Articles/Essays – Volume 04, No. 1

A Mormon Play in Broadway | Don C. Liljenquist, Woman Is My Idea—A Comedy

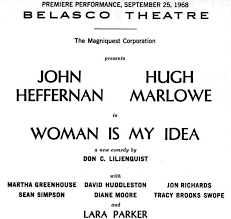

Woman Is My Idea, a comedy by Don C. Liljenquist, was produced and directed by Don C. Liljenquist at the Belasco Theatre in New York on 111 West 44th Street on Wednesday, September 25, 1968. The critics and reviewers of the play were unanimous in condemning it. The play closed after four or five performances. The last two sentences are a familiar summary of at least seventy-five percent of the plays that open on Broadway. The only difference to be recorded here is that this is a play about Mormons, written and directed by a Mormon. Not too long ago such an event might have created much comment in the press and even a discussion of Mormon principles. Be it said for the reviewers that not one of them made any derogatory reference to Mormonism. One critic even said defensively that the play “makes Mor mons morons, which they are not.” Since Mormon culture does not produce many playwrights and rarely one who seeks a Broadway production for his writing, an evaluation of this play seems in order. It can readily be said that as a producer, Liljenquist chose too tough an assignment in presenting an unknown director and playwright and a cast relatively unknown to Broad way. Yet most critics praised Liljenquist’s direction and had commendation for his cast. The crux of the failure was the plot of the play and its writing. Liljenquist insists that his play is simply about a confirmed bachelor who is pressured into marriage. Unfortunately, this plot is almost as overworked and hackneyed in the theatre as is doggerel verse on a Mother’s Day greeting card. A fresh point of view, perception, humor, and satire must be used to bring success to such a plot.

The author of Woman Is My Idea has tried for some uniqueness by placing the situation in the Mormon community of 1870, at the high point of the polygamy crisis. The author declines, however, to explore this material to any depth. There is, to be sure, an authentic setting, the home of John R. Park; there are Mormon jokes about polygamy and an offstage crowd singing Mormon hymns. Brigham Young appears in the play, his main function being to perform Park’s two marriage ceremonies. Park, the founder of the University of Deseret, is characterized only through the whimsical story of his marriage. He surrenders to church and community pressures and marries a young woman “for eternity” supposedly on her deathbed. Immediately after his marriage Park arranges to pay his wife’s funeral expenses and departs for a five-month trip to the East. Expectedly to the audience, if not to him, Park returns to find his wife completely recovered. She greets him in a wedding dress made by the Relief Society and shows him his redecorated house and the double bed in his bedroom. The young bride, aided by her two irrepressible sisters, convinces Park that he should not only resign himself to being a happy husband for her, but might do well to marry the other two. Although the historical facts of the polygamy crisis are forthrightly stated, they are used only as background. Even though Brigham Young is jailed by order of the Gentile judge (one of Park’s boarders) who in turn runs away in fear of both Young’s predictions and his Danites, these factors have little effect upon the plot other than to make the tone more serious and the pace slower than re quired for light comedy. The religious and church elements used in the play are stated without debate. The author is not up to the large order of making eternal marriage comic material. He has his character Park dispose of it with the statement that God can take care of eternity. The total effect of the use of the religious, historical, and comic in this play is inoffensive and even whole some, but the play is not buoyant enough (despite some moments of charm) to keep an audience entertained for two hours; neither is it strong or virile enough to support its historical characters. The opening night audience, composed largely of well-wishers and Mormons, was jittery and over-anxious, while the critics were obviously bored.

Surely, the characters of the play should illustrate the desirability of marriage or the joys of bachelorhood. Neither is developed to any extent and the amusing lines and situations are far too infrequent. A comic polygamous character calculating that the number of his posterity in two generations will be roughly a million people adds zest to the play, whereas his female counterpart, the neighbor housekeeper, insisting incessantly on Park’s marriage, is maddeningly tedious. (The audience must have thought she had forgotten all her lines except the one she repeats.) The character of the federal judge played for comedy seemed almost a villain out of a melodrama. The actors carrying the major plot action tried to bring warmth and buoyancy to their characters in a play that permitted little depth or ebullience; their portrayals as a result were uneven and frequently static. John Heffernon’s John Park was convincing and personable, although the philosopher-president was not much in evidence. Hugh Marlowe as Brigham Young brings support, dignity, and strength to a character which has little bearing on the plot. David Huddleston and Richards add comedy to the play. The bride, Lara Parsons, is gracious and charming, and her two sisters bright and spirited. The young nephew piques curiosity and seemingly has a real conflict: his love for the bride versus his loyalty and devotion to Park, but little is made of this conflict which might have resulted in a more interesting play or at least a more unpredictable one.

Perhaps the problems that confronted Liljenquist will plague any Mormon playwright trying to write in a comic vein on a Mormon theme. Is it possible to make religious history comic? Perhaps we will have to wait for a Mormon Sholem Aleichem before we can have a Mormon “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue