Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 1

A Proselytor’s Dream

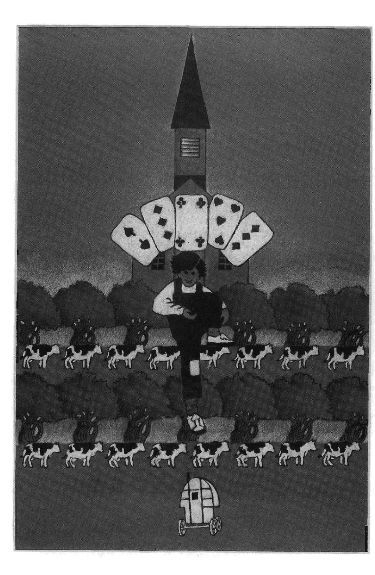

Mary Mahoney, a devout Catholic, left Kentucky and came west to Basalt, Idaho, where she met her future husband on the steps of the old LDS ward house. She was a Mormon for the remaining fifty-two years of her life, yet Grandma Mary never gave up the crucifix on her mantel, and one night the home teachers tried to sneak it into the fireplace.

I can’t think of my childhood without recalling the fine white ivory of that crucifix against my fingertips. Grandma’s occasional Latin mumblings always puzzled but intrigued me, and I wanted to learn everything about Catholics. When I was thirteen, she gave me weekly religious instruction, which I later recognized as a sort of catechism. She never did this with my sisters; somehow she had singled me out as the most vulnerable, perhaps the most like her.

As a young woman, she had delivered many babies, and once as we sat side by side awaiting the sacrament, she said, “A midwife’s trademark is bloody hands. They always reminded me of the stigmata.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Christ’s wounds from the crucifixion.” She patted my hand and whispered, “The holy eucharist is coming. Be quiet now, Molly.” Under her breath, she explained the transubstantiation of the sacrament bread and water into the actual body and blood of Jesus. “Only the taste and color remain behind,” she whispered, as I intoned “While of These Emblems” and glanced sideways to see if my mother had overheard this false doctrine.

Grandma’s warped theology influenced me more than I cared to admit, and whenever I dared speak up in Sunday School class, some freak mixture of Catholicism and Mormonism would drop inadvertently from my lips. I once found myself repeating monotone Latin chants in seminary class during a scripture chase.

I refused to wear a headscarf, ever, because it represented proper Mass attire. All my high school friends wore paisley triangles over their hair rollers as we drove up and down Main Street on Saturday afternoons. I was nicknamed “Nettie” because of my pink hair net.

While the other kids goofed around, I pored over the standard works and read every book I could find on Catholic doctrine. I was determined to know if my grandmother was right. Practically every day I presented my dad with a new question about religion. “The pest is here again,” he would always say good-naturedly, looking up from his desk. Even if he knew the answer, he would say, “Hand me my scriptures,” and together we would research the question. Once I asked him about Grandma’s unorthodoxy and he said, “She’s just getting senile. Don’t pay any attention when she talks like that.”

I majored in medieval history in college, writing my senior thesis on “Basic Doctrinal Changes in the Catholic Church During the Medieval Period.” Grandma read it with tight lips, later burning it in the fireplace, hoping it was the only copy. For two months she refused to sit next to me in church, and when I caught her caressing her rosary one afternoon, she slapped at the air, trying to banish me from her sight. After Grandpa died and she moved in with us, I was refused access to her bedroom, although I had been her favorite once.

When my World Religions class toured the Huntsville monastery, I scrutinized every brick and window pane, wondering about Grandma’s origins. Our institute teacher had suggested covering our heads, so I was wearing a frail silk scarf printed with pink and red roses. I thought about my pink net and wondered if it would be considered a suitable head covering in this sanctuary.

Before we left, I bought a box of caramels and a paperback copy of Facts of the Faith at the monks’ store, thinking all the while of Father Bernard, a monk in his late thirties with dark Italian eyes, who had briefly forsaken his vow of silence to explain the monastic system to us. While I studied his drab brown robe, I entertained thoughts of his leaving both the monastery and his church for me and Mormonism. An authentic proselytor’s dream.

As I ate the caramels, our Bluebird bus sped along the freeway past acres of alfalfa and cows, and I became less romantic and pictured Father Bernard repenting of his love for me and sneaking off to an out-of-the-way cathedral to confess he had suffered too much, had not lost his faith, and saw the futility of dispelling his Catholic loyalties. He would then marry an ex-nun, and I would go on with my search for the perfect Mormon husband.

As it turned out, I forgot Father Bernard within a week and focused my romantic attentions on a five-year string of inactive Mormons and non members. We always ended up arguing religion, I inevitably tried to convert them, and not one lasted more than three months.

“Why don’t you find a nice Mormon boy and settle down?” my mother kept asking. She thought I perversely turned down dates with anyone who could quote the Articles of Faith, but the truth was, nice Mormon boys never asked me out. One boy in my institute class advised me to stop acting so controversial, then added, “If you’d quit singing those Handel arias and try ‘Climb Every Mountain’ you’d be more popular.”

I taught school for five years and had a total of three dates with active LDS boys. Finally, at age twenty-six, I met Bill Weston at a fireside. He was a discus thrower gone to pot, his thick chest and biceps sagging, his sandy hair receding, even at twenty-eight. He shook my hand and said, “I really enjoyed your singing. Handel is one of my favorites.” Ten minutes later we were discussing Peruvian customs and Bill was telling me about all the Catholics he had converted.

Bill was an elder’s quorum president, no less, whose forebears on every side crossed the plains in handcart companies. I told him of my grandparents’ living in a dugout in the Idaho wilderness, with Grandma delivering babies and Grandpa digging irrigation ditches and pondering what the crops were like back home.

I mentioned Grandma Mary’s crucifix and her ideas on the sacrament. “I saw that in Peru so many times,” Bill said. “Some people never escape the teachings of their childhood. Even though they’re converted by the spirit, mentally it’s hard for them to make the change.”

I had the feeling he viewed our dating as a fellowshipping assignment. For months, we never went anywhere together except sacrament meeting, conference or firesides. “I’m just trying to educate you,” he laughed when I suggested we see a movie. “I don’t want to cuddle up next to you in a dark theatre until I’m sure you know enough about the gospel to teach it to our children.”

The next night we prayed together for the first time. I was embarrassed to kneel beside him in my mother’s living room, even though everyone else had gone to bed. I dreaded the idea of Grandma stumbling over us on her way to the bathroom, chanting her Latin benedictions. But afterward I felt very secure and calm as Bill put his arm around me and kissed me.

Our courtship progressed quickly. We “eloped” to the temple, not telling anyone but our immediate families, then spent our honeymoon in a room over his uncle’s Chevy showroom in Wendover, Nevada.

“I’m glad you’re not a gambler,” Bill laughed when I refused to play even a single slot machine. “I was worried you and your grandma might suggest Bingo in the cultural hall on Friday nights.”

Back home in Boise, where Bill was just starting his law practice, we had no friends and no family. Over the months we became friendly with our non-member neighbors. One night Marsha, who lived next door, invited us over to meet her priest. So Bill and I decided to socialize a bit and perhaps sneak in a few hints about Mormonism.

Father Timothy Ashcraft sat cross-legged on Marsha’s carpet, strumming his guitar. “So,” he said, showing dimples as he grinned knowingly at me, “does this Relief Society of yours give food stamps?”

I knew I was being mocked and smiled wanly, fingering the center part in my hair and longing for Bill to return from the kitchen with my orange juice and rescue me from this inquisition. As the priest continued his questions, he leaned closer so that I could smell the wine on his breath. His white collar was immaculate. I pictured it with a little gold stud at its center front, like the barbershop-quartetters wear. And sleeve garters. He rubbed his fingertips over the light stubble on his jaw, reminding me he was a modern, unshaven priest.

Bill finally wended his way through the people lounging on the carpet. He handed me my juice, then sat beside me on the floor, his arm around my waist.

“You have bishops and priests in the Mormon church, don’t you, Molly?” Father Ashcraft asked, turning to me again.

“You stole those words from the Catholics,” Marsha joked.

Bill mentioned the apostasy. “No one knew anything during the Middle Ages,” Marsha said loudly, and I thought of Grandma burning my thesis.

“The priesthood was withheld from the earth,” Bill went on.

“Speaking of priests,” Marsha said, “honestly, what do you think of our divine Father Ashcraft?” She removed the elastic band from her ponytail and let her bleached hair cascade over her shoulders like a sixteen-year-old’s.

“Father Tim,” the priest corrected. “And I have no claims to divinity.”

“Isn’t he a terrific guitarist?” Marsha asked, raising her thinly-plucked eyebrows. “Hey, he could accompany you, Molly. You could sing, ‘Ave, Maria’ at our next folk mass!” She brushed Father Ashcraft’s knee with her wrist, dangling a charm bracelet with several silver crosses against his pantleg.

I shook my head and a strand of hair clung to my lipstick. Bill nudged me and said, “Maybe you should, Molly.” He tucked the hair behind my ear while the priest said the mass would be held April twenty-first.

“Oh, goody,” said Marsha. “It’s settled.”

“I think this could be a good missionary opportunity,” Bill said, removing his cuff links as he slumped onto our couch at home. April twenty-first was Passover, according to his pocket calendar. We both laughed at this ecumenical movement—a Mormon singing at Passover mass.

I knew somehow that Grandma Mary would have approved of my upcoming performance, and the idea made me even more uncomfortable. “Honey, you can borrow my Perry Como Christmas album to get pointers on ‘Ave, Maria,'” Bill said, leaning back against a couch cushion.

“Thanks a lot,” I said. “I suppose you think it’s appropriate for me to go around chanting, ‘Hail, Mary’?” He just laughed.

I wished I could disguise myself somehow, wearing sunglasses or painting thick makeup all over my face. Myrtle Miller, my voice teacher, had always told me not to hide my eyes while singing. “Emote through your eyes,” she said. “If you wear glasses, take them off. And paint a red dot just at the juncture of your inner eyelids. It brings out the white of your eyes and lets the audience capture your fervor.” I suggested to Bill that he sit at the back of the church and search for my crimson spots and patches of fervor here and there.

St Augustine’s Cathedral was ablaze with hundreds of candles on that Passover evening. “Molly!” Father Ashcraft greeted me, swishing up the aisle in his black robes. He was very handsome, with hair as black as mine, and hazel-yellow eyes. He had shaved for this occasion, and the robes made him look austere, sacrificial. I was reminded of Father Bernard and I felt uncomfortable and shy in my hat of white feathers.

There was no prelude music. The organ was covered with dark green velvet, a three-pronged candelabra atop it. Father Tim seated me in the second pew, then disappeared through a door behind the altar.

There was a conspicuous hush in the church. Then from a distance came the strains of a single guitar, playing Bach. I wished Bill were with me, but his Seventies’ quorum meeting was making him later than expected.

Marsha slid in next to me and pressed my hand. She, too, was fellow shipping. I touched the ludicrous feather hat perched on my dark head like a beached seagull and wondered if, in Marsha’s opinion, I would make a likely candidate for conversion.

Father Ashcraft strolled up and down the aisles like a troubadour, guitar, strap of vivid yellow braid draped casually over his vestments. Then, standing at the altar, he intoned a few English phrases, his head bowed. The congregation murmured its reply. There was no Latin spoken here.

Marsha knelt on the velvet-padded board elevated six inches from the floor, her blond hair was caught at the nape with a tortoise-shell barrette. She wore no head covering. I thought of Grandma Mary’s reaction to bare headed women in church: blasphemy.

The hinges on the kneeling boards squeaked as they were pushed back into place. Father Tim looked up abruptly, singling me out with his eyes, and said, “Mrs. William Weston, a visitor with us, has consented to sing.” I stood and mounted the stairs, feeling silly and conspicuous in my ankle-length maternity dress and the seagull hat.

As the priest plucked out the staccato introduction on his guitar, I looked over the audience just in time to see Bill slip into a back pew and grin up at me, his teeth gleaming in twilight and candlelight. There were perhaps fifty people scattered about the fourteen double rows.

My stomach was churning and my ankles trembling. What did these people think of this newcomer, this alien, this Mormon, thrusting herself upon them and upon their sacred, although informal, mass?

I began my first “Ave” on F-sharp below middle C. At our rehearsal, Father Ashcraft was astonished to find I needed the usual key lowered so much. “A true contralto,” he pronounced, as though expecting me to kiss his ring.

I had practiced daily for three weeks, and my voice had regained the edge it had lost through months of inactivity. The melody seemed to lift me up, to transport me somewhere across the nave. I could tell it was audible, even on the pianissimo, to the last row. I was singing to each kerchiefed young woman in the congregation, thinking of my grandmother as a girl, attending mass daily, her head obediently covered.

There was one particular girl, two pews ahead of Bill, who with a cross around her neck, and her dark hair and eyes resembled Grandma Mary’s youthful pictures. What did my grandmother feel, I wondered, having been disowned by her family for marrying a pale Mormon boy with a faith as solid and unswerving as hers was torn and indecisive. Stuck in a dugout on the frozen Idaho prairie, longing for her folks in the lush bluegrass country of Kentucky, she must have ached for the familiar dark beams of a cruciform chapel.

Then, her mind muddled with age, she turned for comfort to the ritual of her childhood—the altar, the cross, the flickering candles — all beguiling symbols of her beloved Jesus.

She had warped my mind with her Latinate whisperings, her obsession with tokens. And I had come to hate her for turning against me when I rejected her notions. Yet she was only a simple farm girl, a hybrid in her beliefs, torn this way and that by opposing doctrines. I had never forgiven her, but now my vision was blurred with tears for my grandmother, named for the mother of Christ. She would have felt at home in this church, with the black-robed priest smiling comfortingly at her, assuring her that her sins were forgiven, that he would take her back into the fold. I had both resented and adored my grandmother, but I had never understood her anguish as she became an old woman and looked toward death, uncertain in her convictions. “Some have the gift of faith,” she said once. “And some don’t.” My two sisters, although active in the Church, had rather lukewarm feelings about the gospel, but Grandma’s needling had forced me to examine my beliefs, to delve into the scriptures until I had gained an undeniable personal testimony. She had been my unwitting gadfly.

Thinking too much of her and too little of the song, I fumbled on a few notes, singing “Ave, ave,” mindlessly, over and over, forgetting the words. Father Ashcraft covered my errors with his expert strumming, but he kept adjusting his vestments uncomfortably as though they were in the way of his yellow guitar strap.

In the darkening church, handkerchiefs were popping up like white birds. Was my memory lapse embarrassing or touching these people? A woman in the first row knelt, her black lace headscarf falling forward to conceal her face. Marsha ducked her blond head to pull down the kneeling board and, during a rest in the music, I heard it creak.

Now, a scattering of people were crossing themselves. There seemed to be a mass movement as the entire congregation knelt. I saw only a dark as semblage of bare heads, hats and scarves, and Bill’s upturned face shining solitarily from the rear, his fair, thinning hair illuminated by dying sunlight.

Was this sudden kneeling spontaneous or traditional? I wondered. Was there a certain point in “Ave, Maria” where Catholics automatically knelt and crossed themselves, just as it was customary to rise for the “Hallelujah Chorus?”

My breath gone, my voice died out after one count of the final note. I glanced quickly at Bill who was smiling ethereally, proudly. I knew he was thinking that I had become a missionary at last. In the second pew, Marsha dabbed at her cheeks with a brilliantly white hanky, the silver crosses on her charm bracelet glinting in light from a side window.

The faces of the congregation were turning up toward me as the sun’s fading rays tinted them with hues from the stained glass. I slid the absurd white hat off my forehead and pressed it against my protruding abdomen, relieved to be rid of it, wondering if I would be expected to bow.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue