Articles/Essays – Volume 31, No. 4

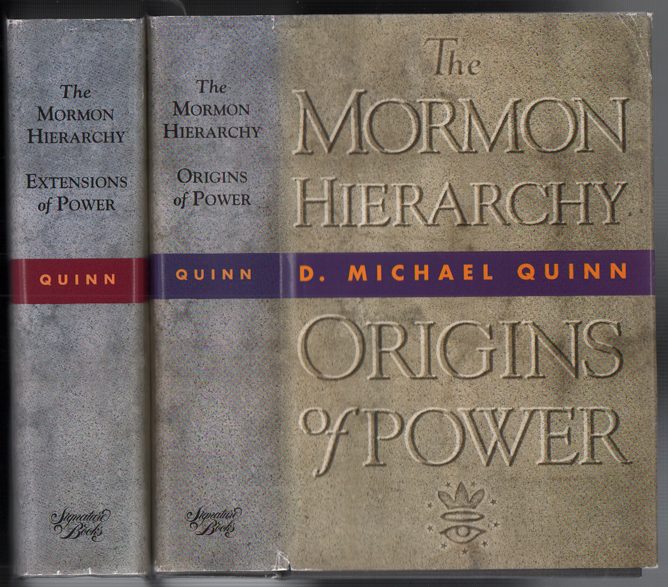

An Extremely Consequential Contribution | D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power, and The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power

These two volumes aim to describe the development of the hierarchical leadership and organization of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon) as well as certain related issues. They begin with the “private religion” of the founding prophet, Joseph Smith, Jr., and conclude with specific political involvements of the LDS hierarchy and church in the 1990s. The first volume delineates the “evolution” of priest hood authority, the hierarchical church organization, and the Saints’ theocratic Kingdom of God, during Smith’s lifetime; the succession crisis following the founding prophet’s martyrdom in 1844; and the restructured leadership and organization of the largest single body of the fractured Nauvoo Mormon church, headed by Brigham Young, in 1847. The second volume selectively dis cusses related issues, namely “ecclesiastical, dynastic, theocratic, political, and economic,” most commonly by reviewing relevant pre-1844 events before elucidating subsequent developments up to the present.

The materials presented in these two volumes derive from an impressive thirty years of invaluable scholarly research and writing. Substantial portions of them have been published previously as journal articles. The formerly published portions of the second volume have not been revised significantly, while most of the previously published portions of the first volume are different, reflecting Quinn’s most recent thinking. In any case, it certainly is useful to have all of these materials gathered together in this form. This is, in my judgement, the great merit of this scholarly work.

These two volumes present a vast encyclopedia of topics and sources, primary and secondary, pertinent to the LDS hierarchy, organization, and more or less related issues. The narrative portion of these books consists of less than 700 of the more than 1,500 inclusive pages. The remaining pages, nearly one-half of these books, are composed of source citations, elaborate notes, a variety of lists, charts and the like, as well as relevant photographs of people and places, and a very helpful index to each volume. Some of this information probably is no longer readily accessible by way of the primary sources and documents; and much of it reflects Quinn’s acute, highly original analysis and seminal interpretation of exceptionally important scholarly matters, such as the 1844 succession crisis.

There are, as with any scholarly work of such enormous size and scope, some mistakes of fact, and more than ample room for serious differences of perspective, interpretation, and opinion about the facts and what they mean. I do not concur with what Quinn construes as the facts on a couple of topics that I know intimately, for instance, and I strongly disagree with his interpretation of these matters (such as his understanding of Alpheus Cutler) too. This is to be expected and it does not diminish seriously, in and of itself, from the immense value of this massive collection and presentation of information about the LDS hierarchy.

Selected portions of this encyclopedic work may be intelligible to a general readership. A great deal of it, however, presumes much more than basic literacy in Latter-day Saint studies, and many selections will be most useful primarily to research scholars with a very specialized knowledge and expertise in these particular areas. Portions of the narrative are very engaging, but some sections are not well written. It is difficult to imagine, however, that any future work on the LDS hierarchy or most of the topics and issues addressed could proceed competently without carefully considering what is contained in these volumes.

Whether or not these books systematically pursue a coherent argument (thesis of theory) about the LDS hierarchy raises a fundamentally different set of problems. Quinn claims little more than to present the evidence (data) and, thereby, to describe the development of the LDS hierarchy and organization. In other words, he pretends not to be engaged in much analysis (comparative or otherwise) or interpretative theorizing. This, of course, is not the case. Every supposed fact necessarily presumes some theoretical frame of reference whereby what is to be treated as the data is selected and defined as such. Furthermore, facts never merely speak for themselves: Any presentation of the facts necessarily presumes, even if only implicitly, some device or theory whereby the data are assembled and arranged in the form of a description. All descriptions also are interpretations, even if they are not very ambitious.

Indeed Quinn employs at least three theoretical devices in selecting the facts and presenting them. The most obvious (and therefore entirely taken for granted) one concerns what everyone who knows anything about the Latter-day Saints takes to be the “hierarchy” and what this entails organizationally. Another obvious one essentially is historical, involving the temporal sequence or chronological order of events (some of which are and some of which are not treated as significant) in the development of the LDS hierarchy. The third, more ambiguous device pertains to the largely implicit notion that certain other issues (such as internal organizational conflicts, kinship relationships, finances, violence, and partisan politics) directly relate in particular ways to de scribing the development of the LDS hierarchy.

All of these interpretative de vices are employed throughout, but to a greater or lesser extent in certain portions of the larger work. The first volume, much more than the second, systematically describes the emergence and development of the Mormon hierarchy from about the 1820s to the 1847 reorganization of the First Presidency. In the process, it also coherently explicates specific themes directly relevant to the LDS organization, such as the development of religious beliefs and practices, family and kinship relations, and secrecy, as well as internal and external political conflicts and violence. Unfortunately, Quinn unreflectively and uncritically employs an insider’s understanding of what organizational categories and units are and are not relevant for presentation. These conceptual categories depend on a very contemporary perspective, grounded in LDS belief, about what this hierarchical organization entails.

“History” thereby gets mixed with and informed by an implicitly LDS faith-based viewpoint. Besides resulting in an annoying presentism (a flaw shared by both volumes), there consequently is nothing particularly compelling about some of Quinn’s interpretative descriptions. For example, the “evolution” of various early Mormon beliefs and quorums might be interpreted with at least equal plausibility as revolutionary. Indeed, Gregory A. Prince, Having Authority: The Origins and Development of Priest hood during the Ministry of Joseph Smith (Independence, MO: Independence Press, 1993), advances such an interpretation. Similarly, the continuity Quinn finds in the nature of apostolic succession very easily could be described from the standpoint of the subsequent rationalization of ambiguous organizational principles and units involving a certain discontinuity. Thomas F. O’Dea’s The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1857) provides a highly relevant but largely ignored model for such an analysis and interpretation of the LDS hierarchy and organization.

The major issues and themes that Quinn selects for discussion in the second volume appear disjointed and they simply do not portray the LDS hierarchy’s twentieth-century development in an adequate, coherent, or intellectually satisfying manner. The chronological exposition of these developments is subordinated to the issues discussed substantially. This requires the reader to supply considerable knowledge of Latter-day Saint history as Quinn jumps from mention (sometimes all too briefly) of this event to another across two centuries in delineating conflict within organizational units, the importance of kin ship, finances, and external political relations. Since Quinn does not sup ply any explicit theory or general perspective for these mostly intriguing case studies, the particular issues chosen for attention may be understood as rather arbitrary. This also leaves him open to the criticism that the de scription is unbalanced on the whole.

It is inappropriate for any re viewer to tell Quinn how these mate rials should have been organized and presented more systematically. It is fair to say that without some more explicit justification for why certain issues were selected and how they are linked together, the results do not form a lucid, congruous scholarly work. Even so, these volumes contain a wealth of significant scholarly information. Quinn should be credited for this extremely consequential contribution to Mormon studies, as well as his sometimes brilliant, pioneering effort in opening up momentous, even if sensitive issues pertinent to the LDS hierarchy and organization for future discussion by scholars.

The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power and The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power. By D. Michael Quinn (Salt Lake City: Signature Books in as sociation with Smith Research Associates, 1994,1997).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue