Articles/Essays – Volume 33, No. 2

A History of Dialogue, Part Two: Struggle toward Maturity, 1971-1982

After Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought was founded by Mormons at Stanford University in 1966, it attracted Latter-day Saint scholars from all over the United States, and soon its success surpassed the expectations of everyone involved. It mattered little that Dialogue was an independent publication without institutional ties or subsidies. As Mormon intellectuals flocked to sample the offerings of the new journal, subscriptions soon approached 8,000. With this phenomenal interest, the editors of the new journal proved early on that there was a need for a scholarly publication which would satisfy the spiritual and intellectual needs of faithful but thinking Mormons. It dealt with issues as no LDS publication ever had and found that, in creating an independent voice, Mormonism was ultimately the better for the exchanges.

Along with those who came to value Dialogue as part of their own quest, however, were many who came on board only out of curiosity. Once that curiosity had been satisfied, their subscriptions permanently lapsed. There were others who waited in vain for an official endorsement of Dialogue from LDS leaders. For them, the church’s announced position of neutrality was not sufficient.[1] Uncomfortable reading a Mormon-oriented publication that the church did not officially sanction, they, too, severed their relationship with the journal. By 1970, Dialogue was left with one managing editor, and the added responsibility began to take its toll. Publication soon fell behind schedule and, as a result of all of the above, subscriptions dropped to 5,000 before the end of the first editorship. Money finally became an issue as Dialogue struggled to keep up with rising printing costs, amassing a debt of several thousand dollars in the process.

Eugene England and G. Wesley Johnson, co-editors since 1966, left Stanford and their positions at Dialogue by 1971. England departed first, accepting a job at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, in 1970, and Johnson went to Africa one year later for a brief sabbatical.[2] With that, the Stanford experience came to a close.

The decade following the end of Dialogue’s first editorship witnessed a move into uncharted territory. It was, in fact, another decade of pioneering. By the end of that decade, Dialogue still boasted only a small readership, but a much more committed readership. The journal was financially healthy, seemed permanently established, and was—almost— back on schedule. Ironically, it was during its worst moments of despair that Dialogue’s message was most relevant. Not all ears welcomed that voice, however, and with the dawning of the eighties, anti-intellectual sentiment became more vocal in the institutional church. This trend would not reach its peak for another decade, however, allowing Dialogue and the publications and organizations that followed to become a safe haven for those who valued “the life of the mind in all its variety.”[3]

III. 1971-1976: “In the Valley of the Shadow”

I would be terribly disturbed at the prospect of Dialogue “going under.” I too am mystified at your seeming inability to get more subscriptions. . . . I will of course, keep asking all my friends the Dialogue “golden question.”

—Armand L. Mauss to Robert A. Rees, 6 January 1973

I have made an in-depth study of content and form through the last ten years, and I would put Rees’s performance up against anybody’s, considering the great odds under which he worked.

—Mary L. Bradford to Robert R Smith, 10 February 1977

Before he left Stanford in 1971, Wesley Johnson asked Robert Rees of the English department at UCLA to take over the Dialogue editorship. Rees had worked closely with the Stanford team from his home in Los Angeles, eventually becoming part of the editorial staff. As England re calls, he and Johnson had been “grooming” Rees for the job.[4] Rees accepted the offer and assumed the editorship of Dialogue on 1 September 1971.

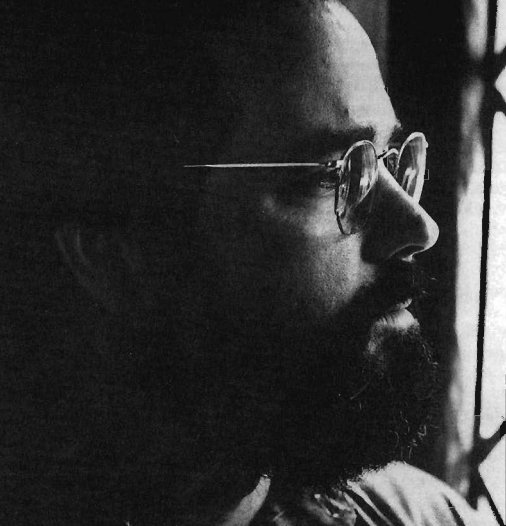

Despite inheriting a journal that was behind schedule and in debt, Rees’s enthusiasm never waned. A1960 graduate of Brigham Young University, he had earned his Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin in 1966, the year Dialogue first appeared. By the time he began his own editor ship, he and his wife, Ruth (Stanfield), had four young children, ages 3-10, and he was six years into an appointment as assistant professor of literature at UCLA. Active in the LDS church, he had earlier served two years in the Northern States Mission (1956-58). Rees’s first contact with Dialogue occurred when he received a flyer in the mail in late 1965. Not only did he immediately subscribe, but he offered to aid the fledgling publication in any way that he could.[5] Looking back to the day when he received the first issue, Rees once recalled “the excitement with which I opened it and devoured it in one sitting. I suddenly felt a renewal of faith in myself and in my fellow Saints.”[6]

In the ensuing years, Rees made good on his offer to help, serving both as book review and issue editor toward the end of the England-Johnson tenure, and guest-editing a special issue (with Karl Keller) on “Mormonism and Literature” (Autumn 1969). Rees’s remaining “deeply committed to the journal”[7] showed that no one was better prepared to take over the reins.

Rees’s deep commitment was tested many times in the days ahead, however. For the next five years, he would cope—often alone—with obstacles that seriously threatened the future of Dialogue.

The Move South

Because Rees had previously worked with the Stanford team, he was aware that publication of Dialogue had fallen behind schedule long be fore he officially took command of the journal. However, he was surprised to discover the size of the backlog of unread manuscripts that awaited him. This alone guaranteed that delays would continue in Los Angeles. In addition, costs of printing the journal, which had begun to escalate by the end of the previous editorship, continued to skyrocket. When Rees began his tenure, Dialogue still owed a large debt to its printer in Salt Lake City.[8] Rees wrote to Bud Nichols, owner of Quality Press: “I have been promised money [from the out-going team] for over a month and have yet to see one cent. I have been paying for our operation down here out of my own pocket in fact. As soon as the transfer is made, I will take a look at our financial situation and let you know how much we can pay you.”[9] In addition to these challenges, the many factors in volved in moving Dialogue to Los Angeles and establishing the offices guaranteed that the journal would remain behind schedule and in debt for the foreseeable future.

Early on, Rees secured office space for Dialogue at the University Conference Center across from the UCLA campus; it would later move to an office in nearby Westwood Village.[10] However, he did not enjoy the same benefits as had the founding staff in Palo Alto. The earlier editors had been invited to occupy space on the Stanford campus, free of any expenses.[11] Rees was not as lucky. Although he negotiated an acceptable rental rate for the Los Angeles office, the expense added strain to Dialogue’s already tenuous budget.[12]

Other aspects of the move to Los Angeles also created some tension. During that summer, Rees found himself at odds with the former editors over his intent to move the editorial office to Los Angeles. Everyone agreed that the office needed to be moved from Palo Alto, but Wesley Johnson, Eugene England, and Paul Salisbury—three of Dialogue’s founders now serving as advisory editors—favored relocating it to Salt Lake City, where several editorial assistants resided. If all the manuscripts were edited in Los Angeles, the founders reasoned, that setup “would leave [the Salt Lake City group] with crumbs.”[13] Rees countered in a letter to all three that it would be impossible for him to manage the journal if he could not be near his own editorial staff. Besides, Los Ange les could provide equal talent: “I feel that there is definite support for the editorial office here,” Rees insisted. Finally, Rees was also concerned about ongoing interference from the former editors. In the same letter, he writes:

I sense that you are reluctant to surrender control of the journal, and yet, I don’t feel I can accept the major responsibility for the journal without being given the authority and support to do the job according to my own standards. . . . If I am to continue to have a major part in the publication of Dialogue, I have to have people I can rely on and people who are close enough for me to have some kind of control over.[14]

Wesley Johnson, responding on his own, noted Rees’s obvious frustration and proposed a compromise. He suggested that the business and publication offices remain in Salt Lake City under BYU professor Ed ward Geary, while the editorial office would transfer to Los Angeles, under Rees, who would serve as “executive editor.” Johnson wrote: “I for one am impressed with the kind of talent pledged in L.A., although this has been questioned in SLC [Salt Lake City].”[15] By September, however, Rees and his advisors reached a different compromise: There would be two editorial staffs, one based in Los Angeles and the other in Salt Lake City. The business office would also be housed in Los Angeles, but the subscription office would remain at Stanford.[16]

This arrangement gave Rees the control he needed as editor and allowed Geary and his Utah staff some input in the selection of manuscripts. A September prospectus declared the new policy: “All manuscripts submitted to Dialogue are initially screened by the Los Angeles editorial staff. Those manuscripts potentially publishable in Dialogue are then carefully and closely evaluated by the editorial staff in Los Angeles and Utah and at times by members of the National Board of Editors.”[17] By making this change, Dialogue would scale back the use of the editorial board, a move Rees saw as an improvement:

During our first years manuscripts submitted to Dialogue were sent out to at least three members of the editorial board for review. Some members of the board were very punctual and efficient and returned the MSS [manuscripts] in a short period. Others either let them mold in their desks or were so ex cited about them they loaned them to friends and never got them back. It was perhaps a necessary process during those formative years. . .[but the] main problem with this procedure was that it took an inordinate amount of time to process some MSS. (We wrote rejection letters this past week on two MSS received in 1968!)[18]

A new six-step method of processing manuscripts was devised with the hope that it would create greater efficiency:

1. MS [manuscript] comes into the Dialogue office and a letter of acknowledgment is immediately sent.

2. MS is read within one week by a member of the Los Angeles editorial staff to determine if it is worthy of consideration. If it isn’t a rejection letter is written.

3. If worthy of consideration (which means that it is not totally without re deeming quality), a copy is made and sent to the Salt Lake-Provo editorial group (headed by Edward Geary of BYU), who sends back a written recommendation or evaluation within six weeks. At the same time the MS is read by at least three members of the Los Angeles staff.

4. If the staff (in Los Angeles or Salt Lake-Provo) feels an outside opinion is needed, the MS is sent to members of the board of editors or to outside experts.

5. When the recommendation is received from the Salt Lake-Provo group the Los Angeles group meets and makes a decision. It should be noted that final responsibility for accepting manuscripts necessarily remains with the editor, including special guest-edited issues.

6. If the MS is rejected, a letter is written. If it is accepted, a letter is written with an indication as to when the MS is projected to appear. A personal data form is also sent to the author at this time. If the MS is accepted with revisions, a member of the Board of Editors is assigned to work with the author in getting the MS into acceptable shape.[19]

In addition to redefining the role of the Board of Editors, a Board of Advisors was added to the operation. Its purpose was to “[advise] the editorial staff and the Board of Trustees on all affairs of Dialogue. . . . The Board also has a primary function of raising funds for the support of Dialogue.” The Board of Trustees, formed during the final year at Stan ford, would remain to help “direct and control the affairs of the Foundation.”[20]

Although Rees had assured the former editors that he would have an able staff in Los Angeles, assembling such willing hands took longer than anticipated. Hence, as Rees jokes, he was “chief cook and bottle washer” during the earliest months of his editorship.[21] He recalls: “Slowly I began to assemble a cadre of volunteers who helped enormously.”[22] The Los Angeles staff at the time of the first issue included as sociate editors Kendall O. Price, Brent N. Rushforth,[23] Gordon C. Thomasson,[24] and Frederick G. Williams III; assistant editors Mary Ellen Mac Arthur and Samellyn Wood; and business manager C. Burton Stohl.[25] Soon Rees would be joined by others: Fran Anderson and David J. Whittaker, assistant editors; Thomas M. Anderson, business manager (Stohl would be named financial consultant); Chris Hansen, management consultant; and Barbara White, executive assistant. Kathy Nelson would soon replace Linda Lane as secretary.[26]

The Utah Editorial Team

As mentioned earlier, the Salt Lake City-Provo editorial group was headed by Edward A. Geary, an English department faculty member at BYU. Geary had been a graduate student at Stanford when Dialogue was founded and served from the beginning as an editorial assistant. In 1967, he took over the duty of manuscripts editor when Frances Menlove, one of the five original founders of the journal, left Stanford and moved with her husband to Germany.[27]

Despite intense deliberations that went into the plan laid out in the 1971 prospectus, the actual splitting of editorial duties between staffs in Los Angeles and Utah was never fully realized. As Geary puts it, his ” ‘Utah team’ was mostly a fiction,”[28] although it did include Paul Salis bury, by then teaching at Utah State University, and Richard H. Cracroft of BYU.[29] Far from dividing the work as envisioned, Geary insists that he and his staff had lesser involvement: “[I] tried to solicit manuscripts in Utah. We had an annual board meeting at conference time. Pretty much everything else happened in Los Angeles.” Since Rees and his local staff handled most of the affairs of the journal, Geary’s duties consumed only a few hours of his time each week, and very little space. “The Provo ‘office’ was a drawer in my filing cabinet,” he jokes.[30] One duty assigned to the Utah team was overseeing theme issues.[31] With most of the work being handled by Rees and his staff, Geary’s title was officially changed to that of associate editor in 1973 (he was also made book review editor at this time). “Probably [this move] was simply a recognition of the reality,” he says.[32]

Late Issues, Shrinking Subscribers

With Dialogue already behind schedule when he began his tenure, Rees faced a difficult challenge. The spring and summer issues of 1971, although several months late, were at press by early November, and would be mailed before the end of the month. The plan was for the fall issue to follow in January 1972.[33] However, further delays caused by con verting to a new computer program forced the fall issue to be combined with the winter release, thus becoming the first double issue in Dialogue’s publishing history.[34] Although it did not appear until June 1972, this combined issue was a blessing, given the strained finances. In a letter to former editors, Rees wrote: “According to my calculation we should be able to save approximately $5,000 by combining these two issues and I doubt that we will have much adverse reaction.”[35] Indeed, neither the Dialogue correspondence nor the printed letters to the editor in follow-up issues reveal any subscriber complaints.

The chronic tardiness of the journal did not escape the watchful eye of the post office, however. A letter from the Salt Lake City Superinten dent of Postal Services, T. E. Littlefield, warned that since “Dialogue is not being published and mailed in accordance with its established quarterly frequency, it is necessary that a determination be made regarding the continuance of your second-class mail privilege.”[36] Rees had also missed a deadline for sending in a “statement of ownership.” He assured Littlefield that the problems were due in part to being “in the throes of reorganization” and promised that the situation would soon be rectified: “Our organization is now reorganized and stabilized and as soon as we are back on schedule, we should have no difficulty in meeting your re quirements.”[37] However, Rees again forgot to send in the required statement, and on 18 November Littlefield wrote back: “You have failed to comply with this requirement and according to postal regulations, your publication may not be mailed at second-class rates of postage after ten days from this date or until such time as you come into compliance.”[38]

Although eventual improvements in Dialogue’s mailing schedule re stored its second-class privileges, the journal would remain on shaky ground with the post office. Four years later, after falling behind sched ule again, Rees would report that “Dialogue is in danger of losing its second-class mailing permit and the post office has insisted that we get back on schedule.”[39]

Rees acknowledges that delays in publication “eroded some of the confidence in the journal,” and subscriptions continued to decrease as a result.[40] Although active subscribers had already dropped significantly before Rees took over the editorship, he informed a staff member that the problem was becoming a Catch-22:

The situation is serious in that by the time we mail two issues at the end of the month [November 1971] we will owe the printer $15,000. Before we can publish another issue he must be paid and until we get back on a regular publishing schedule we will continue to lose subscribers. As they used to say on the farm, we are between a rock and a hard place.[41]

Four months later, subscriptions had dropped to 3,800. A year later, they numbered only 2,000.[42] Thus, it was left to Rees not only to manage the journal, but to save it as well.

It was during this trying period that Edward Geary asked the crucial question: “Is Dialogue Worth Saving?” This was the title of an essay he wrote and circulated to supporters of the journal in late 1971. “Is its survival in danger? The answer is an emphatic but not unqualified yes. Dialogue is not going to fold tomorrow.” However, it would not survive without help: “With support from our friends we should be back on schedule by next spring. Support from our friends is essential, however, because the expense of printing and distributing these next three issues will stretch Dialogue’s resources to and beyond the breaking point.”[43]

Indeed, money was more crucial now than ever. Geary continued: “Dialogue has been a hand-to-mouth operation from the beginning, but in the last three years the mouth has required more than the hand could provide.” It would take a larger and more committed subscription base to prove that Dialogue was still relevant: “Obviously, any satisfactory solution will require great effort by many people, and it seems appropriate therefore to examine the question of whether Dialogue’s survival justifies such efforts or whether it should be allowed to die quietly.”[44] However, for Rees and a committed staff, a peaceful passing was not an option.

Dialogue Chapters and Fund-raising

In response to the dire circumstances described by Geary, the Board of Trustees set two goals early in the Rees tenure: (1) raise money to cover current needs, and (2) increase subscribers to 10,000. Through do nations and new subscriptions, the trustees hoped to raise $25,000 by June 1972. If these goals could be realized, Dialogue would become self-sufficient. If the larger subscription base could be maintained, that status would continue.

The plan of rejuvenation hoped to raise money from people everywhere, and throughout the fall and winter of 1971-72, supporters began forming “Dialogue Chapters” in several cities throughout the country. “I am sure we don’t want anything too elaborate,” wrote Rees to some prospective chapter heads, “but perhaps if each of you were to invite two or three couples who are interested in helping Dialogue that would be sufficient.”[45]

The trustees gave each chapter the responsibility of raising $1,000. By January 1972, their efforts began to bear fruit. Rees wrote Wesley Johnson: “The response so far has been quite good in some areas (New York, Salt Lake City, Logan, and Los Angeles) but rather disappointing in Phoenix, Chicago, Boston, and Palo Alto.”[46]

That same month, Rees announced that the chapters had raised $10,000. “Except for one $1,000 contribution and several of $200, these contributions have been $100 or less. It is gratifying to know that so many people are willing to invest in Dialogue.“[47] Soon, several large do nations by concerned individuals provided even more energy and a needed boost to the campaign. Mary Bradford, living in Arlington, Virginia, had solicited J. Willard Marriott, owner of the national hotel chain, who responded by sending her fifty shares of stock in the Marriott Corporation. She informed Rees: “This will amount to about $2,500.”[48] Also, Mormon philanthropist O. C. Tanner donated $1,000, while promising to make it an annual contribution.[49] Two weeks later, with the help of Leonard Arrington, G. Eugene England, Sr., the father of former Dialogue editor and founder Eugene England, made a $5,000 donation. In a letter of thanks to Arrington, Rees wrote: “That is the most significant contribution we have had and I am thankful for your help in securing it.”[50]

By April 1972, the chapters had raised $17,000, and things began to look better for Dialogue. When John Dart of the Los Angeles Times ran a story in May 1972 about Dialogue’s move to Southern California, it was entitled, “Brighter Outlook Seen for Mormon Magazine.”[51] In a letter of appreciation to Dart for his “fair and well written” article, Rees was happy to report that this publicity had brought in a dozen new subscriptions in just the nine days since the piece had appeared.[52]

Getting Back on Schedule

Since Dialogue was still lagging behind in its publication schedule, many subscribers began to wonder if the journal had indeed folded. When six months passed without the release of another issue, one sub scriber assumed the worst: “It is too bad Dialogue must fail. The stated purpose of Dialogue was a wonderful dream.” Mourning its supposed death, the writer suggested with sadness that perhaps it was “an act against God to look facts squarely in the face.”[53] Rees assured this concerned supporter that despite some difficulties, Dialogue was still in business:

Your letter of May 24 prompts me to respond with a paraphrase of Mark Twain’s. Upon hearing from the newspapers the report of his demise, he said, “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” The report you heard about the death or failure of Dialogue is also greatly exaggerated. Dialogue is not only surviving, it is almost at the point of profiting.[54]

Despite Rees’s optimism, however, people on the staff also began to wonder. “Where the heck is the magazine?” asked Mary Bradford. Rees responded that current delays were due to a “long series of problems we have had with the printer in Salt Lake City since January [1972].”[55] Consequently, Rees contracted with the Ward-Ritchie Press in Los Angeles, “one of the best in California,” as he explained to editorial board member Richard Bushman, adding that “we are delighted with the prospects of a printer who is just down the street instead of 700 miles away.”[56] Rees estimated that it would cost $500-$l,000 less per issue to continue to pub lish in Salt Lake City, but he was optimistic that this change would allow him to reestablish a reliable publishing schedule.[57]

The change did, in fact, pay off. Through exhausting labor, the Los Angeles team managed to publish seven issues between November 1971 and December 1972, nearly catching the journal up to schedule for the first time since 1969.[58]

Other factors also helped this accelerated schedule. Two of the issues were theme-centered and edited by outside guests, taking a tremendous burden off Rees. The first (discussed later) was a women’s issue overseen by a group in New England (Summer 1971). The second, a special issue on “Mormonism in the Twentieth Century,” was edited by James B. Allen of BYU (Spring 1972).[59] This issue also included special tributes to Mormon president Joseph Fielding Smith, who had died the previous July. Rees later published an offprint of these tributes and mailed copies to stake presidents throughout the church in an attempt to give Dialogue some positive exposure.[60]

Also contributing to the effort to get back on schedule was Rees’s decision to cut down the size of the summer and autumn 1972 issues to 96 and 88 pages respectively. Writing to a concerned subscriber about these smaller issues, Rees explains: “I note your remark about the thinness of our most recent issues. That is partly due to economics. Dialogue is, as usual, struggling financially, and it takes a lot less to publish a ninety page issue than some of the 160 or 170 page issues that we published in the past.”[61]

Appropriate to its mailing late that December, the autumn 1972 issue focused on Christmas and included Samuel Taylor’s delightful personal reminiscences, “The Second Coming of Santa Claus: Christmas in a Polygamous Family.”

Rees also cut costs in other ways. Since 1967, all General Authorities had been given complimentary subscriptions to Dialogue. Aware that some within the hierarchy were critical of the journal, Rees sent an inquiry asking who still wanted to receive it.[62] Those who specifically asked not to have it could cancel their subscriptions. Some asked to be removed from the list; others wanted to keep active subscriptions.[63] Such inquiries would be made again in later years.

The Women’s Issue

As subscribers received the first two issues released by the Los Angeles team in late 1971, one certainly stood out. The women’s issue, dubbed the “pink” Dialogue because of the color of its cover, had had its genesis in the summer of 1970, over a year before Rees’s tenure began. Eugene England had visited Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July and met with two local women, Claudia Lauper Bushman (who lived in Belmont) and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (who lived in Newton Center).[64] Bushman remembers walking with England and Ulrich on the Harvard campus one evening and pausing near the Widener Library: “I just blurted out that there should be a women’s issue of Dialogue and that we had a group who could put it together.” According to Bushman, England liked the idea: “I expected more of a hard sell, but he just immediately agreed and said to go ahead with it.”[65]

Bushman and Ulrich had begun meeting with several women in their local circle the previous month and started discussing issues that concerned them. “The women’s movement was much in the air at the time,” says Ulrich. “We just wanted to see what, if anything, it had to do with us.”[66] Bushman recalls, “Mormon feminism was nowhere, but as the American movement took off … the culture of it spilled over into the church.”[67] Thus, for this New England group, producing a women’s issue of Dialogue seemed inevitable and natural. Ulrich and other local women had already had publishing experience with the Relief Society sponsored guidebook, A Beginner’s Boston. Written as a fund-raising project for the Cambridge Ward, it appeared in local bookstores, sold over 20,000 copies, and raised several thousand dollars.[68] When Bushman and Ulrich received the go-ahead for the Dialogue project, they wasted little time. Bushman’s husband, Richard, soon wrote Rees, who was still serving as Dialogue’s issue editor: “Claudia plugs away on her Women’s Lib issue. The ladies have a great time getting together to discuss it. There are some good heads in the group, too. Should be an intriguing issue.”[69]

Even with its fast launch and strong support, both women recall several difficulties, from within the group and without, which nearly terminated the project. “We had tensions in dealing with each other,” admits Bushman.[70] Many of these problems would be natural with such an un precedented undertaking. “The issue seems pretty innocuous now, but the whole project was still pretty threatening,” insists Ulrich thirty years later. “Some women didn’t want to be associated with something that might make them seem critical of the church. Others thought we were not being bold enough. I think we were trying hard to be ourselves.”[71]

Bushman and Ulrich also had differences with Rees, whose editor ship began just months before the issue went to press in late 1971. Bush man remembers: “[Bob] thought our considerations of housework, etc., did not deal with the real issues for women in the church, which were priesthood and polygamy.”[72] Ulrich also recalls the tension: “This kind of thing is common in editing projects. There was a real misunderstanding, I think, about how much authority we had.”[73] In the end, however, Rees acquiesced, and the women produced the issue their way.[74]

As a means of soliciting manuscripts, the guest editors announced a “call for papers” in the summer 1970 issue of Dialogue (inside back cover), and the Los Angeles office soon forwarded submissions to the group in Massachusetts. Some articles came from local women, while other supporters also sent manuscripts. “There were endless talks about balancing the issue, getting this or that to go into it,” remembers Bush man. “The content mostly evolved, and I think it was quite representative of what we could get from a group not used to writing for such a publication.”[75]

The final product included an introduction by Bushman, “The Women of Dialogue,” and an essay by Ulrich, ‘And Woe unto Them That are with Child in Those Days,” a satirical look at the dilemma facing Mormon women in following church counsel to rear a large family, while at the same time being mindful of worldly concerns about over population. Juanita Brooks, in her essay, “I Married a Family,” touched readers with her personal account of raising a combined family while quietly nurturing her love of writing (she hid her typewriter under her ironing when company came, and even members of her own family were not aware of her 1950 definitive study, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, until after it appeared in print).[76] Cheryll Lynn May contributed “The Mormon Woman and Priesthood Authority: The Other Voice.” A selection of letters from single women, poetry, and the photographic essay, “Mormon Country Women,” gave further insight into the issues Mormon women faced, their diversity, and the voices that were emerging. Housework was addressed by Shirley Gee in “Dirt: A Compendium of Household Wisdom.” The issue featured only one contribution by a man: “Blessed Damozels: Women in Mormon History” by Leonard Arrington.

The pink issue was the first public sign that a feminist movement within modern Mormonism had been born. Bushman insists: “I think the [pink] issue was true of the times in dealing with the real issues that affected us.”[77]

The hard work of the Boston group paid off. Bushman recalls: “I think people were surprised and generally pleased. We got many favorable letters saying how at last there was a woman’s voice.”[78] Rees later sent Bushman and Ulrich the judges’ statement of the fourth annual Dialogue prize competition, which awarded it “Special Recognition”: “The ‘Women’s Issue’ was one of the best collections—perhaps the very best— of worthy writing and brilliant editing in Dialogue history.”[79]

Soon, other projects followed. As Ulrich wrote ten years later, “The pink Dialogue was not responsible for this outpouring of women’s voices, but it did begin it.”[80] Arrington’s essay played a role in that, as Ulrich ex plains: “I think Leonard’s piece helped us see the importance of history.”[81] That realization led Judith Dushku to organize a class on nineteenth-century Mormon women for the Cambridge, Massachusetts, LDS institute in 1973. The class lectures later formed the chapters of Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah, edited by Claudia Bushman in 1976.[82] While researching her own lecture for the same institute project that Dushku began, Susan Kohler discovered at the Widener Library a set of the defunct Mormon feminist magazine, Women’s Exponent, which ran from 1874-1914. With this forgotten voice serving as inspiration, a successor, Exponent II, was launched in the summer of 1974. Bushman served as its first editor with Ulrich and ten other women forming the editorial board.[83] The newspaper is still published quarterly out of Arlington, Massachusetts. “I suppose the pink issue gave us confidence that we could do more things,” says Bushman, reflecting on the energy that followed it.[84]

However, when asked what the pink issue did for Mormon feminism overall, Bushman is quick to answer: “Not enough.” Still, she adds,

It was a voice in the wilderness. I was always interested in the way that our little group of housewives with crying babies began to be taken seriously, one of the great aims of our lives. People talked about the Boston group as if this was indeed the genesis of an important movement. I have been interested in talking to women who were there at the time, but were too engaged in their own work to be involved with us. They later asked why they weren’t involved. Why hadn’t they been invited, although they certainly were at the time. What we were doing just didn’t look that important then. What I am saying is that these activities have now taken on a stature and importance beyond their relative importance at the time. Which is, of course, the way history gets skewed. We were present at an important creation.[85]

Dialogue and the Beginning of “Camelot”

Only a few months after Mormon feminism was reborn, the LDS church made an announcement that also got the attention of Dialogue readers. In January 1972, the church departed from tradition and ap pointed a trained professional to the office of church historian. Leonard J. Arrington, professor of economics at Utah State University, accepted the call from First Presidency counselor N. Eldon Tanner. From the inception of the office, only members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had held this post, the most recent being Elder Howard W. Hunter, appointed in 1970. By Hunter’s own admission, according to Arrington, “The Church Historian’s Office had done almost nothing to compile church history since 1930.”[86] Thus, with Arrington’s call, a new era of church history research and writing began.

This was especially exciting for Dialogue because Arrington had once been associated as an advisory editor and had published regularly in the journal.[87] In addition, Arrington received approval for two assistant Church Historians who were also academics: history professors Davis Bitton (of the University of Utah) and James B. Allen (of BYU). Neither was a stranger to Dialogue, and both, like Arrington, had published frequently in the journal.[88] Bitton was even working as book review editor at the time and in 1974 would begin serving on Dialogue’s editorial board.

Apostle Hunter was excited about the serious writing envisioned by the new team of professionals, telling Arrington, “The Church is mature enough that our history should be honest.” In his memoirs, Arrington continues:

[Hunter] did not believe in suppressing information, hiding documents, or concealing or withholding documents for “screening.” He thought we should publish the documents of our history. … He thought it in our best interest to encourage scholars—to help and cooperate with them in doing honest research. Nevertheless, Hunter counseled me to keep in mind that church members reverenced leaders and their policies. . . . If the daylight of historical research should shine too brightly upon prophets and their policies, he cautioned, it might devitalize the charisma that dedicated leadership inspires. I accepted Hunter’s counsel as a mandate for free and honest scholarly pursuit, with a warning that we must be discreet.[89]

Dialogue benefitted from the Arrington team as a dozen or so projects sponsored under the auspices of the historical department were eventually published in the journal. The first, “The Twentieth Century: Challenge for Mormon Historians” (Spring 1972) by James B. Allen and Richard O. Cowan, appeared in Allen’s guest-edited theme issue.[90] “Oh, it was exciting,” remembers Mary Bradford of Dialogue’s editorial board. “People thought they could [write] almost anything.”[91] Rees remembers it as “a wonderful time. Intellectuals were valued, trusted, and honored for what they could do.”[92] This excitement remained strong through the end of Rees’s term.

Arrington’s call came four months after former editorial board member Dallin H. Oaks was appointed as president of Brigham Young University. Noting the implications, one Mormon historian spoke for many when he declared it a day of “toleration and understanding” for those in volved with the journal: “Whatever [sic] shadow of doubt may have been cast on one’s loyalty to the Mormon Church through association with Dialogue . . . has certainly been dispelled by some recent events.”[93] Although the tide would later change, Arrington’s tenure has been dubbed “Camelot” for reasons remembered by assistant church historian Bitton: “It was a golden decade—a brief period of excitement and optimism.”[94]

Dialogue’s Dark Days of 1973

Despite success in fund-raising, improvements in the schedule, and publishing quality scholarship, efforts to increase Dialogue subscriptions for the most part failed. Rees believed this was due in part to misunderstandings about the journal, as he explained to Arrington: “As strange as it may seem, Dialogue still suffers from myths and misconceptions that many hold about its purpose and design.” This was a problem Dialogue could hardly afford: “All this would perhaps be harmless enough if Dialogue were not dependent upon new and continuing subscriptions to sustain its efforts.” Lacking an adequate remedy for the situation, Rees continues:

In spite of the fact that we have published seven issues during the past twelve months and tried to publish a quality journal, subscriptions have not reached the break-even point and, in fact, have fallen considerably below our expectations. We don’t know why, but certainly a contributing factor is the ignorance about and distrust of Dialogue that seem to abound in the Mormon community.[95]

Rees further explained the persistent problem to Eugene England: “One of the things that we have to overcome is ignorance of Dialogue and also fear from people who feel that it is an apostate journal.”[96] Writing another supporter four days later, it seemed to Rees that the situation could not get any worse as he now considered the possibility that Dialogue’s days were numbered:

The fact of the matter is that Dialogue has not flourished in the last several years and we are mystified as to why this is the case and we are striving diligently to overcome it. There is a very real danger that if something is not done in the near future that Dialogue will have to cease publication. I person ally will consider that a great tragedy, since I feel that Dialogue plays an extremely important role in the Mormon community.[97]

More Chapters, More Money

There was no time to waste as Rees was forced to revitalize interest in Dialogue. Subscriptions were down, and Rees became even more frustrated about the journal’s reputation. With dwindling support, the most pressing need, once again, was money.

Since the Dialogue chapters had earlier met with astonishing success, Rees and his staff began planning an encore.[98] Between January and May 1973, twelve new chapters were organized or revitalized, and each began operating with varying success. Overall, the commitment of supporters was once again impressive: The Palo Alto chapter, after a poor performance previously, raised over $1,000 by May, with a promise of more by the beginning of July; the Phoenix chapter sent in $500 “and is moving strong;” George D. Smith, a New York Mormon who headed the Dialogue group there, sent in fifty new subscriptions; Mary Bradford, still in charge in the Washington, D. C, area, filled her home with sixty-five supporters in April; Eugene England managed to get one hundred new subscribers and raise $1,000 in Chicago.[99] Although failing to reach the goal of $25,000 by the end of 1973, Rees was happy to report that $20,000 had been raised through this intensive campaign. In fact, as the journal’s finances began to recover early in the campaign, Rees became Dialogue’s first paid editor, receiving a salary of $500 per month.[100]

Because the chapter chairpersons had proved to be tremendous assets through these fund-raising efforts, they were soon installed as new members of the Dialogue Advisory Board.[101]

An Unlikely Endorsement

Rees was understandably concerned about the many misunderstandings about Dialogue, but he was surprised and heartened to read an endorsement of two past issues of the journal by the associate commissioner of education for the Church Education System. In the April 1973 issue of the seminary and institute publication, Growing Edge, Joe J. Christensen recommended that CES faculty read the Mormon History Association issue, guest edited by Leonard Arrington (Fall 1966), and James B. Allen’s recent issue on twentieth-century Mormonism.[102] Grateful, but believing such a limited endorsement was insufficient, Rees wrote Christensen and asked him to encourage more reading of Dialogue by CES personnel.[103] To this, however, Christensen was hesitant:

I am well aware of the fact that Dialogue has published some very significant articles and essays during the past several years, along with what has been some controversial material as well. What a strength it would be if we could amplify the former and de-emphasize the latter.[104]

Rees responded promptly, and his sensitivity to the perceptions of Dialogue is apparent:

I was surprised to see your dichotomy between significant articles and controversial articles, and your suggestion that it would be better if Dialogue published fewer controversial articles. It seems to me that some of the most controversial articles we have published have also been among the most significant. I would also say that under my editorship, at least, Dialogue has not sought for controversy in and of itself, but some subjects by their very nature are controversial. It seems to me that this is no reason to shy away from them or to refuse to talk about them. In fact, in the history of the Church from its inception to the present, there has been a good deal of controversy and that controversy has often been very helpful to the Church. Joseph Smith himself was an extremely controversial person, and I think it is important for us to keep that in mind.[105]

This philosophy would continue to guide Rees through the remain der of his tenure. In fact, two of Dialogue’s most controversial, yet important, issues would soon appear.

The “Negro Doctrine,” Round Two

The Los Angeles team published the first of these landmark issues as Dialogue passed through its most serious financial struggle yet, and Rees was hopeful that reader interest would increase: “We hope the next issue, one of the most significant which we will have published, will do something to stimulate subscriptions.”[106]

Indeed, the Spring 1973 issue featured Lester Bush’s “The Mormon Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” detailing the origins and his tory of the (then) current Mormon policy of denying the priesthood to black males. Providing the most thorough study of the policy to date, Bush examined all available primary sources and concluded that the priesthood ban did not begin with Mormon founder Joseph Smith as commonly taught, but had its origins with his successor, Brigham Young. Privately announced by Young in 1849, the ban was explained in various ways by church leaders over the next 120 years. Bush identified five periods of development in documenting Mormon justifications of the pol icy. In analyzing church leaders’ attempts to explain the ban, Bush refuted popular doctrinal and scriptural rationales.[107] In his essay, Bush, who was serving as a medical doctor in the American Embassy in Vietnam, expanded a thesis he had first presented in a 1969 book review of Stephen G. Taggart’s Mormonism’s Negro Policy: Social and Historical Origins.[108] This earlier essay had also been published in Dialogue.[109] His 1973 follow-up article is remembered as one of the most important pieces ever to appear in the journal.[110]

Rees was not oblivious to possible repercussions in publishing the essay. “It is, of course, a potentially explosive issue, and undoubtedly there will be many people displeased at our efforts, but the time is long overdue, it seems to me, for us to publish some significant work on this subject.”[111] Rees’s words were prophetic as Bush’s ground-breaking research immediately troubled some in the church hierarchy. Former editor Eugene England spoke to one church leader who believed that publication of the article “would stir up an issue which was physically dangerous to the General Authorities.”[112] In fact, rumors were afloat, as one Mormon scholar remembered, that some church leaders “were on the hit lists of some black extremist groups who were set on killing them or ‘roughing [them] up’ during demonstrations.”[113]

In 1999, Bush published an account of events that led to the publication of his study.[114] Since his earlier (1969) response to Taggart, Bush had continued to research primary source material on the origins of the Mormon black policy and, by 1972, had produced a 400-page Compilation on the Negro in Mormonism, which he gave to certain friends. One such friend, Janath Cannon, wife of Swiss mission president Ted Cannon, told Bush that she planned to pass his research on to Apostle Boyd K. Packer during his upcoming visit to the mission, “and ask him what he thinks you should do with it.”[115] That act brought on a series of letters, tele phone calls, and meetings between Bush and Packer (discussed below) which would continue for over a year.

Meanwhile, Bush made arrangements with Rees to publish his research as an article in Dialogue and sent off his manuscript in March 1973.[116] Two months later, Bush wrote Rees: “On the recommendation of several close friends I have sent a copy (with the errors corrected) of my paper to the Church, and explained my plans regarding it.”[117] Two weeks later, Bush received, second-hand, a response from Packer that the Brethren ” ‘were anxious’ that I ‘not publish the material until after I had talked with a member of the Quorum of the Twelve.”[118]

The following day Bush called Packer from Vietnam. Packer encouraged Bush to delay publication “a few months, or maybe a year or more,” until the two could meet. “There was no suggestion of ‘don’t publish it.’ He seemed, if anything, to be avoiding a direct recommendation, or something that I might construe as telling me what to [do].”[119] Packer told Bush that a copy of his Compilation as well as his article had been passed on to the Historical Department for review although Bush later learned that historians there denied seeing it or having been told about it.[120] Packer and Bush met in person on 30 May and 1 June 1973. Packer stated several times that “it was ‘unfortunate’ that [Bush] had chosen to publish in Dialogue as this alone would give the article notoriety, and lead to its use against the Church.”[121]

Although Bush was not pressured against publishing the essay, Rees was. In fact, he was told he “would pay a heavy price” if it did appear in the journal.[122] He recalls an intense telephone conversation that occurred on 28 June 1973 with his close friend, Robert K. Thomas, academic vice president of BYU. When Rees assured Thomas that he was going to publish the article, Thomas warned of trouble. “The brethren will not be pleased with you for doing this,” he said. “How do you know?” responded Rees. “Have you spoken to one of the brethren about this?” Thomas denied he had, but claimed “that he knew nevertheless.” When Rees continued to press him, Thomas only revealed that he knew “from an unmistakable source, high up.” Stunned, Rees reassured Thomas that Dialogue had done everything possible to be responsible and balanced in publishing the essay, and that the article and copies of Bush’s research had even been sent to some of the general authorities in advance. However, according to Thomas, this would not make any difference:

He again warned me that publishing the article could prove costly to me. When I asked what he meant by this, he suggested that it could cost me my membership in the Church. I said I felt that if the general authorities were that concerned then one of them should call me and speak to me about the issue. I said that as editor I was trying to make a sound decision but that if it turned out that I was wrong, I hoped the brethren would forgive me. He said they would not. I replied, “If what you are saying is true, it disturbs me more than the denial of the priesthood to blacks does.”[123]

This situation created a dilemma for Rees. “Bush’s article contained information that was essential to a continuing dialogue about this issue and . . . not to publish it would have been not only editorially irresponsible, but, for me and my colleagues, morally indefensible.” In the end, Rees chose his conscience: “I was disturbed by the prospect that acting in what I considered a morally responsible way could cost me my member ship, but I felt that it was a risk I would have to run.”[124]

After the article appeared in September 1973, however, none of Thomas’s fears materialized. As Rees wrote to Bush one month later: “So far the only responses that I have had to the issue have been very positive. So far, no indication of a response from 47 East South Temple. Have you heard anything?”[125] Two weeks later, Rees reported: “Everyone feels that it is the most important thing we have published.”[126] The essay would soon win prizes for best article from both Dialogue and the Mormon History Association for 1973.

Knowing how sensitive the topic was, Rees arranged for the article to be followed by three respondents: Gordon Thomasson, Hugh Nibley, and Eugene England.[127] England’s essay, entitled “The Mormon Cross,” won honorable mention for the sixth annual Dialogue prizes. In a letter to England, Rees wrote: “You would be interested in knowing that a number of people have expressed to me personally the impact your essay had on them for good.” Rees was also aware of rumors claiming the article had damaged England’s career opportunities: “Someone told me that the essay may have cost you a job at BYU. I hope that that is not the case, but if it is then BYU isn’t worthy of you.”[128]

To promote this issue of Dialogue, Rees submitted an advertisement created by graphic designer David Willardson to the University of Utah’s Daily Utah Chronicle and Brigham Young University’s Daily Universe. It featured a photograph of a handsome black man with a caption containing the 1963 statement of Mormon apostle (and later president) Joseph Fielding Smith, which had long since embarrassed LDS liberals: ” ‘Darkies’ are wonderful people, and they have their place in our Church.”[129] As Rees explained to Bush: “Underneath is copy which turns that around in a very nice way so that it isn’t offensive, but I don’t know whether they will publish it or not.”[130] Rees tried to avoid any “political interference” by delivering the ad right before publication. “We almost made it,” he remembers. However, it was dropped after “an overzealous staff member” at the Chronicle complained to University of Utah president David Gardner. The BYU ad was also dropped, but for reasons not fully known. Bush later noted to Rees: “I can’t say that I was surprised that your projected advertisement was not carried. Considering the paranoia on the subject, it doesn’t seem possible that any format could have rendered the intro ‘inoffensive’ in Utah.”[131] Rees, however, has fond memories of his attempt to advertise this important issue of Dialogue. “It was really a wonderful ad,” he insists.[132]

The Science Issue

In July 1974, a second double issue of Dialogue appeared. Guest edited, its theme centered on science and religion. Although released later in the Rees tenure, the issue had its genesis much earlier. The idea of publishing on the subject was first introduced during a meeting Rees held in Provo around 1971. Rees needed a guest editor for the proposed project and immediately accepted the offer of James L. Farmer, an assistant professor of zoology at Brigham Young University.[133]

Farmer set out to produce an issue that would offer “a wide spectrum of topics in the hope that they would stimulate further articles in future issues.”[134] The result was diverse. Among the nine essays published was Edward L. Kimball’s interview with his uncle, Mormon scientist Henry B. Eyring. Farmer wrote at the time: “It has several very valuable anecdotes as well as comments which provide interesting insights into the man.”[135] Hugh Nibley, one of Mormonism’s most gifted and respected scholars, provided an essay containing early Christian ideas on the creation of worlds, while interviews with three anonymous scientists formed a piece entitled “Dialogues on Science and Religion.”[136]

The most controversial article was by BYU assistant zoology professor Duane E. Jeffery, “Seers, Savants, and Evolution: The Uncomfortable Interface.” In his essay, Jeffery summarized diverse interpretations of the scriptural creation narratives by nineteenth-century church leaders. More importantly, however, he chronicled twentieth-century clashes over organic evolution between such prominent general authorities as Joseph Fielding Smith and B. H. Roberts, making available little known pronouncements on evolution by the First Presidency.[137] Jeffery was meticulous. Farmer informed Rees that with last-minute changes Jeffery made to his manuscript, “his position [is] much stronger, mainly due to some new documents which have recently become public for the first time. This is especially true regarding the Joseph Fielding Smith-Brigham Roberts debates.”[138] Overall, Farmer was pleased with the resulting issue. “It was my opinion that I could defend anything I had chosen,” he recalls. Thus, “no one ever made any waves with me.”[139]

Evolution was a sensitive topic, however, and everyone involved could foresee potential trouble resulting from Jeffery’s article, as Jeffery himself knew: “We realized that we would be causing stress for some of the entrenched interests in the Church and at BYU who had been telling a very different story for years.”[140] Troubled by the fact that anti-evolutionist sentiment had been allowed to flourish in the church despite official pronouncements of neutrality, Jeffery felt he was aiding the church by publishing some forgotten viewpoints. For instance, the November 1909 First Presidency declaration, “The Origin of Man,” had long been regarded as “the official pronouncement against evolution.”[141] However, two later statements issued by the presidency declared or implied a much more open position. In 1925, prompted by the nationally publicized “Scopes Trial” in Dayton, Tennessee (John Scopes was a high school teacher on trial for teaching evolution, contrary to state law), the presidency issued a rather telling statement.[142] Although much of it repeated the 1909 “Origin of Man,” the presidency (Heber J. Grant, Anthony W. Ivins, and Charles W. Nibley) omitted all the anti-evolutionist paragraphs of its predecessor.[143] In April 1931, responding to the op posing views of Joseph Fielding Smith and B. H. Roberts on evolution, the First Presidency formulated an even clearer position of neutrality on such issues as the concept of death on the earth before Adam and the existence of beings termed as “pre-Adamites.” While their letter was not made public, it said in part:

The statement made by Elder Smith that the existence of pre-Adamites is not a doctrine of the Church is true. It is just as true that the statement: “There were not pre-Adamites upon the earth,” is not a doctrine of the Church. Neither side of the controversy has been accepted as a doctrine at all.

Both parties make the scripture and the statements of men who have been prominent in the affairs of the Church the basis of their contention; neither has produced definite proof in support of his views.

Upon the fundamental doctrines of the Church we are all agreed. Our mission is to bear the message of the restored gospel to the people of the world. Leave Geology, Biology Archaeology and Anthropology no one of which has to do with the salvation of the souls of mankind, to scientific research, while we magnify our calling in the realm of the Church. . . .[144]

Jeffery’s research pointed to a less rigid position than the 1909 statement implied, so “it was . . . clear that the story needed to be told. Every biologist still active in the Church knows the names of others who have left due to ‘intellectual estrangement.’”[145]

At least one general authority could not contain his displeasure, however. Speaking at a BYU devotional over a year and a half later, Apostle Ezra Taft Benson, then president of the Quorum of the Twelve, criticized what he called a “humanistic emphasis on history.” Then, while not identifying it precisely, he spoke directly of Jeffery’s article:

Most recently, one of our Church educators published what he purports to be a history of the Church’s stand on the question of organic evolution. His thesis challenges the integrity of a prophet of God. He suggests that Joseph Fielding Smith published his work, Man: His Origin and Destiny, against the counsel of the First Presidency and his own Brethren. This writer’s interpretation is not only inaccurate, but it also runs counter to the testimony of Elder Mark E. Petersen, who wrote [the] foreword to Elder Smith’s book, a book I would encourage all to read. . . .

When one understands that the author to whom I alluded is an exponent of the theory of organic evolution, his motive in disparaging President Joseph Fielding Smith becomes apparent. To hold to a private opinion on such matters is one thing, but when one undertakes to publish his views to discredit the work of a prophet, it is a very serious matter.[146]

Jeffery was shocked at Benson’s characterization of him and his essay, and more specifically by the accusation that he smeared the reputation of Joseph Fielding Smith. “In reality I had bent over backward to avoid that. There is much more to the story [pertaining to Smith] than has publicly been told.”[147]

On 4 June, Jeffery wrote BYU president Dallin H. Oaks in an attempt to get an audience with Benson:

I contacted President Dallin Oaks after the speech and requested help in making contact with President Benson, indicating that I had acted as honor ably as anyone could, that I had greatly underplayed the story as it had involved President Smith, and indicating that if President Benson had additional data which altered the story I would be most happy to publish a formal retraction.[148]

Oaks responded to Jeffery on 7 July: “I am hopeful and confident that with a little love and understanding and patience and patience and patience that these things will work out.”[149] Jeffery was discouraged from contacting Benson about the matter: “I was informed that they knew that I had the data but that President Benson had the pulpit, and if I did not wish to get denounced at pulpits all over the Church to audiences which I had no possibility of reaching, it would be best to just remain silent.”[150]

Jeffery’s college dean, Lester Allen, told Jeffery that although “Brother Benson probably wishes that you were not employed by the university,” the apostle “would regard any correspondence from you on the topic of evolution as a goad that would probably only serve to further strengthen his negative feelings. … I do not see that the letter could be anything but divisive.”[151]

Jeffery kept silent and, in retrospect, it was a wise move. Twenty-six years after being publicly criticized as disloyal by Apostle Benson, Jeffery continues to teach in the zoology department at BYU. “And yes, the paper did open further doors,” he says confidently. “I think the data of the paper (not necessarily the paper itself) can be credited also for the existence of evolution now being a required course for all zoology majors at BYU.” In fact, Jeffery and Dr. Clayton White received approval from church headquarters for their own undergraduate course in evolution, and several excellent evolutionary biologists can now be numbered among the faculty at BYU. “I’m confident [that they] would not be here had the [November 1909] First Presidency statement [on evolution] been the only one [known] in Church history. Knowledge of the others has unquestionably made a huge difference.”[152]

Saving the Journal

If publishing such ground-breaking articles was enough to ensure the success of Dialogue, Rees could have rested easily, but the need for money remained constant. Despite the recent success of the Dialogue chapters, Rees knew that continued fund-raising of this magnitude was impossible. Although subscriptions had increased, they failed to come in at the rate needed for the journal to become self-sufficient. Consequently, Rees and the executive committee finally made a difficult decision. Since the chapters had proved the existence of a core group which was willing to sacrifice for the success of the journal, but because annual operating costs were also approximately $30,000 above what subscriptions brought in, the committee decided that the only way to compensate for the small readership was a dramatic rise in the subscription price.[153] Rees had earlier increased it from $6 to $9 annually, then from $9 to $10. Effective January 1974, the price would double to $20. Rees justified the new rate in a letter to chapter chairpersons:

With your help we were able to raise $20,000.00 in contributions [in 1973], but we also feel that it is unrealistic for us to believe that we can continue doing this year in and year out. Therefore, we have placed the responsibility for the continuance of the journal squarely on the shoulders of our readers. I think one thing that may help is for you to educate people to the fact that many professional journals cost $20.00 or more, and that Dialogue is not re

ally out of line. But even if it were, if the idea is important enough for people who read it, then it will continue. If people do not value Dialogue to the extent of being willing to pay $20.00 a year for a subscription then perhaps it should not continue.[154]

To retain subscribers who simply could not afford to pay double for the journal, the $10 rate would still apply if “an extreme hardship” existed. However, those with higher incomes were asked to pay even more than the set price of $20. A renewal card sent to subscribers asked for the following:

Annual Subscription Rate $20

RECOMMENDED ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION RATE:

| Annual Gross Income | Rate |

| More than 20,000 | $25 |

| More than 30,000 | $30 |

| More than 40,000 | $40 |

Some subscribers were naturally upset. One responded angrily: “Only a Mormon would base a subscription rate on income. My Bishop will never know how much I make and neither will you.”[155] Rees answered one letter of complaint: “It was a painful decision in many ways, but we felt that [the] only way that the journal could really continue was to [quit] living from hand to mouth.”[156] To another upset reader, Rees responded that “all of our efforts to increase the number of subscriptions have met with very little success. There are far too many people who still feel threatened by Dialogue or who are afraid to read it for one reason or another.”[157] Amazingly, complaints were the exception, and by summer Rees was ecstatic about the results: “I might say that the decision to raise the subscription to $20 and on a sliding scale has been one of the best decisions we have made at Dialogue.” He added: “When I took over as editor three years ago, we were some ten to fifteen thousand dollars in the red. We are now that much in the black, and when [the next] issue is printed we will be able to pay it off immediately, something that we have never been able to do since the early years of Dialogue.”[158]

For now, it seemed, Dialogue’s troubles were over. Although Rees would still experience unwanted and unexpected hardships as editor, never again would he be faced with the prospect of Dialogue folding while under his care.

The Founding of Sunstone

As Rees experienced both the highs and lows of publishing an independent Mormon journal, he may well have doubted that anyone else would have the energy to start a new one, but for a group of young Mor mons in 1974, the energy was there. Scott Kenney was a student at the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley, who, with several of his peers, made preparations for a new publication. Not feeling confident enough to write for Dialogue, Kenney envisioned his publication as an outlet for students: less intimidating and thus more attractive to a younger crowd.[159]

Rees developed a relationship with Kenney and his staff when they visited Rees at his home in Los Angeles.[160] In fact, it was Rees who suggested a name for the journal, Sunstone, to replace Kenney’s first choice, Whetstone. Rees’s reasoning was simple: The sunstone was “a wonderful symbol from the Nauvoo Temple, which works both in reference to the Son of God and that of a symbol of light,” while Kenney’s idea of a whet stone could be misconstrued as “sharpening our knives against the Church.”[161] The group came to favor Rees’s suggestion as well. By November 1975, the first issue of Sunstone was off the press and another Mormon publication was born.[162]

Rees was happy about the prospects of a student-oriented publication and never felt any real competition between Dialogue and Sunstone. From his first meeting with Kenney and his staff, Rees promised to help by sending manuscripts their way. In February 1975, Rees presented the Sunstone staff with twenty-five manuscripts that had been rejected by Dialogue.[163] Dialogue associate editor Mary Bradford later wrote Rees regarding an encounter with a member of Kenney’s staff, and Bradford was impressed: “I spent half a day with Peggy Fletcher this week. I do wish we had her on our staff! Whatta gal! They have 650 subscriptions, and three people are doing the work. She edited the second one alone.” Bradford probed further: “I asked her why she wanted a magazine and she said she thought Dialogue too stuffy, too academic and too elitist.” Bradford was surprised by Fletcher’s assessment and concluded that Fletcher had little to back up her view. However, “[we] hit it off very well, and decided to help each other as best we could.”[164]

Published letters by the founders of each publication in each other’s journal symbolize the cooperative relationship that developed. Kenney took the opportunity to announce his forthcoming periodical in a letter to the editor in Dialogue, and Eugene England, in turn, wrote a letter of counsel to the editors of Sunstone, which was printed in its premier issue.[165] During the next quarter-century, as both publications matured and veteran scholars began to publish in both, the original student emphasis of Sunstone was forgotten. Some tensions later arose between the two publications as the editors of each began to compete for papers, especially those presented at the annual Sunstone Theological Symposium, beginning in 1979. However, a supportive spirit eventually developed and continues to this day.[166]

Commitment to Quality

When summing up his editorship, Rees later admitted that “quality has been so important to me, that I sometimes let other matters, such as deadlines, suffer.”[167] This commitment to quality led Rees to seek contributions that would allow the journal to be appreciated by Latter-day Saints across the spectrum. Like his predecessors, however, his efforts were not always successful. In 1971, for example, he proposed an interview with former First Presidency member Hugh B. Brown, who had resumed his position in the Quorum of the Twelve after the 1970 death of church president David O. McKay. Some of Rees’s questions for Brown were intriguing. Regarding Christ: “What makes you certain of his existence and divinity?” Regarding the issue of blacks and the priesthood: “Do you believe Joseph Smith was told by the Lord not to give Negroes of African descent the Priesthood? Did he [Joseph Smith] initiate the practice, or did Brigham Young? What evidence do we have? Why do you think the Lord has us continue this practice?”[168] Three years later, in the fall of 1974, Rees and Eugene England interviewed Brown in his [Brown’s] home. Unfortunately, the aged apostle felt that his answers were too candid for publication and feared offending his colleagues in the Quorum of the Twelve. Thus, the interview was never made public.[169] With Brown’s death the following year, Dialogue lost its most ardent supporter in the church hierarchy. Naturally, Rees published a tribute to the church leader soon after his passing.[170]

Rees also took the opportunity of inviting First Presidency counselor Harold B. Lee to contribute to the journal. An exchange of letters between Lee and Rees came about after Lee had made an inquiry about Rees to Rees’s stake president, John K. Carmack. As Rees remembers the situation: “President Lee commented that I was a member of John’s stake and he wondered if John could persuade me to use my talents to support BYU Studies (with the clear impression that such service would be in lieu of my work for Dialogue).” Rees did not learn of the conversation be tween Lee and Carmack until after Lee’s death, and he was understand ably surprised when he received a letter from Lee.[171] Although Lee’s letter is not found in the Dialogue correspondence, Rees’s response is. To Lee’s hope that BYU Studies could fill the role of Dialogue, Rees wrote: “The greatly increased amount of scholarly writing on the Mormons demands more space than one journal can possibly provide.” Besides, an outlet like Dialogue filled a need as Rees explained further:

It is also true that Dialogue has some functions and purposes that differ from those of BYU Studies. By the very fact that it is associated with an institution, BYU Studies. . .has certain commitments which preclude its publication of materials on certain issues. It is good to have a publication like BYU Studies, especially of the quality it has attained in the past year or so. But it is also good to have a journal like Dialogue, which allows for an open discussion of many issues and events, even some of which are controversial. It is our belief that we have a great deal to gain by honestly and reasonably examining our faith, our history, and our culture, and by entering into dialogue with members of our own faith as well as those outside it.[172]

Rees concluded by asking Lee “to submit any writing to Dialogue that you think appropriate.” With such a diverse readership, some readers “are struggling with their faith and salvation and could benefit from your witness, counsel and testimony.”[173] Not surprisingly, Lee, who became president of the LDS church just two months later, failed to take advantage of Rees’s offer.[174]

At the encouragement of several BYU faculty, Rees also tried to interview BYU president Dallin Oaks.[175] This, however, was also unsuccessful. Three years later, Oaks denied a request Rees made to publish a chapter of a forthcoming book that Oaks was writing with BYU professor Marvin S. Hill.[176] Learning through Hill of Oaks’s refusal, Rees re ported: “Tonight [Hill] said that Dallin felt that some of the Brethren were uneasy about Dialogue and are watching it closely and if he were to publish in it, he thought it would hurt Dialogue and also hurt him. I fail to see how it could hurt either one of us, but I confess that my view of the world differs from that of 40 miles south of SLC [Salt Lake City].”[177]

Other interviews were granted, however. In addition to the afore mentioned Henry Eyring interview, Rees also included enlightening con versations with Mormon columnist Jack Anderson (interviewed by David King, Mary Bradford, and Larry Bush), and historian Juanita Brooks (interviewed by Davis Bitton and Maureen Ursenbach).[178]

Despite failing at some attempts to bring greater balance to the jour nal, Rees and his team proved that they could diversify its content and direction in a satisfactory way. For instance, several theme issues, in addition to those discussed earlier, defined much of the Rees tenure. Out of eighteen issues released under the Los Angeles team (counting each double issue as two), twelve had specific themes (and five of those were guest-edited). Rees writes: “I thought the idea of a true dialogue called for various points of view or discussion on the same topic—and I wanted to explore some subjects in depth.”[179] Other theme issues included one on Mormons and literature (Autumn/Winter 1971), Mormonism and American culture (Summer 1973), and Mormons and the Watergate scan dal (Summer 1974). Rees’s final two issues, one each on music and sex, are discussed below.

Rees also inaugurated a new column of personal essays under his editorship. Calling it “Personal Voices,” he saw this as an important contribution to the journal: “I have always felt that the personal essay was one of the most significant ways of communicating.”[180] He also increased the presence of poetry: “I felt that there were few (if any at the time) outlets for really good poetry and since I believe that poetry is important in a culture, I wanted to publish an ample amount of good poetry.” However, “it has a limited audience and some people complained that there was too much.”[181] Also, Dialogue veteran Ralph Hansen of the Stanford University library continued his “Among the Mormons” column, surveying current Mormon literature in nearly every issue.

Rees also made changes in the graphic image of Dialogue. For example, graphic artists David Willardson, John Cassado, and Gary Collins designed covers for special theme issues and tried to make them more relevant to the content generally.[182] They also used original and more contemporary type fonts for article titles. In addition to guest artists, the designers secured archival photography from such studios as Mangum and Bettman, both in New York (Spring 1972).[183] Simply put, remembers Rees: “I was trying to make the journal as interesting graphically as it was substantively.”[184]

Selecting a Replacement

By early 1975, Rees decided it was time for him to begin looking for a new editor to take over Dialogue. He had struggled with a turnover among his staff, having lost Brent Rushforth. Then in 1974, Gordon Thomasson and Frederick Williams, two valued associate editors, both left Los Angeles. Thomasson, who began work on his Ph.D. at Cornell, retained his title as an associate editor, but was able to do little from his new home in New York.[185] Consequently, Rees was left to carry out the most crucial editorial duties alone, unable to delegate them to the staff that remained.[186] He could only stretch himself so thin: “I find a vast majority of my time is spent in taking care of the day-to-day affairs of Dialogue. There are many manuscripts that need attention and I have not been able to find sufficient time to process them.”[187] So Rees began looking eastward to Mary Bradford in Arlington, Virginia, whom he saw as the person most qualified to take over the editorship. He approached her by telephone shortly before the summer of 1975 and, after a few months of deliberation, she accepted. Rees was grateful: “Five years. . .have taken their toll and I think it’s time for someone else to have a chance at it.”[188] Rees was immediately optimistic about Bradford, as he told Leonard Arrington: “I feel confident that in Mary’s hands Dialogue will take new and exciting directions.”[189] Over two decades later, Rees reflects back on his decision to step down: “I was ready to give it up, al though in some ways it was hard because [Dialogue] had been such an integral part of my life for so many years.”[190]

Wrapping Things up in Los Angeles

With only a few months left, Rees had much work to do and little time to do it. Already busy at UCLA, he would soon be appointed the director of the Department of Humanities and Communications in the extension division.[191] Short-handed in trying to fulfill his Dialogue duties, Rees immediately took advantage of Bradford’s acceptance and proposed several joint projects as part of the transition. Four issues would remain under Rees’s editorship, including two guest-edited theme issues, one on music and one on sexuality. Bradford and her team would oversee the sex issue (originally planned as a double issue). Rees envisioned that the two teams, working at opposite ends of the country, could put Dialogue back on schedule. Bradford would then officially take over on 1 April 1976 (later changed to May, then June).[192]