Articles/Essays – Volume 56, No. 3

Eve’s Choice

Listen to an audio version of this piece here.

We understand the controversial nature of the problem. Millions of Americans believe that life begins at conception and consequently that an abortion is akin to causing the death of an innocent child; they recoil at the thought of a law that would permit it. Other millions fear that a law that forbids abortion would condemn many American women to lives that lack dignity, depriving them of equal liberty and leading those with least resources to undergo illegal abortions with the attendant risks of death and suffering.

From Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority opinion in Stenberg v. Carhart in 2000. The ruling struck down a Nebraska law that made performing a “partial-birth abortion” illegal.

When a subject is highly controversial—and any question about sex is that—one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one’s audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the prejudices, the limitations, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

All the cousins knew Aunt Marla’s story. Her doctors in Salt Lake City said it was unlikely she could survive a pregnancy. So she and Uncle Bill adopted two beautiful children. Then, several years later, Marla had an unplanned pregnancy. Her obstetrician refused to consider an abortion, even though keeping the baby to term might result in her preventable death and two motherless kids. Bed rest. Lots of worry. Plenty of anger directed at our very own LDS Church.

But Betsy was born. She was dangerously premature—especially so for those days. Everyone said that at birth she could have fit on a dinner plate (an image that haunted my young imagination). She wasn’t expected to survive. But she did. Perfect, whole, healthy.

This story isn’t going where you think it is. It would be understandable if Betsy herself had become an argument, an important family story, that challenged abortion. But somehow it never did. The grown-ups we kids looked up to—our parents and grandparents—were New Deal Democrats. Some had broken with the Church. Some, like my parents, were weaving their LDS faith with progressive politics in an unconventional way. We felt the gratitude they all had for the miracle that was Betsy, but we also sensed their sorrow and anger for the horrible trap Marla and Bill were in before their daughter’s birth. Hypocritical? It didn’t feel like that to us. Several years later, my family moved to the East Coast, where my father, a physician by training, had left his practice to become dean of admissions at Harvard College. On a car trip home from summer vacation, I remember my parents discussing the recent Roe v. Wade decision. As my mother drove, my father turned to us kids in the back of the station wagon (wriggling around as usual in those pre–seat belt days). Suddenly somber, he looked us in the eyes and his features sharpened. “An abortion is a very sad thing.” He paused, bracing himself. “But a child coming into this world unwanted is tragic.”

It is in this context that I grew up a faithful member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Despite being at odds with the Church’s mostly male leadership who considered abortion “one of the most revolting and sinful practices in this day,”[1] my parents found deep satisfaction and belonging in our faith community. They taught by example how to walk with my coreligionists, especially when I disagreed with them. They encouraged me to turn to my own spiritual experiences and the fundamentals of LDS doctrine when I had questions, when I felt alone in my interpretation of God’s will. Our religion has not historically been a very big tent, but a small and hardy band of politically progressive Latter-day Saints (who frequently quarrel with one another) continue to hold some space inside that tent like our hero Senator Harry Reid did. And now, as a powerful alliance of my fellow citizens, elected officials, and Supreme Court justices have begun returning us to the circumstances my aunt faced in the 1960s, I have been thinking about why I persist in the conviction, based upon my faith, that a woman’s right to control her reproductive destiny is a sacred thing.

In LDS doctrine, Eve is the hero of the Eden story. The way we tell it, she and Adam were given conflicting commandments: multiply and replenish the earth, yet stay away from the tree of knowledge. They couldn’t do both. So Eve sacrificed the static peace of the garden for the messy growth that only mortality—including the bearing of children—could provide. Ironically, we believe that Satan’s attempt to corrupt humanity actually put us on a path toward salvation. We fell forward. Latter-day Saints give Eve full credit for making the right choice, even though this was God’s plan all along. The current president of the LDS Church, Russell M. Nelson (who, like his predecessors, teaches that most abortions are sinful), put it this way: “We and all mankind are forever blessed because of Eve’s great courage and wisdom. By partaking of the fruit first, she did what needed to be done. Adam was wise enough to do likewise.”[2]

The first reproductive choice I made was deeply informed by my spiritual life.

My adolescence was blessed by the example of women in our congregation who joyfully raised large families while skillfully attending to their personal growth. True to my comfort with juxtaposition, I married my boyfriend (he converted to Mormonism) while still an undergraduate at Harvard. Our friends just shook their heads. This was the eighties: no one was getting married. But Shipley and I were all in: living an off-campus Love Story plot without the tragic ending. Also unlike most others in my cohort, I wanted babies—lots of them—ASAP, even though I didn’t have a clue as to what my career goals were.

But motivated procreators though we were, my husband and I were realistic; we couldn’t afford a child right away. I’d get my BA, support him through graduate school, and then we’d start a family.

A few months into graduate school, my husband reported a vivid dream. He was sitting in an assembly of some kind in the upper room of the iconic LDS temple in Salt Lake City, the holiest of places where we make covenants with God and honor our ancestors. In the dream, everyone was dressed in white. It gradually dawned on my husband that the man sitting next to him was the president of our church at the time—our prophet, seer, and revelator Spencer W. Kimball. The old man turned to my husband, put his hand on his knee, and in his trademark gravelly voice said, “You know, I think it’s time you and Erika start a family.”

That was all it took. We stopped the birth control and figured the Lord would provide. What we didn’t know was that it would take us almost two years to get pregnant. Our first child arrived six months after my husband’s graduation, at which point we had a good salary and health insurance.

The irony that I was completely receptive to a man’s dream about a man’s instructions concerning what my man-God thought best is not lost on me. But more important to me than the gender of the messengers was the experience of God speaking to me about my unique situation, a basic tenet of Latter-day Saint doctrine. The good news that “the heavens were not closed” is an essential part of our religion’s origin story. Farm boy Joseph Smith took to heart a scripture from the Book of James and went to the woods to ask God a question about which church he should join.

If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.[3]

When Joseph Smith walked out of those woods, he later reported a vision: God had a glorified body of flesh and bones. Like the heretical Christian mystics of centuries ago, Latter-day Saints embrace imago Dei, humans in the image of God, as an all-encompassing principle. Not only are our intellect and spirits divine, but we believe our bodies are as well and have the potential to be glorified in the hereafter. We go so far as to believe that ultimately, in the world beyond this one, we have the capacity to become gods. This doctrine, while understandably troubling to many Christian faiths, abides deeply in me. “As man now is, God once was: As God now is, man may be,” proclaimed church President Lorenzo Snow in the 1880s.[4] So what we learn from God about the bearing and raising of children in this life, we consider a prelude to becoming godlike creators in the hereafter.

Human agency, access to divine inspiration, and the holy responsibility of bringing children into this world: these are core LDS beliefs that, when it comes to abortion, result in my struggle with the institutional LDS Church.

On a balmy September evening in 2020, a text popped up from my neighbor Anne: I need to talk about abortion. She suggested a walk with me and our friend Katherine. My husband and I had just tuned in to the first US presidential debate of that election and the shouting had begun. I was happy to leave.

We three women are in the same congregation. I’m an old mom with adult kids and grandkids; Katherine has four school-age children. She leans left politically, and as we started talking, she expressed her frustration with pro-life stances that don’t include government support for low-income, single parents. Anne is younger, a doting mother to three-year-old Jacob. He was now thriving, but this little boy had spent six scary weeks in the hospital close to death with a respiratory condition. Anne and her husband dearly hoped for a second child but were unsure if that would ever happen. She was torn. She wanted to support women in the awful place of an unwanted pregnancy; her Christian principles informed her reluctance to shame or blame. But those same principles celebrated the magnificence of God’s creation—even his potential creation. It was very hard for her to feel okay about easy access to abortion. She was a careful consumer of social media but couldn’t ignore the horror stories she’d read online about late-term procedures.

As Katherine and I listened to Anne, we all felt gratitude for that moment. In contrast to the campaign vitriol that was being broadcast, streamed, memed, and tweeted in real time, we could show up in real life for each other. As the sky darkened and the stars emerged, I talked about my miscarriages: sad, early-week interludes during my childbearing years. I remember my private panic at a Christmas party when I discovered I was bleeding. Once home, I lay in bed with the quilt my mother had bought for her anticipated grandchild. When I closed my eyes, I saw a female spirit leave my presence and return to some cosmic waiting room—a cartoonish yet comforting vision. I was spared the deep sorrow that others endure; at that time, I had two little boys who were keeping our family humming. It took another year for my daughter to arrive, then our third son, then another miscarriage (this time on Thanksgiving), and at the end of a sixteen-year reproductive run, our second daughter, baby number five.

We stopped in the dark at a playground, and the lights blinked on. I remembered another story, one unique to my faith tradition. In the Book of Mormon (LDS scripture as opposed to the Broadway musical) there is a scene where Christ speaks to a prophet named Nephi on the American continent. Nephi has been praying for his people, who are under death threat for believing the prophecies of Jesus’ imminent birth on the other side of the world. Nephi is comforted when he hears the voice of the Lord saying, “be of good cheer . . . on the morrow come I into the world.”[5] Jesus the spirit speaks to Nephi, while Jesus the unborn awaits birth in Bethlehem. I explained to my friends that this story resonates with my own experience of bringing children into the world. Mortal incarnation is a process, not a moment. It belongs to me and my God.

When we three parted that night, we hadn’t convinced each other of anything except that this time together was precious.

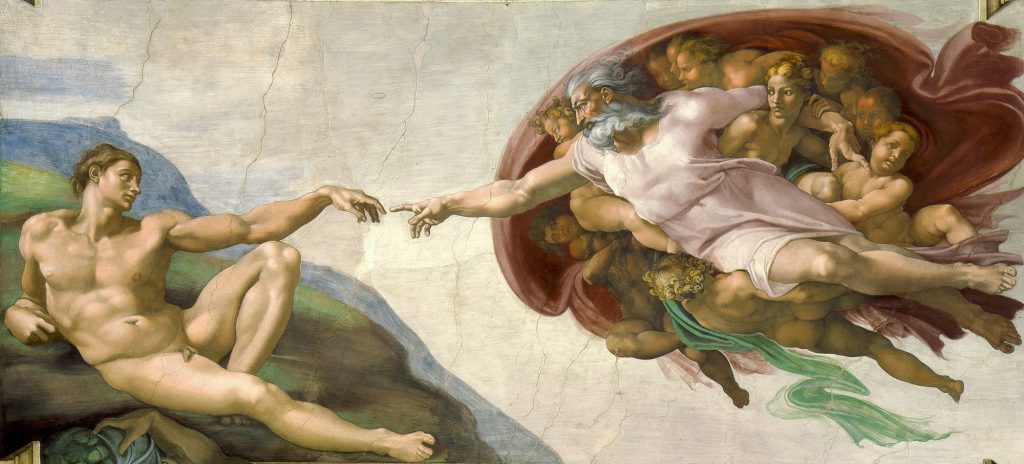

Last December, as I was preparing our empty nest for the Christmastime return of children and grandchildren, I found myself in need of something heavy to flatten out the curving edge of a basement rug. I turned to a shelf of neglected college books and found Michelangelo, the Painter by Valerio Mariani. It is a comprehensive tome, much of its attention given to the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The book gave a satisfying thump as I dropped it onto the carpet, the perfect tool for the job. It lay there, weighing down the carpet for a week until, prompted by my recent search for understanding around creation, I lugged the book upstairs.

Curling up in my reading chair, I opened the book on my lap. Carefully turning the pages, I made my way through colorplate after colorplate to The Creation of Adam, an image that has become iconic in Western culture. The Lord is on the move through the cosmos to bring life to Adam. The wind blows back God’s hair and beard. His celestial clothing ripples. Bearing him up and attending to his royal drapery, seraphim and cherubim play entourage.

I have always loved this painting for its contrast: God’s overflowing force of creation approaches Adam’s lifeless body. Adam’s delicate, downturned hand awaits quickening. But this time around, I saw more. Adam’s body lies in beautiful Renaissance repose, yes, but lifeless? No. His muscles are defined; his flesh is the same golden chiaroscuro tones as the Lord’s. Adam’s eyes do not stare blankly; he’s looking straight at God. Certainly his heart is beating. Yet just as certainly, something is still missing. Although Adam’s body looks youthful and strong, he has no soul.

I look back at God and his crew. Tucked under his arm is a figure different from the angels. A mature woman. It’s Eve, and she’s paying close attention to God’s outstretched hand. It is as if he has told her, “Watch how I do this; it’s going to be your job from now on.” Her eyes are fixed on the most famous detail of this fresco: the fingers that almost touch. Tonight, I am drawn to the space between the fingers: the space between God and the fully incarnate human. I believe that space belongs to women. It is heartbreaking when the state lays claim to it.

I am grateful for the early training I received in managing the tension between my personal spiritual experiences and whatever the current policies of my church may be. I’ve been at this way too long to abandon either my politics or my church. And at this polarized time in American history, people like me—pro-choice members of conservative faith communities—have a special role to play. We can bear witness to the sanctity of female reproductive agency, not in spite of but because of our religion. We can march, fund, and vote in the public square. But it is crucial that we do all these things while staying in relationship with our pro-life brothers, sisters, and siblings within and without our churches. We do this best the way we always have: by serving, praying, and caring together. Like saints in a Renaissance painting who gather round an altar, we must engage in holy conversation, pondering God’s will for a mother and a child.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Spencer W. Kimball, “Guidelines to Carry Forth the Work of God in Cleanliness,” Apr. 1974.

[2] Russell M. Nelson, “Constancy amid Change,” Oct. 1993.

[3] James 1:5.

[4] Eliza R. Snow, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Company, 1884), 46. See also The Teachings of Lorenzo Snow, edited by Clyde J. Williams (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1996), 1–9.

[5] 3 Nephi 1:13.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue