Articles/Essays – Volume 13, No. 2

A Ford Mustang

High school boys with big dreams, I was one of them; I longed for freedom, for a Ford Mustang with meats and headers and dual glass-packs. And then too, I suppose I was tired. John and me would stand around the halls leaning against the lockers in stoic boredom, with our arms folded over our chests, watching the others scurry by us.

John quit school about three weeks before I did. He was an epileptic, and he had to lie about it to get the job driving trucks with Millers Blue Ribbon. But while John was in school, the epilepsy came in handy. He and I both had Maury Friffin, the gangly old coot with hornrims and a lisp, for geography, and when things got too thick, John would stage a fit, and the old coot would prance around tangling and untangling his fingers and sputtering, “Oh my, oh my.”

John was different somehow from the others. I suppose it was that epilepsy. He got sick, and nothing interested him any more except that broken down Honda 350 he drove everywhere. At the beginning of our junior year, old John was really sick, and some of the treatments they gave him made his hair fall out. I’ll never forget that day in the fall when I drove my mother’s 69 Dodge Dart and John pulled up alongside on his bike wanting to race. I hit the gas, and when I turned to look at John, I saw that the wind had caught the front of his hair piece and was peeling it back, and finally it was flapping in the wind behind his bald head that was smeared with this black goop. What a killer.

But, in the spring, John quit school and got the job driving truck for Millers Blue Ribbon, and first thing I knew, John owned a brand new Honda 750 with extended forks and a leather double-decker seat. John started hanging around school again, moping around after school let out, letting on how rich and famous and romantic trucking was—and I believed him. John dreamed about trucks and motocydes; I dreamed about a Mustang, a Ford Mustang. I had dreams about driving that car—not just any car, a souped-up Mustang—and I’d be sitting there at Pete’s Tastee Freez when some young thing’d come out with a mug of root beer. I’d drink the root beer; she’d ask questions like these:

“Must take quite a man to handle all this power, huh?”

And I’d say “I suppose so.” (Then I’d tighten my chest and puff up in my dream.)

“You got to be pretty skilled to run something like this, don’t you?”

“Yep.”

Then she’d walk away from the car and watch for a long time as I drove it down Main.

Anyway, with John gone, it got lonely in the hall, leaning there by myself, trying to look stoic—so I quit school too and ended up there at Valley Discount, a grocery store, talking to Cleve about the opening in the butcher shop.

Cleve looked sedentary in his swivel chair. He sat behind an old army desk, a green desk, in an office that they built directly on top of the produce cooler, and right there by his desk was a peep hole that he’d scoot over to periodically and look out of. The hole was about as big around as your thumb, and I was later to learn that Clever (We called him Clever—Clever the Beaver—on accounts of his duck-tail haircut and the way he walked in his too-big shoes.) had peep holes all over the store. There was one of those holes right above the check stand, and it was no secret when Clever got up there to look at what was going on. Thelma the check-girl told me later on that Clever made so much noise up there looking through that peep hole that some of the customers would look up at him and see his eyeball in the hole.

Like I said, he looked sedentary in that swivel chair. When I stepped into the office, the compressors were going, and Clever couldn’t hear me, and he had his nose pressed against the peep hole trying to see if anything shady was going on in the coffee and pickle aisle. I snorted to make my presence known, and he jumped. After I gave him my application, he put on his glasses—he rested them way down on the end of his nose so he had to cock his head to read—and he leaned back in the chair. One of his feet flew up and kicked the metal army desk when he thought he was going over backward, and he snuffed and looked up at me.

“We need a butcher’s aid all right, but we need someone who’s going to be with us for a while. I mean, we do some valuable training, and we don’t want to waste it on somebody’ll be here just a short while. You plan on being around for a while?”

“Yes sir.”

“Well, you look like a good kid. Starting’s two dollars an hour, but you can work up fast, especially if you don’t horse play. I have a hunch that most of the workers here steal me blind. You promise me to be honest?”

“Yes sir.”

“Well, then, be here on Monday at eight o’clock and we’ll show you the butcher business.” As I walked out, I thought of the Ford Mustang I’d buy now I was working—it would be one hot car! And I saw the old boy in the meat department, humming something to himself as he worked on a piece of meat by the chopping block.

Monday morning when I came he stood by the porcelain sink scrubbing long aluminum trays. I hadn’t the foggiest what to do, so I just stood there with my back to him, and he didn’t say a word; he just hummed and cackled now and then.

I jumped the first time he clapped the aluminum meat trays together— they were loud, like a gun-shot, and all the old boy did was cackle.

“Oh-ho, fooled you, didn’t I?”

He started singing that song about the three dogs that died when he was born and scurried off into the walk-in fridge to grind some meat. “Oh-ho, three dogs died. . . . Oh-ho.”

After a minute he came out of the fridge and I noticed the meat scraps on the tops of his black wing-tips and the blood that stained his white apron. “What? Just standing?” He turned abruptly and walked back into the fridge. Again he appeared carrying a pile of meat and bone, and he threw it on the block.

“You bone that?”

“What’s that you say?” I asked.

“You mean you can’t bone! What kind of help they sending me? You ever worked in a shop?”

“What?” I asked again.

“You mean you haven’t worked in a shop! Oh hell.”

The old boy pulled out a steel and a slender boning knife and started running the blade up and down the steel with precision. “Yep, I been behind the counter fifty years. Started when I was sixteen. Lost three boys while doing it; they’re up on the hill now.”

His index finger shot out from the rest of his hand at an abrupt angle and he said he ran it through the slicer once. “Hell no—the lady just got an extra good bargain on her lunch meat, that’s all. Hell no, it never hurt me a bit. Here now, this is how you got to bone.”

He made a few quick slices at the meat and walked into the fridge. The grinder started. “Oh dee doe doe doe. Three dogs died, when I was born. Oh dee doe doe doe.”

During the morning he scurried from one end of the shop to the other, and the meat scraps collected on the tops of his wing-tips. At nine a woman came to the counter. I didn’t know what to do, so the old boy took her, and he said, “How doin’? Any better?”

The woman looked confused. “Better than what?”

“Oh hell, better than yesterday.”

“Why yes. I mean, fine, and you?”

“Oh I’m better than yesterday, but I’ll be on the hill tomorrow. What’ll you have.”

“Hamburger—a pound.”

“Oh dee doe doe doe,” he cackled to himself as he scooped the ground meat into the wax paper. I watched him from the block, his finger that stood out from the rest, different than the others, the meat on his wing-tips.

“Here’s the burger. See you tomorrow.”

Again the woman looked confused. “But I don’t . . . Er, I’m not coming. . . .” She hesitated for a second. “All right, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“The hell you will. I’m going to be on the hill with my dead boys tomorrow.”

The woman shook her head; she looked confused.

“Oh-ho.” The old boy went back into the fridge, and I kept boning the meat.

Pretty quick I heard the band saw start up in the walk-in fridge, and then I heard the sound of a bone going through the blade, and then the old boy screamed and gargled as if he’d lopped off an arm or something.

I ran to the door of the fridge and yanked it open, and there he stood with a beef shank in his hand.

I must have looked stupid.

“Oh-ho, fooled you didn’t I.” The old boy turned back to his shank and the band saw. “Oh dee doe doe doe.”

That morning he taught me to bone meat and cut fryers, and at noon I was wrapping the second case of fryers I had cut.

“Son, you bring a lunch?”

“No,” I said.

“Oh hell; you want to go to the Owl with me?” The Owl was the biggest bar and pool hall in town and stood as some kind of a shining mystique in a high schooler’s eyes. I could see myself again, in my dream, with the young thing, telling her about the Owl and lunch there with the old boy.

“You have to be pretty mature to go to the Owl, don’t you?” she’d say.

And I’d answer, “Sure do.”

“Hell, son, if you want to go to the Owl with me, you’d better speak up or starve,” the old boy said.

“Yes, why not.”

As we walked through City Center Parking Lot, and down the alley back of Eugene’s Paint ‘n’ Hardware, I thought of the only time that I had been to the Owl—the time I had gotten myself and John kicked out by not knowing the difference between pool and snookers. That was a year before.

“Hello Mike,” the old boy groaned as he walked through the door and sat at the bar stool. “It’s going to be a sweet roll and coffee again.”

“And you?” the bartender said after I took a seat beside the old boy.

I looked around myself for a list of food and prices, but there wasn’t one. Above the bar was a stuffed moose head with a long, dingy beard that the bartender’s head brushed every time he walked under it.

“I say, what about you?”

I stuttered and asked, “What’s good?”

“Good hell,” the bartender said, “it’s all good.”

Even though I was hungry, I ordered sweet roll and coffee, because I didn’t know what else they served in the Owl. The old boy ate without a word, hunched over his food, dipping the sweet roll into the coffee and slurping now and again. Behind the moose head, there was a long mirror that ran the full length of the bar, and in it I could see posters and calendars, most with big-busted girls, one with a girl squatting beside a NAPA bell-housing with a distributor cap in one hand, and there was a caption that I could read with difficulty that said, “As you can see, my parts are the BEST!” And the girl had a wide-eyed grin on her face. Next to her was a poster of a girl with faded white hair—the whole poster was faded and the girl looked fatigued—and she wore a bikini. Below the cardboard poster, there was a red string, and the caption read, “For a surprise, pull my string!”

I had lunch with the old boy in the Owl every day afterwards.

I went to school with John that Friday afternoon. Rulinda and Diann were on the front steps, standing in the afternoon sun, and as we drove up on John’s 750, Rulinda brought a notebook to her face to whisper something to Diann. Then they giggled and watched as we walked up.

As we walked, I dreamed of driving into the high school in a glittering Ford Mustang, and the girls would look admiringly at me.

Rulinda giggled again and said, “Hey, you guys, where you been?”

John strutted around and told them about his job driving trucks, and I stuck a thumb in my belt and asked them if they were doing any better today—and it worked for me too.

They looked confused. “Better than what?” Diann asked.

“Better than yesterday,” I said, laughing.

“No, really, where you been?” asked Diann.

“I’m a butcher for V.D.,” I said.

Rulinda looked astonished and asked if I were working for the county social services or something, and I said, “Nope,” still with my thumb in my belt, “I work downtown; I work with a girl who checks for V.D. and with a bunch of guys that are carriers.” Both of them blushed, and I puffed and strutted for a while. Finally I explained to them that V.D. stood for Valley Discount, the name of the store that Clever managed, the store that Thelma checked for, and the store that the old boy cut meat for. Then the girls had to go, and John and I stood around for a few minutes, there on the steps of the empty school in the afternoon sun, watching the buses rolling along the upper road—just standing there quiet, waiting to see if something would happen: but it didn’t, and we rode home.

Valley Discount was open until nine on Fridays, and most of the time, the old boy’d give me that shift while he went down to the Owl—told me that he didn’t have anything to go home to, so he preferred to be out and around. I worked one night there by myself while the old boy shot pool and drank. It was a warm evening, and during the slow hours, I stood out back of the store and listened to the leaves—they were just coming in full—as they rustled in the wind. It seemed to me that the leaves had an ideal existence; always together, dancing, almost like they were laughing in the wind. I heard the bell then and had to go into the shop to help a lady. Wanted a couple pounds of burger.

I went out again soon as she left. Sitting there on an overturned garbage can, I could hear Clever the Beaver up in his office working with the adding machine, and I knew he wouldn’t be crawling around looking through his peep holes, and I could hear the leaves and the wind. I felt immensely secure, while at the same time I felt immensely alone.

Except for the adding machine and the leaves, all was quiet until I heard the old boy dragging his feet through City Center Parking, and I could see him—he looked shorter in his short-sleeved, white shirt and his thin, black tie, shorter than he looked behind the counter with a bloody apron on, and I could see by the way he wandered that he was drunk. He walked slow, aimless—without determination. Closer, I could see that he had a pint in the hand with the bad finger, and his three good ones clutched the bottle tight. He recognized me, and snorted as he sat down on a peach crate and leaned aginst the cinder block. After a minute, he finished off the pint and dropped the bottle, and he snorted again.

“You any better?” he asked. His voice was raspier than usual—coarser.

“Not much.”

“Hell.”

The leaves were laughing again in the trees, and I could feel the soft wind. “I wouldn’t mind being a leaf.”

He looked at me for a second and said, “If s a hell of a world, son.” It startled me. “You work your life away—and it don’t do no damn good—it don’t get you nowhere. Hell.” The old boy lowered his head and rubbed his eyes with his stubby hands, and he looked tired. “I ever tell you about the time a can of Vienna sausage went bad on the canned aisle and exploded? Stunk bad. And Clever, he’d like to have jumped all over me—the bastard. I been cutting meat for fifty years; started when I was sixteen, and that Clever thinks my meat’s going to go bad. Hell.” The old boy rubbed his eyes again and breathed a heavy sigh. “Hell. For fifty years, and my three boys laying up there on the hill.”

We sat there quiet for a minute, and I listened to the leaves, and Clever up there beating away at the adding machine. I shifted on the garbage can and looked at the silhouette of the trees across the road.

“Yep, I’d like to be a leaf.”

“Why the hell for?” the old boy asked.

“It’d be nice,” I said, “to just hang around all day and make noises in the wind.”

The old boy leaned back again, against the cinder block wall, and he sighed again. “You’re wrong there, son,” he said. “It’d be hell. A leaf hangs there, just hangs there—and do you know what it hangs in?”

“No.”

“Nothing. That’s what it hangs in—nothing. It hangs there in nothing, doing nothing, and there’s nothing for it. It’d be hell to be a leaf.” He crouched and looked at the pavement between his legs for a long time. He sighed when he finally stood up. “Got to go, son.” I watched him as he swaggered down the sidewalk in his reeling gait, and he started singing when he was about a half block away. “Oh dee doe—Oh I once had three sons, dee doe doe, and they was twice my size, but now they’re on the hill, doe doe doe, and now their papa’s coming, oh-ho dee dah dee doe.”

I listened to the leaves until Clever’s adding machine quit, and I had to go inside.

I saw less of John in the following weeks, and summer came on—and the high schoolers left the school, and it was a lonely place. One night, early in the summer, I went out to the school and walked around the campus, and watched the bats that flew in and out of the butts of the rafters. It was still early; I had just left the old boy down to Valley Discount scrubbing the saw and the grinder. And the sky was pink to the west, pink around the Wellsville Mountains. The wind made an awesome sound, blowing around the corners of the buildings and up around the eaves.

When I got home that night, my mother told me. John had been coming over the canyon, his regular run, and he had taken a fit like he did in school, and he was dead.

The next morning, when I got to Valley Discount, the old boy was there already: there was a sale on lamb chops and he needed to be down early to open up for Eliason Brothers’ truck.

“Hell, son, it’s about time you was getting here,” the old boy said, and he scuffled into the fridge singing “oh dee doe doe doe.” As I stood there he scuffled back out of the fridge, grabbed two frozen legs of lamb, and started back. “What, you don’t feel like working today?”

“Not much.”

“Hell.” The old boy shuffled back into the fridge. He grabbed a string of link sausage and carried it to the glass case, where he had already set out the cold cuts, the deli, part of the fresh meat, and the bacon. “You just going to stand there? There’s some pre-cut sirlointips need the side loin trimmed, and I got just about enough for a grind of burger.” He walked back into the fridge singing about the three dogs that died the day he was born, and I took my apron from the hook and put it on; it was stained with blood. The old boy slid by me, and already the scraps of meat were accumulating on the tops of his black wing-tips, and he hefted another frozen leg of lamb—and his finger, jutting out abruptly from the rest, stood at attention.

In the fridge, I opened the box of pre-cut tips and took two out to the chopping block where I started trimming them with a boning knife. The old boy mumbled that he needed a hind quarter on the block, that he expected a run on boneless round, and I walked into the fridge and wrapped my arms around the quarter with its yellowed sinews, its thick layer of fat, and here and there a purple muscle. And I hugged the quarter to heft it—a good-sized quarter’ll weight most as much as a man—and it was cold and greasy between my arms. I thought of John, the school, the Owl, and as I lifted, my cheek pressed against the fat, and it was cold to me, and I could hear the old boy again, talking about the hill, and his boys, and that’s all there was to it. As I stumbled through the door with the quarter and flopped it on the chopping block, the old boy was singing, “Oh dee doe doe doe: Three dogs died, the day I was born; oh dee doe doe doe.” The old boy got his twelve-inch steak knife out and his steel, and he flashed the knife back and forth along the steel, the finger jutting out from the rest, with mechanical precision. I walked back to my block, back to my tips that needed trimming, and I sliced the meat carefully along the right contours.

That afternoon, sitting at the bar in the Owl, I picked up the paper and found an ad, the ad that I had looked for during the past months:

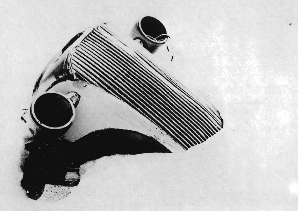

Excel. Cond. 1976 Ford Mustang.

Headers. New Rad. tires. Dual glass pax.

$1599 or best offer. 753-3615

I put the paper down to eat my sweet roll and drink my coffee. I could see the faded girl in the poster on the wall behind me—the tired-looking girl with the dead-white skin—and she looked back at me through the mirror behind the bar. After lunch I walked back across the City Center Parking lot toward Valley Discount with the old boy.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue