Articles/Essays – Volume 38, No. 3

About the Artist

Throughout a long life, Robert Perine continually sought new ways to express his vision and use his creative gifts. Born in Los Angeles in 1922, he identified himself as a practicing artist from the age of six. Following military service during World War II, he graduated from the Chouinard Art Institute. He taught at the University of Alabama during 1950-51, then returned to southern California for a freelance career as a graphic designer. His most notable client was Fender Musical Instruments, for whom he created the legendary “You won’t part with yours either” advertising campaign. Although he attempted to maintain his focus on painting, his business, church, and family responsibilities dominated his attention for nearly two decades.

In 1969 he made a career change that allowed him to paint more seriously. Innovating with the medium he loved—watercolor—he departed dramatically and very successfully from its traditional use. During the 1970s and early 1980s, his work appeared in dozens of exhibitions and garnered numerous accolades. Among the institutions that own his work are the Butler Institute of American Art, the University of Massachusetts, Brigham Young University, Neiman Marcus, and the San Diego Museum of Art.

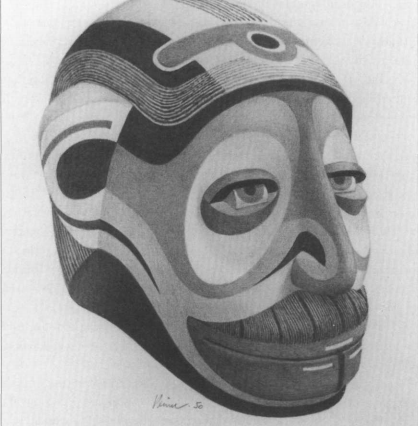

Eager to expand his creative reach, Perine expanded from painting to writing and arts activism, starting with writing and publishing the history of the original Chouinard Art Institute in 1985. Over the years, he wrote ten novels, several collections of short stories, three volumes of poetry, seven plays, and three musicals (for which he also composed the music). His last major art piece was an immense work called The Tribes of Xyr, which includes 372 graphite head drawings of

imaginary beings grouped into fifteen tribes. For each tribe he created a symbol, an alphabet, and a tribal history. Perine also wrote “Descent into Xyr: The World of Waterling Dilper,” a novella that details his encounters with this mythical world, located in an intricate series of caves in the high desert somewhere in the southwest.

In 2003, Perine was the driving force behind the opening of a new Chouinard Art School, where he was the director and taught watercolor, design, and figure drawing. Seeing Chouinard arise from the ashes was the culmination of a decades-long dream for Perine, who treasured the combination of creativity and art fundamentals the original school had provided.

Perine was raised as a non-affiliated Christian. His first wife was Mormon, and he joined the Church shortly after they married in 1947. They had three daughters: Jorli, Lisa, and Terri. He became active in the Laguna Beach California Ward during the late fifties and sixties, ultimately serving as bishop. In the aftermath of his career change in 1969, he and his wife divorced, and he left the Church. However, he continued to consider himself a Mormon—one who was not connected to a ward and did not go to Church but who valued its teachings. While he had many differences with the church, he also loved it deeply.

In 1979, Perine married Blaze Newman, an artist and teacher like himself, who nurtured his expanding creativity. He died in November 2004, of a sudden heart attack. He taught until the day before his death. Following is a tribute to Perine, given by his wife at the memorial service on November 13, 2004.

Tribute

Bob Perine knew what he wanted and pursued those things passionately. Our meeting 26 years ago appeared to be serendipitous but, in fact, he’d placed his order just a few months before. Lonely and searching for a meaningful relationship, he decided that he’d have a better chance if he enumerated exactly what he wanted in a woman. So, he sat himself down and wrote out a list of every trait he could think of. He wanted a woman who was an artist; Jewish; smart, funny, and feisty; with curly hair; petite; left-handed; between the ages of 30 and 40. The only part he got wrong was that I was only 27.

Born just two years after American women got the right to vote, Bob was raised traditionally yet was truly a feminist; he believed in the equality of women and lived that belief. He loved and admired strong women, luckily for me. His acceptance of my need for independence allowed me to flourish as a teacher and as a person. During the years when I was often at school from 7 A.M. until 10 P.M., not only did he never complain or even whimper, he was incredibly supportive. He’d help me with projects, mentor individual students interested in art, and even allow me to bring whole classes to our home on field trips, where he’d mesmerize them with stories of the Tribes of Xyr. After one such trip, a student gasped, “I never imagined there could be such an imagination.”

Bob’s deceptively conventional appearance hid an astonishing man whose imagination, wisdom, and spirit enriched the lives of everyone who met him, even though they may have spent only minutes with him. He combined playful ness with deep spirituality and a sensitive understanding of people. Fundamen tally, he was the cock-eyed optimist, with a profound belief in human decency and the ultimate triumph of justice. I remember his telling me about the day in 1978 when he heard that the Mormon Church had lifted its ban on blacks in the priesthood. He was driving on the freeway when the news came over the radio. Bob had to pull off the road because he couldn’t see through his tears of relief and pride.

He loved all types of mental challenges, from crossword puzzles and Scrabble to teaching himself to write in his mid-fifties, from developing a radical new use of watercolor to opening and running an art school just last year. His mind was his favorite toy. Many years ago, he wrote: “Tomorrow has a new name and a new thirst.” Embracing that “new thirst” gave him an astonishing capacity for growth, regularly reinventing himself and developing his boundless gifts. I used to call him “my little Zen master” because he lived so fully in the present. Neither the past nor the future were terribly important to him. Sometimes that trait infuriated me because he wouldn’t consider possible consequences of an action, but ultimately, I knew that his focus on “the now” was a major part of his apparent agelessness and of his genius.

He could be stubborn as a mule but his sense of fair play forced him to be open-minded—eventually. I still remember the night I took Shrek out of the red Netflix envelop. He scoffed at the idea of watching an animated movie—those were for children. I told him to trust me and pushed “play.” After two hours of giggling, gasping, and guffawing, as the credits rolled, he said, “Disney, eat your heart out.” The following week, he bought the DVD and we immediately watched it twice more. He sat friends down and said, “You’ve got to see this.” In all, he watched Shrek at least six times and could barely wait for the sequel. It’s a small story but embodies his breath-taking flexibility as well as his appreciation for quality work.

About his own work, he wrote, “As an artist, my job is to entertain the eye. My images are not responses to cultural shifts or social injustices I cannot fix. Art is more than reaction. Like peace, I see it as an antidote to human anxiety. It offers new ways of stimulating thought. It’s about retoring equilibrium, transcending a world too complicated to manage. I think of the rapport between artist and viewer as love incognito—a mystical, spiritual seduction.” And all of us here today were seduced—by his capacious mind, his extraordinary visions, and his boundless spirit.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue