Articles/Essays – Volume 09, No. 2

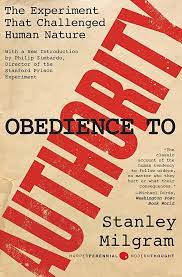

Acting Under Orders | Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View

What do we do when we have agreed to participate in an experiment under the auspices of a prestigious university (and are getting paid for it) and we are asked to do something objectionable? The Ph.D. experimenter instructs us that this is a research project studying memory and learning. He explains that we are to be the “teacher” and another volunteer will be the “learner.” Since the experimenter is concerned with the effects of punishment on learning, it will be necessary for us to “shock” the other subject every time he makes an error in learning a list of word pairs. Additionally, as he makes repeated errors it will be necessary for us to increase the electric shock intensity. The “teacher” and “learner” are in separate rooms with an observation window between them. The learner is seated in a chair with his arms strapped down to prevent excessive movement, and an electrode is attached to his wrist. The teacher in the adjoining room is seated before an impressive shock generator with a line of thirty switches, ranging from fifteen volts to 450 volts with verbal designations above ranging from “slight shock” to “Danger —extreme shock.” As it turns out, the “teacher” is a naive subject who is the real focus of the research while the “learner” is an actor who actually receives no shock at all. The whole point of the experiment is to see how far a person will go in inflicting increasing pain on a protesting victim.

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram has authored a fascinating book focusing on an area of interest to many Latter-day Saints: authority. At what point will the subject refuse to obey the experimenter, a prestigious authority figure who constantly urges the “teacher” to increase the shock intensity? This, of course, raises memories of Nuremburg, reminding us that ten million Jews and many foreign workers were gassed during World War II by hundreds of compliant Nazis because “somebody above had ordered it.” To what extent will a person acting under authority perform actions which violate his conscience? Thus we have a basic dilemma which faces all men on occasion, the conflict between conscience and authority. The bishop requests that we participate in a project that we are thoroughly opposed to. The government orders that we fight in a war which we personally feel is immoral and illegal. What do we do?

As might be expected, Milgram’s findings show a great variation in the “teachers’ ” willingness to shock their victims at high intensity levels. In some of the sessions, the “teacher” could see and hear his “learner” cry out in pain, furiously protest and writhe as the shock levels were increased, but still administered more shocks to the highest levels possible because the experimenter insisted on it. If the choice was left entirely up to the subject, he usually shocked at the lowest levels possible. If the “teachers” had peers or associates (as “co-teachers”) who suggested noncompliance when the experimenter urged high shock levels, this contributed powerfully to their refusal to continue on.

What are the implications of this research (and its many variations discussed more fully in the book) for committed Latter-day Saints who believe in unswervingly obeying God’s commandments, following the Brethren wherever they might lead, and not speaking evil of the Lord’s Anointed? The most probable answer to most of these questions is that most Latter-day Saints, if asked to do something evil, morally wrong, or injurious to others, would not do it. Ultimately, one’s conscience and the Holy Spirit of Truth must confirm and bear witness that a particular act is right and proper, regardless of who requests that we do it. Hope fully, we have been taught “correct principles” and we would usually govern ourselves reasonably and humanely. Such minor matters as being requested to work on a stake farm project which we may feel is a waste of money or energy do not present a serious moral issue. On more serious matters, such as practicing polygamy, even though ordained of God, the free agency of participating members was a vital element to all concerned. And while some exceptions might be cited, the basic rule was “informed consent” and freedom of choice.

It is certainly remotely conceivable that a mission president, stake president, bishop, or other individual in high authority could have a psychosis, such as say paranoid schizophrenia, wherein he might request those under his authority to do improper things. However, any kind of extreme or bizarre behaviors would be quickly noted by his counselors, family, or associates who within hours or less could seek counsel of higher authorities who could in turn request hospitalization, release him from his Church position, or take whatever other action was necessary to neutralize his influence. And in actual practice, when a member of the Church at any station of life or priesthood feels that his immediate ecclesiastic superior is “out of step with the Lord” he can discuss the matter in confidence with the next higher authority. Or he can “sit it out” and do nothing—as many senior Aaronics and inactive elders have done since the Church was organized (but usually for reasons other than “conscience”).

I believe that it is possible for any person, regardless of position or station in the Church, to be corrupted and “fall.” King David, Judas, and Oliver Cowdry all attest to this, as do numerous examples known to all of us in our personal experience. But I do not believe that it would be possible for the entire Council of the Twelve to fall from grace at one fell swoop, even though individuals on the Council might fall (as has happened on several occasions since the Church was organized). Each man on such a council serves to cancel out the human weaknesses and per sonal idiosyncracies of his fellow members. This serves as a corrective and purifying influence to protect the sanctity and integrity of God’s will, if you wish. Even though each man acts as a lens with some distortions and imperfections which will to some degree distort the inner light (Holy Spirit) as it shines through his personal spiritual nature, when consensus is reached by such a body it ordinarily represents a highly distilled essence of truth. And the same psychological processes are at work in a ward priesthood quorum or relief society. In the extremely unlikely event that some higher authority were to request ward members to do something immoral, improper, or anti-social, the collective conscience of the group would not tolerate it (as in Milgram’s experiment) even though one or two might be misled. This, however, does not mean that small groups on their own can’t—like cancer cells—become corrupted. Though rare, it sometimes hap pens under certain psychological stress conditions as at My Lai, with a lynch mob, or at Mountain Meadows.

Admittedly there have been historical apostasies of the major Church organization. This, however, has always been a slow corroding process. Also splinter and apostate groups (including a few missionaries in the French Mission several years ago) have broken off and established their own brand of True Religion. The test that can be applied to the legitimacy of their authority (in addition to logic and good judgment) would be “by their fruits ye shall know them.”

Love and long suffering are the major methods in the LDS Church of winning converts as well as keeping them with the ever-present influence of the Holy Spirit to guide and inspire. Coercion and threats of damnation and eternal fire as methods of behavior control are for all intents and purposes unknown in our Church. I would see the specter which Milgram raises as more appropriate to political and military organizations than to most religious sects. One can imagine some difficult moral choices facing Church members who live in lands controlled by dictatorships, where one might be conscripted to serve in armies or police actions and where being a conscientious objector would not be a permissible “out” to avoid participating in evil enterprises. Ultimately each person will have to struggle with these moral dilemmas on an individual basis. After all, LDS theology suggests that this earth life was purposefully designed as a testing ground, a vale of joy and fears, a place of struggle and growth, where goodness and evil would co-abound and compete for our allegiance. This is still earth, not heaven.

Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. By Stanley Milgram. New York: Harper and Row, 1973. xvii + 224 pp., $10.00.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue