Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 1

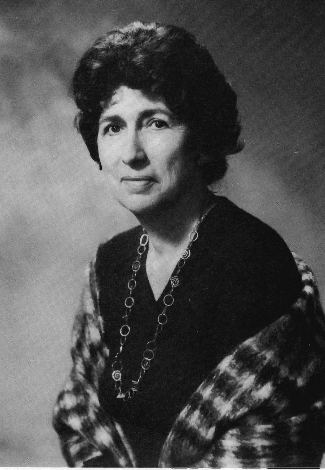

A New Climate of Liberation: A Tribute to Fawn McKay Brodie, 1915-1981

I am honored by the invitation to write a tribute to Fawn McKay Brodie. Professor Brodie was no doubt the most widely known and read of all Mormon writers, a historian of distinction whose work over a period of thirty five years has attracted international attention and very considerable acclaim. Her early interests and university studies and degrees were in literature, and as a writer she turned her exceptional literary talents and energy to biography, producing, among other works, widely read biographies of Joseph Smith, Sir Richard Burton, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Jefferson, and a yet to-be-published work on Richard Nixon. The Nixon work was completed just before her death.

On the history faculty at the University of California at Los Angeles, Professor Brodie’s teaching was directed especially to historical biography. As a biographer she was greatly influenced by the school of the German philosopher and historian of ideas Wilhelm Dilthey and by the psychology of the Freudians, influences which have been central in the development of contemporary psychohistory, where it is held that historical explanation is achieved through Verstehen. This is the method of empathetic understanding where the historian attempts to achieve an imaginary identification with the subject of the historical events and thereby understand them through an intimate grasp of the circumstances, interests, and motives which produced them. In commenting on her methods as a researcher and writer in a 1975 interview, Professor Brodie disclaimed any experience and competence as a clinician in psychological or psychoanalytical matters, but strongly defended the methodology of psychohistory in historical research and writing.[1] She identified herself, however, as more psychobiographer than psychohistorian, a qualification that seems entirely appropriate considering the concentration of her work.

It is this strong bent toward psychobiography as compared to the traditional, more external or even positivistic treatment of biography, of course, that enlivened the materials with which Professor Brodie worked and at the same time occasioned much of the more competent criticism which her books generated. This can be seen in some of the critical reactions to her volumes on Jefferson and Joseph Smith. Her method of treating her subjects enabled her at times to exploit the controversial facets of their character and behavior, all of which made interesting reading and ran the risk of serious error. In the 1975 interview Professor Brodie herself warned against the “dangers” latent in the method of psychobiography. It is surprising that while she made it clear that this was the method employed in all her other biographies, she said that in her work on Joseph Smith, No Man Knows My History, she was not involved with it “except by inadvertence.”

It was the Joseph Smith volume, of course, her first biography, that made Professor Brodie famous among Mormons and students of Mormonism be fore she was well known in academic circles. When this book hit the Church in 1945, it produced more intellectual excitement than the Mormons had known in decades. The Mormons were accustomed to every variety of criti cism, and both the Church and the people had learned to take it in their stride. But here was a prize-winning book from a leading publisher, meticulously researched and well documented, with every appearance of reliable scholarship, written by a young woman from one of the foremost families of the Church who had been reared in a conservative Mormon village and schooled through college in Utah, and yet a book which seemed to undercut the very foundations of Mormonism. It was a fascinating work that at tempted to penetrate the mind and motives of Joseph Smith and explain his behavior and the moving events in the early life of the Church in entirely naturalistic terms. It described the prophet, a remarkably complex person and in the esteem of many Mormons an almost deified one, as an all-too human human being. It demythologized the beginnings and early history of the Church to the point of denying its divinity. It was a book that could not be ignored.

The Church excommunicated Mrs. Brodie, and some of its leading scholars ridiculed her book. Some Mormons and many non-Mormon historians hailed it as the first competent work on Joseph Smith, even a definitive work, and as the first objective study of the beginnings of Mormonism, subjects which for decades had been plagued by prejudiced writers for and against. The most competent analysts of the Brodie book found much to praise as well as much to criticize. But their praise far outweighed their criticism. Vardis Fisher, the author of the great novel Children of God, criticized her handling of some of her sources and her account of the “metamorphosis” of Joseph Smith, saying that her book is “almost more a novel than a biography.”[2] Dale L. Morgan called the book a “definitive biography,” “the finest job of schol arship yet done in Mormon history.”[3]

Whatever its merits and demerits, the Brodie book was a watershed in the treatment of Mormon history by Mormon historians. I believe that because of No Man Knows My History, Mormon history produced by Mormon scholars has moved toward more openness, objectivity, and honesty. For the past half century Mormon religious thought has been in decline, but since the forties the Mormon treatment of Church history has greatly improved—not simply because of a breakthrough in the Church’s proprietorship over its own history and improved access to the historical materials, or because of increased Mormon competence in historiography, but rather because among the historians there has been more honesty, a more genuine commitment to the pursuit of truth, and greater courage in facing criticism or even condemnation. Numerous factors determine such things, but quite surely in this case the honesty and courage of Mrs. Brodie have been among the most important.

No historian can even hope to construct a full and accurate picture and entirely adequate interpretation of a complex historical subject. There are too many problems associated with the selection and verification of data, the identification of causal relations, principles of analysis and interpretation and the historian’s own disposition and presuppositions. In Professor Brodie’s own words, “Even the most dispassionate historian, trying to select fairly with intelligence and discretion, manipulates in spite of himself, by nuances, by repudiation, by omission, by unconscious affection or hostility.”[4] Genuinely competent historians must and do expect criticism. They should welcome it, as it is essential to their search for the truth about what happened and why it happened. But competent criticism is one thing, defamation is something else. For her work on Joseph Smith, Fawn Brodie received not only high praise and competent criticism, she was all too frequently the object of vilification—and that by many who knew little or nothing about Joseph Smith or Mormon history beyond what they had gleaned from the Church’s own propagandistic literature or from those Mormon writers who are simply apologists for the Church and their religion.

I am personally not partial to psychohistory; it is interesting and can be exciting reading, but as Professor Brodie herself has said, it is fraught with danger. In the foreword of her biography of Jefferson, she wrote, “Though this volume is ‘an intimate history’ of Thomas Jefferson, it attempts to por tray not only his intimate but also his inner life, which is not the same thing. The idea that a man’s inner life affects every aspect of his intellectual life and also his decision-making should need no defense today. To illuminate this relationship, however, requires certain biographical techniques that make some historians uncomfortable. One must look for feeling as well as fact, for nuance and metaphor as well as idea and action.” Although she disclaimed intentional involvement in psychobiography in her study of Joseph Smith, I believe this statement would have been appropriate for that volume as well. In the foreword of the second edition Mrs. Brodie referred to her “speculations” regarding the character of Joseph Smith. The book should be read with that reference in mind. A part of the trouble is that most devout Mormons do not want the “intimate” life of their prophet investigated and publicized and they are not comfortable with efforts to examine his “inner” life. Except for the Reorganites, they were pleased, of course, that Brodie made a solid case for the prophet’s polygamy, though many were more than a little disturbed by her report that he may have had almost fifty wives. But they found quite distasteful her disclosure that a man who goes in for marriage on such a heroic scale must occasionally leave his wife (wives) at home in the evening while he engages in a bit of courtship.

Gilbert Highet wrote of the Jefferson volume, “This is a sensitive, eloquent and far-sighted biography.” I regard No Man Knows My History as sensitive and eloquent. Of its author I can only say that she was both honest and courageous in her search for the facts on the origins of Mormonism and in her attempt to describe the Mormon prophet. In the 1970 preface to the second edition, she referred to the “new climate of liberation” in the Church, which she credited in part to the founders and editors of Dialogue, and wrote that “the fear of church punishment for legitimate dissent seems largely to have disappeared.” Whether this “new climate” augurs well for the future or is an apparition that is already fading, time will tell. But we can be sure that Fawn Brodie was one of its chief creators and those in the Church who value the authentic quest for truth owe her a great debt.

In 1967 the Utah Historical Society conferred on Mrs. Brodie its highest honor by making her a Fellow of the Society. Her acceptance speech, which she aptly described as a “two and one-half minute talk,” was a deeply moving experience both for her and her audience. It was something of a reuniting with her intimate society from which she had long been estranged. The occasion, she said, was “in a sense a tribute to the right to dissent about the past,” as indeed it was. Of the Utah Historical Society, she said that “It has had faith that the good sense and compassion of the reader would in the end sort out the malicious writing from the unmalicious, the bigoted from the unbigoted.”

[1] Fawn McKay Brodie, interviewed by Shirley E. Stephenson on November 30, 1975, in the Brodie Papers of the Marriott Library, University of Utah.

[2] Review in New York Times Book Reviews, November 25, 1945, p. 1.

[3] Saturday Review, November 24, 1945.

[4] “Can We Manipulate the Past?” First Annual American West Lecture, University of Utah, 1970.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue