Articles/Essays – Volume 57, No. 2

“They Have Received Many Wounds”:Applying a Trauma-Informed Lens to the Book of Mormon

Trauma decontextualized in a person looks like personality. Trauma decontextualized in a family looks like family traits. Trauma decontextualized in a people looks like culture.

Resmaa Menakem[1]

Introduction

The field of biblical studies has made significant inroads in understanding scripture through a trauma hermeneutic in recent years, with efficacious results.[2] Biblical interpreters using the lens of trauma have drawn on the fields of psychology, sociology, comparative literature, and refugee studies to understand scriptural text in new ways. A trauma hermeneutic (or trauma-informed lens or reading) not only recognizes the ways in which the experience of trauma immediately affects individuals but also how trauma ripples through generations and communities and how the text may reflect the effects of unprocessed trauma and play a role in healing from traumatic events. Rather than a single method of interpretation, the field of biblical trauma studies has created a “frame of reference” that draws on many different trauma theories and is intended to be coupled with other diverse forms of biblical criticism.[3] It is “a fluid orientation, or sensitivity in reading with different possible emphases.”[4] Yet this “heuristic framework”[5] has been severely underutilized in readings of the Book of Mormon, a scriptural text that contains an abundance of stories of traumatic events. Two important exceptions to this are in the work of Deidre Green and Kylie Nielson Turley, both of whom have brilliantly used a trauma-informed hermeneutic to yield fascinating insights into the characters of Jacob and Alma.[6] This article will explain what trauma is and how to be trauma informed, describe a few examples from the Book of Mormon in which a sensitivity to trauma could reveal greater insights from the text, and argue for the importance of using a trauma hermeneutic. We conclude with an application of a trauma hermeneutic in religious settings and an argument for the importance of being aware of how scriptural trauma may interact with the potential trauma of readers.

Defining Trauma

The word “trauma” has become a modern buzzword, often applied to contexts or situations without a clear understanding of the term. Literally “wound” in Greek, trauma can be physical, such as the physical trauma to our organs resulting from a bullet wound, or psychological, such as the mental and emotional trauma we carry with us after an upsetting or violent event. Trauma “results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”[7] Psychological trauma, the focus of this article, can be understood by examining (1) the event, (2) how it is experienced, and (3) its effects.[8]

Trauma can occur on a macro or micro scale. Macrotraumatic events (also called communal trauma) simultaneously impact a large group or a society, introducing long-term consequences with which members of the group must grapple with for many years. These include natural disasters, wars, mass shootings, pandemics, and other violent or destructive events with the power to upend many lives. They can also include institutional action or inaction, such as a church or university covering up abuse or failing to protect marginalized individuals.[9] Though the situations at the heart of such institutional trauma may directly impact only a small number of individuals (e.g., those abused by persons in power), the implications of an institution protecting abusers or failing to act when its members were harmed can trigger ripples of distress, harm, and distrust across the institution, leading to a macrotraumatic event. Microtraumatic events hold the same power to upend lives and destroy mental health as the macro events, though these typically impact a smaller number of people at once. Micro traumas can include familial events such as abuse, death, or divorce; experiences of or exposures to community violence such as assault, exploitation, or bullying; or any other interpersonal or individual event that causes injury, shame, or other physical or psychological harm for those involved.[10]

Trauma can also be passed intergenerationally in various pathways, including biochemically, culturally, and narratively. Biochemically, trauma can be inherited via epigenetic effects wherein markers at the chromosomal level are passed across the generations. Culturally, it may be taught via parenting practices or familial expectations. These pathways may be closely intertwined. For example, a Jewish mother who has survived the extermination camps of World War II may pass the trauma of that experience to her children in their inherited epigenetic markings and through her discipline and nurturing practices, both of which were shaped by the trauma she experienced.[11] These inherited traumas may then be passed to her grandchildren both epigenetically and by the parenting and mental health of her children in their parental role. Collective trauma can be transmitted intergenerationally, as a massive, macrotraumatic event can disrupt “the fabric of communal life, changing core social institutional and cultural values.”[12] These shifts impact not only those alive who experience the traumatic event but the society and culture into which future generations are born.

Narratively, trauma may become an integral part of a group’s shared history.[13] Examples of this can be seen in calls to “never forget” from a community following a terrorist attack or from an ethnic group targeted in a genocide. Collective group-based traumas can have far-reaching effects on the well-being of group members. Collective trauma not only creates psychological wounds that can exist for generations but also shapes the stories used to understand these wounds and the manner in which members seek to build resilience and overcome these adversities. Whether named or ignored, trauma shapes the individual lives and collective communities or cultures that it touches.

A Trauma-Informed Hermeneutic

Knowing the definition of trauma is different from being trauma informed. To be trauma informed means to approach an individual, group, or context with a view and understanding of how they (or it) has been shaped by trauma and adjusting the approach or expectations of the person(s) based on this understanding.[14] To use a trauma-informed lens means to shift perspective from a critical, accusatory one of “What is wrong with you?” to a more sensitive, person-centered one of “What has happened to you? What have you experienced?”[15] Because trauma is a nearly universal experience, the trauma-informed approach is not siloed to only those providing psychological care to trauma survivors; instead, it is a lens that can allow us all to see the humanity and the history of the individuals, groups, and cultural traditions surrounding us. The trauma-informed lens can be flexible in its application and has space for considering how context, culture, and history impact how individuals process events and the impact these potential traumas have.

A trauma-informed lens allows us to interpret how someone’s trauma history may affect their behavior and beliefs and reminds us that our language and actions should be adjusted with others’ traumas in mind. This lens is a reminder that “trauma shapes our thinking” and the thinking of others “in ways that are both explicit and hidden.”[16] To be trauma informed is to allow our understanding of trauma to influence how we interpret the world and what we put out into the world with a recognition of both the traumas of others and the personal traumas we carry.

Using a trauma-informed hermeneutic means considering how trauma affected and continues to affect writers and readers of the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon is a text unusually focused on human suffering: war, rape, famine, abuse, murder, slavery, natural disasters, and other forms of violence all occur within its pages. As Helaman states in the book of Alma, “They have received many wounds.”[17]

We propose that a trauma-informed hermeneutic is a valuable lens through which to consider the Book of Mormon, as it empowers readers with unique tools and perspectives on the text. A trauma-informed lens applied to scripture (1) inherently acknowledges that a reader does not have a complete understanding of the text unless the effects of trauma on individuals within the text and on the narrative as a whole are considered; (2) allows for alternate interpretations of the text, including symbolic representations of violent or traumatic events; (3) complements historical and literary approaches to scripture via an examination of the impact of trauma on individuals and communities and via the creation of survival literature; (4) can help a reader approach the text, its characters, and its writer(s) with increased empathy; and (5) facilitates the transformation of disturbing passages of scripture into healing ones.

Methodology

As Grant Hardy has noted, the Book of Mormon is “first and foremost a narrative, offered to us by specific, named narrators.”[18] In this reading, we take those narrators at their word and engage with them as complex individuals with personal histories, private thoughts, and goals. Whether reading the Book of Mormon as literary fiction or as history, this approach offers readers a more serious examination of the text. Perhaps more importantly, this method helps readers and scholars of the Book of Mormon use the book—in whatever capacity—in ways more sensitive to survivors of trauma.

Potential Difficulties

One difficulty of using a trauma-informed lens is the possibly unanswerable question of whether ancient people experienced trauma in the ways as trauma theory posits today. It appears they certainly had different sensibilities regarding human life and the inevitability of suffering. Pastor James Yansen argues that some language of a trauma hermeneutic, such as a diagnosis of “post-traumatic stress disorder” would be anachronistic for a biblical interpretation. He writes, “Being intentionally self-critical is crucial in applications of insights from trauma studies to biblical texts. It is important to avoid the distinctive danger of ethnocentrism in ‘imposing the Western trauma model’ on non-Western entities and texts.”[19] Certainly, scholars must proceed cautiously in negotiating the interface of modern understandings of trauma theory with ancient texts, particularly as the scientific study of trauma has largely occurred in Western cultures.

However, there is good evidence to argue that trauma and its effects can be observed in scripture. As explained above, the trauma response is a neurological condition that occurs because of a person’s inability to cope with their lived experiences. Broadly speaking, it is a physiological rather than a cultural condition, although cultural context shapes the ways in which trauma is experienced.[20] Trauma specialist Marten deVries has argued convincingly that while trauma and its biological effects are universal, methods of healing are heavily based on cultural values and social support.[21] While trauma has only emerged as a recognized field of study within the last few decades, people have long observed, but been unable to articulate or explain, the markers of trauma. Trauma is not new, even if our language to analyze and understand it is.[22]

Perhaps the best way of exploring whether people in scriptural text experienced trauma is simply to carefully read the text in search of signs of trauma-response behavior in individuals and communities. If individuals seem to experience lasting harm after disaster or if communities show the destructive and identity-forming effects of trauma, we may infer that a trauma hermeneutic is reasonable. As theologian Daniel Smith-Christopher argues, we must ask the question, “Were these events faced by the ancient exiles, or ancient warriors, actually traumatizing for the people involved? Were they really disastrous for them?”[23] This article argues that on an individual and communal scale, the observational answer for the Book of Mormon is in the affirmative.

Individual Trauma: Examples from the Life of Nephi

Individual, or micro, traumas can be found throughout the stories of the Book of Mormon, beginning with Nephi. Many instances of violence and trauma marked Nephi’s life, including threats to his life and the lives of family members, dislocation, food insecurity, physical abuse, and witnessing the abuse of family members. Reading the record of Nephi with a trauma-informed lens means sitting with the hurt and harm of each of these events and pondering how Nephi’s traumas—individually and cumulatively, as they compounded throughout his life course—impacted his health, his worldview, and his ministry across his life. It also involves considering how the individual traumas that Nephi experienced shaped his interactions with others, as a parent and a leader, expanding the impact of these traumas beyond Nephi as his words and behaviors were influenced by his traumatic experiences. His parenting was almost certainly affected by the family violence and traumas he survived, meaning the impact of his individual trauma was passed to subsequent generations via attachment, epigenetic, and behavioral pathways. While we call these more focused or familial events individual traumas, a trauma-informed reading requires that we acknowledge and consider how the trauma experienced by one person (or a few people) ripples outward to impact the lives of many more people, including moving forward in time to affect those not yet born.

Rather than giving a singular interpretation, a trauma hermeneutic illuminates difficult questions for the reader to ponder and themes to explore. We offer a few examples of such questions here and invite the reader to ponder these questions and consider what other questions could be drawn from a trauma-informed reading of Nephi’s life and words.

Nephi is beaten with a rod and an angel intervenes (1 Nephi 3:28–30). Nephi and Sam are abused by their older brothers, Laman and Lemuel. The text indicates that verbal abuse (“many hard words” spoken) escalated to physical abuse, which was severe as the younger brothers were beaten with a rod. Only once the violence escalates to severe physical abuse does an angel appear and intervene, perhaps because Nephi and Sam would have otherwise been killed.

A trauma hermeneutic of this incident leaves the reader to consider how the abuse and the timing of the intervention represents a trauma for Nephi. We are left to ponder how this shaped his life and his understanding of God.

- Does Nephi interpret this trauma to mean that God tolerates or allows some abuse, given the late timing of the intervention? Does this event shape his understanding of what violence God sees as acceptable? Does this impact what he teaches his children about God and violence?

- Does Nephi understand the issue here to be his brothers’ wickedness, rather than their violence? Consequently, does this event shape his belief that as long as a person perpetrating/doing violence is not “wicked” or has faith in God that the violence is acceptable?

Nephi kills Laban (1 Nephi 4:5–18). Nephi enters Jerusalem to obtain the plates of brass from Laban. He finds an unconscious Laban and feels compelled by the Spirit to kill him with his own sword. After some resistance, he kills Laban by decapitation.

This event immediately follows Nephi’s own severe victimization inflicted by his older brothers. He then feels required by the Spirit to step into the role of perpetrator and enact more violence by killing Laban. We are left to ponder how these violent events impacted each other and Nephi.

- How has Nephi’s traumatic experience with his brothers and the angel impacted him as he perpetuates this violence and creates this trauma? How does the late intervention by the angel, along with the command to kill Laban, shape Nephi and his views about how God feels about violence, suffering, and harm for the rest of his life?

Nephi is bound in the wilderness and threatened with death (1 Nephi 7:16–19). Laman and Lemuel bind Nephi with cords and leave him in the wilderness. When Nephi prays and is released from the bounds, he speaks to his brothers again, who are once again enraged and seek to hurt him. Only when the wife, daughters, and son of Ishmael step between Nephi and his angry brothers is the situation diffused.

Nephi watches as others step in the line of violence to save his life and stop the abuse. These women and this boy risk being abused or hurt themselves for Nephi’s sake. Nephi is seeing that the abuse in his family that is targeted at him can hurt and threaten others, including those outside of his family. We are left to wonder how this shapes his view of families and his role in relation to the violence.

- Do these episodes of violence and harm inflicted on him and others cause Nephi to parent his children in a way that ensures they are prepared to respond swiftly and efficiently to threats and violence? How do these traumatic events shape the narratives he passes to his family and children about the Lamanites, which fuel justification for generations of war?

Nephi’s bow breaks and his fatigued and hungry family complain about their suffering (1 Nephi 16:17–22). After many days of travel, Nephi and those in his company stop to rest and find food. Nephi breaks his bow and can no longer hunt. Many in the group—Laman, Lemuel, sons of Ishmael, Lehi, and (likely) their wives and children—complain of their hunger and all that they have suffered in the wilderness since leaving Jerusalem. Nephi is affronted by their complaints and murmuring.

This passage lays out behavior by Nephi that may seem harsh or lacking in empathy. Nephi is impatient and frustrated by the complaints of those in the group when they are tired and hungry and have just lost their means of obtaining food. Readers who have experienced severe hunger or food insecurity may know well the consuming ache of gnawing hunger and exhaustion and the difficulties of not complaining in those circumstances. A trauma-informed reading may help us understand the actions of Nephi here, given the violence and trauma he has already experienced in life, and cause us to consider the ongoing impact of that trauma through Nephi’s actions and worldview.

- How have Nephi’s traumas shaped his response to complaints about hunger and fatigue? Because he has survived worse, is he less patient with those who are suffering under less severe or less abusive conditions? What does this passage tell us about how his individual trauma may have influenced his parenting and governing of the coming generations? Do these experiences represent potential traumas for the younger generations around Nephi?

Once Nephi and the others reach the promised land, the difficult and traumatic events in his life do not end. His life continues to be marked by violence and upheaval with much of his suffering at the hands of his older brothers. His role as a prophet did not exempt him from these abusive and violent experiences. However, these experiences do seem to have left their mark in the form of trauma that shaped his views and the words he recorded as a prophet. To uncritically accept these words of Nephi without a trauma-informed lens is to not only miss enormous context and nuance in the text—it also risks passing on the harm of some of his words, such as when he emphasizes the nonfair skin of the Lamanites and describes them as having “a skin of blackness,” “cursed,” and “loathsome.”[24] This understanding brought on by a trauma hermeneutic is the only way to stop the cycle of harm and interrupt the perpetuation of further harm in our readings and teachings. If we recognize and name the individual trauma woven through Nephi’s life and words, we are able to ensure that Nephi’s hurt and trauma does not cause further damage among us.[25]

Communal Trauma: Examples from the Book of Alma

Trauma does not only function individually; it also has “a social dimension.”[26] Communal trauma occurs when an event such as a war, natural disaster, epidemic, or technological calamity affects an entire society and collective identity. It looks fundamentally different from individual trauma. Although it is made up of a collection of singular experiences, the harm generated by communal trauma is greater than the sum of its parts. “When traumatic violence reigns down upon a whole society, trauma becomes a public disaster. When suffering and loss heaped upon one person is no more than a miniscule moment in the massive destruction of a society and its habitat, violence magnifies its effects in uncountable ways.”[27] Communal trauma creates additional problems for traumatized people by creating or exacerbating disconnection and hindering healing. Three primary effects emerge from communal trauma, all of which may be observed in the Book of Mormon, particularly in the Book of Alma.

Broken-Spiritedness

The first effect is a term coined from refugee studies, called “broken-spiritedness.” If “spirit” is “a sense of connection to self, others, and nature; to the vision and hopes for the future; to God and sources of meaning in life; and to the sacred,”[28] then broken-spiritedness is when a major disaster disrupts or interferes with “sources of meaning and the sacred, challenging the power of religion.”[29] Without sources for meaning-making, a culture that previously shared spiritual narratives of purpose and identity may be caught “mid-mourning,” without the tools to process the trauma and heal from it.[30]

Sociologist Kai Erikson describes an example of broken-spiritedness in the case of Grassy Narrows, which involved the dumping of 20,000 pounds of mercury into the Lake of the Woods region of Ontario by a paper and pulp company between 1962 to 1970. When the dumping came to light in early 1970, the Ojibwa First Nations people who lived and made a living fishing there were devastated. Their environment had been decimated, their major source of income disappeared, and many suffered debilitating health effects from the mercury. The Ojibwa people struggled with a wave of religious and cultural disaffection that the Ojibwa leaders were unable to hold back in the following years. The collective effect of individual traumatic experiences of the flood led to a weakening of the community as broken-spiritedness strained people’s sense of context or meaning in the world.[31]

One possible example of broken-spiritedness in the Book of Mormon is in Alma 45:21–24, when the Nephites were recovering from a particularly bloody war with the Lamanites and Zoramites. The text states that “because of their wars with the Lamanites and the many little dissensions and disturbances which had been among the people, it became expedient that the word of God should be declared among them, yea, and that a regulation should be made throughout the church” (Alma 45:21; emphasis added). The word “because” implies that the impact of violence is to necessitate Helaman and other church leaders to shore up the church. In the wake of the severe trauma of the “work of death” (Alma 44:20), the people began to disassociate from the church. Regardless of their efforts, “dissension” arose, and the people would no longer follow their traditional leaders. Although the text claims that this is because the people grew proud because of riches (Alma 45:24), a trauma hermeneutic would be sensitive to whether this community is suffering from broken-spiritedness following disaster. It might ask the following questions.

- How do the Nephite soldiers who have recently participated in extremely bloody warfare and then “returned and came to their houses and their lands” (Alma 44:23) reintegrate into their communities? Did any of the violence they experienced in war affect their families?

- What were the “little dissensions and disturbances” (Alma 44:21), and were they related to the greater violence? Was this a part of a pattern of violence and a community that was in a crisis of faith?

Helaman repeats the work of establishing a “regulation” in the church following the end of war in Alma 62:44, and again the text attributes the need for it to the violence and contention that has occurred. These two moments in Alma following long-standing bloodshed indicate that the people experienced some degree of broken-spiritedness in the periods following war.

Social Destruction

Similar, but not identical, to broken-spiritedness is when communal trauma prompts social disintegration and “damages the textures of community.”[32] Traumatized communities are not merely a collection of traumatized individuals.[33] The social body, as an organism, sustains damage over time that is difficult to repair. The original trauma, rather than acting as a discrete event, prompts a decrease in trust, intimacy, shared traditions, and communality and an increase in fear, suspicion, and isolation, creating long-term repercussions and a lack of support for healing. As Erikson describes the damages to the social organism of the community: “‘I’ continue to exist, though damaged and maybe even permanently changed. ‘You’ continue to exist, though distant and hard to relate to. But ‘we’ no longer exist as a connected pair or as linked cells in a larger communal body.”[34] The social fabric cannot withstand the compounded stress, and people disconnect and withdraw, creating conditions more likely to result in conflict and perhaps further trauma. Helsel describes this as a “vicious cycle of disconnection in which individual trauma and the erosion of communality [go] hand in hand.”[35]

This “vicious cycle of disconnection” is precisely what we see throughout the Book of Alma, which is essentially a story about a society moving between states of negative peace, fragmentation, and outright war (with some exceptional periods of true peace). It begins in the very first chapter of Alma, in which Nehor kills Gideon[36] and incites a schism with the Nephite nation.[37] In the following chapters, the peoples of the Book of Mormon do not go more than six years without a major battle, with the text describing in striking detail the viciousness of violence and the subsequent mourning.[38]

Although the book claims periods of “continual peace,”[39] in actuality these last only a few years at a time, making them more like ceasefires than a true peace. These stretches of time in between overt violence are where readers can observe patterns of social disconnection. This is most clearly seen in the ruptures within the Nephite church. These take several different forms, but they all share a pattern of social hierarchies that disturb human relationships, decrease cohesion, and increase isolation.

In one example of social disconnection during a period of “peace,” the text describes Alma’s success efforts to “establish the church more fully,”[40] although this claim is compromised by the immediate fracturing into socioeconomic hierarchies. The text says they became “scornful, one towards another, and they began to persecute those that did not believe according to their own will and pleasure.”[41] Even within the church, “there were envyings, and strife, and malice, and persecutions, and pride.”[42] Thus, a social institution meant to function as a unifying and foundational part of Nephite culture is not only failing, but actually acting to alienate and harm people. Clearly, the social fabric is extremely frail.

Reading this period without the context of the wars that immediately preceded and followed it fails to reveal the possible reasons why the social fabric was so weak. It makes it easy to read the text as binary or simplistic, with some people as casually evil. Erikson’s theory of communal trauma puts those people in the context of the violence and disruption they have very recently experienced. Only a few years previously, “tens of thousands” of people died in battle in Nephite land.[43] The composite body sustained a wound that would not heal easily or quickly. Erikson’s description of collective trauma as “a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of communality”[44] can be observed in this society so forcefully dividing itself into antagonistic groups shortly after disaster. The violence and trauma that occurs within the Nephite society, then, is potentially an effect of the recent violence and trauma that has occurred between the Nephites and the Lamanites. As Erikson describes, trauma leads to the social disintegration that then prompts further violence. Questions that arise for readers might include the following.

- How did this social destruction seen in Alma impact the future generations? How could this failing social fabric and lack of a unified “we” shape the relationship people and families had to each other, the church, and God, and what evidence of this may exist in the text?

- The loss of community and connection can breed distrust and less grace in one’s interactions with others. How did this traumatic social disintegration impact the stories the people told about their families and people (e.g., within the Nephite church)? How did it impact the stories and perspectives people believed about their “enemies”?

Scholar Philip Browning Helsel argues that a critical contribution of a trauma hermeneutic to biblical studies is to understand the ways in which violence, collective trauma, and social destruction is cyclical and chronic and how that appears in sacred text.[45] Reading the Book of Mormon through this lens, as a text about the “disruption to the relational fabric of community,”[46] may lend important new insights into how violence has long-term consequences for individuals and societies and how this affects their spiritual health.

Social Construction

Paradoxically, trauma also sometimes functions as a socially constructive force, establishing or strengthening groups that have a shared traumatic experience. Trauma scholar Jeffrey Alexander describes this phenomenon occurring when a collective body accepts a particular trauma narrative and uses it to form a social identity. The narrative does four things: (1) it describes a certain group that has suffered in similar ways and for the same reason; (2) it recounts the hardship endured; (3) it names the agent responsible for the wound; and (4) it petitions those outside of the group for sympathy.[47] The formation of a post-traumatic social construction group identity is not an automatic outcome of collective trauma. “It occurs through a process of representation that brings about a new collective identity.”[48] On the composite level, trauma becomes a powerful social force, integrated into the “communal memory through acts of representation and meaning-making.”[49] This process may play a critical role when a group faces the forces of social destruction described above. When a community faces the stress of collective trauma, creating meaning from an event and renegotiating an identity formed under the experience of that trauma may counteract the forces of social disintegration.[50]

What is most salient in the formation of the identity is the trauma narrative not the factual events of what occurred. Whether or not the community members acted as aggressors or victims, whether or not the community actually underwent certain tragedies, and/or whether or not the named agent was in fact responsible is less important than the story the community tells itself in establishing or reinforcing identity. As biblical scholar David Janzen writes, “From this point of view, trauma is a social construction of meaning.”[51] Alexander describes this story as the “master narrative”: a story or set of stories that hold the identity of a community in place.[52]

Identity formed through collective trauma can be passed down through generations. Citing sociologist Vamik Volkan, Janzen describes how even “shared feelings of powerlessness . . . can help bind a community together, and groups can choose to reawaken these and other feelings associated with the trauma—can deliberately claim this experience, in other words—even generations after the event, in order to portray a current enemy as responsible for past trauma.”[53] In other words, trauma is being passed down not only epigenetically but also narratively and sometimes even voluntarily, as part of a social force to form a cohesive group with an antagonistic relationship toward the agent responsible for the trauma.

The repeating theme of shifting identities, dissenting groups, and new names makes this idea of social construction through trauma interesting to consider throughout the Book of Mormon. One fascinating example of social construction following trauma is that of the Zoramites.

The Zoramites first function as an important part of the Book of Mormon plot in Alma 30, although the text makes a passing reference to them earlier.[54] It is unclear whether the Zoramites in Alma 30 are a stable ethnic group descended from that previous reference or whether these Zoramites are a newly formed dissenting group from the Nephites. It is also unclear whether they are biological descendants of the Zoram who came with Nephi out of Jerusalem or whether they name themselves after their current leader, also named Zoram.[55] However, what is pertinent is that they identify with the story of Zoram, whether or not they factually are biologically related to him. This becomes clear later in the conflict between the Zoramites and the Nephites, when the Zoramites’ leader, Ammoron, attacks Moroni with the words “I am Ammoron, and a descendant of Zoram, whom your fathers pressed and brought out of Jerusalem. And behold now, I am a bold Lamanite.”[56]

These two sentences have a fascinating ethnic and narrative background. Because the record only offers Nephi’s version of events, readers do not know how willingly Zoram went into the wilderness with Lehi’s family. However, even Nephi admits that he used force in the situation.[57] Zoram’s choice between dislocation and death was hardly a choice.[58] The Zoramites, who appear to have lived on the margins of a stratified Nephite society,[59] apparently have a narrative in which their ancestor experienced severe trauma at the hands of Nephi. This version of their origin story, exacerbated by their current state of relative powerlessness in the Nephite/Mulekite society, appears to have strengthened the influence of ethnic identity. In Alma 31, the Zoramites have become Nephite dissenters and removed themselves to the city of Antionum. They construct a new society, including a new government, church, and social order. Others have observed that the Zoramites seem intent on building a nation that is intentionally oppositional to the Nephites, rather than toward ideals of their own.[60] When Alma and his companions disrupt that new (immensely hierarchical) society and attempt to reform it with Nephite teachings, the elite Zoramites are further radicalized toward their Zoramite identity. The remainder of their story within the Book of Mormon is one of extreme violence, as they become virulently anti-Nephite and lead the Lamanite military in attacking the Nephites.[61] Ammoron’s strange declaration that he is “a bold Lamanite” is the final realignment in shifting group identities.

Were the Zoramites simply bad people? A trauma-informed reading reveals a more complex story of this group, in which people inherited a narrative of a traumatic event, claimed the experience, identified an agent responsible for their suffering, and strengthened an identity that might otherwise have become dormant. The violence they perceived as enacted on them—directly through Nephi’s treatment of Zoram and structurally through the hierarchies of Nephite society—generated a trauma response. This does not excuse the violence they commit, but it does better explain it.

A Trauma-Informed Hermeneutic for Survival Literature

Survival literature is “literature produced in the aftermath of a major catastrophe and its accompanying atrocities by survivors of that catastrophe.”[62] The devastation may occur on an individual or collective level. Rev. David Garber draws the analogy of if trauma is the injury, then survival literature is the scar: “the visible trace offered by the survivor that points in the direction of the initial experience.”[63]

One of the most important functions of survival literature is its role in the meaning-making process. One of the primary characteristics of trauma is that it resists integration into the broader narrative of a survivor’s life. It becomes a memory fragment, a shard that continues to cause disruption and disconnection until it can be articulated and processed.[64] Turning a traumatic experience into narrative form and interpreting it to have cause and purpose is not merely a creation of record; it is also a crucial part of re-creating order, agency, and meaning, thus facilitating recovery.[65] In scripture, this narrative has an added layer: it interprets the events in relationship to God. Thus, the meaning-making is interwoven with the speaker’s faith in a divine being who has allowed or even caused disastrous events to happen. In a trauma hermeneutic, then, one purpose of scripture is to “name the suffering experienced by the community and to bring that lived reality before the presence of God.”[66] This work has the potential capacity to help survivors replace harmful memories and thoughts with a narrative that restores a sense of well-being.

In this, however, there lies an important paradox. Survival literary theory “maintains as a cornerstone the unknowability of trauma.”[67] Even while survivors attempt to use words to articulate what happened to them, they will never be fully able to convey the experience. Trauma specialist Cathy Caruth describes this as “speechless terror” or “the incomprehensibility of pain.”[68] Turley effectively notes how the narrative of Alma the Younger’s experience in Ammonihah, in which he witnessed the brutal deaths of women and children by fire, points to Alma’s trauma in the experience. The chief judge of Ammonihah questions Alma and Amulek and physically abuses them while demanding a response, yet they remain silent. “Silence can be a rational choice, but it can also be a response to shocking trauma. . . . What a person’s eyes saw or ears heard or body felt is recorded in the brain, but . . . [the memories] are scattered and recorded in fragments.”[69] While the text may strive to bear witness and “to respond so that horror and violence do not have the last word,” terrible suffering is often beyond human language.[70]

This limitation of language helps explain some of the signs of survival literature: it is often told in fragments, with a heavy use of imagery, symbols, wordplay, and “multiple levels of meaning.”[71] It uses the world of analogy, poetry, and repetition because of the struggle to convey disaster in a straightforward manner. Survival literature does not merely “report facts but, in [a] different way, encounter—and make us encounter—strangeness.”[72] Because the right words do not exist, the text is not straightforwardly referential. Importantly, this does not make survival literature unreliable or useless for historians. Instead, according to Caruth, those who wish to understand “must permit ‘history to arise where immediate understanding may not.’”[73] This may change the framework for those reading scripture: rather than interpreting it as a historical account, a trauma hermeneutic sees holy text as an interpretive account. It is “art more than history, or better, art intervening in history.”[74]

Where might readers see signals of survival literature in the Book of Mormon? Clearly, the Book of Mormon does not contain any passages comparable to Lamentations, Jeremiah, or Ezekiel, with their poems and verses about exile and genocide. The Book of Mormon seems to be intended more as a record than as a lament. Yet some verses seem to qualify as survival literature in their use of imagery and metaphor to describe the suffering and struggle the author has experienced:

O then, if I have seen so great things, if the Lord in his condescension unto the children of men hath visited men in so much mercy, why should my heart weep and my soul linger in the valley of sorrow, and my flesh waste away, and my strength slacken, because of mine afflictions? (2 Nephi 4:26)

I conclude this record, declaring that I have written according to the best of my knowledge, by saying that the time passed away with us, and also our lives passed away like as it were unto us a dream, we being a lonesome and a solemn people, wanderers, cast out from Jerusalem, born in tribulation, in a wilderness and hated of our brethren, which caused wars and contentions; wherefore, we did mourn out our days. (Jacob 7:26)[75]

And it came to pass that there was thick darkness upon all the face of the land, insomuch that the inhabitants thereof who had not fallen could feel the vapor of darkness. And there could be no light, because of the darkness, neither candles, neither torches; neither could there be fire kindled with their fine and exceedingly dry wood, so that there could not be any light at all. (3 Nephi 8:20–21)

These are three of many examples that a trauma hermeneutic would be sensitive toward, understanding that the imagery used might be intended to convey a feeling or experience rather than a factual event. A trauma-informed lens centers how the author uses text to process their own trauma and narrates God into that experience. It seeks to connect with the concerns of the survivor and look for multiple meanings of the text.

Trauma Hermeneutic and Theodicy

A trauma hermeneutic notices the ways in which people use scriptural text to make sense of the world and God’s role within it. It is common within the Bible and the Book of Mormon for the text to blame death, famine, loss in battle, plague, and natural disasters as a curse from God. As readers, we are left to ponder: is God in fact the vengeful perpetrator of destructive wrath? As Alexander notes, “When causality is assigned in the religious arena, it raises issues of theodicy.”[76] When trauma happens, any survivor must confront the question of why it occurred and who is responsible. In the case of a person or community of faith, that question has the added complexity of God’s culpability. Survivors might wonder: Did God let it happen? Was God unable to stop it? Was God too weak or did God simply not care? If I cannot count on God for protection, then when might it happen again? Frequently, scriptural text seems to evade these questions through claiming the will of God and the sinful actions of the victim or victims as responsible for the disaster. By blaming God for destruction, the narrator paradoxically reclaims agency and power. For example, the book of Ezekiel insists that the Babylonians’ triumph over Israel was due to Israel’s sinfulness and Yahweh’s desire for punishment[77] rather than the Babylonian’s superior military strength or faithfulness. Theologian Brad Kelle argues that this simultaneously rejects the Babylonians’ claim to power over Israel and rhetorically identifies Israel as God’s people in need of repentance rather than as a conquered society.[78] This way of making sense of trauma is not unusual for trauma survivors. Those who endure horrific events sometimes blame themselves in order to restore some sense of order out of a chaotic universe. It can feel easier to be guilty than to be helpless.[79] As scholars Elizabeth Boase and Christopher Frechette argue, “An overwhelmingly threatening event often prompts interpretations of the cause of the experience in a way that places irrational blame on the self. Doing so serves as a survival mechanism; by providing an explanation and asserting a sense of control, blaming the self helps a person to confront the imminent threat of overwhelming chaos.”[80]

In this way, scriptural survival literature constructs a worldview that gives hope and order to a society, although it comes with costs, including blaming victims for the disasters and violence they have suffered.[81] While restoring mental balance and reducing feelings of chaos, this may increase emotional anguish and possibly hinder the healing process as people struggle with shame and guilt for bringing their difficulties upon themselves. It also can create a crisis of theodicy. Boase points out that this crisis may take two forms: the belief that God is responsible for the trauma and God’s apparent silence as it occurs.[82] Thus, “Yahweh is both an oppressive presence . . . but is also silently absent.”[83] Survival literature may help a community in crisis but create other harm in the process. A trauma hermeneutic is aware of how the narratives derived in a post-traumatic setting have complex effects.

The Book of Mormon offers many possible examples of authors and characters attempting to make sense of the horrific by blaming victims’ sinfulness and/or God’s will. Two cases include:

- The text blaming Limhi’s people for their own suffering in Mosiah 21. The multiple military defeats they endure and their situation of effective slavery under the Lamanites is attributed to God’s will[84] rather than the superior strength or numbers of the Lamanites. The text also claims that these traumatic events happened in order to pressure the people into repentance but that after they “did humble themselves even in the depth of humility” that “the Lord was slow to hear their cry because of their iniquities.”[85]

- When the Nephite dissenters and Lamanites successfully attack the land of Zarahemla, the text explains the Nephites’ defeat as directly caused by the moral failings of the Nephites: “Now this great loss of the Nephites, and the great slaughter which was among them, would not have happened had it not been for their wickedness and their abomination which was among them; yea, and it was among those also who professed to belong to the church of God. . . . And because of this their great wickedness, and their boastings in their own strength, they were left in their own strength; therefore they did not prosper, but were afflicted and smitten, and driven before the Lamanites. . . . And it came to pass that they did repent and inasmuch as they did repent they did begin to prosper.”[86]

Scriptural claims that God not only sanctioned slavery and death in order to force repentance but then did not listen to prayers asking for help because of past transgressions are theologically burdensome for readers who have themselves suffered extreme violence or whose ancestors did. Those who inherited the effects of trauma due to a family history of slavery might question whether God truly approves of such methods in order to compel obedience. Yet a trauma-informed reading understands that even those who live through the original trauma and create survival literature might attempt to find order in chaos by choosing a narrative in which God has chosen suffering for them. Doing so allows a powerless victim to “take the initiative and act effectively”[87]—they can contain their misfortunes through making moral choices.

A trauma-informed hermeneutic comprehends the complexity of trauma literature and the ways in which it subtly appears within text. Indirect language, metaphor, and poetry might hint at pain hidden just below the stated idea or narrative. Theological explanations for suffering should be taken as the author’s attempt to make sense of the senseless rather than an authoritative description of divine will. As Boase and Frechette write, “To grasp the ways in which language can represent trauma opens up new avenues for understanding violent imagery, especially violent depictions of God, and shed light on organizing principles.”[88] To read the Book of Mormon in this way is an opportunity to understand how people who survived extreme trauma constructed theology.

Application of a Trauma-Informed Lens

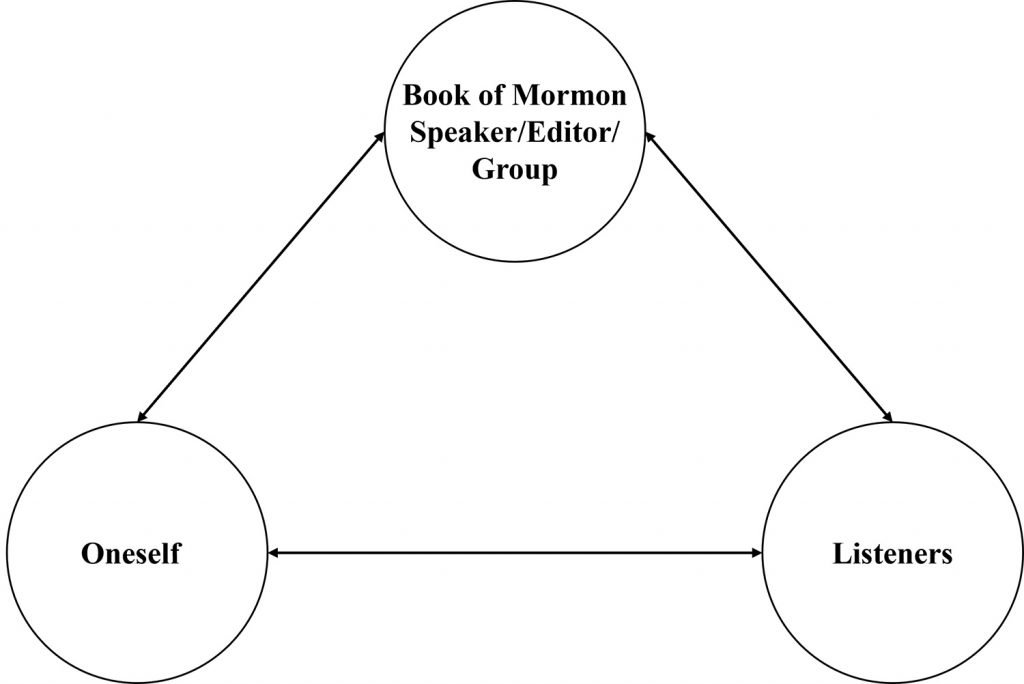

A trauma-informed reading of the Book of Mormon requires an additional step beyond our interpretation of the text. In fact, the trauma-informed lens explicitly pushes us to not only consider and acknowledge the trauma contained in the text of the scripture and the voices (or missing voices) therein but to also examine how our own trauma shapes our reading. Additionally, as there is a long-standing tradition in the in the Church of Jesus of Christ of Latter-day Saints to teach the stories and sermons of the Book of Mormon over the pulpit and in church classroom groups, it is also crucial to be sensitive to and acknowledge the trauma of those sitting in these rooms and how these interpretations in our sermons and lessons impact them. As such, to approach the Book of Mormon with a trauma-informed lens in the twenty-first century, we are required to consider at least three loci of trauma: the speaker (or editor or group) in the Book of Mormon, our own, and those who hear us discuss the text (figure 1).

To examine the trauma present—whether acknowledged or not—in the text of the Book of Mormon without consideration of trauma we, as the reader of the text, may carry severely limits and distorts the trauma hermeneutic applied. For example, imagine yourself as a reader of the Book of Mormon who has experienced severe family violence perpetrated by a sibling encountering Nephi’s words of his brothers beating him with a rod (1 Nephi 3).[89] If that reader seeks to consider how trauma has shaped the perspective and words of Nephi without considering their own response to this shared traumatic event, they will likely be unable to move deeply and meaningfully through a trauma-informed reading, as they are not recognizing how their own trauma is shaping the questions they are asking of or assumptions they are making in the text. They may struggle to relate to the response Nephi has to this event if it differs from their own response to the violence in their lives. Alternatively, they may feel anger that an angel was sent to intervene to stop this beating in Nephi’s life but that they did not receive this form of divine intervention. Any of these responses are valid and arise from their own trauma impacting how they engage with the trauma in the text. By acknowledging, rather than repressing, the violence and trauma in their past, the reader may be able to step closer to the text, allowing them to engage in a trauma-informed reading that is more vulnerable and that brings more empathy for Nephi and the traumas in his story while also giving themselves space for their own traumatic history. This allows the reader to explicitly acknowledge that, though their trauma responses may differ from Nephi’s or their path with God may diverge from his, there is beauty and value in considering his words through the lens of trauma while giving grace for how their own perspective has been shaped by trauma.

Finally, given the tradition to discuss the stories of the Book of Mormon over the pulpit and in church classes, it is crucial that any exploration of the words or lives in the Book of Mormon respects the unseen and unspoken traumas of those in the congregation or class. A teacher or speaker seeking to apply a trauma hermeneutic to the stories of Alma preaching in Ammonihah (Alma 14) or to the abduction of Lamanite daughters by the priests of Noah (Mosiah 12) must carefully consider the traumas that those listening to their lesson, sermon, or comment may have. There may be listeners who have experienced the loss of a parent or loved one by murder or fire (Alma 14:8) or experienced sexual assault (Mosiah 12:5), which will shape the way they respond to these tragic and traumatic stories. To apply a trauma-informed lens thus requires that all discussion—by the teacher and by others in the room—of these events from the Book of Mormon is sensitive to the trauma that others in the room may carry. Rambo explains this idea as making space for trauma and its effect on faith stating, “Marking this space is not simply a way of advocating for persons who are unaccounted for. Instead, attempting to map the experiences of trauma comes from my conviction that our lives are inextricably bound together. Given what we know about the historical dimensions of trauma, no one remains untouched by overwhelming violence. Trauma becomes not simply a detour on the map of faith but, rather a significant reworking of the entire map.”[90] To make this space when exploring these stories in Alma 14 or Mosiah 12, a teacher or class member may want to approach the text to consider the traumatic implications for Alma of watching the murder by fire of women and children in Ammonihah; before they speak, they must thoughtfully reflect on what their words imply to those listening who may carry trauma. Do their insights into the text honor and respect those hurts? Or do they downplay the harm inherent in the events?[91] Application of a trauma-informed lens that is sensitive to the trauma in the room can provide religious discussions that empower listeners rather than further traumatize them. Likewise, approaching the trauma in the text while holding space for our own trauma allows us to find more humanity and connection in the traumatic and human stories contained there. Rather than causing further harm to ourselves and others via a harsh or critical reading of the text that ignores the trauma in the stories and the traumas of today, a trauma-informed hermeneutic can create a nurturing space that allows for readings of the Book of Mormon that can face and, potentially, heal the trauma we carry in ourselves or that listeners carry.

Conclusion

The benefits of using a trauma hermeneutic are clear. Scripture has long served as a narration of individuals’ and communities’ understanding of their relationship to God. In the wake of disaster, a trauma hermeneutic perceives that the readers’ understanding of this narration is incomplete without an appreciation for the ways in which “trauma erodes aspects of identity and solidarity necessary for well-being.”[92] Stories of intense suffering, especially those attributed to divine punishment, have consistently raised questions of theodicy. Sections of scripture depicting God as destructive, abusive, and wrathful frequently seem inconsistent with those describing God as loving and merciful. A trauma-informed reading of scripture understands the human will to make order out of disorder and reassert control over chaos.[93] By attributing suffering to sin and divine will, a small amount of order is reinstated in the aftermath of catastrophe.

Second, a trauma hermeneutic allows for alternative interpretations of the text, including the recognition of “symbolic representations corresponding to actual violence”[94] and the importance of “fragmented and impressionistic images” that defy a “plain-sense account of events.”[95] Strange imagery and language may indirectly point readers toward experiences of terror and loss.[96]

Third, a trauma hermeneutic complements both historical and literary approaches to scripture. The field of comparative literature has helped shape the field of trauma biblical studies through the analysis of the “survival literature” produced during the atrocities of the twentieth century.[97] The investigation of narrative, symbolism, poetry, and testimony can all be deepened through an understanding of trauma. Additionally, historical scholars can benefit from a better awareness of the realities of the short- and long-term effects of traumatic violence on individuals and communities. This builds upon, rather than contradicts, historical-critical models of reading.[98]

Fourth, those who have survived trauma often struggle to communicate their experiences to others effectively. Without understanding trauma, readers may shy away from certain passages or characters because they seem distasteful, frustrating, or incomprehensible. One of the most important goals of trauma studies is “to ask how we can listen to trauma beyond its pathology for the truth that it tells us.”[99] Whether readers enjoy sections of scripture about suffering and the people involved in them may be moot. Instead, looking through the lens of trauma could help readers understand even if they do not like or enjoy scripture. A trauma-informed biblical hermeneutic supports an interrogation of scriptural characters and writers in which readers transform the question “What’s wrong with you?” into “What happened to you?”[100] This shift in thinking crosses cultural boundaries and helps increase empathy and compassion for subjects that may otherwise seem foreign.

Finally, the use of a trauma hermeneutic may make scripture relevant for readers today and help transform disturbing books of scripture into healing ones. Given current world events, many students of holy texts are searching for answers to questions about theodicy, human suffering, and how people narrate God into their lives during periods of darkness. It also gives a particular set of tools for reading scripture for those who have experienced trauma. One Old Testament professor has described how using a trauma-informed lens has transformed the dynamic in her seminary classes: “As the class unfolded and the student’s stories came out, I recognized something else about Jeremiah that before had been only an unarticulated hunch. The book did more than give voice to the afflicted. It was and is a most effective instrument of survival and healing.”[101] This is, effectively, expanding the role of scripture, giving it an additional and critical function in pastoral care.

To the degree in which the Book of Mormon functions as survival literature, its coherence does not depend on a single narrative thread of trauma or a single identifiable point in which the record attempts to make sense of the trauma experienced. Throughout the book, people within the Book of Mormon endure a wide variety of individual and collective traumatic events. As is typical, their responses vary, with some people/groups reacting with further violence while others construct a theology that explains and reorganizes the disruption. Violence, suffering, trauma, and trauma responses run throughout this book of scripture. While the field of biblical studies has already begun a serious study of how to use a trauma hermeneutic, the use of this method is rarely used for the Book of Mormon. The increasing understanding that trauma is, to varying degrees, a universal part of the human condition makes this a compelling field of greater study. This article is clearly not an exhaustive review of all the trauma found in the text but rather an invitation to all readers to use this lens. Further work in this area should be cross-disciplinary, including the work in biblical studies, refugee studies, psychology, literary studies, and sociology. Most particularly, it should focus on the perspectives of those who have suffered most deeply from trauma and who stand on the margins of society. Their voices are critical in this work.

[1] Nicholas Collura, “When Patients Talk Politics: Opportunities for Recontextualizing Ministerial Theory and Practice,” Pastoral Psychology 71 (2022): 556, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-022-01013-3.

[2] See, for example, Elizabeth Boase and Christopher G. Frechette, Bible Through the Lens of Trauma (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2016); David M. Carr, Holy Resilience: The Bible’s Traumatic Origins (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014); and Kathleen M. O’Connor, Jeremiah: Pain and Promise (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2011). A review of the study of the Bible and trauma theory can be found in David G. Garber Jr.’s “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” Currents in Biblical Research 14, no. 1 (2015): 24–44.

[3] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 25.

[4] James W. S. Yansen Jr., Daughter Zion’s Trauma: A Trauma-Informed Reading of the Book of Lamentations (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2019), 13.

[5] Elizabeth Boase and Christopher G. Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma’ as a Useful Lens for Biblical Interpretation,” in Bible Through the Lens of Trauma, 13.

[6] Deidre Nicole Green, Jacob: A Brief Theological Introduction (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2020); Kylie Nielson Turley, Alma 1–29: A Brief Theological Introduction (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2020); and “Alma’s Hell: Repentance, Consequence, and the Lake of Fire and Brimstone,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 28, no. 1 (2019).

[7] Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US), Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 57 (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [US], 2014), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/.

[8] NHS Scotland, “NES Trauma Informed—What Is Meant by Trauma?,” accessed Aug. 15, 2022, available at https://transformingpsychologicaltrauma.scot/resources/understanding-trauma/.

[9] Daniel Gutierrez and Andrea Gutierrez, “Developing a Trauma-Informed Lens in the College Classroom And Empowering Students through Building Positive Relationships,” Contemporary Issues in Education Research 12, no. 1 (2019):13, https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v12i1.10258.

[10] Gutierrez and Gutierrez, “Developing a Trauma-Informed Lens,” 13–14.

[11] Natan P. F. Kellermann “Epigenetic Transmission of Holocaust Trauma: Can Nightmares Be Inherited?” Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 50, no. 1 (2013) 33–39; Natan P. F. Kellermann, “Epigenetic Transgenerational Transmission of Holocaust Trauma: A Review,” Oct. 12, 2015, https://peterfelix.tripod.com/home/epigeneticttt_2015.pdf.

[12] Laurence J. Kirmayer, Robert Lemelson, and Mark Barad, “Introduction: Inscribing Trauma in Culture, Brain, and Body,” in Understanding Trauma: Integrating Biological, Clinical, and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Laurence J. Kirmayer, Robert Lemelson, and Mark Barad (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 10.

[13] Kirmayer, Lemelson, and Barad, “Introduction: Inscribing Trauma”; Ami Harbin, “Resilience and Group-Based Harm,” International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 12, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.3138/ijfab.12.1.02.

[14] NHS Scotland, “NES Trauma Informed.”

[15] “Viewing Your Work through a Trauma-Informed Lens,” Relias, modified Dec. 27, 2018, accessed June 6, 2022, https://www.relias.com/blog/viewing-your-work-through-a-trauma-informed-lens.

[16] Kirmayer, Lemelson, and Barad. “Introduction: Inscribing Trauma,” 4.

[17] Alma 58:40.

[18] Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), xv.

[19] Yansen, Daughter Zion’s Trauma, 9.

[20] Yansen, Daughter Zion’s Trauma, 7.

[21] Marten W. deVries, “Trauma in Cultural Perspective,” in Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society, edited by Bessel A. van der Kolk, Alexander C. McFarlane, and Lars Weisaeth (New York: Guilford Press, 1996), 398–413.

[22] Shelley Rambo, Spirit and Trauma: A Theology of Remaining (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 3.

[23] Daniel L. Smith-Christopher, “Reading War and Trauma: Suggestions Toward a Social-Psychological Exegesis of Exile and War in Biblical Texts,” in Interpreting Exile: Displacement and Deportation in Biblical and Modern Contexts, edited by Brad Kelle (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2011), 264.

[24] 2 Nephi 5:21–25.

[25] Fatimah Salleh and Margaret Olsen Hemming, The Book of Mormon for the Least of These (Salt Lake City, Utah: BCC Press), 1:66–68.

[26] Kai Erikson, “Notes on Trauma and Community,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, edited by Cathy Caruth (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 185.

[27] O’Connor, Jeremiah, 3.

[28] John P. Wilson, “The Broken Spirit: Posttraumatic Damage to the Self,” in Broken Spirits: The Treatment of Traumatized Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and War and Torture Victims, by John P. Wilson and Boris Droždek (New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2005), 112.

[29] Philip Browning Helsel, “Shared Pleasure to Soothe the Broken Spirit: Collective Trauma and Qoheleth,” in Bible Through the Lens of Trauma, 85.

[30] Helsel, “Shared Pleasure,” 85.

[31] Kai T. Erikson, A New Species of Trouble: Explorations in Disaster, Trauma, and Community (New York: Norton, 1994), 27–57.

[32] Erikson, “Notes on Trauma and Community,” 187.

[33] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 28.

[34] Erikson, “Notes on Trauma and Community,” 233.

[35] Helsel, “Shared Pleasure,” 87.

[36] Alma 1:9.

[37] Alma 1:16.

[38] For example, Alma 3:26, 16:9, 30:2, 4:2, 28:4, and 28:5–6.

[39] Alma 4:5.

[40] Alma 4:4.

[41] Alma 4:8.

[42] Alma 4:9.

[43] Alma 3:26.

[44] Erikson, A New Species of Trouble, 233.

[45] Helsel, “Shared Pleasure,” 100.

[46] Helsel, “Shared Pleasure,” 100.

[47] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 8.

[48] Elizabeth Boase, “Fragmented Voices: Collective Identity and Traumatization in Lamentations,” in Bible Through the Lense of Trauma, 54.

[49] Boase, “Fragmented Voices,” 55.

[50] David Janzen, “Claimed and Unclaimed Experience: Problematic Readings of Trauma in the Hebrew Bible,” Biblical Interpretation 27 (2019): 171.

[51] Janzen, “Claimed and Unclaimed Experience,” 170.

[52] Alexander, Trauma: A Social Theory (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), 17.

[53] Janzen, “Claimed and Unclaimed Experience,” 170.

[54] Such as Jacob 1:13.

[55] Alma 31:1.

[56] Alma 54:23.

[57] 1 Nephi 4:31.

[58] Salleh and Olsen Hemming, The Book of Mormon for the Least of These, 1:90.

[59] Sherri Mills Benson, “The Zoramite Separation: A Sociological Perspective,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005): 78–79.

[60] Benson, “The Zoramite Separation,” 84.

[61] Alma 43:44.

[62] Tod Linafelt, Surviving Lamentations: Catastrophe, Lament, and Protest in the Afterlife of a Biblical Book (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 18.

[63] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 28.

[64] Brad E. Kelle, “Dealing with the Trauma of Defeat: The Rhetoric of the Devastation and Rejuvenation of Nature in Ezekiel,” Journal of Bible Literature 128, no. 3 (2009): 483.

[65] Margaret S. Odell, “Fragments of Traumatic Memory: Ṣalmȇ zākār and Child Sacrifice in Ezekiel 16:15–22,” in Bible Through the Lens of Trauma, 112; O’Connor, Jeremiah, 5; Yansen, Daughter Zion, 14; Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 11.

[66] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 31.

[67] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 11.

[68] Bessel A. van der Kolk and Onno van der Hart, “The Intrusive Past: The Flexibility of Memory and the Engraving of Trauma,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, 172.

[69] Turley, Alma 1–29, 89.

[70] Ruth Poser, “No Words: The Book of Ezekiel as Trauma Literature and a Response to Exile,” in Bible Through the Lens of Trauma, 39.

[71] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 26.

[72] Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History (Milton Park, England: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 7.

[73] Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 11.

[74] O’Connor, Jeremiah, 5.

[75] Deidre Nicole Green characterizes Jacob’s description of the state of his people in this passage as “mass disassociation, or a dreamlike trance that distances people from a reality that would otherwise be too overwhelming to cope with, which is indicative of traumatic stress lived out on a grand scale.” Green, Jacob, 113.

[76] Alexander, Trauma: A Social Theory, 19.

[77] For example, Ezekiel 6:1–4; 12:17–20; 15:8; 33:28–29; 38:21–23.

[78] Kelle, “Dealing with the Trauma of Defeat,” 489.

[79] Poser, “No Words,” 36.

[80] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 5–6.

[81] Janzen, “Claimed and Unclaimed Experience,” 169.

[82] Elizabeth Boase, “Constructing Meaning in the Face of Suffering: Theodicy in Lamentations,” Vetus Testamentum 58 (2008): 456.

[83] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 31.

[84] Mosiah 21:4.

[85] Mosiah 21:14–15.

[86] Helaman 5:4:11–15.

[87] Poser, “No Words,” 36.

[88] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 16.

[89] Certainly, some of you will not need to imagine such a circumstance, as you have found yourself in that position and experienced this form of family violence in your life. We are heartbroken and sorry this happened to you and are glad you are still here today.

[90] Rambo, Spirit and Trauma, 9.

[91] For instance, do they dismiss or minimize the loss of innocent lives in Alma 14:8 because of the promise of heaven for those victims and instead focus on the trauma Alma experienced by viewing such an event? Or are they careful to ensure that those listening will know that such a tragic loss of life and instance of community violence is painful and worthy of being mourned?

[92] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 15.

[93] Boase, “Fragmented Voices,” 61–62.

[94] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 16–17; though it is worth noting that “actual” violence is not a prerequisite for trauma or applying a trauma hermeneutic, nor is it reasonable to require the text to accurately represent a potentially violent event to make this hermeneutic applicable.

[95] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 13–14.

[96] Kelle, “Dealing with the Trauma of Defeat,” 482.

[97] Garber, “Trauma Theory and Biblical Studies,” 26.

[98] Boase and Frechette, “Defining ‘Trauma,’” 13.

[99] Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, viii.

[100] Caralie Focht, “The Joseph Story: A Trauma-Informed Biblical Hermeneutic for Pastoral Care Providers,” Pastoral Psychology 69 (2020): 210.

[101] O’Connor, Jeremiah, 5

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue