Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 1

Excerpt from Eleusis: The Long and Winding Road, Translated and introduced by James Goldberg.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. Also, as of now, footnotes are not available for the online version. For citational and biographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided below the web copy and on JSTOR.

Introduction

In 2014, R. de la Lanza spent his morning commute feverishly writing. All through the long bus ride from his home in the southern part of Mexico City to his work at a university in the famed Roma neighborhood, he poured out a story that had been forming in his head for five years, he says, “like clouds gathering for the storm.”

And what a storm! Eleusis ranks among the most ambitious novels in Mormon literary history. Weaving together the tales of two multigenerational sets of Mormon characters, the novel embraces the grand sweep of Mexico’s Mormon history. There’s a cameo by Melitón González Trejo, a depiction of the divisions around the schismatic Third Convention, friendships formed at the Benemérito academy. Through it all, de la Lanza shows a consistent interest in both the earthy, messy realities of his characters’ lives and the spiritual longings that pull at them, no matter how they may drift from their principles. The novel’s name, a reference to the ancient Greek Eleusinian Mysteries, promises a sacred story of descent and ascent. With the help of classical and scriptural allusions, R. de la Lanza keeps that promise, inviting us to take a look at the long and winding road through mortality to transcendence.

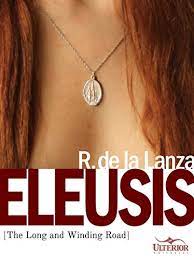

Writers who choose to depict Mormon experience all face fraught rhetorical and aesthetic decisions about how to navigate the minefield of Mormon audience sensibilities about profanity, sexuality, and anxieties about how we’re depicted. The cover to Eleusis, a Young Women medallion over a woman’s bare chest, makes clear that de la Lanza’s novel follows the approach of David Farragut’s famous naval order: “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” There is plenty of sex, much of it desperate and lonely, some of it spiritually significant. As far as concern for how Mormon characters are depicted, the novel is unflinching. While aware that stigmatized minority groups may have reason to be concerned about what other people will think of them based on fictional depictions, de la Lanza resolved to “tell sincere and brutally truthful stories, even if they hurt.”

The result is a wild ride through the heights and depths of Mormon life, an invitation to look closely through our inevitable moments of ugliness to find a deeper beauty. In this issue of Dialogue, we present you with a translation of the novel’s first two chapters to give you a taste of this exceptional literary work.

CHAPTER 1

We are divided beings. That is the great diagnosis of our existence. Above the vastness of our being hangs the power of Hephaestus’s ax, poised to strike open the head of Zeus with a fateful blow—born either of supernal will or infernal caprice. This truth is at the root of the myth Plato placed (with a touch of acid humor) in the mouth of Aristophanes to explain our search for love: man and woman were once a single being but were divided by gods who envied the completeness of their joy. This separation probably began, to be sure, with a slight division, like the first hint of cleavage between a young woman’s budding breasts—yet ended up becoming as definitive as the severing of a cord at birth that makes a son no longer one with his mother. A brutal and profound incision is precisely the displaced and confusing state which is the sum of humanity: between oneness and multiplicity, between integrity and partition. It is the low plain between potential and action, adventure and nostalgia, past and future, entity and essence, ego and id, space and time, life and death, time and eternity. Between spirit and matter.

The only salvation from that topographic hell is the aching hope for a gathering of separated fragments, a restoration of oneness, a healing of the fracture. We must repair or replace ligaments to bind together a shattered whole. This re-linking of lost pieces is at the etymological root of what we call religion. Re-ligion, from the Latin ligare, is to help lost pieces find a connection, hook up, cleave together.

When he’d finished drafting dialogue for Aristophanes, Plato cast himself as the speaker to share another origin story for humankind. He said our souls are separated from the Supreme Soul and imprisoned in the body. And the only release from that captivity is death. But when we die, Plato said, our soul splits from the body to re-link itself to the God from whom we were sundered.

The Christian tradition followed Plato in this way of explaining the re-linking (the re-ligion) of the divided man to God, though leaving man still as a spirit, irrevocably separated from his material corporality to gain eternal union with the Father God.

Yet how should one definitive division save us from another existential separation? Perhaps the fundamental division of a human being, reflected even in the division of the brain into hemispheres, cannot be put to an end simply by asserting we should remain split from something we once had, be it Plato’s ideal love, Epicurus’s intellectual pleasure, or the physicality of our own flesh and blood.

Luz María, Moroni’s grandmother, was a simple Spanish teacher in a rural secondary school who lived divided, in addition to all else, even between the phonological and semantic levels of words. From the time she was a child she couldn’t stop thinking about the fact that cima and sima, whose sound was identical, meant things as different as top and bottom, summit and abyss. The division in which she lived became a bleeding wound when, from the height of her idyllic union with Antonio, her husband, she fell to the depth of widowhood and the orphaning of her two children.

Antonio was ten years older than Luz María, who had seen just seventeen springs when he began courting her. He was a charismatic taxi driver who dedicated his free time to singing ballads on a local radio program in the state capital: their courtship commenced at the precise moment when the radio waves lifted Antonio’s voice out, dedicating a song “to Señorita Luz María, sister of Mr. Rafael, the primary school principal.”

That afternoon, Luz María waited in the window for Antonio to come by. When he arrived, her brother the principal answered the door. The two men talked and after a few minutes that felt to Luz María like hours, Principal Rafael called to her. She had permission to go out to the park for an hour with Antonio.

Antonio and Luz María connected. They felt that connection like a myth of god-envied love. Like the root meaning of the word religion.

In less than a year, they got married. Only civilly, because the parish where Antonio’s baptismal record was kept had been expropriated by the government and sold to a bank, causing his documents to be lost in the transfer to the archdiocese’s headquarters. Even the couple’s union, then, was suspended over the division between civil and ecclesiastical sanction—not that Luz María cared much, as she was Catholic in name only. That is to say: she was Catholic not by devotion but by a momentum that was already beginning to wane. Six of her eight brothers had decided to join an evangelical sect, holding Protestantism to be, in Rafael’s own words, “a more enlightened movement than tyrannical Catholicism.” None of them made much fuss about missing the chance to see their sister show off her simple, impeccably white dress at the altar of the state cathedral: the steps of city hall, surrounded by merchants, social workers, and police, were enough.

Although Luz María and Antonio wanted them from the beginning, it took three years for the children to arrive. First Esteban and two years later Esther, Moroni’s mother. In many ways, Luz María was a woman envied by others. Antonio was very popular for his songs, a cheerful man with twinkling eyes who made good company.

That camaraderie took him one day to march alongside students protesting in solidarity with tenants of the state capital’s markets against the governor’s voracious appetite for taxes. The protestors included Antonio, as an unofficial public figure, in the march’s vanguard line, carrying the banner with their slogans. But when they arrived at the governor’s house, an army squad charged the protestors, firing on them and brandishing bayonets. Screams filled the air, the cacophony of violence flooded the streets with its deafening roar.

Luz Maria, Moroni’s grandmother, had begged Antonio not to go. But just like Hector refused to yield to his wife Andromache and her prophetic words about the son he would leave orphaned, so Antonio placed his honor before all else. A high and tragic sense of honor that now cost him a confrontation, man to man, with a diminutive soldier who sank his bayonet into Antonio’s belly and, holding him fast with the blade, fired his rifle.

That afternoon only two people died: Antonio and the “Chente” Mandujano, a union leader for the School of Science and Arts. They were buried with honors, and the mob of their mourners caused such a riot that the governor fled as soon as he was notified that the President of the Republic was on his way to the state to find out in person what had happened. But just as Andromache knew that the glory of the hero is never enough to shelter his family, Luz María’s fate was hardly better than that suffered by the guileless Trojan princess with the snow-white arms. Rafael secured Luz María a place as a Spanish teacher in a high school on the outskirts of the city, although she had to attend her brother’s school in the afternoon to study spelling, grammar, and literature while breastfeeding Esther and raising Esteban as much as possible.

It was in those lessons that she returned to the problem of cima and sima, the shared sound signifying summit and abyss, which without her knowledge had been the landscape of her life’s tragedy.

Luz María, Moroni’s grandmother, never resigned herself to the topographic hell of her division. After listening time and time again to the sympathetic cliché that Antonio’s death had been God’s will, she assumed the infantile attitude of official antagonism toward Him. But after long weeks of draining rancor, she realized that perhaps only God would be the answer: His will could not be so terrible. So she learned to hate Him with love. But the only way to search for Him was the Church. At least the paraphernalia, the imagery, and the solemn theatricality of the parishes had more effect than the austere rational examination of Protestantism in her soul, which hungered for some impression so strong that it would grant her escape from her horrifically sundered reality.

She read the Bible five times from cover to cover without understanding one jot. The only lingering impression came from the passage where a dead man, thrown almost carelessly into the ground, came back to life because he had fallen beside the grave of the prophet Elisha, which was linked in her mind to the sentence from the apostle Paul who dictated that, although the letter of the law kills, the spirit gives life. Inspired by the deepest tenderness for Antonio, she finally raised the massive sacred tome in a deranged frenzy and declared there must be more than this, there must be another book apart from this insufficient piece.

As she sought a revelation or reconnection, she turned to a medium to talk with Antonio and confirm his promises of love. “If he still exists,” she thought, “surely he still loves me.” But the medium, a flaccid and foul-smelling gitana who had once been in love with the troubadour taxi driver, could never make contact with him, much less communicate anything to his young widow.

But one day Luz María ran into two foreign youngsters in the street. They were very tall, with intensely yellow hair, light eyes of a color between gray and blue, and pink skin lacerated by the sun. They were dressed in white shirts and ties. Each one carried a simple black briefcase, and although one of them seemed barely able to think in a broken Spanish complete with foreign accent and alien grammar, the other had mastered even the local idioms. They said they were missionaries and that they wanted to talk to her about a book of sacred writing, complementary to the Bible.

Holy Scripture, until now incomplete, divided, was whole once again.

When Mormon missionaries taught Luz María that the resurrection, that is to say the re-union of her deceased husband Antonio’s immortal spirit with his material body, would be definitive and final and that the same would happen to her, she felt an uncontrollable force that burned in her chest and at the same time brought tranquility to her mind. And when they related how, through ceremonies whose hopeful promise exceeded their exceptional nature, she could not only see him again but continue to be his wife and preserve their children as offspring forever, she felt in her whole being, without knowing if it was in her spirit or in her body or in both an indescribable peace that made her leave, once and for all, the spiritualism sessions in which she had tried to contact Antonio with the intention of knowing if he continued to exist on any plane of reality.

She was at last able to visualize salvation from the chasm between the sound and the sense of the word religion.

CHAPTER 2

He woke up to the sound of the phone ringing. He was so tired—even though he felt the impulse to answer, he didn’t have the strength. Two more rings. Niza stretched out her arm over him and picked up the receiver.

“Hello? . . . Yes, one moment,” she said into the phone. Then to him: “It’s for you.”

Moroni half-opened his eyes, frowning. He stuck the receiver to his cheek and cleared his throat without getting out of bed.

“Yes . . . How?” He fell silent for a long time. “OK, sister. Thank you.”

He hung up. He lay there with his eyes wide open, staring at the phone. He knew it wouldn’t be the last call that night and wished with all his might that he didn’t give a crap.

“Sister? Weren’t you an only child?” Niza started stroking him, trying to get him to turn over.

He was almost naked. The dark gray briefs that had made him feel so free now accentuated his sense of lack and orphanhood. He thought of his garments—the undergarments he had stopped wearing years ago, despite their sacred meaning. He missed them. All at once, the caress bothered him: it seemed to him that it was becoming obscene.

“I need to go.”

“At this hour?”

“I have to leave.”

Niza returned to her dream and Moroni got up.

All his impulses were amplified. From a hidden case, he frantically pulled out a long white pair of boxers, then a T-shirt that completed the set. They smelled of dust. Rushing like a schoolboy, he went straight into the shower and let the first stream of cold water fall on his head until the shower reached its usual warmth. He washed himself thoroughly, as if wanting to remove scents tattooed all over his skin. He wished he didn’t have to carry the weight of his life—and decided that the most legitimate feeling he could hold onto to grapple with it would be an intention to immediately remove Niza from his life: scream her out of bed and kick her out of his apartment in a luxury of violence, fueled by convulsive moral indignation.

But she was not to blame, when all was said and done. He had met her by fortunate coincidence, like his last three romantic partners. Romantic partners? What did that even mean? They weren’t girlfriends. They weren’t friends, either. Come on, they weren’t even lovers, that was a word full of adventure, of cynical joy. Even “romantic partner” was off: it felt like just another euphemism to refer to the merely carnal. But in this case, it was not only carnal. There was a story. There were hours of conversation and mutual exchange, fertilizing the tensions that relaxed at night.

He devoted himself to reliving the vague moment when he decided that he would play the game Niza proposed—as if by doing so, he could purge himself of it. He found that he had entered the dynamic out of sheer boredom. Because his loneliness was weighing on him. Because he worried that people believed his isolation was a reflection of some perversion. He could not afford that social risk. While he didn’t mind admitting to his associates and employees that Sandra had asked for a divorce, it was only because broken families are the most common thing in our world. Even among Church members. So “he who is without sin . . .”

But what the hell did it matter to the brothers and sisters if, since Sandra left, he moved further and further away from them? He laughed at himself and was filled with a self-inflicted reproach for not being able to fulfill his intentions to be strong, come out afloat, and demonstrate to his daughter, to God, and to himself that he would overcome adversity. And that he was better than many of those who pointed at him then, including Lenin, who—apparently unsatisfied with condemning him to the outer darkness with his petulant preaching—now came out on a whim to interrupt Moroni’s first deep sleep in years: in the middle of an unexpected night of drunkenness, and in which he had just had almost two hours of passionate intimacy.

Moroni put on his white underwear, mumbling what little he remembered from the explanations given about its symbols. A musty scent of long storage still clung to them. For a moment, he thought that if he inhaled deeply enough to sigh, the dust from his garments would make him cough, so he held in his breath until it caused a yawn, accompanied by a gasp that almost sounded like a death rattle.

Wedged in between deodorants and sunscreens, there was an old bottle of Eternity For Men. He sprayed under and over his clothes, and the pungent sweetness not only covered the scent he had wanted to tear off his skin in the shower and the smell of dust, but also helped convince him that if he saw Sandra, she would recognize the fragrance of their first date.

From the next room, Niza followed him closely with her ears. He had been sleeping in the apartment for a couple of weeks. He clearly didn’t live there, though: in the closet there was only one change of his clothes and shoes. They arrived together at night, after dinner, dancing, or fighting, and as soon as they crossed the threshold of the apartment, they ritually repeated what had happened the first time. An awkward silence enveloped them. They avoided the drawn-out process of sitting down, talking, and seducing each other: as if fleeing the living room, they took refuge in the bedroom with the speed and seriousness of a child sent to bed without supper. Between nervous smiles, they undressed and caressed each other feverishly before joining awkwardly in an unsavory paroxysm worthy of two stupid teenagers who believe that this feeling of doing everything wrong is a sign of doing things right. During the plateau of their trance, they pretended with screams and moans to achieve a peak of pleasure—which did really come, but in such an uncertain way that neither of them dared to ask or claim or apologize for anything. To her, he was a tender, soft, delicate, almost childish lover incapable of hurting her. So she was perfectly willing to forgive him for his low energy.

He was always very tired. And it was true. The only thing that made him respond was knowing that, if he failed to, the massive humiliation would be a mark on his forehead that he could never erase, just like the aromas that were tattooed on his skin and that he had to disguise with the scent of Eternity.

The phone rang again. He ran into the living room to pick up the extension so Niza wouldn’t bother answering. He raised the receiver to his ear without saying anything. After two seconds of waiting, he heard a “Hey? Is that you?”

He didn’t respond at all.

“I guess they already told you.”

More silence.

“I only wanted to know if you’re OK.”

Obstinate silence.

“Well, that was all . . . Bye.”

It was his daughter’s voice. Not the one he’d expected.

He put on an elegant white shirt without ironing it, a black sweater, and an Oxford gray suit with a fashionable cut that accentuated the width of his back and seemed to inflate his chest. From the tie rack, he took an old and bland tie. He hadn’t worn it for more than fifteen years, but he never thought about taking it down to put it in a box of mementos, let alone of throwing it away. It was sacred, almost an amulet. As he tied the knot, he was surprised to find that it smelled not of dust but of memories.

Almost automatically, he poured himself a cup of coffee to wake up. But when he raised the cup to drink it, he saw himself reflected in the dark, trembling mirror in his white shirt, suit, and tie, and the vision caused him a sudden, startling fright, like the shock of finding a spider in folded clothes.

He took the car keys and yanked the door closed. It was still very dark outside.

•

CAPÍTULO 1

Somos seres escindidos. Ése es el gran diagnóstico de nuestra existencia. Sobre la vastedad de nuestro ser se cierne el poderoso e inminente golpe de hacha con que Hefesto partió la cabeza de Zeus, como una fatídica voluntad superna o como infernal capricho. Ya Platón ponía en boca de Aristófanes la etiología, no carente de humor ácido, de nuestra búsqueda amorosa: hombre y mujer habrían sido en algún momento un solo ser, dividido por los dioses por envidiar su gozo pleno. Esa separación pudo comenzar, cierto es, con una leve hendidura, como la que cursa a la mitad de un joven pecho femenino, y terminó siendo tan definitiva como la de un hijo que, tras nacer, no vuelve más a ser uno con su madre. Una brutal y profunda escisión es precisamente el extraviado y confuso estado que sume a la humanidad entre la unicidad y la multiplicidad, entre la integridad y la partición. Es la baja planicie entre la potencia y el acto, entre la aventura y la nostalgia, entre el pasado y el futuro, entre la entidad y la esencia, entre el ego y el id, entre el espacio y el tiempo, entre la vida y la muerte, entre el tiempo y la eternidad. En fin, entre el espíritu y la materia.

De ese infierno topográfico la única salvación es la añorada posibilidad de reunir las partes separadas, de restaurar su unicidad, de sanar su fractura, de restablecer sus ligamentos o, por lo menos, suplantarlos. Ligar, pues, los fragmentos, para que no se pierdan el uno al otro. Ligarlos una y otra vez. Ligarlos y re-ligarlos.

Según el mismo Platón, nuestra alma está separada del Alma Suprema y aprisionada en nuestro cuerpo. La única forma de que obtenga su libertad es la muerte. Pero al morir, nuestra alma se escinde del cuerpo para re-ligarse al Dios del cual se desprendió en un principio.

La tradición cristiana siguió a Platón en esta forma de explicar la re-ligión del hombre escindido de Dios, pero dejándolo todavía en calidad de espíritu, separado de su corporalidad material para siempre, aunque unido eternamente al Dios Padre.

¿Cómo es que un desprendimiento definitivo nos salva de otra separación? Quizás la limitada mente escindida del ser humano, reflejo de la naturaleza escindida en los dos hemisferios del cerebro, no termina por admitir que debamos permanecer escindidos de algo que ya hemos tenido, como el amor ideal, el placer intelectual y, mucho menos, de nuestro cuerpo.

Luz María, la abuela de Moroni, era una sencilla maestra de Español en una secundaria rural que vivía escindida, además, entre el plano fonológico y el semántico de las palabras. Desde que era niña no terminaba de conciliar el hecho de que cima y sima, cuyo sonido era idéntico, significaran cosas tan diversas como cumbre y abismo, respectivamente. La escisión en la que vivía se volvió una herida sangrante cuando, de la cima de su unión idílica con Antonio, su esposo, cayó hasta la sima de la viudez y la orfandad de sus dos hijos.

Antonio era diez años mayor que Luz María, quien contaba diecisiete abriles cuando él comenzó a cortejarla. Era un carismático taxista que dedicaba sus ratos de ocio a cantar baladas en un programa de la radio local, en la capital del estado. El cortejo comenzó, precisamente, con un mensaje por radio en el que Antonio dedicó una canción “a la señorita Luz María, hermana de don Rafael, el director de la escuela primaria”.

Esa tarde, Luz María esperó en la ventana a que pasara Antonio. Cuando llegó, don Rafael salió a la puerta, ambos hablaron un momento, y al cabo de unos minutos que a Luz María le parecieron horas, el profesor don Rafael llamó a Luz María. Tenía permiso de salir una hora al parque con Antonio.

Antonio estaba ligando con Luz María.

En menos de un año se casaron. Sólo por lo civil, porque la parroquia donde se guardaba la fe de bautismo de Antonio había sido expropiada por el gobierno para venderla a un banco, y sus documentos se extraviaron en el traslado a la sede del arzobispado. La pareja quedó, pues, unida, pero la unión misma quedó suspendida sobre la escisión que media entre la sanción civil y la eclesiástica, aunque aparentemente a Luz María no le importara gran cosa, pues se decía católica. En realidad no era tan devota, sólo mustia. Seis de sus ocho hermanos habían decidido seguir una secta evangélica por aquello de ser el protestantismo “un movimiento más ilustrado que el tiránico catolicismo”, a decir del propio don Rafael. Nadie hizo mucho aspaviento por no ver a su hermana presumir su sencillo vestido, impecablemente blanco, en el altar de la catedral del estado, sino sólo a la entrada del palacio municipal, entre marchantes, limosneros y gendarmes.

Aunque los deseaban desde el principio, los hijos llegaron tres años después. Primero Esteban y dos años después Esther, la madre de Moroni. En cierto modo, Luz María era una mujer envidiada por las demás. Antonio era muy popular por sus canciones, de ojo alegre y muy buen compañero.

Esa camaradería lo llevó un día a marchar junto a los estudiantes que apoyaban las protestas de los locatarios de los mercados de la capital del estado, contra la voracidad tributaria del gobernador. Lo incluyeron, como una figura pública no oficial, en la línea de vanguardia, cargando la manta de las consignas. Al llegar a casa del gobernador, un escuadrón del ejército se abalanzó sobre el contingente, disparando y blandiendo las bayonetas. El griterío, con todo y que era generalizado, parecía un ruido ensordecido por las mismas calles.

Luz María, la abuela de Moroni, le había rogado a Antonio no ir. Pero, tal como Héctor no cedió ante Andrómaca ni por las proféticas palabras sobre el hijo que habría de quedar huérfano, así Antonio antepuso el honor ante todo. Un elevado y trágico sentido del honor que ahora le costaba su enfrentamiento cuerpo a cuerpo con un menguado soldado que le hundió la bayoneta en el vientre y, teniéndolo sujeto de esa forma, disparó el fusil.

Aquella tarde sólo murieron dos personas: Antonio y el “Chente” Mandujano, un líder sindical de la Escuela de Ciencias y Artes. Se les sepultó con honores y la turba hizo tales destrozos que el gobernador se dio a la fuga en cuanto recibió la notificación de que el Presidente de la República estaba en camino al estado para enterarse en persona de lo acontecido. Pero, tal como Andrómaca sabía que la gloria del héroe nunca basta para cobijar a su familia, la suerte de Luz María fue apenas mejor que la sufrida por la hermosa princesa troyana de los cándidos brazos. Don Rafael le consiguió a Luz María una plaza como maestra de español en una secundaria de las afueras de la ciudad, aunque ella tuvo que asistir a la escuela normal por las tardes y aprender con su propio hermano ortografía, gramática y literatura, mientras amamantaba a Esther y criaba a Esteban como podía.

Fue en esas lecciones donde volvió a disertar para sí misma el problema de la cima y la sima, que, sin que ella lo supiera, no era otra cosa que la geología de su peripecia trágica.

Luz María, la abuela de Moroni, nunca se resignó al infierno topográfico de su escisión. A fuerza de escuchar tantas veces que la muerte de Antonio había sido la voluntad de Dios, asumió la actitud infantil de enemistarse oficialmente con Él. Pero tras largas semanas de desgastante rencor, supo que quizás sólo Dios sería la respuesta: Su voluntad no podía ser tan mala. Así, aprendió a odiarlo con amor. Pero la única forma de buscarlo era la iglesia. Al menos la parafernalia, la imaginería y la grave teatralidad de las parroquias surtían más efecto que el austero examen racional del protestantismo en su alma hambrienta de alguna impresión tan fuerte que le hiciera evadirse de su horrorosa realidad escindida.

Leyó la Biblia cinco veces de cabo a rabo, sin entender ni jota. Sólo la impresionó el pasaje en el que un hombre muerto, arrojado casi sin cuidado a tierra, volvió a la vida por haber caído cerca del sepulcro del profeta Eliseo, y lo enlazaba con la sentencia del apóstol Pablo que dicta que, aunque la letra de la ley mata, el espíritu vivifica. Inspiró en Don Antonio la más honda ternura, y la consideró desquiciada, cuando levantó el mamotreto sagrado y solemnemente declaró que debía existir otro libro aparte de ése, que era insuficiente.

En su forma particular de religarlo todo, buscó a una médium para hablar con Antonio y refrendarle sus promesas de amor: “Si sigue existiendo, tiene que seguir amándome”. La médium, una gitana flácida y apestosa, que en otras épocas había estado enamorada del taxista trovador, nunca pudo hacer contacto con él, ni mucho menos para comunicarlo con su joven viuda.

Pero un día Luz María se topó en la calle con dos jovenzuelos extranjeros. Eran muy altos, de cabellos intensamente amarillos, ojos claros entre el gris y el azul y una rosada piel, lacerada por el sol. Vestían camisas blancas y corbata. Cargaban cada uno un maletín sencillo y negro, y aunque uno de ellos parecía apenas rumiar un español despedazado por la gramática ajena y el acento foráneo, el otro parecía dominar incluso los modismos locales. Dijeron ser misioneros y que querían hablar con ella de un libro de escritura sagrada, complementario de la Biblia.

La Sagrada Escritura, hasta ahora incompleta, dividida, estaba junta otra vez.

Cuando los misioneros mormones le enseñaron a Luz María que la resurrección, es decir la reunión del espíritu inmortal de Antonio, su esposo fallecido, con su cuerpo material sería definitiva y que lo mismo pasaría con ella, sintió una fuerza incontrolable que ardía en su pecho y al mismo tiempo tranquilizaba su mente. Y cuando le contaron que, mediante unas ceremonias cuya esperanzadora promesa sobrepujaba su rara naturaleza, podría no sólo volverlo a ver, sino continuar siendo ella su consorte, y preservar a sus hijos como hijos eternamente, sintió en todo su ser, sin saber si era en su espíritu o en su cuerpo, o en ambos, una paz indescriptible que la hizo dejar, de una vez por todas, las sesiones de espiritismo en las que había intentado contactar a Antonio con la intención de saber si él seguía existiendo en algún plano de la realidad.

Pudo al fin visualizarse salvando el abismo que hay entre el plano fonológico y el semántico de la palabra religión.

CAPÍTULO 2

Lo despertó el teléfono. Estaba tan cansado que a pesar de sentir el impulso de contestar, no tuvo la fuerza para hacerlo. Dos timbrazos más. Niza estiró el brazo por encima de él y levantó la bocina.

—¿Bueno? . . . Sí, un momento. Te buscan.

Moroni entreabrió los ojos frunciendo el ceño. Se pegó el auricular al cachete y carraspeó, sin levantarse de la cama.

—Sí. ¿Cómo? —Larga pausa—. Está bien, hermana. Gracias.

Colgó. Se quedó acostado con los ojos muy abiertos mirando al teléfono. Supo que no sería la última llamada en la noche y deseó con todas sus fuerzas que no le importara un pepino.

—¿Hermana? ¿No que eras hijo único? —Niza comenzó a acariciarlo con la intención de hacerlo voltear.

Estaba casi desnudo. La trusa gris oscuro que tanta libertad le hacía sentir, ahora acentuaba su carencia y su orfandad. Pensó en sus gárments, esas prendas interiores que había dejado de usar hacía años, a pesar de su significado sagrado. Los extrañó. De pronto lo molestó la caricia: le pareció que se volvía obscena.

—Me tengo que ir.

—¿A esta hora?

—Tengo que salir.

Niza volvió a su sueño y Moroni se levantó.

Todos sus impulsos estaban amplificados. Frenéticamente sacó de un cajón recóndito un largo bóxer blanco y una camiseta que completaba el juego. Olían a polvo. Con la prisa de un colegial se metió a la ducha y dejó que el primer chorro de agua fría le cayera en la cabeza hasta alcanzar la tibieza usual del baño. Se lavó minuciosamente, como queriendo eliminar aromas que tenía tatuados por toda la piel. Deseó no tener que cargar el peso de su vida y decidió que el sentimiento más legítimo que podría tener para lidiar con él, sería la intención de sacar inmediatamente a Niza de su vida: levantarla a gritos de la cama y echarla de su departamento con lujo de violencia, impulsado por una convulsiva indignación moral.

Pero ella no tenía la culpa, a fin de cuentas. La conoció fortuitamente, como a sus últimas tres parejas sentimentales. No eran novias, tampoco amigas. Vamos, no eran siquiera amantes, esa es una palabra muy cargada de aventura, de cínica alegría. Es más: eso de “sentimentales” era uno de tantos eufemismos para referirse a lo meramente carnal. Pero en este caso no era solamente carnal. Había una historia. Había horas de plática y compenetración fertilizando las tensiones que se distendían en la noche.

Se dedicó a revivir, como si al hacerlo pudiera purgarse de ello, el difuso momento en que decidió que jugaría el juego que Niza le proponía. Descubrió que había entrado en esa dinámica por puro aburrimiento, porque su soledad le estaba pesando y le preocupaba que la gente creyera que ese aislamiento era el reflejo de alguna perversión. No podía permitirse ese riesgo social. Si bien no le importó admitir ante sus socios y empleados que Sandra le había pedido el divorcio, fue únicamente porque las familias rotas son lo más común de nuestro mundo, aún entre los miembros de la iglesia. De modo que “el que esté libre de pecado . . . “

Pero qué demonios importaban los hermanos si desde que Sandra se fue, él se alejó cada vez más de ellos. Se rió de sí mismo y se llenó de un reproche autoinfligido por no ser capaz de cumplir sus intenciones de ser fuerte, salir a flote y demostrarle a su hija, a Dios y a sí mismo que se sobrepondría a la adversidad y que era mejor que muchos de los que entonces lo señalaban, incluido Lenin, quien no conforme con haberlo condenado a las tinieblas de afuera con sus petulantes predicaciones, ahora le salía con el capricho de interrumpirle el primer sueño profundo en años, a la mitad de una noche inopinada de embriaguez, y en la que acaba de tener casi dos horas de apasionada intimidad.

Se puso su ropa interior blanca mascullando lo poco que recordaba de las explicaciones que se dan sobre sus símbolos. Seguían oliendo al polvo que se acumula cuando la ropa queda mucho tiempo guardada. Por un momento creyó que si tomaba suficiente aire para emitir un suspiro, ese polvo de sus gárments lo haría toser, así que reprimió su aspiración y ello le provocó un bostezo que acompañó con un jadeo sonoro rayano en estertor de muerte.

Arrinconado entre los desodorantes y los protectores solares, estaba un viejo frasco de Eternity For Men. Se roció debajo y encima de la ropa, y el penetrante dulzor no sólo cubrió el aroma que se quiso quitar de su piel en la ducha y el olor a polvo, sino que lo ayudó a convencerse de que, si veía a Sandra, ella reconocería la fragancia de su primera cita.

Niza lo seguía atentamente con sus oídos. Llevaba durmiendo ahí un par de semanas. No vivía ahí. En el clóset sólo había una muda de su ropa y zapatos. Llegaban juntos en la noche, después de cenar, bailar o pelearse, y apenas cruzaban el umbral del departamento, repetían ritualmente lo que pasó la primera vez: un silencio incómodo los envolvía. Eludieron el trámite de sentarse, platicar y seducirse, y como huyendo de la sala, se refugiaron en el dormitorio con la rapidez y la seriedad con la que un niño maltratado se va castigado sin cenar. Entre sonrisas nerviosas, se desnudaron y se acariciaron febrilmente antes de unirse con torpeza en un desagradable paroxismo digno de dos estúpidos adolescentes que creen que esa sensación de estar haciendo todo mal es señal de estar haciendo las cosas bien. Durante la meseta de su trance, fingían con gritos y gemidos alcanzar el máximo placer, que ciertamente llegaba, pero de un modo tan incierto que ninguno de los dos se atrevía a preguntar ni a reclamar ni a disculparse por nada. Para ella, él era un amante tierno, suave, delicado y casi infantil incapaz de hacerle daño. Por eso estaba perfectamente dispuesta a perdonarle su poco ímpetu.

Él estaba muy cansado siempre. Y era verdad. Lo único que lo hacía responder con ella era saber que, de fallar, la más grande humillación sería una marca en su frente que nunca podría borrar, como los aromas que llevaba tatuados en su piel y que tuvo que disimular con Eternity.

El teléfono sonó de nuevo. Corrió a la sala a descolgar la extensión para que Niza no se molestara en contestar. Se llevó la bocina a la oreja sin decir nada. Tras dos segundos de espera, escuchó un “¿Bueno? ¿Eres tú?” al que no respondió para nada. “Supongo que ya te dijeron”. Más silencio. “Sólo quería saber si estás bien”. Obstinado silencio. “Pues eso era todo. Bye”.

Era la voz de su hija. No la de quien esperaba.

Se puso una elegante camisa blanca sin planchar, un suéter negro y un traje gris óxford con ese corte tan de moda que le hace resaltar la anchura de su espalda y parece inflarle el pecho. Tomó del corbatero una vieja e insulsa corbata que no usaba desde hacía más de quince años. Nunca pensó en descolgarla para guardarla en alguna maleta de recuerdos, mucho menos en tirarla. Era sagrada, casi un amuleto. Mientras se hacía el nudo le sorprendió darse cuenta de que no olía a polvo, sino a recuerdos.

Casi de modo automático se sirvió una taza de café para despabilarse, pero cuando la alzó para tomarlo, se vio reflejado en el oscuro espejo tremolante, donde aparecía con su camisa blanca, traje y corbata, y la visión le causó un espanto instantáneo, similar al sobresalto que llega cuando se descubre una araña entre la ropa doblada.

Tomó las llaves del auto y cerró de un jalón la puerta. Aún estaba muy oscuro afuera.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue