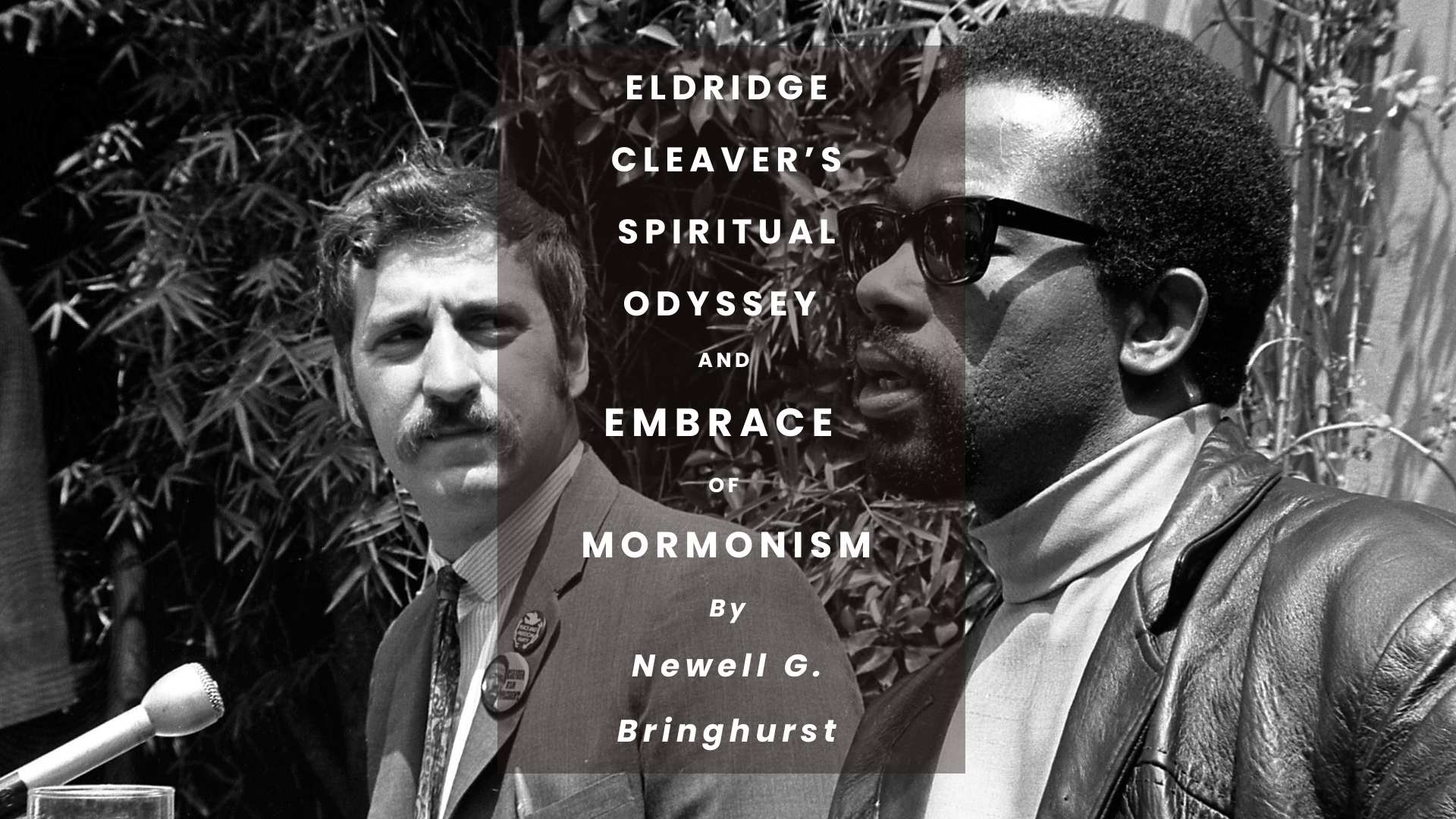

Articles/Essays – Volume 57, No. 2

Eldridge Cleaver’s Spiritual Odyssey and Embrace of Mormonism

Eldridge Cleaver, one-time Black Panther, author of the critically acclaimed best-selling memoir Soul on Ice, and notorious fugitive from justice, was the most famous African American to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints immediately following the 1978 Black Revelation.[1] Cleaver’s baptism took place in December 1983, some three years after his initial contact with the Church. He remained a member of record up to the time of his death on May 1, 1998.[2]

Cleaver’s involvement with Mormonism has received minimal attention in three recent biographies. Kathleen Rout’s Eldridge Cleaver dismisses the one-time Black Panther’s conversion to Mormonism as simply “a complete rejection of a positive black identity.”[3] Justin Gifford, through the pages of Revolution or Death: The Life of Eldridge Cleaver, likewise downplays Cleaver’s so-called “dabbling in Mormonism” although concedes that his conversion “shocked the world.”[4] Finally, Target Zero: Eldridge Cleaver a Life in Writing, edited by Cleaver’s one-time wife, Kathleen, makes no mention whatsoever of his Mormon interlude.[5]

This article seeks to redress such omissions and misperceptions, arguing that Cleaver’s involvement with the Church represents an important phase in the one-time Black militant’s lifelong odyssey as a religious seeker. Much of this story is drawn from an unpublished autobiography Cleaver penned in the wake of his contact with Mormonism and from interviews conducted with Latter-day Saints who knew and interacted with the former Black Panther.[6]

Born in 1935 in Wabasika, Arkansas, LeRoy Eldridge Cleaver was brought up Baptist by his devoutly religious mother. As an adolescent, he converted to Catholicism. Following that he became a militant Black Muslim during his lengthy twelve years of incarceration in a series of California prisons. After his 1975 return to the United States, following a six-year exile abroad, Cleaver proclaimed himself a born-again Christian, involving himself in a number of different Christian groups and causes. He also tried, with limited success, to establish his own Eldridge Cleaver Crusades and later his own congregation, the Third Cross of the Holy Ghost. He attempted to create his own religion, Christlam—a hybrid body of beliefs drawn from Christianity and Islam.[7] Cleaver subsequently involved himself with Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church through his support of Project Volunteer.[8] In sum, as Cleaver himself recalled: “I like to study religion. . . . I have been a Moonie, a Black Muslim, a Catholic, a Baptist, a Jehovah’s Witness, a Seventh-day Adventist. . . . I guess that’s all.”[9]

Cleaver’s initial interest in Mormonism came in the late 1970s.[10] His wife, Kathleen, having attended a Bible study class in which her group had been studying the book of Hebrews, asked her husband “about Melchizedek, a man without a father, without mother, neither beginning of days or end of life, made like unto the Son of God abiding in the priesthood continually.” Kathleen’s query prompted Eldridge to read the whole book of Hebrews noting that “somehow, I knew this was something very important. I also felt there was something special about [Kathleen] bringing this to my attention,” adding “there was a spiritual quality about this experience.” Eldridge asked his own Bible teacher “what he knew about Melchizedek,” who responded by becoming “very upset” and “very quickly changed the subject.” In response, Cleaver “started bugging everybody,” asking, ‘What about Melchizedek?’” “Whenever, I asked about Melchizedek” while traveling about speaking at various “churches and theological seminaries the response was negative. I couldn’t figure out what was going on.”[11]

Ultimately, Cleaver came across a book on communal architecture, containing a drawing of the interior of Kirtland Temple, “showing two podiums, one for the Aaronic Priesthood and one for the Melchizedek Priesthood.” “‘What is this?’ I said, out loud. The Mormons know something about Melchizedek.” This prompted Cleaver to learn more. He initially contemplated attending a church service at an LDS ward house near his home in Menlo Park, but he held back. As he later recalled, “I had heard many things about the Mormons. Like how they didn’t want black people in their church. I was afraid they might not let me in, and I would . . . get my feelings hurt.”[12] All of this occurred in 1980.

In September 1980, Cleaver encountered Carl Loeber, a former associate from his days as a radical activist, who had recently joined the LDS Church. Loeber had served as Cleaver’s campaign manager during his 1968 campaign for president on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket.[13] As Cleaver jokingly recalled: “I didn’t recognize him because he was so clean shaven, he had a short, neat haircut, and was wearing a suit. The last time I saw him he was so greasy; you’d need ice prongs to grab a hold of him.” Loeber, in describing his involvement with the Church, declared that he had held the Melchizedek Priesthood “for about ten years.” Immediately, Cleaver “started asking all kinds of questions about Melchizedek,” prompting Loeber to reply, simply, “I know some young men who can answer all your questions.”[14]

Thus began the three-year process leading to Cleaver’s ultimate baptism into the Church. Initially, Cleaver met with the stake missionaries in the home of Dennis and Sonja Peterson in Cupertino. At the time, Peterson was bishop of the San Jose Sixth Ward and later president of the San Jose Stake. His wife, Sonja, was the niece of future LDS Church President Ezra Taft Benson. Cleaver’s interest in Mormonism caught the immediate attention of high LDS Church officials, specifically President Benson himself, who inquired directly with the Petersons concerning the extent of Cleaver’s interest in the Church.[15]

Cleaver met privately with Paul H. Dunn, a member of the First Council of the Seventy and regional administrator for California. Dunn, like Benson, carefully assessed the former Black Panther’s desire to join the Church. But as Cleaver recalled, Dunn “would not allow me to get baptized” despite an immediate desire to join. The reason was because “I was still on probation. [Dunn] felt I should clear up my differences with the law before joining the Church.”[16]

Through Carl Loeber, Cleaver met another prominent Latter-day Saint, W. Cleon Skousen, with whom he developed a close relationship. Skousen, a Brigham Young University (BYU) professor of religion, was the founder/president of the Freeman Institute—a conservative, anticommunist political education organization.[17] The two initially met at a “Know Your Religion” event at which Skousen was the featured speaker. As Cleaver recalled, “I was overwhelmed with the words of Dr. Skousen. From my own political background, and my experiences in the communist countries, I knew he was telling the truth. I was relieved to hear so much sound thinking from an anti-communist.” Taking note of Skousen’s central argument that the LDS Church stood as a bulwark against communism, Cleaver further praised what he had to say: “Hearing him speak about the Gospel and politics at the same time really made sense to me. I believe the world could not be saved without the Gospel, but it was communism, a political force, that was fighting God and the spreading of the Gospel more than any other single force.” Cleaver then concluded, characterizing Skousen, “a fanatic, just like me, fighting for the gospel, while struggling for freedom and America.”[18] Skousen, taking note of Cleaver’s like-minded beliefs and rhetorical skills, signed him on as a regular speaker for the Freeman Institute. All of this, in turn, further facilitated Cleaver’s desire to become a Latter-day Saint.

Meanwhile, Cleaver continued to meet and interact with Dennis and Sonja Peterson, developing a close congenial relationship, ultimately becoming good friends. As Cleaver recalled, Peterson, a biology professor at De Anza Community College, “had a beautiful way of sharing the gospel. . . . I was very impressed to hear the gospel taught by a man who was also a scientist.”[19] Cleaver, along with Kathleen and their two young children, son Maceo and daughter Joju, became frequent guests in the Peterson home, invited to dinners and interacting socially, with their young children becoming playmates. Sonja Peterson fondly recalls Eldridge as “light, kind, and soft-spoken,” further characterizing both Eldridge and Kathleen as “impressive both in demeanor and intellect.” Eldridge was “extremely proud” of his children as well as his wife, Sonja further recalled. But at the same time, Kathleen, in contrast to her husband, “never indicated any interest, whatsoever, in the Church.”[20]

Kathleen, in fact, left Eldridge in September 1981, accompanied by their two children, moving to New Haven, Connecticut, to attend Yale University on a scholarship. Eldridge was unable to accompany them, given the terms of his probation, and thus extremely reluctant to see them leave. Although the couple put a good face on their separation, the marriage had been turbulent, allegedly marred by infidelity and abusive behavior on the part of Eldridge.[21] Kathleen recalled “the tremendous strains” on their marriage during this period, adding, “We grew distant from each other, no longer sharing the same aspirations and beliefs.” Being without his wife and children proved extremely difficult for Eldridge, given that “he adored his children and his awareness of life’s spiritual dimension was stimulated as he watched them grow up.”[22] Eldridge repeatedly tried to renew Kathleen’s interest in the Church during his visits to New Haven, “possibly delaying his baptism in the hopes that she would have a change of heart.”[23]

Following Kathleen’s departure, Eldridge, finding himself without a place to live, took up temporary residence with Lee Senior, a mutual friend of both Cleaver and Carl Loeber. Like Loeber, Senior was an active, practicing Latter-day Saint. Senior provided Cleaver short-term employment as a tree trimmer with his Blue Ox Tree Company. At the same time, Lee, along with his brother John, acting as informal missionaries, further instructed Cleaver on Mormon doctrine and practice.[24]

Concurrently, Cleaver “started going to church all the time,” initially attending with Carl Loeber at the San Jose Sixth Ward in Cupertino. Ultimately, he began attending on his own. However, he confessed to being uncomfortable and feeling “very strange” within the congregation “seeing nothing but white people.” But he said, “Still I felt good being there, that there, given that there was a purpose for me being there.”[25]

Given this situation, Cleaver expressed a desire “to talk to some black” Latter-day Saints. Accordingly, local Church officials arranged for Cleaver to meet some black missionaries. One was Danny Frazier, a one-time linebacker for the BYU football team. Cleaver characterized Frazier as “as a shining jewel of a young man” who related to Cleaver how he became a missionary. Frazier explained how he had been so hung up on football that he didn’t think he would have become a missionary. However, “he broke his neck while playing for the university, which he proclaimed “a blessing in disguise” declaring himself “really happy to be on a mission.” Frazier went on to bear his testimony, which Cleaver claimed “relaxed me on the whole question of whether or not blacks belonged in the Mormon Church.” Cleaver also met with a second black missionary, Alan Cherry, who likewise “shared a very powerful testimony.”[26]

Cleaver’s commitment to the Church was further strengthened by his close association with Skousen. Cleaver’s initial speech for the Freeman Institute was in January 1981 to the Century Club on the campus of BYU, attended by an audience of more than nine hundred. Subsequently Cleaver, with Skousen’s enthusiastic backing, spoke at some twenty-five to thirty events throughout the western United States and into Canada.[27] Cleaver was reportedly paid some $500 for each lecture he delivered.[28]

Cleaver and Skousen became extremely close, despite their contrasting backgrounds and experiences. Skousen was a one-time Federal Bureau of Investigation agent and former Salt Lake City police chief prior to his founding the Freedom Institute. He had, moreover, vigorously defended Mormonism’s black priesthood ban prior to 1978, lambasting its critics of “distorting [this] religious tenet . . . regarding the Negro” labeling them “Communist dupes.”[29] Such differences notwithstanding, the pair shared extreme conservative and strident anticommunist beliefs. During visits to Utah, Skousen provided Cleaver lodging and other accommodations.

Linda Kimball, executive secretary of the Freeman Institute, actually scheduled Cleaver’s speaking engagements. In the process, the two developed a close relationship. Kimball characterized Cleaver “a brother” whom she “loved very much.” At the same time, she expressed concern about Eldridge and Kathleen’s turbulent marriage (the pair was still together at this point), noting that “they argued a lot,” adding that Kathleen clearly “had her own agenda.”[30]

Concurrently, Cleaver formed a close association with Sun Myung Moon and his Unification Church, lecturing at colleges and universities throughout the United States under the sponsorship of the College Association for the Research of Principles (CARP). Unification officials characterized Cleaver as an “associate and friend,” further noting that “a lot of our ideas are similar.” Cleaver agreed that his “association with them has been a positive one” but denied any intention of becoming a member. Rather he characterized himself a “spiritual guerilla in the army of Jesus.”[31] Whatever the case, Cleaver was reportedly paid $1,500 for each speech he delivered on behalf of CARP.[32]

Meanwhile, in early 1981, Cleaver made clear his intention to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which attracted media attention in Utah and throughout the nation.[33] Cleaver himself, when asked about his decision, told a newspaper reporter, “I am very enthusiastic about what I am learning . . . my spiritual journey in the past five years has led me to this point.”[34] To another reporter he remarked that becoming a Mormon would be the culmination of a long search “for someplace to fit in. . . . I just feel at home in the church.”[35] He further noted to a third media representative that he was drawn to the faith by “the warmth” that individual Latter-day Saints manifested toward others and appreciated “the church’s emphasis on close families.”[36] And to yet a fourth reporter, Cleaver claimed he had found his spiritual home declaring: “You find a different spirit in different groups, and the spirit among Latter-day Saints [is one] that I feel comfortable and at home with.”[37]

Finally, nearly three years later on December 11, 1983, Cleaver was formally baptized a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the Oakland Inter-Stake Center—the ordinance performed by his good friend, Carl Loeber. He was then confirmed by Dennis Peterson, likewise a close family friend and Cleaver’s former bishop. The service was “well-attended,” attracting “upwards of 100 people including many of Cleaver’s LDS friends from the San Jose area.” At the same time, Dean Criddle Bishop of the Oakland First Ward, to which Cleaver belonged following his move from San Jose to Oakland, acknowledged that the new convert had “a high profile in the sense of name recognition in this area.” He carefully added, “Only time will tell how well he is accepted in the Church, but I think the members of this ward will accept Eldridge just as they would any other convert baptism.” Later that same month, on December 25, Bishop Criddle ordained Cleaver a Priest in the Aaronic Priesthood.”[38] In January 1984, Cleaver addressed an assembled group of Latter-day Saint faithful at a Fireside in Walnut Creek, detailing his spiritual odyssey culminating in becoming a Latter-day Saint, forcefully concluding with a powerful personal testimony as to the truthfulness of the Gospel.[39]

However, Cleaver’s direct involvement in the Church soon waned and completely ended by the late 1980s, although he remained a member of record. According to Bishop Criddle, Cleaver “attended episodically” the Oakland First Ward and when present was more an “interested observer” rather than an “active participant.” Crittle attributed Cleaver’s frequent absences to his schedule as a speaker with the Freeman Institute and involvement in local politics.[40]

Cleaver’s activities continued to wane following his move from Oakland to Berkeley in 1985. Robert Gamblin, Berkeley ward bishop, recalls Cleaver’s “sporadic attendance,” adding that when present “[he] kept pretty much to himself,” further noting that he was not one to socialize with fellow ward members.[41] Cleaver’s involvement with the Berkeley ward had come to a complete halt by the time Steven Ferguson succeeded Gamblin as bishop. Cleaver’s inactivity caused concern at LDS Church headquarters, with Church officials directly inquiring as to Cleaver’s status.[42] In one last effort at reactivation, Cleaver was encouraged to attend the Oakland Ninth Branch—a predominately black congregation. As recalled by Branch President Edgar A. Whittingham, himself an African American, Cleaver attended only a couple of times, although he participated in a Black History Day observance sponsored by the branch.[43]

The obvious question is: what factors prompted Cleaver’s precipitous withdrawal from Church activity—most surprising given his extreme enthusiasm prior to actual baptism? Most important were the residual effects of Cleaver’s separation and ultimate divorce from Kathleen. Eldridge was left alone with her departure; she took their two young children. Particularly difficult was losing primary custody of his son and daughter. Eldridge had been a caring, committed parent. His son, Ahmad Maceo, fondly recalled: “My sister and I had a warm relationship [with him], even throughout his [difficult] struggles with our mother.”[44] Aggravating the situation was Kathleen’s steadfast refusal to become a Latter-day Saint, despite Eldridge’s repeated efforts to get her to join, right up to the time of their final divorce in 1986.[45]

Also contributing to Cleaver’s lapse into inactivity was his change of residence, moving from San Jose to Oakland, and, ultimately, to Berkeley. In the process, he left behind a close circle of Latter-day Saints with whom he had interacted during the three years prior to his baptism. The most important of these were Carl Loeber and Lee Senior, along with Dennis and Sonja Peterson, all of with whom he developed close friendships. By contrast, he was unable and/or unwilling to cultivate a similar level of interaction with any of his coreligionists in the Oakland and/or Berkely wards. Further aggravating his estrangement, he stood out as a single, divorced African American in both wards, given that the vast majority of the members were white, with a significant portion married and with families. By contrast, a mere handful of African Americans attended the two wards.

With acute perception, Sonja Peterson noted that Cleaver “would have been much better off if he could have gotten out of the Bay Area.”[46] Likewise, W. Cleon Skousen failed to convince Cleaver to move from the Bay Area to Salt Lake City, thus placing him closer to both the Church and the activities of the Freeman Institute. Worse still, Skousen was ultimately forced to dismiss Cleaver as a Freeman Institute speaker, given his continuing failure to show up at events at which he was scheduled to speak. Skousen later lamented, Cleaver “lost his grip” in the wake of his divorce, “collapsing” both mentally and psychologically.[47]

A third factor drawing Cleaver away from the Church was his active involvement in local and state politics. In early 1984, Cleaver announced his candidacy for a seat in the US House of Representatives as an Independent, in opposition to incumbent Democrat Ronald Dellums, among the most liberal members of Congress who represented the region encompassing Oakland and Berkeley. In emphasizing his own qualification as a staunch conservative and fiery anticommunist, Cleaver lambasted Dellums as “a pliable tool in the hands of the Marxist-Leninist puppet masters . . . [and] a third world worshipper.”[48] But the lively contest between the two African Americans ended in August 1984 with Cleaver’s withdrawal, as he instead opted to run for a seat on the Berkeley City Council. Again, Cleaver campaigned as an arch conservative lambasting the City’s rent control laws and its antibusiness atmosphere, positions that did not go down well, given Berkeley’s reputation as a bastion of left-wing radicalism. Not surprisingly, Cleaver finished dead last in a field of fourteen candidates.[49]

Undaunted, Cleaver made one last bid for political office. In 1986, he sought the Republican nomination for a US Senate seat. In what was a high-profile contest, Cleaver managed to temporarily capture the limelight with his witty one-liners, characterizing himself as “a leader with a proven track record [and] Ronald Reagan Black Panther.”[50] In the actual contest, Cleaver fell far short, finishing eighth in a crowded field of twelve candidates.

In all three contests, Cleaver deliberately avoided any reference to his LDS Church membership. Moreover, following his abortive quest for a seat in the House of Representatives, he accused his two campaign managers, both Latter-day Saints, of stealing some $350,000 in campaign contributions, further lamenting that neither the government nor the LDS Church disciplined the men for their actions. This, in turn, further facilitated his estrangement from the Church.[51]

In the wake of his failure in the political arena, Cleaver became more erratic and unpredictable in his behavior and actions, which, in turn, pushed him even further away from the Church. Such behavior resulted in large part from the fact that he continued to struggle financially. He sought publication of a series of essays and poems that he continued to write during this period, albeit unsuccessfully. He also made and sold handcrafted flower pots and sculptures and collected and sold recycled cans and bottles that he had gathered off the streets—all such endeavors producing limited revenue.[52]

In desperation, Cleaver promoted a bizarre money-making scheme, dubbed “The Treasure Island Liberation Front.” He hoped to take over Treasure Island—a US Navy Instillation in the San Franciso Bay between Oakland and San Fransisco, where he claimed a treasure chest of jewels had been secretly buried years earlier. He claimed that he possessed a map revealing the treasure’s location and proceeded to lobby the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to demilitarize Treasure Island to facilitate a search for the treasure. Calling himself “Captain Cleaver,” he offered to disclose the location of the treasure on condition that he be allowed to keep it. Not surprisingly, local officials ignored his unusual request.[53]

Cleaver was no stranger to bizarre money-making schemes. A decade earlier, he had designed a uniquely styled men’s pants. Dubbed the “Cleavers,” his pants contained an exterior codpiece that highlighted the male genitals. Critics were quick to condemn his unusual pants as “frivolous and risqué.” Undaunted, Cleaver defended his jeans as “a statement against the unisexual ideology that has been structured into our clothing and being pushed by organized homosexuals.”[54] He further asserted that the Cleavers were “destined to revolutionize men’s fashion and corner [the] world market” while freeing men from what he called “the fig leaf mentality.” His pants, he asserted,” would eventually make blue jeans look like ‘girl’ pants.” Despite his efforts at promotion, including a sexually explicit ad in Rolling Stone magazine, the Cleavers proved a flop.[55]

In response to his continuing series of disappointments, personal, political, and financial, Cleaver sought solace in drugs, specifically crack cocaine, which was “flooding Oakland and other inner-city neighborhoods across the United States in the mid-1980s.”[56] Cleaver’s addiction precipitated yet a further decline in his fortunes. In October 1987 and again in June 1992, he was arrested on charges involving possession of crack cocaine. Most serious, in March 1994, Cleaver was attacked and nearly killed in a crack deal gone bad. He was robbed and hit hard on the head with a blunt instrument. Found by police dazed and wandering the streets of Oakland, he was initially arrested. But upon discovering the extent of his injuries, authorities rushed Cleaver to a local hospital where he underwent five hours of emergency surgery for bleeding between the brain and skull. Following that, he went through a lengthy period of recuperation.[57]

Meanwhile, Cleaver found companionship during this painful period with Karen Koelker, whom he met through a mutual acquaintance. The two enjoyed an intimate relationship, with Karen becoming pregnant. But upon discovering that their child-to-be showed signs of serious birth defects, the medical professionals with whom they consulted “urged her to have an abortion.” But the couple rejected this option. “We wanted the child, and when our son was born, [in 1986] I didn’t see anything bad about him. I just saw him as little.” They named their son Riley, and despite being born with Down syndrome, Eldridge “loved him fiercely.” Though the couple never married, “they shared an intimate relationship through their coparenting of Riley,” who provided Eldridge “a much-needed source of affection throughout the rest of his life.”[58]

Cleaver’s withdrawal from active involvement in the LDS Church notwithstanding, he was vacillating concerning his own beliefs and about Mormonism in general. As Carl Loeber, his close friend and fellow Latter-day Saint sagaciously noted, “Cleaver’s commitment to the Church was ambivalent and nontraditional in that he wanted to be a Mormon but did not want to make the commitment to go to Church on a regular basis.”[59] In a 1988 interview with Ebony magazine, Cleaver characterized himself as a “devout Mormon,” further stating that the Church had “an adherence to the gospel [and] a very positive program for human beings, for families and so forth” but carefully adding “the fact that Black people were not traditionally [Mormons] was obvious to me.”[60] Some seven years later, he confessed to a Salt Lake Tribune reporter that while he was “no longer active in the Church, anymore” he remained a “supporter,” further stating, “I am powerfully impressed with the message of the Church and the social practice of the Church. They do a very good job of taking care of their people [but] I wish they would allow women to have a more equitable role.”[61]

However, Cleaver made no reference to his involvement in the Church in a series of subsequent media interviews. Responding to a question about the role of spirituality in his own life, he assigned it a “central role” given that “fundamentally our challenge is to respect and love one another” and to “get rid of all of our pet hates, particularly racism and misogyny.”[62] Similarly, in a July 1995 interview conducted by Mike Castro of the California-based McClatchy News Service, Cleaver made no mention of his Mormon affiliation, simply characterizing his “current religious views [as] attuned more to nature and less to an established institution.”[63] A year later, in April 1996, People Weekly quoted Cleaver, stating, ”Christianity is my reality now,” in describing his then-current association with the Daniel Iverson Center for Christian Studies in Miami, Florida.[64]

Finally, at the memorial service held at the Wesley United Methodist Church following Cleaver’s death on May 1, 1998, no mention was made of Cleaver’s Mormonism. Although he had been nicknamed “the rage” during his Black Panther days, he was eulogized as “a gentle spirit.” His tombstone at the Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena, California, was inscribed with the epitaph: “A loving Heart, An Open Hand.”[65]

In conclusion, the obvious question is: what is to be made of Eldridge Cleaver’s encounter with Mormonism? Some have questioned the sincerity of Cleaver’s conversion. John George, a longtime acquaintance and former fellow Black Panther, labeled Cleaver “a con artist [who] could have conned himself so that he believes. . . . Isn’t that a kind of religiosity?”[66] Assessing Cleaver’s conversion from a vastly different perspective, writer James Craig Holte suggested that Cleaver’s most outstanding trait was “continual change,” characterizing him as an individual who seized “the opportunity to make himself over more than once,” carefully adding that he was not unique in this regard: “Most people undergo a series of transformation events in their lives that can be called conversions.”[67]

Eldridge Cleaver’s passage through Mormonism provides an intriguing case study into the complex nature of religious conversion. Mormon historian Thomas Alexander has suggested that Cleaver’s involvement with the Church represents a forlorn “search for community” that eluded him throughout his turbulent life.[68] Whereas sociologists Richard J. Jensen and John C. Hammerback assert that Cleaver’s “dizzying shifts in associations, actions, and words” were not unique but experienced by many converts.[69] His embrace of Mormonism, following his involvement with “born again, mainline Christianity” represents what biographer Kathleen Rout has characterized as Cleaver’s return “to the fringe, where he had always felt more comfortable.”[70] Although, Jensen and Hammerback further argue that Cleaver was “essentially a spiritual and rhetorical being who remained faithful to his primary concern [of seeking] to create his self-portrait as a spiritual individual evolving through a series of religious experiences.”[71] By contrast, religious writer Randy Frame asserts that Cleaver “never matured spiritually because he rejected opportunities to be grounded in the faith,” having “little interest in introspection,” and therefore was “unlikely to be overscrupulous about the sincerity of his feeling for Jesus.”[72] Whatever the motives for joining the Church of Jesus Latter-day Saints, the story of Eldridge Cleaver’s encounter with Mormonism contains elements of irony, pathos, and, alas, unfulfilled potential.

Author’s Note The author wishes to thank the following for their assistance: Justin Gifford, professor of history at University of Nevada, Reno, for providing a copy of Eldridge Cleaver’s unpublished autobiography and for reading and critiquing an earlier draft of this article. Also reading and critiquing a preliminary draft were Matt Harris, professor of history at Colorado State University, Pueblo; Craig L. Foster, an independent scholar; and Greg Seastrom, professor emeritus, College of the Sequoias.

[1] Among the numerous secondary works chronicling the life of Eldridge Cleaver are three important book-length studies: Kathleen Rout, Eldridge Cleaver (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991); Kathleen Cleaver, ed., Target Zero: Eldridge Cleaver a Life in Writing (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006); and Justin Gifford, Revolution or Death: The Life of Eldridge Cleaver (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2020). Cleaver himself recalled the events of his life in two very different memoirs: Soul on Ice (New York: McGraw Hill, 1968) and Soul on Fire (Waco, Tex.: Word Books, 1978). Three other book-length studies are worthy of note. They are Robert Scheer, ed., Eldridge Cleaver: Post-Prison Writings and Speeches (New York: Random House, 1969), which provides further insights on Cleaver’s radical activism during the late 1960s. Whereas George Otis, Eldridge Cleaver: Ice and Fire (Van Nuys, Calif.: Bible Voices, 1977), and John A. Oliver, Eldridge Cleaver Reborn (Plainfield, N.J.: Logas International, 1977), both focus on Cleaver’s emergence as a “born-again Christian” following his return to the United States in the wake of his exile abroad.

[2] Three accounts dealing with Cleaver’s involvement with Mormonism include: Richard J. Jensen and John C. Hammerback, “From Muslim to Mormon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Rhetorical Crusade, Communications Quarterly 34, no. 1 (Winter 1986): 24–40; Newell G. Bringhurst, “Eldridge Cleaver’s Passage Through Mormonism,” Journal of Mormon History, 28, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 81–110; and Jesse Walker, “Eldridge Cleaver: The Mormon Years,” Friday A/V Club, posted online May 7, 2021. Also see Newell G. Bringhurst and Craig L. Foster, The Mormon Quest for the Presidency (Independence, Mo.: John Whitmer Books, 2008), 162–183, which focuses on Cleaver’s 1968 campaign for president as the nominee of the insurgent Peace and Freedom Party.

[3] Rout, Eldridge Cleaver, 260. Underscoring the author’s superficial knowledge of Cleaver’s involvement with the Church, and indeed Mormonism in general, Rout mistakenly dates his conversion to “sometime in 1982” while characterizing Mormonism as “a religion that does not permit blacks to hold significant offices in the hierarchy” further stating that “among major American religion [Mormonism] is the only one with an overtly anti-black creed,” (259–260).

[4] Gifford, Revolution or Death, 263–264. Gifford, moreover, misrepresents Cleaver’s response to Mormonism’s recently lifted black priesthood ban, mistakenly asserting that Cleaver dismissed its significance “by pointing out that the Mormons, unlike Christians had never owned any slaves” (263).

[5] Cleaver, Target Zero. Although in a foreword penned for the volume, Henry Louis Gates Jr. makes passing reference to Cleaver’s involvement with the Church: “We were even more shocked when [Eldridge] announced his conversion, a la Charles Colson, to a born-again variety of Christianity, including eventually a sojourn with the Mormons” (viii).

[6] In fact, significant portions of the previously unpublished The Autobiography of Eldridge Cleaver, as labeled, have been included in Kathleen Cleaver’s edited Target Zero, specifically, chapters 1 and 2, 9–14; chapter 4, 195–198; chapter 7, 265–270; and chapter 9, 275–278. Omitted from Target Zero is the section discussing Cleaver’s involvement with the Church. A typescript copy of this latter section was provided to this author courtesy of Justin Gifford as part of a fifty-five-page unpublished manuscript he obtained directly from Kathleen Cleaver in the process of researching his Death or Revolution. According to Gifford, the manuscript was subsequently deposited in the Kathleen Cleaver Papers at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. However, efforts to locate the manuscript in that collection have been unsuccessful.

[7] Rout, Eldridge Cleaver, 152–157. Christlam had an unusual “social auxiliary” called “Guardians of the Sperm,” “formed in response to Cleaver’s assertion that ‘the dwelling place of God’ was not in the North African desert in Meca, as in traditional Muslim belief, but ‘in the male Sperm’ Cleaver saw his church’s mission clearly as a sex facilitator,” as further noted by Rout.

[8] Walker, “Eldridge Cleaver.” Although as Walker further notes, “it wasn’t completely clear how he felt about Moon’s religion.”

[9] Al Martinez, “Eldridge Cleaver: Time Tempers the Passions, Dreams,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 1, 1981, 1–3.

[10] Eldridge Cleaver, “Unfinished Autobiography” (unpublished manuscript). Original in Kathleen Cleaver Papers, Emory University, Special Collections Library, Atlanta, Georgia.

[11] Cleaver, “Unfinished Autobiography.”

[12] Cleaver, “Unfinished Autobiography,” 49–50.

[13] For a discussion of Cleaver’s 1968 presidential campaign, see Newell G. Bringhurst and Craig L. Foster, “Eldridge Cleaver,” in The Mormon Quest for the Presidency, 162–183.

[14] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography,” 50.

[15] Sonja Benson Peterson, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 28, 2022.

[16] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography,” 53.

[17] W. Cleon Skousen, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, June 4, 1996.

[18] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography,” 52.

[19] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography,” 52–53.

[20] Sonia Peterson, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 28, 2022.

[21] As vividly described and thoroughly documented by Gifford, Revolution or Death. See in particular 145, 149, 192–193, 197–199, 266–267, 289.

[22] Kathleen Cleaver, “Introduction,” in Target Zero, xxii, xxiv.

[23] Robert Gamblin, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, June 3, 1996.

[24] Lee Senior, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 26, 2022.

[25] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography.”

[26] Cleaver, “Unpublished Autobiography,” 52.

[27] W. Cleon Skousen, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, June 4, 1996.

[28] According to Carl Loeber, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 20, 2022.

[29] W. Cleon Skousen, “The Communist Attack on the Mormons,” 1970.

[30] Linda Kimball, telephone interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 27, 2022.

[31] Martinez, “Eldridge Cleaver,” I-3.

[32] According to Lee Senior, telephone conversation by Newell G. Bringhurst, Apr. 26 2022.

[33] Peter Gillins, “Ex-Radical Mulling Mormonism,” Salt Lake Tribune, Jan. 23, 1981, B-2; Larry Werner, “Cleaver Studies LDS Teachings,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 11, 1981, D-1; “Cleaver Vows to Join LDS,” Salt Lake Tribune, Apr. 6, 1981, B-1; “Cleaver Sets Baptism after Parole,” Salt Lake Tribune, Oct. 11, 1981; “Cleaver to Join LDS Church,” Deseret News, Apr. 3, 1981; “Cleaver Says He Will Join Church,” Deseret News, Apr. 6, 1981; “Mormons Say Eldridge Cleaver’s Planning to Convert,” New York Times, Jan. 24, 1981, 46; “Eldridge Cleaver Converted,” Indianapolis Star, Apr. 7 1981; “Eldridge Cleaver May Join Mormon Church,“ Jet, Feb. 19, 1981; Lynne Baranski and Richard Lemon, “Black Panthers No More, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver Now Lionize the US System,” People Weekly, March 22, 1982.

[34] George Raine, “Cleaver Promotes God, Patriotism,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 12, 1981, B-1.

[35] “Cleaver Says He Will Join Church,” Deseret News, Apr. 6, 1981.

[36] Martinez, “Eldridge Cleaver”; “Cleaver Sees Baptism after Parole,” Salt Lake Tribune, Oct. 11, 1981, B-1.

[37] “Cleaver to Join LDS Church.”

[38] “Eldridge Cleaver Baptized!,” The Sunstone Review, Feb. 1984, 6.

[39] Eldridge Cleaver, remarks delivered at Fireside in Walnut Creek, Jan. 8, 1984.

[40] Dean Criddle, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst, June 2, 1996.

[41] Robert Gamblin, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst, June 3, 1996.

[42] Steven Ferguson, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst, June 2, 1996.

[43] Edgar A. Whittingham, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhust, May 31, 1996.

[44] Ahmad Maceo Cleaver, as quoted in Gifford, Revolution or Death, 256.

[45] Robert Gamblin, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst, June 3, 1996.

[46] Sonja Peterson, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst.

[47] W. Cleon Skousen, telephone conversation with Newell G. Bringhurst, June 4, 1996.

[48] Katherine Ellison, “Eldridge Cleaver Squares Off Against ‘Cesspool’ of the Left,” San Jose Mercury-News, March 3, 1984, A-7.

[49] “Eldridge Cleaver Runs for Berkeley City Council,” Fresno Bee, Aug. 13, 1984, A-2; Barry M. Horstman and Maura Dolan, “Indicted Mayor Victor in San Diego Balloting,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 7, 1984.

[50] Jeff Rainmudo, “Mud-Slinging GOP Convention,” Fresno Bee, Mar. 9, 1986, A-#; Jim Boren, “Candidates Seeking Support Platform for Republican Delegates, Fresno Bee, Apr. 1, 1986, A-1.

[51] Jennifer Skordas, “Cleaver Did It: From Panthers to Mormonism,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 15, 1995.

[52] Gifford, Revolution or Death, 276–280.

[53] “Cleaver Says Treasure Buried at Navy Base,” Visalia Times-Delta, Sept. 25, 1987. A-3; “Eldridge Cleaver Leads Fight to ‘Liberate’ Treasure Island,” Oakland Tribune, Sept. 25, 1987.

[54] Randy Frame, “Whatever Happened to Eldridge Cleaver?,” Christianity Today, Apr. 20, 1984, 38.

[55] As quoted in Gifford, Revolution or Death, 238–240. The provocative Rolling Stone ad stated: “Walking Softly But Carrying it Big . . . You’ll be Cock of the Walk with the New Fall Collection from Eldridge de Paris” (240).

[56] Gifford, Revolution or Death, 276–281.

[57] Bringhurst, “Eldridge Cleaver’s Passage Through Mormonism,” 101–102.

[58] Gifford, Revolution or Death, 274–275.

[59] Carl Loeber, interview by Newell G. Bringhurst, Aug. 8, 1996.

[60] “Whatever Happened to . . . Eldridge Cleaver?” Ebony, May 30, 1996.

[61] Skordas, “Cleaver Did It,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 15, 1995.

[62] Michael Peter Langevin, “Eldridge Cleaver: You Say You Want a Revolution,” Magical Blend Magazine, no. 48, online edition.

[63] Mike Castro, “Soul Searcher,” Fresno Bee, July 27, 1995.

[64] “Free at Last,” People Weekly, April 15, 1996, 80.

[65] Patrick J. McDonnell, “Ex-Panther Is Mourned,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1998, B-1, B-2; “Former Black Panther Leader Cleaver Dies,” Visalia Times-Delta, May 2, 1998, A-1, B-2.

[66] Quoted in Martinez, “Eldridge Cleaver,” I-3.

[67] James Craig Holte, The Conversion Experience in America: A Sourcebook on Religious Conversion Autobiography (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1992), 29.

[68] As suggested by Thomas G. Alexander; comments on paper by Newell G. Bringhurst presented at 1996 meeting of the Western Historical Society, 1996. Photocopy in my possession.

[69] Jensen and Hammerback, “From Muslim to Mormon,” 24.

[70] Rout, Eldridge Cleaver, 255.

[71] Jensen and Hammerback, “From Muslim to Mormon,” 24, 33–34, 38.

[72] Frame, “Whatever Happened to Eldridge Cleaver?,” 39.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue