Articles/Essays – Volume 58, No. 1

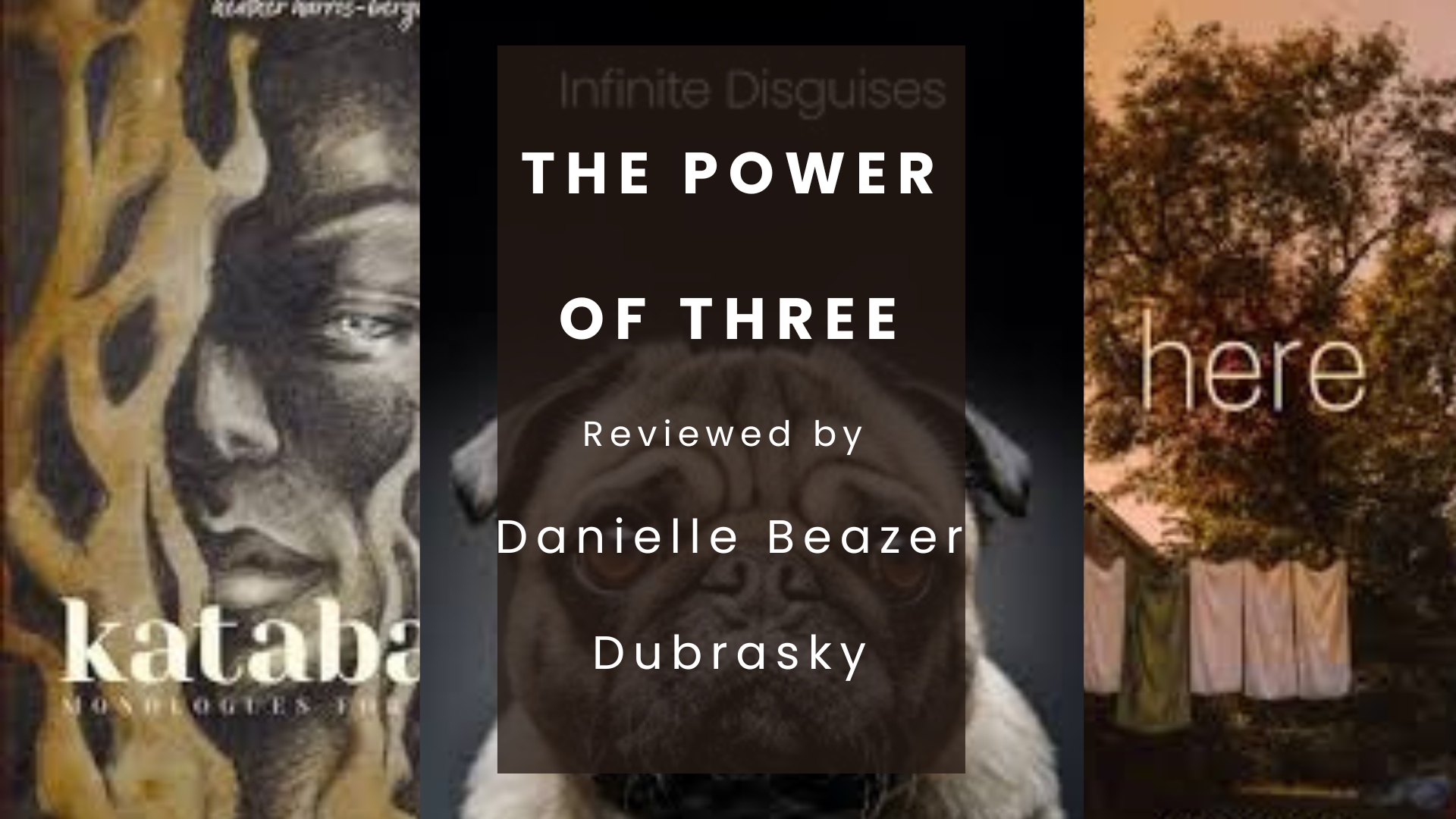

The Power of Three: A Trio of Poetsand Mormon Feminist Poetics | Heather Harris-Bergevin, Katabasis; Susan Elizabeth Howe, Infinite Disguises; and Darlene Young, Here

In her introduction to her book Katabasis, Heather Harris-Bergevin quotes someone who accused her at one time of “consorting with witches.” The word “witch” comes from an Old English “wicce,” meaning “female magician or sorceress.” In delving further, one finds the phrase “a woman who practices incantations.” The word “incantations” is further broken down and becomes “to sing spells.” The notion of the witch, closely related to the word “magi,” has been recast over the years in a feminist revision. It seems fitting to apply the notion of “magi” to three poets whose works contain various “singing spells” of poetry. These collections each exemplify a kind of feminist Mormon poetics, presented in varying degrees: slyly subtle in Susan Elizabeth Howe’s Infinite Disguises, more apparent in Darlene Young’s Here, and defiantly present in Heather Harris-Bergevin’s Katabasis.

In one poem by Susan Elizabeth Howe, there is the line, “Don’t I have any words at the center of my life?” This line not only expresses the question every poet asks themselves, but it is also an oblique apostrophe to Emily Dickinson, a primary motif throughout Infinite Disguises. Reference to Dickinson’s poems reverberate throughout the sections—a poem that explores the idea of “telling it slant,” another one on a “way of seeing” by looking into the dye of crushed cochineal beetles, or by giving a nod to a buzzing fly, and finally through a full address to the poet in “Oh, Emily.” The idea of conjuring a connection to Dickinson’s poems is prevalent, but so is the desire to find the source, the matrix—not only the artistic medium. Not the poems, but Emily Dickinson herself. This desire is implied through various images and references to origins. The speaker seeks not the artwork inscribed on sandstone but the touch of the Indigenous woman who left her handprint behind, in the poem “All Things.” Not Perry Mason but the writer who created him in “The Case of the Jilted Jockey.”

What is also impressive in this collection is the range of tone and focus. Some poems lean toward humor, wordplay, or satire, as does the clever poem “The Tenants of Philosophy,” which takes its inspiration from a student’s malapropism of the word “tenets.” In this poetic sleight of hand, Howe riffs on the idea of the “tenants of Emerson’s philosophies,” imagining “nihilist tenants,” “idealist tenants,” and so forth. Other poems pointedly comment on aspects of social justice. “Meth Child” poignantly addresses the trauma experienced by the “Little wanderer who came to earth / in a sand-filled tire of the park / where your mother gave birth.” Another poem, “The Last Villager,” speaks in the persona of the witness to the violence that has taken everything. Other poems address what it means to be living in the United States now, often “battered by television news,” living in a time that has “let zombies into art as well as dinner conversations.” Howe’s poems are incantations: through the power of her words, they create a linguistically sharp vision that not only sees the exterior details, the “tiny female beetle that / . . . lives on the toughness / around the prickly pear’s spikes,” but also interior perspectives as these lines describe the mind of a poet (Dickinson) who “must often have wandered / the desert of bitter and little.” This contrast is seen powerfully in another song-spell—“no map detailed as a dragonfly’s eye, / no eye like earth as far galaxy.”

Darlene Young’s Here follows a different motif—that of a mother following the development of her son from youth to young adulthood through priesthood rites. In these poems, Eve is the feminist icon: a woman formed in a patriarchal world who is rhetorically placed at its center—the mother of all living, revered for her body’s procreative powers—but in reality, she exists on the periphery with minimal power. As Young’s poems express this paradoxical stance, the collection becomes a kind of tapestry in which the experience of having a female body—as wife, as mother, as aging woman—is woven into a search for God, her creator, who placed her in a world of paradoxes. The poems set Eve as a foil against a contemporary Mormon mother’s journey of raising her son. The poem “Lone and Dreary: Cain Comes Home from the Field” contains a line that expresses the theme of the book: “The tumble of boys— / and then the horizon. / They grew. Natural, to want / to see for themselves. / Horizon: a mother’s fear.” This idea of knowing that the future will inevitably separate the son from his mother explains the book’s title, Here, which calls us to pay attention—there is only the present, and all things move forward through time. Pay attention to the song of birds in the morning, to a couple’s argument, to what is not said in a letter from the son written while he is on a mission. A kind of urgency compels these poems, an awareness that mortal life is temporary.

A prominent tapestry thread throughout the poems is the way the son inhabits his own space in this patriarchal world that the mother knows she can never truly be a part of: His coming of age and attempts to attract girls, his early morning service projects, the Young Men’s weeklong rafting trip over which she has no control, and finally the mission itself. Behind the image of Eve as the prototype for “mother” is the deceased mother of the speaker. The occasional memory of her presence informs the speaker’s anxiety of losing her thread to the next generation; it is implied that the thread to her own mother was cut short. Other poems address what it means to have a female body—to experience the “hot flash, the strangle of clammy clothes,” the anxiety of having a breast biopsy, or to imagine Eve’s womb wrenching “at the sight of that blood / her own seed” on Cain’s return without his brother. Young creates some resolution for the emotional journey that accepts the aging body in the poem “Hot Flash.” The body that conceived, gave birth, and said goodbye to the son is embraced through an image that finally gives it autonomy and that conjures up a dance similar to that of imagined witches: “Shut up. I’m not done dancing / The best belly-dancers are older women, pant- / omiming birthing, earth / goddesses, crones.”

The final collection, Katabasis by Heather Harris-Bergevin, draws on many feminist motifs through Greek myths, Judeo-Christian myths, fairy tales, as well as Mormon history and lore. This collection starts as a conventional epic: “I will raise you up brim-filled with stories.” The first poem invites the reader into a journey that explores many facets of being female, queer, or any kind of “Other” in a world defined by patriarchy. Those facets are also shaped by the inherent wounds one experiences as an “Other” within a patriarchal system. There is even a female guide—the sea nymph Thetis—who takes the place of Virgil; however, she presents herself as an unreliable guide as she refers to potential destruction by two monsters who were once women but have been punished (wounded) by the Greek gods for their transgressions. The wounds are various—psychological, physical, sexual—as the poems move through one unsettled voice to another. Poems written in personas of literary women, nymphs, or goddesses from Greek myths are foils to a contemporary voice that pushes against patriarchal convention that is often Mormon and toxically masculine. In some poems, the story of the hurt is clear—in others, more opaque. But each poem offers a surprising turn as one is not sure which story will be encountered next.

The ways in which myths and fairy tales have constructed gender in society is deconstructed as the reader follows a journey that seems to also search for the divine source that would allow for such a punitive gendered chaos. Whether the source be through a female psyche that is the universe, or through a masculine father/God, or through a nonbinary sense of the divine, there is a slippage between philosophies, myths, divinities, and more personal poems that creates a labyrinthine journey. Cleverly placed at the labyrinth’s center is the poem “Chicago,” about the artist Judy Chicago and the famous vaginal dinner plates, which lists a pantheon of goddesses and feminist writers as inspiration. From this point in the book, the labyrinth turns away from Greek influence toward poems in the persona of biblical women, Mormon polygamous women, or other women connected to Christianity. These poems express the paradox of being a woman asked to worship a God whose patriarchal laws create bondage over women’s bodies rather than agency. Katabasis explores a complex feminist intertextual theology that pushes back against most Judeo-Christian norms while ultimately centering on what is finally deemed to be truly sacred—the mother/child dyad. In that sense, these poems turn the father/child dyad, so prevalent in Mormonism, on its head. Mary’s relationship with Christ, as his mother, supersedes all other divine powers. Similar to Darlene Young, Harris-Bergevin addresses the paradox of a religious culture that espouses the significance of experiencing life in a female body and extols the power of motherhood yet neurotically erases any notion of a female deity or matrix.

To read these three books together is to be invited into a trio of Mormon feminist poetics that explores how poetry can transcend time and delve into spaces of origin, how it can restore the severed dyad of mother and child, and how it can insistently defy ancient stories that define contemporary attitudes about gender. The three poets’ voices—three magi—are vastly distinct, but they share a question that would be recognized by women familiar with a Mormon upbringing. Behind the many female icons—Emily Dickinson, Eve, Greek goddesses and Judeo-Christian literary women—the poems ask: Where is the matrix, the Mother, and how can she be made more visible? Thus, the unasked question in these poems is Where did we come from? Where is the divine body through which women can hear the words: “Let us make woman in our own image, after our likeness”?

Heather Harris-Bergevin. Katabasis: Monologues for the Dead. BCC Press, 2023. 268 pp. Paper: $9.99. ISBN: 978-1948218894.

Susan Elizabeth Howe. Infinite Disguises. BCC Press, 2023. 79 pp. Paper: $9.99. ISBN: 978-1-948218-90-0.

Darlene Young. Here. BCC Press, 2023. 91 pp. Paper: $9.99. ISBN: 978-1-948218-88-7.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue