Articles/Essays – Volume 04, No. 3

A Letter from Israel Whiton, 1851

A crest of wind runs and rustles through the pinons

Below the butte, and it is evening; the moss-green shade

Glimmers with lancets and gems of the afternoon sun;

The fields beyond glow yellow-gold; and the overcast

Of azure dims pale and like powder in the air

Fails away into the recesses of light and time.

I sit before a candle that tips its flame

From the door, and I write . . .

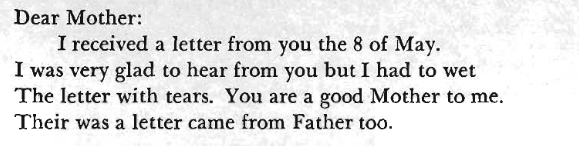

Dear Mother:

I received a letter from you the 8 of May.

I was very glad to hear from you but I had to wet

The letter with tears. You are a good Mother to me.

Their was a letter came from Father too.

I crease them at the edge of the desk, splinters

Shifting the pages awry . . .

I and Eliza have not forgot what you told us

Before we started our journey, If we was faithful

In the Gospel of the Priesthood, we should be instrumental

In the hands of God, of turning the hearts of the Children

To the Fathers. My health has been good every day

Since I left home; I am tough and herty, enjoying

Good health and this I am thankful for as usal.

There in New Haven, the bank of pillows and the skin

Like the river sand beyond the sheeting water

That subtly rises and fails, drawing grains

In the tumult of recession, and the eyes sudden

To see me near, from sleep, and my going away

Beyond the doors that she sees closing.

Eliza kept all my clothes in good order,

She was a good woman to take care of things.

I do not know what I should have done to travel

Without her; we had a team of our own, one yoke

Of oxen and 2 yoke of cows.

Over the plains from Laramie, west, the bow of mountains

Far to the south, and I write as if there, receding

Into the blue and golden undulations of distance,

Away from home and farther still to the great Divide

Of the land, and down the reaches of the far slope,

The canyons appearing between the walls and towers

Of rock and the high vales of the wind and the wisps

Of cirri against the high flanges of stone . . .

We took in Sister Snow and her little boy

To carry through to the vally for 75 dollars,

When we got about 3Q0 miles she died

With the Cholery. Her husband was to the gold

Minds and was a coming to meet her to the vally

In the fall, but I heard from him; he has been sick

In the Sutters’ gold minds and has not come yet.

By having Sister Snows things in my wagon

I had to by another yoke of oxen when I got

To Fort Carny where I got my cattle, because

She was foot sore and could not go, for 55 dollars.

The oxen before me, I watch the rhythm of the wagons

Tipping and heaving, and the finite dust

Settles in our wake, paling the sage on either

Side, and after. I am the measure of that journey,

Never to return, and here where the soundless sky

Drifts from the still clouds, and where it goes

I see the quiet periods of stars and the sleek

Heaven of that other certainty . . .

It was very bad for Eliza to have sickness

And death in her wagon on such a journey.

We see thousands and thousands of bufalows

Moving in great heards; we kill some and had

All the meat we wanted and it was as good

As dried beef. We kill some antaloope, in animal

As big as sheep; they was as good as mutton.

Manly Barrows kill a good many rabits because

He had a shot gun; I shot some sage hens

With Manly’s gun. We see some raddle snake;

A young man got bite by one, but got well,

Very early one morning there was one run under

Our wagon and they kill it. We see Indians

In droves without number; one rode up to my wagon

And give my Eliza some blake Cherrys

And she gave him two crackers. They all ride

Horses and have long slim poles fastened

To there horses to carry there game.

From the plain I see the declivity to the stream

Then as we brake the wagon with poles, to the water’s edge,

Then easily into the cold, the oxen threshing for footing

On the stony bed; I steady the wagon, reaching

From my horse to the buckboard, but over it goes

Like a vane against the current and the rills

Of cold, and Eliza sinks there before I catch her,

Her skirts the mantles of darkness, laden with water.

And she gazes wildly at me when I right her

And help her to the bank. She shivers as I right

The wagon from my saddle, and in the evening

I touch the question in her, of the exposure and cold

Of September, and the wind. She shivers again, trying

Against the cold . . .

We got to the Vally about the middle of October.

I work one yoke of my cattle, the old brindle some.

A cold storm come and one died. We have

Some brown sugar that we brought from St. Louis.

Wheat is worth 3 dollars a bushel, beef 10 dollars

A hundred and maybe potatoes 1 dollar a bushel.

There is grist mills and saw mills in the Valley a plenty.

The wheat on the ground bids fair for a good crop;

They raise from 40 to 60 bushels to acre;

After harvest they plow in the old stuble

And next summer get a great crop of wheat

Without sowing and this they can follow up

Year after year.

Eliza, you lie there, under the window, the last sunlight

Over your hands, and I cannot see where you

Must see, the pinons flickering like lashes

Over your eyes, the fire of embers waiting in the ash

White powdering over them . . . You lie there,

Tucked in the quilt you made for us in New Haven,

Still as the evening before the crest of wind . . .

Mr. Hunter finds teem and seeds and tools and land

And I have one half of the crop and give him

The other half in the shock. I have 18 acres of wheat

On the ground, Mother, it looks fine up to my knees.

We have good meetings every Sunday. Eliza is . . .

The Vally is 100 miles long and about 20 wide

With the river running through the middle, called

The River Jordan and Mountains all around

The Vally higher than the clouds.

But Eliza is still as I write, and I must only

Listen. I, Israel Whiton of the Salt Lake Valley,

Write this letter to you, Mother, from the canyons

And the butte above my land; it is a leaf

From the spring before we came, as both you and Eliza

Know, unanswerable except in the signs that come,

That I cannot seek. So I give it to the wind

From the tips of pinons or the butte, and it lifts

Away, and I try to see it as it diminishes

Away, then vanishing though I know it is there,

As you know better than I, Mother . . . And it will rise

Beyond the golden seal and touch the white hand

In the cirri pluming the Oquirrh crest west

Over the sunset, and it is as if I take a veil

Full in my hand as I write, as if to let it yield

To the days consecrated to the journey west

That holds me aloof from all I have ever known,

The East and the cities of my common being,

As I am here, in Zion, wondering about you

Who cannot respond except in the barest hints

Of being that lift over me and show me the way

To yield and rise into the Kingdom, the sky

And the land like the white silver spirit

That we know but is fathomless before us

And indefinite as the planes of God rising

Into the sun . . .

With love,

Your son Israel

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue