freedom to use contraception.

I have noticed that students at BYU tend to be caught in a crossfire. There is active teaching of the belief that contraception is “rebellion against God and gross wickedness” and that “children are not to be delayed for social, personal, or educational reasons.” Yet there are professors, branch presidents, bishops and stake presidents who have the opposite view, suggesting to students that they give thought and attention to the matter of planning their children and spacing them through the use of medically safe contraceptive measures.

Many students feel the need to achieve a reasonably high level of professional competence and income. They face pressure to marry in order to avoid affectional intimacy during courtship and also to fulfill their responsibility to become husbands and fathers or wives and mothers. At the same time, they face financial pressure in seeking to complete their educations and to have children. The prospect of such responsibilities is overwhelming for some who would like to marry now. While there are those who manage, somehow, to work, to stay in school, get married, have a family and complete their educations, many try and then drop out. Among my vivid memories is that of a very capable pre-med student who was studying to be a physician on a scholarship. Three children in three years caused him to give up school; several years later he was still in a stop-gap job, still with three children and going nowhere in particular.

Recently a couple with a new baby—their 13th—asked: “What now? We are still very fertile, but we can’t handle anymore.” A 31-year-old woman married to a 35-year-old bishop has just had her sixth child and insists that she can never have another, yet her husband persistently believes and teaches that contraception is “gross wickedness.” How are they going to handle this conflict during their remaining child-bearing years?

A close friend’s wife, while earning the living during two of the years he worked on his doctorate, insisted that they refrain from sexual intercourse because she was afraid she would get pregnant, be unable to work, and thus cause him to drop out of school. This abstinence almost ended their marriage.

About ten years ago a senior student who had been accepted for medical school at the University of Utah talked to me about his situation. He had no outside financial support, but his fiance was a teacher in the Salt Lake schools. They felt they could make it if she could continue to work for most of his three years in medical school, but she was strongly opposed to the use of contraception. They sought counsel from a general authority who advised them that it would be the better part of wisdom to delay a family until the husband’s last year of medical school. They now have four children and are planning two more. The husband was able to obtain his medical degree and now has the earning power to support his family. In my files is a copy of a letter written in 1967 by the First Presidency to a BYU professor concerning the Church’s stand on contraception. It concludes with this statement: “. . . nevertheless, this is a personal matter left up to the couple.”

Years ago one of my friends became engaged to a young woman who worked in a general authority’s office. They asked him if he would talk to them about marriage. During the interview they asked about contraception. He answered that his conditioning was such that he could not have used any method to con trol conception, but that he fully expected his own children to. He recognized this decision as resting on culture rather than on basic religious teachings.

Because the issue of contraception is a matter that regularly comes up in our marriage classes, I developed an approach to family planning and contraception, which is summarized below:

1. The issue of family planning and the use of contraception is not a criterion for determining the worthiness of a person being considered for a position in the Church. In planning their family and spacing their children, a couple do not violate any doctrine of the Church.

2. There is not any real moral difference between a couple using the rhythm method to control conception if it works for them and another couple using contraceptive methods.

3. Conception takes place when a compatible ovum and sperm meet in the proper part of the female anatomy. One cannot make the assumption that if conception occurs, it is because God wanted it to occur.

4. People differ in their ability to manage. Some couples could manage a dozen children and others are not capable of managing two or three. The decision to have children and to space them is between the couple and the Lord; and the couple should recognize their abilities, feelings, situation and obligation to themselves and their children.

I submitted this approach to the First Counselor in the First Presidency and asked for his reaction and suggestions. In his reply he did not suggest any changes or additions.

When the issue is squarely faced, does the use of contraception to space children really violate any religious principle? Does opposition to contraception reflect a cultural position from the past? I encounter many situations where the use of birth control has contributed favorably to the husband-wife relationship, to marital satisfaction and unity, and to the mother’s body being in proper condition to carry through with the pregnancy. It is also related to the child’s receiving needed care, love and attention.

Such examples of families facing decisions, and coming to radically different interpretations of a “Church” position, only point out the need for an inte grated approach.

Several years ago, while serving as a member of a Church writing committee on a lesson manual on marriage and parenthood, I expressed the view that it was absurd to have such a manual without some lessons on the sexual aspect of marriage. The committee agreed, and assigned the lessons to me. I prepared them, using Gospel scriptures as the basis; and these lessons were presented with other lessons to two Sunday Schools in Salt Lake City. All the lessons were anonymously evaluated, with the lessons on sex receiving high marks. We sought permission from the Church Correlation Committee members in charge of the project to include the lessons on sex. They agreed, and asked that we submit the basic ideas on a tape. Four of us worked several months preparing it; we submitted it, but we have not heard of it since. The project was terminated, without explanation.

Such decisions are not necessarily being made by the general authorities in charge of the projects. In the outline for the Relief Society Manual for 1975- 1976, which was submitted to the writing committee, one lesson was to focus on sex education. A well-qualified physician wrote an excellent lesson on the topic. When the manual was submitted for approval, the lesson on sex education was removed as being unsuitable. This was done before it ever reached the general authority in charge.

Some change, however, is taking place. In the past year, an issue of the Ensign had three articles which focused on sex education and related matters. President Kimball’s statement on sex relationships was another favorable sign. It is my hope that more will come.

For family life educators, the question must be squarely faced. We have—I believe—shirked our responsibility by saying, “We can’t do anything until the Church changes its view.” This has provided a convenient excuse.

But the fact remains that, while the general authorities rightfully must shoulder the responsibility for the Church, they not only seek inspiration from God, putting themselves fully into the work, but they also search for the best thinking and writing on the subject.

On several aspects of sex, insightful writing and analysis would be warmly welcomed and accepted. For example, guidelines on conducting the affectional aspects of courtship; the best positive reasons for not participating in non-marital sex; strategies to use in the management of one’s life so that premarital sexual involvement doesn’t take place; the application of Gospel teachings and principles to the sexual aspects of marriage; careful definitions of goals of sex education, development of suitable materials; training approaches for parents: all these are needed and would be used.

Before an LDS philosophy of sex can emerge, family life educators must join with enlightened church members and their leaders in developing clear guidelines for all.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue