Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 1

A Latter-day Ode to Irrigation

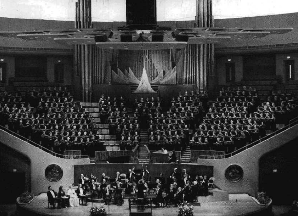

In 1907 J. J. McClellan, then organist for the Mormon Tabernacle, published a new choral suite under the extravagant title, “Ode to Irrigation.” The first of five choruses described in heavy Victorian prose a truly awesome primeval desert land scape where, “the candlesticks of the cactus flame torches here uphold,” and “bones of man and beast lie together under the miragemock of death.” After a brief blossoming under the ministrations of Pueblo Indians the land became again a Dantesque inferno until “to the throbbing of the fervent earth” the pioneers entered the scene. The composer chose a male chorus, backed by a soprano obbligato to announce that shortly after the Mormons came “green-walled thickets are choral with songs of birds,” and the once lethal desert was transformed into a “land of leafy glades.” The full chorus joined in the finale, “Glorious Land,” to be sung “With fire and patriotic fervor.”

Excesses of romantic hyperbole tend to conceal from the twentieth-century observer the core of truth which underlies this, as so much of folk literature. The land before 1847 was not as blasted as the lyricist suggested, nor as verdant thereafter. The transformation nonetheless had been dramatic. To many of those who sang “The Ode to Irrigation” in 1907 the changes they had seen meant the difference between dire necessity and comfortable plenty. With this thought in mind, we can no doubt forgive the Saints for singing such mauve poetry “With fire and patriotic fervor.”

A writer more in the modern taste, Bernard DeVoto, chose metaphors almost as strong in describing the accomplishment of his Mormon grandfather, Jonathan Dye, in cultivating the desert:

Through a dozen years of Jonathan’s journal we observe the settlers of Easton [Uinta] combining to bring water to their fields. On the bench lands above their valley, where gulches and canyons come down from the Wasatch, they made canals, which led along the hills. From the canals smaller ditches flowed down to each man’s fields, and from these ditches he must dig veins and capillaries for himself. Where the water ran, cultivation was possible; where it didn’t the sagebrush of the desert showed unbroken. Such cooperation forbade quarrels; one would as soon quarrel about the bloodstream.

Jonathan Dye’s faith, DeVoto observed, had been ” a superb instrument for the reclamation of the desert, for the creation of the West. . . . Is it clear that all this sprang from nothing at all?” DeVoto asked rhetorically.

That is the point. . . . There was here—nothing whatever. A stinking drouth, coyotes and rattlesnakes and owls, the movement of violet and silver and oliver-dun sage in white light—a dead land. But now there was a painted frame house under shade trees, fields leached of alkali, the blue flowers of alfalfa, flowing water, grain, gardens, orchards. . . . This in what had been a dead land.

Such warm praise, coming from a confirmed iconoclast who had been unsparing in his criticism of other aspects of Mormon society, would seem to have put the final seal of approval upon the Mormons’ achievement in western agriculture. The resourcefulness of the Mormons in wresting abundance from the most forbidding wastelands has taken its place among the legends of American folklore. It has become a popular cliche that the Mormon pioneers made the desert blossom as the rose.

Obscured by the cliche, however, is a record of remarkable innovation and achievement in American agriculture. Common sense would prompt the Mormon pioneers to bring water to withering crops, but the development of irrigated agriculture on a regional basis involved problems of monumental scale and complexity. It was necessary to build an extensive network of dams, reservoirs, canals and ditches with only the crudest surveying instruments and without the aid of heavy machinery. Entirely new social institutions for building and maintaining the system and for apportioning the water equitably had to be developed. Once the delivery system was built the skills and techniques of applying water effectively to extensive fields had to be developed. Only those who have been confronted by a charging stream of water in midfield, armed with nothing but gum boots and an Ames shovel, and have attempted to make the stream lie down placidly and evenly over the dry surface, can fully appreciate what the Mormon pioneers had to learn.

I was recently reminded of how much I have forgotten from my youth on a family farm in Idaho. My father was able to work such wizardry with the water that he irrigated a ten acre beet field uphill for twenty years and never knew the difference. I assumed that such talents, after several generations of irrigation experience, had become permanently incorporated into the family’s genetic code. Last summer when the soil in our small backyard garden in Salt Lake City appeared too dry for the germination of seeds I determined for the first time in many years to try my hand at irrigation. I carefully dug a head ditch and drain ditch at either end of the plot and scratched a grid of furrows between them, each furrow equidistant on either side from the rows of seeds I had planted. I then confidently turned a full hose of water into one corner of the grid, expecting that I could sit down comfort ably into a lawn chair and watch the stream course through the system and saturate the waiting seeds.

After about fifteen minutes I found I had created an impressive mud puddle in that one corner of the garden, but the water stubbornly refused to venture into the inviting ditches and furrows. I then moved the hose from what I had intended to be the head ditch to the drain ditch. This worked better, but the water still flowed only into the first furrow and only about halfway. In the meantime the soil was melting like sugar and the whole system seemed in imminent danger of being washed out. Somewhat embarrassed, I accepted the advice of a neighbor and placed small rocks at the foot (now the head) of the furrows to regulate the flow into each. I finally got a respectable thread of water entering into the first four of the furrows in the plot and feeling that the most painful part of my re-education in agronomic arts was over I sat back to watch the water seep through the soil until it saturated the seeds.

It was then that I discovered how different Utah soil is from Idaho soil. First it became obvious that a rise in the center of the plot was keeping the water from getting past the middle of each furrow. But the blocked moisture did not seep laterally to the parched seed as it would have done on the farm in Idaho. It percolated straight down into the light soil for an hour and a half and never progressed horizontally more than an inch in either direction. The radish and spinach seeds seemed forever safe from inundation by this particular irrigation system.

Finally, I disconsolately admitted that my genetic endowment was less than I had imagined, attached a sprinkler to the hose, placed it squarely in the middle of the plot and successfully completed my task. Wiping the sweat from my brow, I was suddenly struck by the fact that in those few moments I had learned better than through days of reading old documents how brilliant had been the accomplishment of farmers who in 1847 began settlement of the arid Intermountain West. I quietly added my own, less florid, ode to that McClellan had written in 1907.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue