Articles/Essays – Volume 25, No. 3

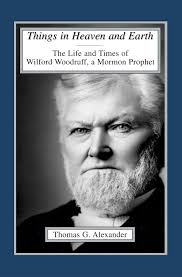

A Modern Prophet and His Times | Thomas G. Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff, a Mormon Prophet

Thomas G. Alexander, professor of history at Brigham Young University and prominent scholar of Mormon studies, has completed his long-awaited biography of Wilford Woodruff. An important nineteenth-century Mormon leader, Woodruff served as fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1889 until his death in 1898 at age ninety one.

In leadership style and personality, Woodruff contrasted sharply with his three predecessors. According to Alexander, Woodruff lacked “the creative brilliance of Joseph Smith, [shied away] from the public confrontation and ridicule used at times by Brigham Young, and [eschewed] the stern and uncompromising public pronouncements of John Taylor; Woodruff [by contrast] more frequently sought private compromise and conciliation” (p. 304). Woodruff was, Alexander asserts, “arguably the third most important figure in all of LDS church history after Joseph Smith . . . and Brigham Young” (p. 331).

Alexander effectively presents Wood ruff as a devout follower of a nineteenth century Mormon religion which promoted “a world view that unified the temporal and spiritual realms in God’s kingdom and in the lives of church members” (p. xiii). Indeed, the central theme of Alexander’s biography is Woodruff asserting a “holistic conception of the temporal and spiritual arena” within a world which he believed on the brink of imminent apocalypse—or mass destruction of all wicked peoples (that is, non-Mormons).

Woodruff anxiously promoted the cause of Mormon millennialism as he rose through the ranks, becoming a member of the Quorum of the Twelve by 1838 and president of that body in 1880. Relent less in his missionary efforts to gather the faithful to Mormonism’s Zion to build “a new heaven and new earth,” Woodruff sought to prepare for what he saw to be the imminent millennium and Second Coming. He fervently believed that he and his fellow Latter-day Saints were literally living in “the latter-days.”

However, by the time Woodruff became Church president in 1889, Mormon millennialistic expectations were in decline. The new president, along with other Church leaders, desired a more peaceful relationship with the secular, non-Mormon world, seeking cooperation rather than confrontation in political and economic arenas. Underscoring this changing position, the Church under Woodruffs leadership moved to abandon its controversial practice of plural marriage by issuing the so-called “Woodruff Manifesto of 1890.” By these actions, Woodruff, according to Alexander, “turned a psychic corner, completing a process begun some years before of dividing the previous holistic kingdom and separating the temporal and spiritual” (p. xiv).

Alexander’s account of the life and times of Wilford Woodruff utilizes abundant information from Woodruffs own voluminous journals—a rich primary source dating from the mid-1830s to the late 1890s. Here Woodruff carefully chronicled his activities and impressions of what was happening around him. In addition to the journals, Alexander has effectively utilized throughout his narrative the most recent scholarship in Mormon history, American religious studies, and social history. With some admiration, Alexander presents Wilford Woodruff as a multifaceted man who, with general success, balanced his role as Church leader, businessman, civic leader, and scholar with his primary responsibility as the head of a large polygamous family of nine wives and thirty-three children.

Alexander’s portrait of Woodruff is balanced and even-handed. This is no hagiography, as biographies of prominent Latter-day Saints are sometimes prone to be. Woodruff is presented here as a devout Latter-day Saint whose “sense of personal piety [was] unsurpassed by any nineteenth-century Mormon leader” (p. 332). Yet Alexander also discusses his faults and shortcomings. Though Woodruff was aware of “the necessity of compromise and discussion in achieving aims,” Alexander notes that the Mormon leader was “critical—perhaps even intolerant—of those who refused to enter into such dialogues” (p. 332).

Woodruff was also so “conservative and orthodox in his views” that “he had no sympathy for friends” who wanted the church to move “more rapidly toward a pluralistic society than [he] . . . thought advisable” (p. 331). His complex family life is forthrightly presented as less than idyllic. Alexander notes that “he did not treat his wives and children equally” (p. 332). Four of his nine wives left him, little of Joseph Smith, Jr.’s or the emerging church’s administrative personality. Length and format limitations in a work like this unfortunately necessitate generalizations which prove much too limiting for the expansive mind of Maurice Draper.

Nevertheless, Draper does draw the readers’ attention to many significant administrative situations. In many cases, these reflect problems and concerns that he himself faced as a member of two leading quorums of the RLDS Church: the Twelve from 1947 to 1958 and the First Presidency from 1958 to 1978. As a result, the book reveals much about RLDS administrative personality, and nearly as much about Maurice Draper as about Joseph Smith, Jr.

Draper initiates an insightful exploration of the impact of experience and circumstance upon Joseph’s administrative style. His discussion of individual agency versus authoritative leadership (pp. 168-69), illustrated by his reference to the First Presidency and High Council’s general letter to the “Saints scattered abroad,” is especially useful. Yet I still wanted to know more about the evolution of church administration: the struggle over corporate structure and procedure; the role of government; the church’s search for and pursuit of authority; priesthood structure; and stewardship procedure, gathering, and temple building, to name a few examples.

It is my hope that Maurice might expand upon this foundation, for his valuable insights would ably serve the scholarly community.

I also look forward to future, perhaps less reserved, commentaries on the ad ministrative actions of the founder of the Restoration. Nevertheless, employing this approach, The Founding Prophet provides instructive illustrations of the movement’s early organizational and doctrinal development.

Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff, a Mormon Prophet by Thomas G. Alexander (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1991), 484 pp., $28.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue