Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 2

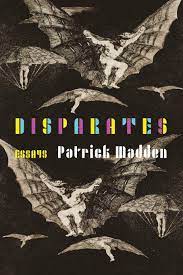

Review: “Babbling on toward Ephemeral Patterns” Patrick Madden, Disparates

Alphabetize your

Disparates, 134

karma, sever your qigong,

jinx your wifi code.

I want to suggest that Disparates is less disparate than it claims to be, that there is a running theme or a coherent message that bubbles up through the macadam of its thirty-one distinctive essays. But I think I only suspect this, perhaps in part because of the recurrence of devices (“dialogues” with other writers) and figures (family, mostly, and a friend or two who make more than one appearance), and a gainly insistence on strangeness throughout: if the collection has a rule, it is the Rule of Un-expectation.

The title of one of Madden’s essays, “The Arrogance of Style,” provides a clue to his overall sensibility: the rhythmic, omnipresent contreculture irreverence of the comic essayist. “Up yours, Strunk & White!” he seems to say.

His own style, even in playful departures from already playful variations on standard prose, is the perfect union of Victorian lugubriousness and modernist minimalism, which is not to suggest it is the proverbial lovechild of Dickens and Hemingway but is rather a real marriage: a tumultuous and somewhat practiced negotiation, and all the more productive for it.

The negotiation, as in “In Step with . . . Montaigne,” is expressed further in Madden’s “dialogues” with other writers. Madden “features” other writers, in much the same way a nineties pop diva might feature a rapper, playing off ideas he likes, principles that capture or spark his own imagination, and difficulties that score and tend his stubborn play. Anxious of influence, torn between lovers, caught between scintillae and the charity of his disposition, Madden “plays” in and with the tension of style as a matter of choice, of intention, and not merely of accident or expression.

Ultimately this is a negotiation or a conflict (though “conflict” is too strong a word: the “play wrestle,” then, of the child uninhibited) in Madden himself. In “Alfonsina y el Mar,” he reflects on his own tendency to advise others to “[c]ontrol [their] metaphors” and “give them some relation to your subject, or at least a relation to one another” (59). Given Madden’s assiduousness, his confessed willingness to critique, his own writing feels like a surrender to forces more chaotic and divine, to the creative madness of allusion and the unstoppering of bottles, the wanton unwrapping of chocolates without consulting the key.

Game, illusion, or extended aside, the essays remind us or show us as if we already know what Madden is telling us: we supply the connections between the disparate things—our minds dream up connections, fill in the gaps in a Rube Goldberg machinery in which we are, simultaneously, parts.

For example, in “Order,” the essayist (not just Madden) tells stories, weaves phrases, and follows the leads of language and of life, of life and of language. This is discovery, not invention; this is equally invention, not discovery. I suspect that much of fiction is akin to this in its capturing and dissemination of truth, however unintentionally, and that much of what passes for truth is entirely a fabrication, or lifted from somewhere else: that the deeper truths of human telling are fictions or plagiarisms or both. Even when Madden’s play strains credulity, playfully or confessionally (143), it all feels true and of a piece until, and especially when, out of stubborn play, “the essay veers, requires both my and your consciousness to care and to make something” (104).

And the essays do veer, requiring something more of us and of him. In “Beat on the Brat,” Madden describes a brutal assault on a developmentally disabled teenage girl by peers and occasional associates of his (104), near enough to slam the screen door on an otherwise simple and sweet adolescence: hers and his (though mostly hers, he’s mindful). There but for the grace, we murmur, might we be both victim and villain. The event is marked in a rumination on a labored and half-assed celebrity repentance—a portrait of the essential and sometimes delayed acceptance of growth—but it has changed things, irrevocably (122).

You see, for much of the collection—in “Solstice,” for instance—one feels as if one is inside a complex, sustained, erudite dad joke. And then the joke ends, and shit gets real, and the only comfort to be had is the assurance that thus it has always been, and always will be: suffering is peppered, one can hope, with moments of relief or even jubilation that are themselves real and not figments of some powerful one’s imagination: real joy, real relief, even in and among suffering.

Elsewhere, near and far from me, my fellow beings spun other Pokéstops and attended other wedding receptions; joyed and sorrowed at goals and misses; sat writing staring at other mountains, or oceans, or forests, or brick walls, or trash heaps; made futile efforts to stave off the encroaching entropy. Others danced and drummed and sang, some at monuments long ago constructed to mark the northernmost place where the sun stood still in the sky. Underneath it all, the earth wobbled slightly as it spun unaccountably fast, imperceptibly fast, as it continued its seemingly interminable revolutions, barely noting the significance of once again leaning fully toward the sun. (148)

So while it isn’t true that the book is frivolous/playful right up until the end—“Repast” and “Expectations” are both meditations around Madden’s mother’s life and passing that precede the turn—it feels like it is. Perhaps this is because of the way these middle meditations are framed: against a backdrop of play, protectively, to stem the tears. Perhaps also because Madden has already called his own sobriety of mood into question: “So what?/So there” (30); and, “Too aware, too intentional, have I become” (45).

But I suppose that groundwork—the core uncertainty that he is ever serious, or ever should be—is what makes the swerve all the more poignant. In “Inertia,” Madden “smile[s] at the incongruities of existence, the recursions and extrapolations, the way experience seems to close upon itself but refuses to shut” (87). Nay, I know not “seems,” I want to reply, grasping at certainty. But maybe he’s right. “Seems” is all we know, and—the ending of this one is masterful—insisting upon and producing open-mindedness, aperture, and the feeling that one has been invited to a party at which one might be the only guest, and quite possibly also the host.

We arrive, after all and perhaps, with “Chesterton, recognizing/describing/excusing/asserting the essay that ‘does not know what it is trying to find; and therefore does not find it’” (61). These essays—the essay/the essay—are embodiments of that principle: we still haven’t found what we’re looking for, perhaps because what we’re looking for evolves with us, in advance of us, and looking back makes that poignantly and sometimes painfully clear. So we don’t stop looking. We can’t. Essays—these essays—“juxtapose / mundane and queer, believe the / weight, reck the fazing” (128). Incidents of tension and accidents of intention are all there is, even when there’s purpose.

The book doesn’t stay entirely serious once it veers, anymore than it had been altogether frivolous before: “Against the Wind” and “Pangram Haiku” are satyr play, and pleasant relief. “Plums” follows as well, with a little WCW thrown in to keep Shakespeare, Bono, and Seger company in ever-gentle and productive play: there is sweetness to soften the bitter taste of suffering, no more real than pleasure or joy, but always, as always, sharper and louder.

So take it as I give it: shit does, indeed, get real. And then consider that this settling into seriousness feels organic, though it may not be. Perhaps Madden became self-conscious of the otherwise frivolity of his process and its conceit, or perhaps arrived quite naturally at something profounder—by the very form of association he had been following all the while. Perhaps these materials were already in the collection but dropped in other locations and one or the other, writer or editor, decided that their poignance was wasted where they were, that drawing this collection to a close was like drawing a life, or a screenplay, to an ending: less a denouement than a recognition that serious things live alongside the strange and playful. I don’t know. But Disparates ends beautifully, the quiet seriousness of the last essays providing the strangeness that has pervaded and shaped the whole, even as they step away from play for its own sake and see in play a way to deeper and more sober reflections, the finding of truths and not just trinkets, even if it wasn’t looking for them.

Q: So, Dr. Penny, should I purchase, borrow, steal, download, but in any event read Disparates?

A: Yes, and then be sure to send the author all your many questions, the less relevant or apropos, the better.

Or better yet:

Drink the water.

Memorize the lyrics, ideally inaccurately.

Weep when appropriate.

Laugh when natural.

Essay daily.

Enter into joy.

Patrick Madden. Disparates: Essays. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020. 186 pp. Paperback: $22.95. ISBN: 978-1-4962-0244-4.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue