Articles/Essays – Volume 07, No. 4

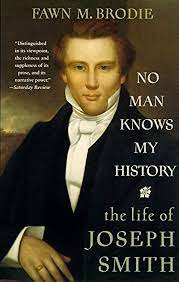

Brodie Revisited: A Reappraisal | Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet

For more than a quarter century Fawn Brodie’s No Man Knows My History has been recognized by most professional American historians as the standard work on the life of Joseph Smith and perhaps the most important single work on early Mormonism. At the same time the work has had tremendous influence upon informed Mormon thinking, as shown by the fact that whole issues of B.Y.U. Studies and Dialogue have been devoted to considering questions on the life of the Mormon prophet raised by Brodie. There is evidence that her book has had strong negative impact on popular Mormon thought as well, since to this day in certain circles in Utah to acknowledge that one has “read Fawn Brodie” is to create doubts as to one’s loyalty to the Church. A book which continues to have this much influence warrants the second edition which Alfred A. Knopf published in 1971.

But how good a biography is No Man Knows My History? That, of course, is the central issue between those who praise and those who condemn the work. Both Mormon and non-Mormon scholars seem to agree that that substantially depends upon another question—is what Fawn Brodie said about Joseph Smith true? On that I should like to venture some “informed” opinions based upon heavy reading of the scholarly works in the field and also what Herbert O. Brayer in an early review of Brodie said would be a prerequisite for any “definitive” life of Joseph Smith—intensive study of the sources, especially those in the historian’s archives in Salt Lake City.

Let me emphasize before doing this that I wish to consider Brodie’s interpretation of Joseph Smith and early Mormonism on her own secular terms. Nothing which I suggest below is intended to render any final resolution to the question which I think she mistakenly tries to answer—is Joseph Smith a prophet of God in the sense that the Church he founded maintains, in an ultimate or cosmic sense? I do not believe that question can be finally answered by historians who deal with human artifacts left from a hundred and forty years ago. The historian has no sources written with the finger of God to prove that Joseph Smith was called to his divine mission, nor does he have any human sources to prove conclusively that he was not. One’s answers to this cosmic question depend entirely upon the assumptions he brings to it—assumptions about the nature of the world and man’s place in it; these rest in the last analysis upon personal predilection, not historical evidence. Leaving the larger question aside, for purposes of discussion I choose to meet Brodie on her own grounds. With the naturalistic assumptions of the professional historian, I wish to evaluate some of the implications of her book which require close scrutiny.

If one reviews the vast amount of scholarship in Mormon history since 1945 and uses this as a criteria for evaluating Brodie’s book, it seems undeniable that much of her history retains its relevance and authenticity. Some of the issues which she raised she succeeded in settling with a finality which seems remarkable. Thus in 1945 the Spaulding theory of the origin of the Book of Mormon was still strongly in vogue, most scholarly works accepting it as the explanation of the origin of the Book of Mormon. Following her trenchant attack on the theory its popularity quickly declined. Today nobody gives it credence. It was Brodie who insisted that Joseph Smith, not Sidney Rigdon, was the dominant personality in early Mormonism, that the ideas and institutions which gave Mormonism its unique qualities were largely his. Some of Rigdon’s letters recently discovered confirm his subordination to Smith. Brodie argued that Joseph Smith, despite his lack of formal education, was a man with rich imagination and high intelligence who responded to the intellectual currents of his time from which he drew elements which shaped Mormon thought. Today many Mormon scholars tend to accept this view, differing with her only on the extent of Joseph’s dependence on environmental forces.

The Joseph Smith depicted by Brodie was essentially a rational human being who worked his way through his problems with understanding and foresight, but certainly not omniscience. When one recalls what I. Wood bridge Riley had maintained—that Joseph Smith was an epileptic and the Book of Mormon the product of his physiological fits—or what Bernard DeVoto said as late as 1930—that Joseph was a paranoid whose major works were the result of his madness—one can appreciate how much the general conception of Joseph Smith in academic circles has been altered for the better.

Critics of Brodie forget too easily that she actually read and took seriously the anti-Mormon newspapers and thereby saw the importance of the Kingdom of God in stirring anti-Mormon animosity in Illinois. She recognized how the collective power of the Mormon community made enemies of those who would not have been so on purely religious grounds. Among her insights was the recognition that the prophet made more than a few enemies by attempting to extract concessions from both political parties while giving his full allegiance to neither.

At a time when Mormon writers were inclined to consider only the cosmic implications of the prophet’s work, or like John Henry Evans to exaggerate his significance in the context of American history, and when non-Mormons like Beardsley heaped scorn upon him and belittled him, Brodie focused upon his human qualities, his loves, his hates, his fears, his hopes and ambitions. She helped many Mormons to recall that the prophet had a human side and that not all of what he did was done in the name of the Lord nor with transcendental significance.

In other areas, in her scepticism regarding the reality of the first vision, her arguments favoring Joseph’s authorship of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham, and her handling of polygamy, her views are still debated and remain to some degree unsettled. Reverend Wesley Walters continues to maintain that the first vision was a myth while many Mormons maintain its historicity. Today not so much attention is paid to her contention that View of the Hebrews provided the main source for the Book of Mormon, but that the issue is at the moment quiescent does not mean that it will remain so. Overshadowing it is the conflict over the Book of Abraham, which since the rediscovery of some of the papyri which Joseph Smith claimed to translate has made that work central in the evaluation of Joseph Smith as translator. Whatever one makes of these issues, Brodie’s relevance clearly remains.

Thus it should be evident that Brodie has written an immensely important book, a powerful book, which greatly influenced the thinking of Mormon liberals and conservatives with respect to the life of the prophet. If it continues to be read and have the impact it has had then its greatness will be undeniable. I am inclined to think, however, that it falls short of greatness because of fundamental weaknesses which no amount of patching in a later edition can correct. Since, if anything, the supplement magnifies those weaknesses, it may well become an epitaph written by Fawn Brodie on her own book. She acknowledges in the supplement,

One of the major original premises of this biography was that Joseph Smith’s assumption of the role of a religious prophet was an evolutionary process, that he began as a bucolic scryer, using the primitive techniques of the folklore of magic common to his area, most of which he discarded as he evolved into a preacher-prophet. There seemed to be good evidence that when he chose to write of this evolution in his History of the Church he distorted the past in the interest of promoting his public image. . . . There was evidence even to stimulate doubt of the authenticity of the ‘first vision’ which Joseph declared in his official history had occurred in 1820 when he was fourteen.

I would agree that this is one of her major premises, perhaps even her controlling premise. It influences her handling of the first vision, gold digging, Joseph’s theology and plural marriage. It also leads directly to the assertion in her supplement that “here are evidences not only of unbridled fantasy but also of contrivance and seeming fraud” (p. 412). The Joseph Smith she depicts is a deliberate deceiver who played out his masquerade for personal advantage. The implication is that Joseph Smith was in fact sceptical as to the truths of Christianity, that he never underwent that moment of conversion which he details in his autobiography, and that he continued to enact his subterfuge until for so doing he was shot by a mob at the Carthage jail. She maintains that, to a considerable extent, his religious efforts were play-acting for the benefit of an appreciative audience.

Brodie sensed some difficulty in this argument, for she said in her original edition that early in Joseph’s career he “reached an inner equilibrium that permitted him to pursue his career with a highly compensated but nevertheless very real sincerity” (p. 85). She admitted that by 1832 Joseph played his religious role persistently and “did not relax from his role even before his wife” (p. 123). From this point in her work Brodie says little about the rationalizations Joseph would have had to go through where his religious role was imposed upon him. She even fails to mention it again at the time of the martyrdom, perhaps itself an admission that even the early Fawn Brodie saw difficulties in supposing that such a man could go through all the adverse situations Smith was put to and yet maintain his masquerade. By deft phrasing, by saying that early he reached an “equilibrium,” Brodie avoided the difficult point of telling us what the nature of his inner reconciliation was.

Thus, at its core, the biography is external only. Brodie was never able to take us inside the mind of the prophet, to understand how he thought and why. A reason for that may be that the sources she would have had to use were Joseph’s religious writings, and her Smith was supposed to be irreligious. It is indeed a major weakness of her work that by her very assumptions she cannot get back into Joseph Smith’s nineteenth century world, which was so religious in its orientation. She cannot handle the religious mysticism of the man or of the age because there is too much of modern science in her make-up, too much of Sigmund Freud, too much rationalism. For Brodie to believe in the reality of another world, a world of the spirit, seems incredible. Possibly it was because she was a Mormon, proud, in her own way, of her people and their heritage. Faced in the 193O’s and 1940’s with a general cynicism toward religion among many intellectuals, she may have been anxious to destroy the image of Mormonism that saw it as something to be sneered or laughed at. Such concerns may have caused Brodie to over-stress the prophet’s rationality, play down his mysticism, and dismiss his religious thought, which was perhaps embarrassing, as a “patchwork of ideas and rituals.”

It may be that Brodie erred initially when she accepted the prevailing view of the 1930’s that the American Revolution was a period of indifference or even hostility toward religion, reflected in the attack on the established churches and the resulting separation of church and state. She says that Joseph Smith Sr. “reflected that irreligion which had permeated the Revolution, which had made the federal government completely secular.” While a recent scholar terms the Revolutionary era one of religious “desuetude,” no one today would call it irreligious. Even the Deists acknowledged the existence of God and a prevailing morality in the universe, holding that, by studying nature, man could learn more about God than from the Scriptures. Theirs was an attack on some traditional Christian views but not on religion. Separation of church and state resulted from a union between the Jeffersonians and the pietistic sects who sought to make religion a matter of choice, not legal necessity. But even Jefferson would agree that religious faith was necessary for the stability of the social order. The Baptists, Presbyterians and Methodists who supported him were intent not upon the destruction of religious influence, but upon making their own sects more influential. There were few Americans at the end of the eighteenth century who could justly be called irreligious. Certainly, we shall see, neither Asael Smith nor Joseph Smith Sr. were among them.

In her supplement Brodie contends that new available sources on Joseph Smith do not demand any major revision of her interpretation (p. xi). I would challenge this. There are in the Church archives hundreds of manuscripts by or about Joseph Smith which Brodie did not see and which are now generally available to scholars. In none that I have examined is there a hint that Smith thought of himself in any other terms except those manifest in his published writings—that he was a man called of God to lead a movement and start a church. When one has read through and noted carefully this vast miscellany of material, it becomes impossible to believe Brodie’s original thesis. Joseph Smith played out his role not only before his wife and all his friends every minute of every day, of which we have record, beginning in 1829, but also in the few personal diaries which he wrote himself. In one of these, written in 1832, Joseph records the following:

O may God grant that I may be directed in all my thoughts. O bless thy servant. Amen.

Another entry, for 1833, is revealing:

In the morning at 4 o’clock i was awoke by Brother Davis knocking at my door saying: Brother Joseph come get up and see the signs in the heavens, and I arose and beheld to my great joy the stars fall from heaven; yea, they fell like hail stones, a literal fulfillment of the word of God as recorded in the holy scriptures and a sure sign that the coming of Christ is close at hand. O how marvellous are thy works O Lord and I thank thee for thy mercy unto me thy servant. O Lord save me in thy kingdom for Christ sake. Amen.

One reason that Brodie concluded that Joseph had veiled his personality behind a “perpetual flow of words” in his history may be that she assumed he had actually dictated most of it. We now know that large portions of that history were not dictated but were written by scribes and later transferred into the first person to read as though the words were Joseph’s. That fact makes what few things Joseph Smith wrote himself of great significance. These confirm that during his most intimate personal moments he thought about the same things he spoke of publicly—his relationship to God and his calling as the religious leader of his people. Even with regard to plural marriage, where Brodie is so confident that the real Joseph Smith, the pleasure lover and sensualist, shows through, there is no evidence in his writings to suggest that he thought of it in other than religious terms. Had Brodie seen more of what is in the archives she might have hesitated before adopting her thesis of intentional fraud.

Seer Stones and Money Digging

What were the evidences of fraud she thought she saw? Setting aside her basic cynicism about religious matters and her contempt of polygamy, her argument rested on several dubious assumptions. First was her acceptance of the validity of the testimony collected by Philastus Hurlbut that before Joseph Smith was a prophet he was an irreligious money digger who used a magic stone to discover buried treasure. Her thesis is that Joseph gradually matured as a prophet, gave up his stone and presumably his belief in magic, and gave himself wholly to acting out the more dignified religious role. There is, of course, a major discrepancy in the argument because Joseph did not give up the stone or cease to believe in its powers even after he had reached the pinnacle of his power in Nauvoo. Brigham Young records that in late December, 1841, Joseph told the Twelve Apostles “that every man who lived on earth was entitled to a seer stone, and should have one, but they are kept from them in consequence of their wickedness, and most of those who do find one make evil use of it.” Young added casually, “He showed us his seer stone.”

Her use of Hurlbut’s sources must now be seriously questioned. Richard Anderson has shown that very similar or even identical phrases show up repeatedly in the testimony of these witnesses, phrases like “acquainted with the Smith family,” or “addicted to vicious habits,” which demonstrate Hurlbut’s (or E. D. Howe’s) heavy hand in the composition of the testimonies. Since we know that Hurlbut went back to Palmyra purposefully to find evidence against Joseph Smith,[1] Anderson’s findings confirm what should have been suspected all along, that they were at best highly colored and at worst deliberately misrepresentative accounts. We get some idea of the difference with which a more friendly interviewer could have handled such testimony by comparing the Hurlbut interviews with those of W. H. Kelley. Kelley, a Reorganized Mormon, in 1867 questioned some of the same families as Hurlbut but got some very different responses. The witnesses under Kelley’s scrutiny were much less likely to say that they knew a story to be fact, more likely to admit that they had merely heard it. Often they confessed that they had no first hand information. They did not seem to think that Joseph or the Smith family were particularly bad. Kelley’s interviewing was not necessarily more impartial than that of Hurlbut. One can find examples of repetitious phrasing in Kelley’s testimonies too, but it demonstrates the great influence that a biased interviewer could have. It seems credulous on Brodie’s part to believe the statement of Willard Chase (p. 38) that Joseph “told one of my neighbors that he had not got any such book [of plates], nor never had such an one,” or Peter Ingersoll that “he told me he had no such book, and believed there never was any such book” (p. 37) when the phrasing is so similar, and when the statement by Chase came from a third unidentified source. It is essentially upon evidence like this that Brodie depends to prove her case of Smith’s early cynicism and fraudulent intentions.

There may be little doubt now, as I have indicated elsewhere, that Joseph Smith was brought to trial in 1826 on a charge, not exactly clear, associated with money digging. However, the reports of what was said at that trial are contradictory. One version says that Joseph Smith Sr. and his son “were mortified that this wonderful power [of the younger Smith] which God has so miraculously given . . . should be used only in search of filthy lucre.” This points up a major discrepancy in Brodie’s interpretation. Her thesis that the prophet grew from necromancer to prophet assumes that the two were mutually exclusive, that if Smith were a money digger he could not have been religiously sincere. This does not necessarily follow. Many believers, active in their churches, were money diggers in New England and western New York in this period. Few contemporaries regard these money diggers as irreligious, only implying so if their religious views seemed too radical. The historian of Middletown, Vermont, Barnes Frisbie, was much closer to the truth when he said that the rodsmen who flourished in Orange County, at Wells, Middletown and Poultney, Vermont at the turn of the nineteenth century were accentuated by religious not monetary motives. They saw themselves as the children of Israel and believed in impending judgments, in the restoration of primitive Christianity and in the healing gifts.

Frisbie’s characterization of these rodsmen is substantiated by Ovid Miner, who wrote about them in the Vermont American, May 7, 1828.

About 1800 one or two families in Rutland county, who had been considered respectable, and who had been Baptists, pretended to have been informed by the Almighty that they were the descendents of the Ancient Jews, and were, with their connexions, to be put in possession of the land for some miles around; the way for which was to be providentially prepared by the destruction of their fellow townsmen. [They claimed] power to cure disease, and intuitive knowledge of lost or stolen goods, and ability to discover hidden treasures.

Frisbie insisted that Oliver Cowdery’s father was a member of this group. Despite some similarity between the ideas of the rodsmen and those later advocated by Joseph Smith, and despite the fact that when Oliver Cowdery took up his duties as a scribe for Joseph Smith in 1829 he had a rod in his possession which Joseph Smith sanctioned, there is no evidence as yet to prove a direct influence. Rather, what this suggests is that Brodie’s dichotomy between money digger and prophet rests upon her twentieth century assumptions. Only if she were, in fact, looking at the matter cosmically, from the standpoint of Mormon theology, would her conclusion make sense. Then, of course, she might ask, what is Joseph Smith, prophet of the Lord, doing with a seer stone and hunting treasure with it? For the historian interested in Joseph Smith the man, it does not seem incongruous for him to have hunted for treasure with a seer stone and then to use it with full faith to receive revelations from the Lord. In short, there was an element of mysticism in Joseph and the early Mormons that Brodie did not face up to. Some of the rodsmen or money diggers who moved into Mormonism were Oliver Cowdery, Martin Harris, Orrin P. Rockwell, Joseph and Newel Knight, and Josiah Stowell. There is evidence for most of them that their interest in Mormonism was essentially religious. If they had religious motives, why couldn’t Joseph Smith?

In the 1830’s most Mormons did not consider Joseph’s use of the seer stone inconsistent or embarrassing. David Whitmer actually considered its use the mark of a true prophet, and only after Joseph began to receive revelations without it in hand did Whitmer suspect that the young prophet had fallen from the faith. Whitmer believed that Joseph manifested genuine humility and sincerity in his earliest years and only later, after he came under Rigdon’s influence and began to gain economic and political power, did he show signs of worldliness. If this be so, it contradicts directly Brodie’s thesis, for she has Joseph’s evolution the other way around.

The First Vision

Brodie’s assumption of a deceitful prophet was supported by her discovery that early Mormons did not relate the first vision story consistently, and, as she maintained in 1945, the earliest version by the prophet was not written until 1838. She has had to revise the argument somewhat since it is now known that the earliest account extant was written in 1832. But there are, undeniably, differences in the several accounts, not all of them minor from the standpoint of Mormon theology. These contradictions, Brodie still insists, add up to deception.

Again, it is difficult to follow the logic of her reasoning; nor is her approach consistent. I cannot tell whether her chief purpose in handling the first vision the way she does is to understand the human being named Joseph Smith or to discredit his theology and thus his Church. It is difficult to tell whether Brodie is the mature historian probing and searching to find the essence of the early movement and Joseph Smith’s part in it or a disgruntled ex-Mormon striking back at a “myth” told her in her childhood.

Despite Brodie’s observations, there is a basic consistency in the several versions of the first vision. In each of them Joseph maintains that he was disturbed by the many arguments going on around him about religion and the various claims to exclusive truth made by the several denominations. In all but one, the first, he indicates that it was a religious revival which spurred him to inquire of the Lord in prayer. He says in the manuscript of the 1838 version that it had never occurred to him until his vision that all the churches might be wrong. Later perhaps he may have marked this out, for it did not appear in the published account. In the manuscript of 1832 he says he “became convicted of my sins” and began comparing the teachings of the churches with those of the Bible. In the several versions he maintains consistently that after his conversion he had a period of backsliding and that he was again brought back to his mission by another vision, this time of an angel. To focus upon the discrepancies touching the personages of the Godhead in the first vision story, whether one or two personages, is to concentrate on a theological question and to miss its historical significance. The crux of Smith’s account, as Mario DePillis has suggested, is his detestation of the confusion which sectarian conflict engendered in his mind. After undergoing a con version experience, and after other circumstances brought him to the necessity, he began a movement with certain striking characteristics, perhaps the central feature of which was its totality, its anti-pluralistic social and political institutions which excluded all secularism.

By setting up the Kingdom of God Joseph Smith acted upon his central insight, that religious contention was wrong, demoralizing and debilitating of religious faith, and that it was his job to restore the ancient Christian faith that would unite the pure in heart in a community with a prophet at its head—a community where all who would could live in peace and await the millennial reign of Christ. Brodie and others have been preoccupied with the first vision’s theological implications which were the product of Joseph Smith’s and the Mormon people’s later thinking. This has caused them to miss the important implications as to the social and religious origins of Mormonism which may be the essential point. If over the years Joseph’s conception of the Godhead changed, this is not evidence of fraud any more than the adaptation of other aspects of his theology in later years proves to be. One has to begin with very rigid, even absolutistic assumptions about his prophetic role before such a claim has consistency.

There has been some doubt whether a revival could have taken place in 1820. Milton Backman and others have provided evidence to show that a revival, indeed many of them, did occur in that “region of country” (to use the Prophet’s phrase) around Palmyra in 1819 or 1820. Joseph Smith used the same phrase later in his history to designate the whole area along the Mississippi occupied by the Mormons, including parts of Iowa. Charles G. Finney used it also, to include all of western New York. There is no reason to doubt that it was meant to encompass a large area. There remains the argument of Wesley Walters that the revival must have come in 1823 or 1824 since, according to William Smith, both Reverends Stockton and Lane participated, and they were both in Palmyra only for a few weeks during the 1823-24 revival. It seems likely, however, that William’s belated recollections on this point are erroneous. Contrary to Walters, he is the only witness who insists that Lane and Stockton were involved. William was young at the time, from nine to thirteen, depending on the date one chooses for the revival, and according to his own admission, did not pay much attention to religious matters since he had not yet sown his “wild oats.” In a much earlier account than the one in question, William said that a “Reverend M ” was the minister who converted Joseph. If William is not clear on this point then we cannot give his unsubstantiated claim about Stockton credence. That Joseph and Oliver Cowdery show some uncertainty about the prophet’s age when he had his vision does not prove that he did not have the conversion experience he describes, but only that dates were not so important to him as the experience itself. Had it come, as Walters assumed, in late 1823 or early 1824, right after Alvin’s death, it might not have been so difficult to place exactly. If it came earlier, then it may be that Joseph felt some guilt about his backsliding so that it was painful to him to remember how early his conversion actually did occur.

Brodie made much of the point that with Joseph dreams quickly became visions. She quotes Lehi in the Book of Mormon, “behold I have had a dream, or in other words I have seen a vision” as evidence that Smith was given to fantasy and could not always tell the difference between dreams and reality. The question which Brodie fails to consider is whether most Mormons in this period did not in fact equate the two, whether this was not a cultural condition rather than a psychological one. Not having the benefit of Sigmund Freud’s analysis of dreams, the early Mormons, like many others of the time, were inclined to think that their dreams had cosmic significance. In the 1832 manuscript Joseph says the coming of the angel caused him to be “exceedingly frightened I supposed it had been a dream or vision but when I considered I knew that it was not.” If he were the deceiver Brodie supposes, it is unlikely he would have equated these terms so frankly in his manuscript and in the Book of Mormon. That Joseph believed that dreams or mental images were visions, that he also believed that what he felt intuitively was the voice of the Lord speaking within, was not inconsistent with his background and with the time and place in which he lived. Mario DePillis argues that Mormon visions came during periods of great stress and offered surcease from trouble some doubts. If this proves to be true for other Mormons it may also be true for Joseph Smith and offers an antidote to Brodie’s simplistic view that his visions were fraudulent.

The candid way that the Mormon prophet in the Doctrine and Covenants describes the mental effort that went into his own revelations long ago impressed Edward Meyer, a student of early Christianity, that he was no deceiver. The prophet told Oliver Cowdery, who attempted unsuccessfully to translate part of the Book of Mormon:

Behold you have not understood. You have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought, save it was to ask me; but . . . you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it be right, I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you.

Smith’s candor is shown again in his manuscript history where he admits he was tempted to seek financial gain from the plates. His temptation to seek profits does not prove his irreligion but his financial need. Whatever the nature of the inner turmoil he experienced at this time, there is no reason to doubt the outcome he describes—that his sense of religious mission proved more powerful than his impecunity.

The Smith Family and Joseph’s Calling

In her supplement Brodie raises the question whether Joseph’s family believed in his visions. Since his mother and brother Samuel remained on the rolls of the Presbyterian Church until 1830 and were apparently active until mid-1828, they must not have taken his visions seriously. As a matter of fact, an unpublished biographical account of Samuel Smith indicates that he had to be urged to join the Mormon movement in 1829. It informs us that Joseph

labored to persuade him concerning the gospel of Jesus Christ which was now to be revealed in its fulness; Samuel was not however, very easily persuaded of these things, but after much inquiry and explanation he retired in order that by secret and fervent prayer he might obtain from the Lord wisdom.

There is no mention of any doubt that Samuel is supposed to have had about his brother’s integrity but only that he required explanation and waited for personal conviction. It provides evidence that there was no collusion within the Smith family, for Joseph had to persuade each member individually. Those, like Samuel, already committed to Presbyterianism did not give up their commitments easily.

Joseph Sr. had already separated himself from the existing churches, con vinced that they were apostate, and was looking for the true one. When Lucy and Samuel joined the Presbyterians about the time of Alvin’s death, the elder Smith would not, since the Presbyterian minister who preached his son’s funeral said Alvin was going to hell. Joseph Sr., like his father Asael, both of whom Brodie badly misrepresents in her efforts to make the family seem indifferent to religion, had been a Universalist but drifted out of that movement. Like thousands following the religious upheavals of the Revolutionary period, the elder Smith had become a seeker. What he wanted in his church was the right balance of rationalism and spirituality, visions and the gifts of healing. When his son told him that he had been called to restore such a church, he quickly identified with the movement.

Lucy, on the other hand, had spent long years in search of a church that met her emotional and social needs, and was from all appearances satisfied with the Presbyterian congregation in Palmyra. She was reluctant at first to give it up. It was her son, not she, who had the early vision and then went about his worldly ways. If, even after the second vision, Lucy did not hasten to follow her son’s leadership, this only proves that she was a very determined person who was not easily moved from the course she had chosen. Lucy does not say whether Joseph said anything to her about his vision. Joseph only says that he told her he now knew that Presbyterianism was not true. But in any case, when Joseph began to translate the Book of Mormon and thus provided concrete evidence of his prophetic calling, Lucy and Samuel too paid heed. Why would they have left the Presbyterians at all if they doubted the truth of Joseph’s visions?

In searching through hundreds of letters written by various members of the Smith family, I have found only two who expressed any doubt of the story told by Joseph. One of these was Mary B. Smith Norman, apostate daughter of Samuel, who was disillusioned about plural marriage. She wrote in 1908 that she was not sure that Joseph had all the inspiration claimed for him when he “wrote the Book of Mormon.” The other was vitriolic uncle Jesse Smith, who had no first hand information but in 1829 wrote to Joseph Sr. that he had heard that the golden plates had been fabricated out of lead. In none of the letters written by William Smith (and there are many in the Strang Papers at Yale and at Salt Lake City) is there any indication that he questioned Joseph’s account of his early revelations or of the translation of the golden plates.

Joseph’s Revisions of His Story

But what of Joseph’s careful scrutiny and revision of his history from time to time and the frequent changing of his revelations? Brodie assumes that these too are evidences of deliberate deceit (pp. 21, 141, 289). Joseph Smith did manifest the usual human concern for putting himself and his work in the best possible light, but it seems doubtful that on the whole he sought to mis represent or bury his past. If so, he went about it in strange ways. He never made any effort to destroy the old versions of his history or his revelations, and he kept far too many records if he had any idea that he would deceive his followers or some day fool his biographer. As has already been pointed out, that history is unusually candid at many critical points. Joseph Smith admitted, for example, that he had been a gold digger, but, quite naturally, played down its significance in his early career since the fact was used by his enemies to discredit him. With respect to the revision of his revelations, it may be that like most Americans and most Mormons, Joseph cared much more for the present than he did for the past, that he was more anxious that the revelation express today’s inspiration than that his infallibility as a prophet be maintained. Joseph did have some concern for updating his revelations, keeping those parts that were still relevant, revising them where necessary to meet the current situation. He did this with respect to both organizational and doctrinal matters. But this may only suggest that he did not worship his words, that he was confident of the inspiration flowing into him, that he had an urgency to put down his new insights and get them applied in the Church. He did not seem to be overly bothered by the fact that his revelations needed revision. Unless we assume that Smith was something of a fool, which Brodie seems unwilling to maintain, then it is difficult to believe that he was so short sighted that he would revise his revelations and not try to destroy the old ones. It must be that he had other purposes besides deception in mind.

The Witnesses to The Book of Mormon

What of the prophet’s story about gold plates, and what about his witnesses? Given Brodie’s assumptions, was there not deception here, if not collusion? Brodie maintains that the Prophet exercised some mysterious influence upon the witnesses which caused them to see the plates, thus making Joseph Smith once more the perpetrator of a religious fraud. The evidence is extremely contradictory in this area, but there is a possibility that the three witnesses saw the plates in vision only, for Stephen Burnett in a letter written in 1838, a few weeks after the event, described Martin Harris’ testimony to this effect:

When I came to hear Martin Harris state in public that he never saw the plates with his natural eyes only in vision or imagination, neither Oliver nor David . . . the last pedestal gave way, in my view our foundations.

Burnett reported Harris saying that he had “hefted the plates repeatedly in a box with only a tablecloth or handkerchief over them, but he never saw them only as he saw a city through a mountain.” Nonetheless, Harris said he believed the Book of Mormon to be true. In the revelation given the three witnesses before they viewed the plates they were told, “it is by your faith that you shall view them” and “ye shall testify that you have seen them, even as my servant Joseph Smith Jr. has seen them, for it is by my power that he has seen them.” There is testimony from several independent interviewers, all non-Mormon, that Martin Harris and David Whitmer said they saw the plates with their “spiritual eyes” only. Among others, A. Metcalf and John Gilbert, as well as Reuben P. Harmon and Jesse Townsend, gave testimonies to this effect. This is contradicted, however, by statements like that of David Whitmer in the Saints Herald in 1882, “these hands handled the plates, these eyes saw the angel.” But Z. H. Gurley elicited from Whitmer a not so positive response to the question, “did you touch them?” His answer was, “We did not touch nor handle the plates.” Asked about the table on which the plates rested, Whitmer replied, “the table had the appearance of literal wood as shown in the visions of the glory of God.” It does not seem likely from all of this that Joseph Smith had to put undue pressure on the three witnesses. More likely their vision grew out of their own emotional and psychological needs. Men like Cowdery and David Whitmer were too tough minded to be easily pres sured by Smith.

So far as the eight witnesses go, William Smith said his father never saw the plates except under a frock. And Stephen Burnett quotes Martin Harris that “the eight witnesses never saw them & hesitated to sign that instrument [their testimony published in the Book of Mormon] for that reason, but were persuaded to do it.” Yet John Whitmer told Wilhelm Poulson of Ovid, Idaho, in 1878 that he saw the plates when they were not covered, and he turned the leaves. Hiram Page, another of the eight witnesses, left his peculiar testimony in a letter in the Ensign of Liberty in 1848:

As to the Book of Mormon, it would be doing injustice to myself and to the work of God of the last days, to say that I could know a thing to be true in 1830, and know the same thing to be false in 1847. To say my mind was so treacherous that I have forgotten what I saw, to say that a man of Joseph’s ability, who at that time did not know how to pronounce the word Nephi, could write a book of six hundred pages, as correct as the Book of Mormon without supernatural power. And to say that those holy Angels who came and showed themselves to me as I was walking through the field, to confirm me in the work of the Lord of the last days—three of whom came to me afterwards and sang an hymn in their own pure language; yes, it would be treating the God of heaven with contempt, to deny these testimonies.

With only a veiled reference to “what I saw,” Page does not say he saw the plates but that angels confirmed him in his faith. Neither does he say that any coercion was placed upon him to secure his testimony. Despite Page’s inconsistencies, it is difficult to know what to make of Harris’ affirmation that the eight saw no plates in the face of John Whitmer’s testimony. The original testimony of these eight men in the Book of Mormon reads somewhat ambiguously, not making clear whether they handled the plates or the “leaves” of the translated manuscript. Thus there are some puzzling aspects to the testimonies of the witnesses. If Burnett’s statement is given credence it would appear that Joseph Smith extorted a deceptive testimony from the eight witnesses. But why should John Whitmer and Hiram Page adhere to Mormon ism and the Book of Mormon so long if they only gave their testimony reluctantly? It may be that like the three witnesses they expressed a genuine religious conviction. The particulars may not have seemed as important as the ultimate truth of the work.

To raise doubts about the validity of some of Brodie’s arguments is not to dismiss her book. Her biography will continue to have great influence upon professional historians until someone writes one with equal or greater plausibility. With the benefit of new sources and better insight into the intellectual and cultural background of early Mormonism, this may be possible. It is not enough to write reviews or articles for learned journals, for these are read by few, nor to publish volumes of new sources for these provide no substitute. Those who attempt a biography must write with courage, for no matter what they say many will disagree strongly. And they must write with insight and power, for one of Brodie’s strengths is that her book is exciting reading. Above all, in the face of contradictory sources and world views, they must strive to tell the truth. It may do well to recall John Garraty’s warning that “the average man is so contradictory and complicated that by selecting evidence carefully, a biographer can ‘prove’ that his subject is almost anything.” To write the truth about a man who was so many sided, so controversial as Joseph Smith is a very difficult thing. Nonetheless, with an attitude less cynical than Fawn Brodie’s, it is time for some of us to try.

No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet. By Fawn M. Brodie. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971. 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, xvi + 499 + xxii pp.

[1] [Editor’s Note: This footnote is an asterisk in the PDF] As admitted by E. D. Howe to Arthur Deming in 1885. See the Arthur Deming Papers in the Mormon Collection at the Chicago Historical Society. Anderson’s citation of the Painesville Telegraph, January 31, 1834, misrepresents what is admitted there.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue