Articles/Essays – Volume 07, No. 1

The Discomforter: Some Personal Memories of Joseph Fielding Smith

I was about twelve when I first met President and Sister Smith. They had come to visit the Thirty-Third Ward, Bonneville Stake, and the family of my pal, Doug Myers, my bishop’s son and President Smith’s grandson. I had been impressed with Doug’s overwhelming respect for his grandfather, a respect which often arose in our tentative youthful probings of the mystical and mysterious in gospel doctrine. I recall how impressed Doug had been by his parent’s admonition that his behavior would reflect, for good or evil, upon the name of his great-great-grandfather, Hyrum, and his grandfather, then the President of the Council of the Twelve, and I had observed at several points how this filial piety made Doug hesitate in engaging in some of the marginal activities of Scout-aged boys.

My own awe for President Smith increased as I studied the gospel, and I grudgingly concluded, time and again, that the President seemed to know what he was writing or speaking about, despite the fact that he had the audacity to make me very uncomfortable in the conclusions he reached. Somehow it is much easier to read of Alma’s ripping from his contemporaries the guises and shams which prevented them from achieving harmony with their God than it is to have men of President Smith’s stature doing the same thing to us—and I have occasionally caught myself making reactionary statements which, when deliberated on in private, sound shockingly like the self-justifications of the men of Ammonihah—and I am again made uncomfortable. President Smith was, I have concluded, a great Discomforter.

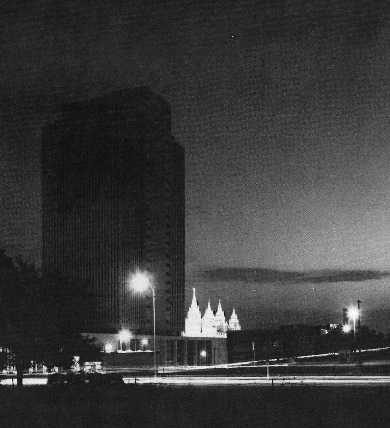

The President continued to make me uncomfortable throughout my young life, but I recognized even then that it was a kind of divinely appointed dis comfort, a rather unwelcome stirring to righteousness. After our first meeting I became much aware of his ministry. I recall hearing him in various conferences of the Stake and Church; I recall watching him skip vigorously up and down the steps of the Church Office Building, where my mother was employed; I recall looking up suddenly in Deseret Book Co. and seeing him standing across from me, thumbing a book—an electric experience heightened by his nod and soft smile, a smile which seemed at odds with the firmness and sternness which I had come to associate with this Discomforter.

The stern image I originally had of him was finally shattered for me one morning in Luzerne, Switzerland, in 1958. A number of us Elders in the Zurich District had gathered in the L.D.S. chapel that spring morning ai a missionary conference. Exhilarated by the beauty of the city, by the spirit of the conference, and by the bouyant assurance that we were engaged in a good work, we sat, self-satisfied, in the conference that freshly green spring morning. Suddenly the rear door of the chapel swung open and the President and Sister Jesse Evans, his delightful wife, entered and began shaking hands with each of us. None of us had been aware of President Smith’s presence in Europe, and it seemed to us that morning, isolated as we were in a small branch house in Europe, and steeped as we were in awe for the General Authorities, as if a messenger of God had suddenly dropped in from the realms of glory.

As the President began to speak to us that day, I, and I’m certain the rest shared my feelings, came to realize what it really meant to be a Special Witness for Jesus Christ. I felt my earlier judgments shaken as, quietly and fervently, the President began to recount the events leading to the crucificxtion of Jesus—certainly not a new story to any of us. Yet this time there was something different—a current of electricity vibrated in the air, a feeling so intense that I began to think that this time the story would end differently—that Jesus would miraculously free himself and call down the wrath of heaven upon the insolent mortals.

The story did not change, and President Smith, as he led us breathlessly through the streets of Jerusalem, became visibly moved, his voice growing less and less controlled. Suddenly he was describing brilliantly yet softly the love which God has for His Only Begotten, and the immense woe which must have swept His Being when He saw His Only Begotten slain by other, weaker, yet still beloved creations. “It makes me wonder,” he whispered. Then President Smith paused; he wept.

My eyes blurred, but I sensed the emotion ripple across the soul of every person in that room. It was a solemn and sweet moment. A powerful witness came to me that this gray-haired, dignified old man with clear eye and firm voice was in fact an apostle of that Man-God who died on Calvary. It was a sobering realization, and I am refreshed, even now, by the sensation of peace which its recollection brings to my soul. For the first time President Smith became a Comforter to me.

Not long after this experience, I concluded my mission and returned to the world—to materialistic, comfortable Salt Lake City—there to confront, among other experiences, my destiny with the Utah National Guard. While serving in the Guard, I was assigned to escort President and Sister Smith to Camp Williams, where the President was to address the 142nd Military Intelligence Company, a unit comprised almost wholly of returned missionaries who had learned a foreign tongue. There were some exceptions; that is, two of the few non-Mormons in the unit were a Major and a Lieutenant, both members of the Greek Orthodox faith, fine men and true. It was, ironically, these two who were assigned the responsibility of arranging the church program for the L.D.S. group. So the two gentile officers, wary of confronting the President without a saintly buffer, asked me, a very non-commissioned officer, to accompany them in escorting President and Sister Smith to the camp. From the moment we picked the couple up at their home on South Temple Street until we were far out Redwood Road, Sister Smith, with great charm and humor amused us with tales of the couple’s narrow scrape with fate in 1939, when President and Sister Smith were sent to conduct the recall from the European missions of all the missionaries imperiled by Hitler’s Wehrmacht. After chatting for some time, I realized that the two officers, seated in front, had not been sufficiently drawn into the conversation. Hoping to bridge any conversational gap, I turned to the President and informed him, in a bumbling attempt at tact, that the two officers were members of the Greek Orthodox faith.

They were fateful words. President Smith’s body immediately tensed; he sat forward, a gleam in his eye and a new vigor in his face; he saw his calling vividly. Clearing his throat, he said, “I’m sorry to hear that, for they worship a false God!” In the midst of our stunned silence, he took charge, complimented the officers on being believers and evidently fine men, but he reiterated that the God which they worshipped in the Greek Orthodox faith was not, unfortunately, the true and living God, and he bore witness to the truths embodied in Mormonism concerning the nature of the Father. He carefully explained to them, between Bennion and Camp Williams, the difference between the true God and the teachings of the apostate churches concerning God.

I was bemused; I was uncomfortable. On the one hand, I was amazed and full of admiration at President Smith’s firm stand and eagerness to be a missionary; on the other hand the worldly man in me fretted about the reaction of the two officers, for President Smith was explaining, clearly and fervently, with no apologies, the very lesson on the Godhead which I had given so many times in Austria and Switzerland. Still, despite my concern for the officers’ sensitivities, I found myself fascinated by the simplicity and the depth of the truth he was expounding, and by his wholehearted devotion to his missionary calling.

After we had escorted the President and his wife to the meeting place in the Officer’s Club at Camp Williams, I cornered the two officers and asked them what they had thought of their first meeting with President Smith. Unlike President Smith, / half-apologized to them for his proselytizing. I was relieved and chagrined at their answer: Relieved because they spoke of him with greatest affection and admiration. “He did his duty,” smiled one of them, and the other added lightly that both of them were married to Mormon women and had thus been thoroughly exposed to Mormonism, stake missionaries, and the intensity of our missionary commitment, and they would therefore have been surprised had President Smith not taken the opportunity to preach Mormon doctrine. I was then chagrined that I had been so hesitant to give my entire support to President Smith as he undertook to do in Utah what I had just spent nearly three years trying to do for the people of Austria and Switzerland. He had again aroused in me that familiar old feeling of divine discomfort.

Now the great Discomforter has gone, and we who are made of less celestial stuff are left to reflect on the rich gifts which President Joseph Fielding Smith brought to the Church and the world. I am amazed at the variety of those gifts; but his greatest single gift may well be his Alma-like example of perfect integrity and steadfastness in bearing fearless witness to the power of Jesus in changing lives—in being a kind of divinely appointed Discomforter to all of us, gentile and saint alike. I’ll miss him.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue