Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 4

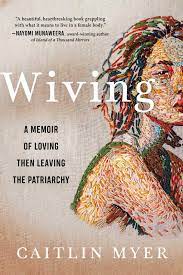

Connecting the Dots Caitlin Myer, A Memoir of Loving and Then Leaving the Patriarchy

When I was a kid, I loved doing dot-to-dot pictures. Do you know the ones I’m talking about? You began with a sheet of paper scattered with dots and tiny numbers, like a starry but constellation-less sky; any star could have any relationship to any other star. Unlike the dot-to-dots my kids do nowadays, there were no solid lines already on the page back then—no faces or wings or puffs of smoke hinting at what the final image would be. The only way to figure it out was to start moving your pencil around the page, tracing a line from dot 1 to dot 2 to dot 3 until an image began to emerge.

Reading Wiving felt like doing a dot-to-dot. It is one of those memoirs that begins at the end, or close to the end, and then takes you on a circuitous journey, zigzagging between years—from 2020 to the aughts to 1974—before bringing you back around to the present. The joy of this book was in connecting those dots and seeing the surprising route the narrative took through the pages. With each new chapter, another dot revealed itself, and I traced a line from the dot that came before it to see what picture I would end up with.

The book begins in Portugal, close to the present day. Myer is fifty years old and has just moved to a coastal town. She says, after recounting an experience with a man leaning in for a cheek kiss and then suddenly turning his head and forcing his tongue into her mouth, “Being a woman is hazardous” (2). We don’t know how she has ended up here, living alone in a country where she hardly speaks the language. We only know that she wants to be alone and no one seems to want to let her.

In the next chapter, another dot appears when we find out that fourteen years before Portugal, there was a marriage and trying for a baby and bleeding—months and months of bleeding. There is so much blood that it doesn’t seem possible that one person could bleed so consistently and prolifically. Myer becomes weaker and weaker, eventually needing a transfusion. Her doctors can’t figure out why this is happening, but they offer a solution: a hysterectomy.

And then, the week she is scheduled for the hysterectomy, a new dot is revealed when there is a call from home. Myer’s mother has died. (These aren’t really spoilers, by the way. All of the events I just mentioned occur within the first ten pages of the book.) And so, it continues on like this. From the mother’s death, we trace a line back to Myer’s childhood in Provo, Utah, where she grew up in a large LDS family, the youngest daughter of a BYU art professor father and a frequently sick poet mother. She leads us through her chaotic childhood, one in which she is constantly dancing around her mother’s illnesses and the expectation that she will one day become a wife.

Growing up in the church, Myer is keenly aware that she is meant to be a wife. She seems to be an ancillary character in the story of her own life instead of the author. She writes, “Once upon a time, Eve was created to fill a man’s need. She sprang from his rib but wasn’t free, she was hooked to him, defined by him, her daughters’ destiny written at the beginning of the world. The woman’s reason for being centers on the man” (48). She recounts heartbreaking tale after heartbreaking tale of the hazards of being a woman. Myer’s story is one of (slowly, achingly) untethering and undefining. The prose is lyrical, the narrative is fragmented, and Myer’s voice is blisteringly honest.

A word of warning here: this narrative goes to some very dark places. It covers mental illness, multiple sexual assaults, and an attempted suicide in the seminary building. It is obvious that Myer has done a tremendous amount of healing, but she does not hold back, does not try to massage these events to make them more palatable for her reader. As a result, I often had the impulse to look away. But I decided to stay with it because I felt that I was bearing witness to Myer’s trauma. This might not be the best call for all, though, so proceed with care.

These tough moments are cut with moments suffused with great tenderness. When Caitlin is in a psych ward after her suicide attempt, for example, her father comes to visit her with a piece of paper and a charcoal pencil in hand. He then goes on to lovingly teach her how to draw a face.

The eyes, he says, are halfway down the face.

No way, I say.

It’s true. We’re all forehead. Me especially, he says, laughing, rubbing his hand over his bald head. He leaves a streak of charcoal on his skull. (104)

This is a memory Myer will return to again and again.

In the dot-to-dot pictures of my childhood, my pencil sometimes followed a predictable route. One dot led to the dot closest to it. But other times, the trajectory was unexpected. The next number suddenly had me zipping diagonally to the bottom corner of the page or back into a section of the picture my pencil had worked through much earlier. This kind of work can be, at times, disorienting. Looking at the closest dot, you think: Why isn’t this the next move? But the thing is, even if it’s the closest dot, going there won’t necessarily lead to a final picture that makes sense. Going to the closest dot could mean you end up with a dog without a tail, for instance. Some might similarly find Myer’s route to be baffling. But once I finished the book, all these points added up. While the picture of her life might not be the one you expected or the one you would choose for her, that, for me, is the point. She is aware that the life she has created might not lead to a pat ending, that she might not end up happy. Throughout the book, Myer compares herself to her mother, whose potential is never fully realized. Instead, her mother increasingly spends her days in bed. She says, “Mom suffocated her rage until it nailed her to the bed. I let mine pull me forward, carrying my bed on my back. I might land myself an emptiness as great as my mother’s. An open question. Solitude is terror, and I am walking directly into its eye” (242). Myer has made bold decisions. I was happy to trace the points along her journey and to see the portrait that finally emerged—a portrait of her own making.

Caitlin Myer. Wiving: A Memoir of Loving and Then Leaving the Patriarchy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020. 283pp. Hardcover: $14.99. Kindle: $18.83. ISBN: 9781950691470.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue