Articles/Essays – Volume 23, No. 3

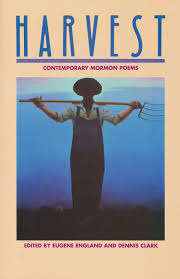

A Lot to Like | Eugene England and Dennis Clark, eds., Harvest: Contemporary Mormon Poems

Harvest is a good title for this collection of twentieth-century Mormon poetry with its bounty, variety, and degrees of ripeness and appeal. One feels a generosity of spirit emanating from this aggregate, a poetic vision that embraces the mother culture without militancy and looks outward as often as inward.

Most of the poems were originally published in LDS periodicals, but a number of the poets have published in journals such as the Southern Review, Poetry North west, the California Quarterly, Shenandoah, the Kansas Quarterly, and the Yale Review. These, then, are poets whom “Mormon” identifies but does not necessarily circumscribe.

The poems are, of course, the meat of an anthology, but here the editors have skimped on seasonings and side dishes. They arranged the poets in birth order (from 1901 to 1965), a common organizational device, and divided the collection into those born before 1940 or after 1939, with England selecting the earlier group and Clark the later. No birth years are provided in the exceedingly brief accounts of each poet at the end of the volume, and no outward sign indicates where England’s task ended and Clark’s began. This is not a trivial matter. It is of more than passing interest whether a poet came to adulthood in the generation of Hart Crane (b. 1899), Robert Lowell (b. 1917), or Sylvia Plath (b. 1932) and before, during, or after which of the century’s major wars or social movements, even though few of the poems address the topics of war, civil rights, or the women’s movement.

I wish the editors had written brief essays on each poet in the manner of Louis Untermeyer (Modern American Poetry, various editions). For a collection that is a landmark of sorts, the extra effort would have been worthwhile. The editors’ comments in lieu of an introduction are sketchy, too. England does the better job of providing a context for the poems, but I wish his essay was longer. Clark’s comments present his theory of poetry but do little to acquaint the reader with the diverse group of “younger” poets.

One might question the inclusion of hymn verses, despite their link to earlier LDS hymn writing. Nevertheless, the sweet simplicity of Bruce Jorgensen’s “For Bread and Breath of Life” (p. 260) appeals to me. I also wonder at the inclusion of John Davies, Brewster Ghiselin, Leslie Norris, William Stafford, and May Swenson as “Friends and Relations.” The editors say that these “first-rate poets” provide “standards for comparison” (p. vii), and indeed they do. Still, their presence shows a little uncertainty that these fine Mormon poets can carry an anthology on their own. They can.

Many of the poets are multi-degreed and earn their livelihoods in academia. Nevertheless, their poems are very accessible. Few display deliberate obscurantism, poetic posturing, or neurotic narcissism. Though accessible, the poems are not necessarily undemanding of the reader. The ten-line “Tag, I.D.” by John Sterling Harris (p. 49), for example, despite its simplicity, resonates volumes beyond its thirty-eight words.

Some of the poets succumb to the understandable temptation to write about ancestors, with mixed results. Susan Howe’s “To my Great-great Grandmother, Written on a Flight to Salt Lake City” (p. 194) seems forced and the plains-crossing ancestor shadowy at best, while her “The Woman Whose Brooch I Stole” (p. 196) provides concrete detail that gives the poem authenticity. Loretta Randall Sharp’s “October 9, 1846” (p. 103), recall ing the “miracle of the quail,” almost succeeds. The fourth stanza is splendid:

A sudden whir, a throaty trill, the swell

of speckled wings: and the dry beds filled

with food. The quail came, strutting

the camp, tracks faint as scattered chaff.

The pear-shaped birds did not flatten

shy and wild in the grass. Crested heads

pivoted from child to child who picked

them, eyes wide at the bloodbeat of such

feathered fruit.

In the next and final stanza, though, she abandons deft imagery and music to tell readers in prosaic language that a mir acle has occurred:

No gun was needed to feed these six hundred

destitute. Six times the birds circled

the camp, six times landed. At each rising

the flock increased, and at the seventh

swell, the mottled augury took leave

that saints might praises sing

while making way to the Great Salt Lake.

A strong narrative voice runs through the collection. Iris Parker Corry tells a pioneer heroine’s story (pp. 26-27) so directly and without sentimentality that poem and subject become one. The stark opening stanza is almost a capsule his tory of the handcart disaster:

Nellie Unthank

aged ten,

walked, starved, froze

with the Martin Company

and left her parents in shallow graves

near the Sweetwater.

Clinton F. Larson’s “Jesse” (pp. 30-31) and “Homestead in Idaho” (pp. 33-38) recount other tragedies. David L. Wright’s “The Conscience of the Village” (pp. 51-60) tells of an aging Brother Daniels who saw God and Joseph Smith “one rainy night.” Another narrative, “Millie’s Mother’s Red Dress” (pp. 135-37) by Carol Lynn Pearson, manipulates the reader, but I let it carry me along anyway because we all know Millie’s self-sacrificing mother. Compare this poem with May Swenson’s “That the Soul May Wax Plump” (p. 280), which shows a master at work on a similar theme.

As one might expect, the lyric voice is also very strong. I like “Fishers” by Robert Rees (pp. 96-99), which captures precious moments between father and son, although the poet comes close to losing his terrific “catch” to sentimentality at the end and may have lost it for some readers. In “Somewhere near Palmyra” (p. 100), Rees effectively uses concrete imagery to lead readers toward an understanding of the Prophet Joseph (11. 10-21):

personages of fire,

jasper and carnelian,

dispersing the morning dew;

images that bore him

through dark of night

terror of loneliness,

blood of betrayal,

the ache of small graves,

to death from the prison window

where, wings collapsing

through the summer air,

he fell—

“Gilead” (pp. 101-2), also by Rees, is far less successful and near its close offers two lines —”and at once all the trees of the field / clap their hands and rejoice”—that unhappily recall the muse of Joyce Kilmer.

Kathy Evans’s “Handwritten Psalm” (p. 171), as delicate as a lyric can be, shows the power of a light, understated touch. Entirely different, “Psalm for a Saturday Night” (p. 94) by Eloise Bell sings like a psalm of David and on one level ironically mirrors the biblical psalmist’s self-absorption. But that is just one facet of this well-crafted gem.

Laura Hamblin’s “Divorce” (p. 229) has an elliptical feel that is almost oriental. And Richard Tice demonstrates his mastery of the often-abused haiku form (p. 213). This one is exceptional:

night rain

against the water, young rice

into the rain

Lance Larsen writes with clarity, vigor, and control and is a keen observer of the telling detail. “Passing the Sacrament at Eastgate Nursing Home” (p. 237) is an outstanding poem on a religious subject. I also like his “Light” (p. 233) and “Dreaming Among Hydrangeas” (p. 235).

Other poems I found especially pleasing include Veneta Nielsen’s “Nursery Rhyme” (p. 6), Donnell Hunter’s “Children of Owl” (p. 69), Vernice Pere’s “Heritage” (p. 115), R. A. Christmas’s “Self-portrait as Brigham Young” (p. 132), Dixie Partridge’s “Learning to Quilt” (p. 150), Clifton Jolley’s “Prophet” (p. 167), Mary Blanchard’s “Bereft” (p. 198), M. D. Palmer’s “Rural Torillas” (pp. 204-5), Timothy Liu’s “Paper Flowers” (p. 248), and many more.

Other readers are sure to find a lot of poems to like in Harvest. Moreover, the best poems in this collection compare favorably with those of the “first-rate poets” included by the editors. This is an important literary work, a landmark that suggests greater things are yet to come.

Harvest: Contemporary Mormon Poems edited by Eugene England and Dennis Clark (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 328 pp., $14.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue