Articles/Essays – Volume 44, No. 2

American Trinity

The other two are more patient than I am. They bide their time. What’s worse, Jonas is always telling me that I am shirking my duty. I haven’t talked to him in over a century. Hundred and fifty years the last time I talked to Kumen. Even though I have returned to my mission of wandering and ministering, both would insist I’ve lost the spirit of the assignment. I avoid them now. I was just coming out of the Empire Theatre in Old New York when I last talked to Jonas. Word must have gotten out. Like myself, Jonas was dressed as a patron in tuxedo and gloves. Courtly old Jonas. “I like the collapsible opera hat,” I told him. “Nice touch.”

“You’re playing with me, Zed. That I should even feel compelled to be here is an embarrassment.” He looked about wild eyed at the throng of velveted ladies and their escorts climbing into broughams parked under gas lamps.

“How long has it been?” I asked, putting on my own gloves. “The courts of Montezuma?”

“We go where we are called to go,” he intoned. Then he looked at me, bemused. “You’re the one holed up in the theater district. Shameful.”

“Yes, but isn’t it interesting that every time you decide to make an appearance, it’s where there happens to be a lot of social position? A lot of pretty ladies?” I said, nodding in the direction of another exiting entourage. “Even if it is an embarrassment.” Jonas looked at me with practiced contempt. Then he asked me for one of the new manufactured cigarettes, for which I had recently given up my pipe. Convenience . . . plus I’d needed a change. Any kind of change. We walked down 40th Street, stepping over muddy wagon ruts.

In the restaurant, Jonas ordered wine and oysters while I smoked and studied the lace drapes on the windows behind him. Unlike Jonas who covets the world’s beautiful artifacts, I am simply amazed that the living-who-will-die go to such efforts to create it at all. The crystal chandeliers brought over from Old World Bohemia. The coffered ceilings of the rich. During the centuries of catastrophic Nephite wars, a man would intricately etch his sword as if his life depended not so much on the might of the metal, but on how beautifully it could kill. But as my two colleagues and I, left behind by edict, moved through the carnage with our amulets, our consecrated oils, our prayers, there was no way to see the wounded as dying beautifully.

Even when I was in Old New York with Jonas, the senior one, and eating oysters, I had surmised that this life we led was the way it was always going to be. For the Three Nephites, this was it. There would be no return of Jesus to mark the end of days and the end of our mission. That was why I was going to the theater—to escape. After three glasses of wine, I told Jonas that.

“You’ve lost your faith,” he said.

“I’ve lost my life.”

“Nonsense. The Lord has kept His promise to us. We are still here, aren’t we?” He took another sip from the finely cut crystal glass and returned it carefully to the table. He leaned back in his chair and breathed in the night, then continued as if it were an afterthought.

“You’ve been here since the days of Zarahemla. A full life for us, if there’s ever been one. We had families, children. Gave them our blessing before they went—”

“No,” I interrupted, “you had children. You watched them die of old age. I had no children. I was always alone. I’m still alone.” Jonas shook his head at me, the rims of his eyes pomegranate-red. I’ll admit, when I received the calling nearly two thousand years ago, it seemed like a good idea—minister to the earth’s inhabitants and then, at the second coming, go right into heaven, “in the twinkling of an eye,” as The Book says.

“Perhaps you’re lucky, Zed,” he finally said. “It was merciless to watch my grandchildren die of old age. Even more so to see their grandchildren slaughtered needlessly.”

“Maybe it was needed. Part of the history that must be written?”

“That’s not what bothered me. There will always be wars. No, it was how they turned against themselves. And those bastard robbers,” he spat, referring to the Gadianton Robbers which still existed, a parallel order held together by secrecy and oaths and by the constant manufacture of an outside enemy to distract the people. In Old New York they were now called magnates. “Each of us is alone, Zed. You, me . . .”

“Not Kumen,” I mused. “He has his fans.” Jonas sensed my attitude. I had been watching too much Restoration drama, and I was becoming a cynic.

“He likes it out there.”

“He likes the desert,” I said. “Unlike you.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s probably eating locusts right now, on principle. Not exactly hot terrapin or oysters.”

“We go where we are called to go,” he repeated, annoyed.

“And also where there happen to be urban wonders and warm baths and . . . bottles of Bordeaux.” I lifted my glass. He reluctantly toasted.

“I’m doing my time,” he said.

“It is more like a sentence than a promise. And it’s not over yet.”

Jonas sighed, and pushed his plate away, the outline of his moving arm blurring ever so slightly in the air. It is the only feature that might distinguish us from others, a sort of full-body halo that lightly pulses around each of us and can only be seen by children and the occasional drunk whose vision is already failing at the edges. I am told that around my inexplicable red hair and fair skin the hue is pink.

“I really thought it was all about to end with the new age of prophecy,” said Jonas.

“Never pin your hopes to a seer who secretly takes multiple wives. And in Illinois, no less.”

“At least he translated The Book before he was gunned down. We have that, thank God. Maybe the end times are upon us after all?”

“Or maybe it’s just a tease. A cosmic burlesque.”

“You are a bitter man, Zed,” said Jonas, and he drank the last of his wine. “Are you going down to the docks tonight?”

“I suspect there will be the sick to attend to. Where else would I be?”

“A box seat back at the Empire?” Now it was my colleague’s turn to call my bluff.

That was in Old New York, which doesn’t exist any longer, and perhaps never really did—with all of its privileged, just another version of the Gadianton Robbers, this time in spats. It was the last time I saw Jonas. Well, there was the Triangle Fire twenty years later, but I couldn’t bring myself to speak to him then. I can always find him if I need to. But what do you say to someone you’ve known that long? Two thousand years as the American Trinity—it breeds contempt. But it’s contempt with a residual ache for one another. So we routinely seek one another out, trapped as we are somewhere between deity and humankind. Mortal but unable to die. Angelic in our transport but plodding in our flesh. Embalmed alive. All of it set forth in The Book, the sacred history of the American continent.

Our story may not have a stirring ending—an ending at all— but it has a fabulous, inventive beginning. By the time I was born in Zarahemla, twenty-five years before Jesus made His New World appearance, my people had largely fallen out of favor with God; and in the turmoil, the Gadianton Robbers could wreak their havoc.

In the midst of their intrigues, I was busy working in the temple scriptorium, a library of worn parchments. We were attempting to abridge them to something more permanent and had to compete with the armory for gold and other metals. I didn’t think we needed another sword, another shield, however beautifully wrought. What we needed was the story. I actually paid attention to all the old tales I was transcribing. And I imagined what it was like to be one of my Hebrew ancestors, clambering into a ship and making the great journey from the Old World. I made a point of infusing the accounts with the requisite miracles.

There are worse things than doing that.

I was too slightly built to be a warrior. So I became the hands to my old mentor Omni whose fingers were permanently balled and ruined. He’d always seemed to care more about the written traditions than about war. And so did I. His work was to tell a story, to reset old writings into the plates of soft alloys and to interpret them for our day. Omni made us all part of a continuing story.

“Show me a people who don’t feel connected to their own biblical saga,” he told me once, “and I will show you a people doomed to destruction.”

But now, with the last of the precious metals needed for the war effort, the temple scriptorium was under siege. And Omni was failing. Lost in a fever, he lay against pillows in the corner of the room while I continued frantically to pound into metal the text from the papyri so that my own fingers had begun to curl in on themselves. When the metal plates were complete, I bound them with rings and sent them out to be hidden from the enemy of the hour. You see, for the Gadianton Robbers, it was always a classic “let’s you and them fight.” The Nephites were a nation hopelessly divided, and all the robbers had to do was give us enough rope and wait. That, and use our own schismatic warriors to do their dirty work. In fact, it was these warriors, lusting for gold, who were converging on the temple.

I heard voices outside. Before giving the last of the plates to the courier, I placed my hands on them and offered a prayer to the Nephite god for their protection. Suddenly, there were men everywhere in the room, their thick legs wrapped in leather and metal, their spears towering above me. On their heads they wore the traditional Nephite helmet, but their faces were striped with Lamanite paint. When they didn’t find what they were looking for, they left, except for two of the men who took off their helmets and looked at me savagely. I knew it was my hair, an anomaly. Their mouths were wet and red with wine, their own hair long and tangled.

“You!” bellowed the bigger of the two. “Hiding yourself here with a worthless old man who steals our gold while we fight his wars!” And with that he took his spear and slowly pressed it through Omni’s chest so that his eyes opened wider and wider for one revelatory moment while he reached up with both arms as if to embrace a phantom deliverer. I could not go to Omni. Was it because I knew it wouldn’t do any good? Or was I just afraid? Words, however, never failed me.

“Your wars have become the games of boys,” I screamed, thinking I could shame them into silence. “You are Gadianton’s lackeys, fighting for your own illusions and your own pleasure in death.”

“Today you will die!” the warrior shouted.

“No, you will die—and all of this,” I said, gesturing at the room of now scattered papyri and metal filings, “will be the only mean ing left to your vandal lives.” That’s the way the story goes. How it got recorded. Omni pinned against crimsoned pillows, my fear turned to outrage. The thugs were not interested in meaning, however, even though they were silenced, if only for a minute before moving in on me, patting my head as if I were a house dog.

They took me by the hair, spread my legs, and raped me. After that, I knew I had to believe. The prophecies of my people needed to be real instead of just a beautiful literary device. They needed to be something that took place in real space, in real time where truth and accuracy aren’t always contingent. The prophecies were that the Messiah was coming now, in a local appearance. That is how I remember it, through the record that now exists as The Book. That the Messiah would save me, Zedekiah, the red-headed scribe with the small hands.

Nothing like the grinding of another man’s hips into your own for the word to become flesh, to believe. And it was clear what I needed saving from—an invading army, crashing through our homes and temples, and imbibing our blood.

And so it came to pass that the Messiah did come, out of the sky—a pinpoint of a man dressed in white and descending as if on a wire through a sky so dark that it was said you could feel it. In the ruins of the city, he stood, stretched out His arms, the wounds in His hands and in His feet still luminous and purple. He was the most beautiful man I had ever seen. He came, and there was peace and prosperity (in the parlance of our time) even if it was for only a few years which would have suited me fine had I died within a man’s life span. The span of life portrayed so well in the theater.

On stage it’s like this. What counts is not so much what happens, but the arc of what happens between curtain rise and curtain fall. And, chiefly, there is the ending, a luxury reserved for those who will die. It’s no mystery to me why, instead of tending to the needy or worse, slogging through the battlefields of collapsing nations as I am supposed to, instead I sit clutching a playbill and watching the drama open, build to a climax, and then end. The blessed ending. Maybe that’s why, earlier, I cared so much about The Book. It had a life of its own. And it had to be recorded by someone—to be shaped. And so it was, by me.

I think there are worse things than fudging history. Like not having a history worth reading at all. I know the record kept changing because, for a while, I was the one doing it. He wasn’t Jesus when he made his appearance. He was the Nephite god, and I’m okay with that. The story needing to be told was that we were Christ’s “other sheep,” destined to be brought into “one fold” with “one shepherd.” I expected to continue as scribe, but then I was called to be one of His chosen disciples. Me, the small one with hair of fire. I was promised immortality as a kind of assist in the New World. Of course, I had to give up possession of the record, but I had had my time with it, and I refuse to complain about the scribes who came after me.

Okay, maybe I will. It’s just that, as a scribe, I had a certain sensibility, a respect for the language, a sense of the record having continuity. Unlike Mormon. I can never forgive his imbecilic pruning of whole centuries of the story. “This army went here, this army went there . . . and it came to pass . . .” In his hands, a history became a kind of strident, outdoor pageant. He even cut the entire episode about Omni and the scriptorium. Granted, he was pressed for time during those final, desperate years of the Nephite nation. But did The Book have to be named after him?

“I have constraints of space and time,” he kept telling me. And I would badger him, reappearing over and over in his tent, once five times within the hour.

“You’re possessed,” I told him once point blank. “You’re possessed by military maneuvers.”

“I’m a warrior,” he would bark.

“A prophet-warrior. Like David, maybe?” I would suggest to him—to inspire him.

“He was no prophet.”

“He was a poet.”

“He was no prophet.” Mormon was right about that. In fact David had forfeited any ready communion with his God. That’s what made his songs so beautiful. The longing. The abject misery at being cut off. I like to believe that in the hereafter God will make an exception for a poet.

Maybe my hope for David is hope for myself. Maybe it was my hope for The Book that Mormon was hurriedly pounding out in condensed form from the voluminous old plates of Nephi—some of which I had translated myself in the scriptorium. The hope was that our mystical story of God’s leading us from danger to a promised land might rival the Hebrew record brought out of Jerusalem by Father Lehi and the clan, even the Torah, or “Bible” which is today cherished above all other histories. Without our own inspired, and inspiring book, those of us residing in the new world would always be relegated to the step-sheep of God.

“We are more than just the sum of our battles,” I would say, and storm out of Mormon’s tent. Eventually, he got back at me. In his account of the three of us, left behind to walk the earth for century after dreary century, the old warrior-editor quipped that he had seen the three of us, and that we “ministered” unto him. I can’t speak for the other two, but I did not “minister” unto Mor mon. Harangued him was more like it. I was the one possessed by something. Mormon was about to die in battle, and I was worried about translation, emphasis, what certain people would eventually call hermeneutics.

Maybe we are the sum of our battles. But my battles are interminable, it seems, my immortality a curse. Before He rose to heaven, the Nephite god promised the three of us that we wouldn’t die until He came again in glory to the whole world. He said, “And again, ye shall not have pain while ye shall dwell in the flesh, neither sorrow save it be for the sins of the world; and all this will I do because of the thing which ye have desired of me, for ye have desired that ye might bring the souls of men unto me, while the world shall stand. And for this cause ye shall have fulness of joy . . .”

Joy. But when? The text is maddeningly unclear.

I remember little more about the Lord’s sojourn with us than what anyone else can currently read, and I was there! That’s what you call the power of a text. So what I was fighting Mormon for was nothing less than my existence, my identity as a disciple of a god who battered our hearts into newness—not just micro-man aged ancient Meso-American battles. Mormon has gone on to his end and his reward. But all that I am, stretched out like a string over two thousand linear years, is in the permanent record that got left behind. I am the one ministering around—longing like David—for some kind of ending to the story that I am still living.

It certainly doesn’t feel like “fulness of joy.” Jesus must have meant that joy would be our eventual reward. After we are “changed in the twinkling of an eye” at His second coming. I’ve had a mind to track Him down, to demand closure. But I am afraid it might demonstrate that I have lost my faith, as Jonas says. Maybe I am just terrified of what my Lord would tell me.

None of this seems to bother Kumen. When he reads the one account of who he is—one of three Nephites left to wander and bring souls to the Jew Jesus who became Christ, the Son of God, and then God himself—he accepts the catechism without question, shedding all personal feeling, all memory. Like a coat.

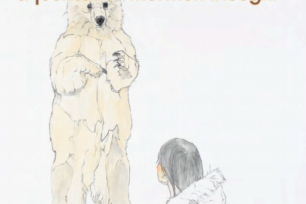

For Kumen, it goes like this. A Jew or a Gentile—either one—gets into trouble. Kumen floats around until he finds one of these souls, believer or no, and he materializes. Brings a flask of water to save the dying-of-thirst, presses forgotten consecrated oil into the palm of the healer, enters the cockpit of the tumbling jetliner. He saves the day. Then, he dematerializes before they turn around to say thank you, vaporizes with their despair. This is the sign, the guardian angel thing.

I get the idea that this tickles old Kumen pink. Being sneaky, formulaic. I call it guerilla ministering.

“How do you know if that leads them to greater faith?” I asked him once in 1871, years before my dinner with Jonas. I had just seen a show called Buffalo Bill in New York and become curious how accurate the stage story was to the American West. So I just “happened” by one day in the Sierra Nevada when Kumen was about to blast through to a gold digger trapped in a mine.

“Of course it leads to greater faith. If you saw a miracle in front of you, what would you think?” I lit my pipe—still my prop at the time—and followed him into the mine, unseen. The man, in a fetal position, lay near crumbled rock, his head darkly matted with blood.

“I might think it was Buddha, if I were Buddhist. Or if I were a superstitious Muslim, a jinni. That’s not exactly working the program, if you know what I mean.” Kumen took an amulet from his threadbare coat and placed it on the forehead of the man whose dusty eyes opened to the miracle above him. Kumen offered a prayer in the Adamic language that featured some impressive sounding diphthongs, then he smiled gently at the man who sat up, the light from the lantern reflecting off the beatific face of my colleague.

Oh, the look in the miner’s eyes! Even I got choked up.

“The problem with you, Zed, is that you are a humanist. You have no sense of what’s absolute,” said Kumen outside the mine where it was so bright that I instinctively manufactured a broad brimmed hat to protect my notoriously pale face from the sun’s rays. He slapped the dirt from his dungarees. Kumen had no idea what “humanist” meant. But he liked to use the term as a battering ram. “People just want to feel better in the moment. They don’t want to actually solve their problems.”

“Some of us want to solve our problems,” I said, puffing on my pipe. I followed him east, holding my hat in the arid wind, to the pioneer settlements of the Ute Territory, where the people of The Book were congregating. Though he was third in the Trinity, he was the most diligent of the Three Nephites, based on the account of who we were supposed to be. As usual, I fell into the role of nag and hated myself for it.

We were standing outside a makeshift adobe hut. A polyga mous woman came to the back door to shake out a rug. Kumen was there, asking for food. He knew, as she did, that there was only enough corn meal to make one small flapjack for her two hungry children. She took him in anyway and fed him. There was unanswerable pain in her sunburned, twenty-year-old face, a dissolute pain kept in check only by the ignorance of youth.

“Thank you, sister,” Kumen said after his humble meal. He tipped his hat to her. When he left, the grain bin began to glow, and I knew what Kumen had done. A textbook miracle. She raced to the door to see who this strange figure was, but he was gone. Of course. We watched as she fell to her knees and wept.

“I’d say that woman—Sister Leavitt is her name—I’d say she has a life full of faith ahead of her,” said Kumen, and he smiled. “That’s what’s real, Zed. Giving them something to believe in.”

“What about follow-up?” I asked, folding my arms across my chest.

“Being able to tell her sister wives this little story about one of the Three Nephites appearing to her in her hour of desperation is all she’ll need to carry on in this life. A scribe, in the year of our Lord himself, like you, should understand the power of telling a story.”

“It’s not that,” I said. “I question your motives.”

“There is no need for me to question my motives if I’m doing what I was called to do. We must be in the world but not of it.”

“But you’re doing all of this by rote. Maybe the reason people don’t try to solve their problems—to really transform—is that they sense that for you there’s nothing outside your silly standards. Not even their own experience, for heaven’s sake.” I could see that Kumen was losing patience with me, but I couldn’t resist. “The interaction may be as much about you as it is them. Maybe they’re supposed to change you as much as the other way around. Ever consider that?”

“The dogs bark, but the caravan moves on,” he snarled, then reached over, ripped the pipe out of my mouth, and threw it to the ground. “Why would anyone take you seriously with that bowl of filthy weed in your mouth?”

“What do you remember Jesus’s directive was to us?” I demanded, nonplussed.

“It’s not what we remember His directive to be,” Kumen said. “It’s what the directive was. You’re like one of those Unitarians, Zed, so imbedded in the world that they’re always distorting everything.” He sighed. “You know as well as I do that it was to bring souls to the Christ.”

“But what does that mean? Do you ever question what—”

“It means what it meant for us,” he shouted. He clutched at his chest, breathing hard.

“But I don’t remember what it meant to me,” I said. “Not really. And maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Maybe that creates an opportunity for us to redefine what it means. To tailor it to the circumstances, to the individual.” Kumen sat down, still clutching his chest. He always did this when we debated doctrinal matters, apparently forgetting that we’d been promised we wouldn’t suffer physical pain. I used to find it cute the way he would pant and moan, talk about his palpitations. But this time I was just annoyed. I looked around for my pipe.

“Do you know how much work you’ve avoided by fretting over details non-stop?” he said finally. “You’re a sophist, Zed. A Gadianton Robber.”

“Gadianton?” I spotted it, next to that rock.

“Exploiting the situation. Sabotaging the work. Sneaking around and sowing seeds of doubt, not change . . .”

“I’m entitled to a life, to my own experience, damn you. And don’t forget that it was I who kept The Book from getting into their hands. That’s what they wanted.”

“And what have you done since then? I tremble to think of how disappointed in you the Lord is, Zed. The way you snivel all the time—it’s enough to make me sick.”

“Maybe the Lord is disappointed in you,” I said, tapping the back of my pipe against my palm. “Your fly-by-night ministrations. Your—your sentimentalizing of Him into some kind of long-haired celebrity.”

Kumen stood up, and I knew I had pushed him too far. He brought his right arm to the square to denounce me. “By the power of the Melchizedek Priesthood, I forbid you to demean our Lord and Savior.”

Now that I was denounced, I had to leave. At least for the time being. That was the rule. So I did, muttering to myself and ashamed for mistreating one of my own brethren. Kumen always used that against me. Not the arm-to-the-square thing. No, he would question my character, my commitment.

Maybe Kumen is right. Maybe my sins are the greater, held captive by my own game. It wasn’t the altruist in me that found the calling appealing or even the desire to share the taste of salvation. Maybe it was just that never dying would mean I could spend time pegging others—Kumen the fundamentalist, Jonas the executive—so that I would never have to peg myself as anything. What I didn’t anticipate was that I would not only end up utterly alone, but that I was going to have to learn what it meant to die without ever actually dying.

And what better place to learn how to die than in the theater? Medea, Hamlet, Dryden’s All for Love, the title of which says it all. That’s when I took my little “holiday” as they say, which is why Jonas showed up outside the Empire Theatre to reprimand me. But I wasn’t ready then to give up the theater and its artificial but seductive modes, and I didn’t. Not until later. There was the stage at night, and the streets of New York during the day. I would look at the arriving immigrants, pathetic, frightened things, and wonder if I could extend the meaning wrought by the stage onto them and thus onto me. I thought maybe they held some kind of remedy to the agony of my loneliness in the promised land.

It was 1911, and I was still in New York. As I walked down busy 26th Street, I heard fire alarms, four of them in fifteen minutes. By the time I arrived at the Asch Building at the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street, several small bodies had already shattered the glass canopy covering the sidewalk and were lying still against the hard pavement. All around, as the fire trucks arrived, horrified people were screaming “Don’t jump!” at the girls huddled in ninth-floor windows that were pouring out smoke, a hundred feet up. But jump they did, some holding hands, their burning dresses blowing up over their faces, one dress catching on a wire where the girl dangled before the cloth burned through and she thudded to the ground.

Even I, who had ministered ankle deep in blood to the slaughtered Lamanites in Central America, I, who had cared for the Africans in the dark holds of slave ships, I, who held up the lolling heads of the bayoneted bodies in Lincoln’s War—even I could hardly stand to watch children burning and falling while adults stood helplessly by. Then it occurred to me that all of the sidewalk crowd was an accomplice to this tragedy. An accomplice to an age that not only conveniently clothed and fed us but kindled this fire as well. And I, too, was an accomplice to this event just as the Nephites were to their own extinction.

I took off my jacket and hat and walked up to the largest pile of bodies lying in a pool of water from the firehoses. The firemen had no time to attend to what looked like the dead, for a dozen more of the terrorized girls were still getting ready to jump through the smoke and haze and through the hopelessly futile fire nets, falling like overripe fruit dropping to the orchard floor.

I sensed that someone was alive in the pile. I wormed my way through the corpses, through arms and legs, bloodied and crushed, and near the bottom to where a twelve-year-old lay, her body twisted. Everywhere was the smell of smoke, of burned hair, of moistness all around. She lay quietly, her eyes open and afraid, her crushed chest still somehow rising and falling. I lay next to her and held her in my arms and tried to remember my prayers through fear that seemed to vault to the height from which my new charge had fallen. There was the little-girl smell in her skin, so different from that of boys, and I pressed my lips into the top of her dark, tangled hair.

“The finished shirtwaists caught fire,” she whispered. “They were all above us, and they burned off the wires and fell on top of us, and the trimmings on the floor caught the fire, and the elevator was blocked and there were only windows.”

“Were you afraid?” I asked. She could not look at me, because her neck was broken, but I could see the sudden sadness in one of her eyes.

“I was afraid when the others jumped. When I saw them fall to the ground. It was not so bad when I finally did it. Am I going to die?” she asked finally.

“You are going to die,” I said.

“Then I shall pray,” she said, and it was then that I saw in her other hand a book in Hebrew she had obviously taken to the window and clutched during her plunge. She groped at the pages with one hand and her lips began to move. I held her tightly, making myself as small as possible under the pile of bodies—just large enough to do my duty, to see it through, while the final scene of her life closed in around her. I wanted to be a witness, and maybe if I was lucky, to be a kind of comfort, to hold the only kind of child that would ever be mine—a dying one.

She stopped praying, and for a moment I thought she had passed on, but then I felt her hand reach up and touch my face. Without knowing it and against all the rules, I was crying, and she had felt my shaking. She offered a prayer that I neither heard nor understood but simply felt through the points of her two small fingers pressed into my brow.

“Don’t be afraid,” she finally said.

When the men reached her, she was still breathing, but two minutes later, she expired. I watched as her spirit rose out of her, thinning to a shining thread, her outline momentarily blurring in the air. Blurring as ours does.

As they carried what remained of the girls away, Jonas was there, standing to the side of the crowd still milling across the street. As always, he was alone. I looked at him for a long time, ashamed, but somehow renewed at the same time. Had he come to discipline me, this senior member of the august Three Nephites? Discipline me for losing my composure while on duty? I turned away, looking up one last time at the now silent building, still intact. When I turned back around, Jonas was gone.

And so it came to pass, I gave up the theater after the drama of the 1911 Triangle Fire. In the theater, there is too much vicarious life on stage, thrilling in that pre-digested way—but instantly dismissible once you walk out the door. I hear that theatrical entertainments are quite the show now. With the invention of moving, lighted pictures on a screen, our relentless industrialization has turned technological. And dramatized illusions are so mesmerizing, they say, that daily life for some has become the intermission between cinematic moments. But illusions as such would have no power over me today, having simply made it obvious that the meaning of our lives has always been a construction. As in The Book.

That is why, today, I am no longer waiting for His return. I am going in search of the Nephite god, the Savior of the world. I must see Him again.

It isn’t as hard as I thought it would be. He is nearby, asleep on an antique, four-poster bed and, lying there, He has that half-levitating look of someone dreaming, His body outlined under a sheet. I wait for him to wake; and for a moment, I feel again the ancient stirring in my heart from the days He lived with us. The adrenaline. The infatuation. Desires unaccounted for. But then I realize that, out of His setting, it just isn’t the same. He is slighter of build than I remember, the shape of His face less angular, less strong. Freckles on His arms and chest. And the five special wounds on His hands, feet, and side are now scars, mere plugs to the punctures I once touched with my own hands. To touch Him, to touch His wounds, was to know that He understood me, what it had been like for me not just to be raped that day in the scrip torium, but all of it, to be the outsider with strange gifts and even stranger desires that never fit the way of the world—desires in the mind and in the body. To be childless. To be chosen as one of His New World disciples because He felt sorry for me.

“I want to die,” I say to the sleeping form. “I want you to release me from my mission. I have seen too much. I’ve been here longer than you were.” He stirs slightly, lifting His arm up over His head and twisting in the bed. I can hear His breathing, see His chest rising and falling slowly, the chest whose warmth I felt when He ordained and blessed me before he left us. But now, I feel old enough to be the father of this sleeping god. That I have more to tell Him about His life than He can tell me about mine.

“The threat from the Gadianton Robbers was never disbelief, or even secret wars,” I say. “No, the real threat was that there would be no record, no book to find oneself in. That was what they wanted to destroy. Not ourselves, but our literary selves. I may not be a believer like Jonas or Kumen, but I believe in The Book. I fought over how it got put down. Listen to the words: ‘The time passed away with us, and also our lives passed away like as it were unto us a dream, we being a lonesome and a solemn people, wanderers, cast out from Jerusalem, born in tribulation, in a wilderness, and hated of our brethren . . . wherefore we did mourn out our days.’

“I made sure that passage survived. That was my work. So that there would be a record of how it was like for this people. Of how we read this life.

“That was why I loved you. When you were among us in the flesh, you read my heart. I thought you could see through this smallish, irritable man to one who loved the word, and the idea of you, and your grand entrances and exits. Who loved your continuity from beginning to end, from ministry in the Old World to ascension in the New. The way you died. Your curtain calls. The way you sleep and dream now.”

There are tears that suddenly water His image lying before me, washing the scene of any grand mystique. What I want is not the same as what I need. And so I cry for the lost Nephite that I am, and then lean and kiss my Lord good-bye, not as I want Him to be, but as He is.

The sleeping god smiles, and now I can go.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue